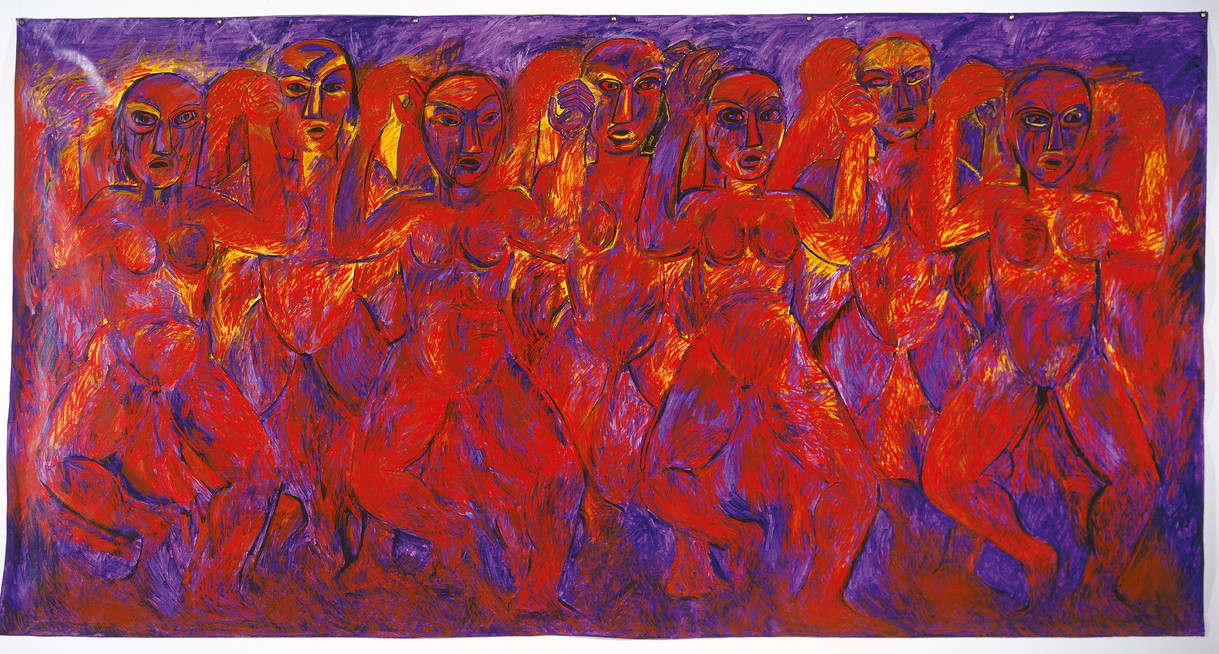

Ann Shelton The Scarlet Woman,

Valerian (Valeriana sp.) 2015. Pigment print

Representing Women: Ann Shelton’s Dark Matter

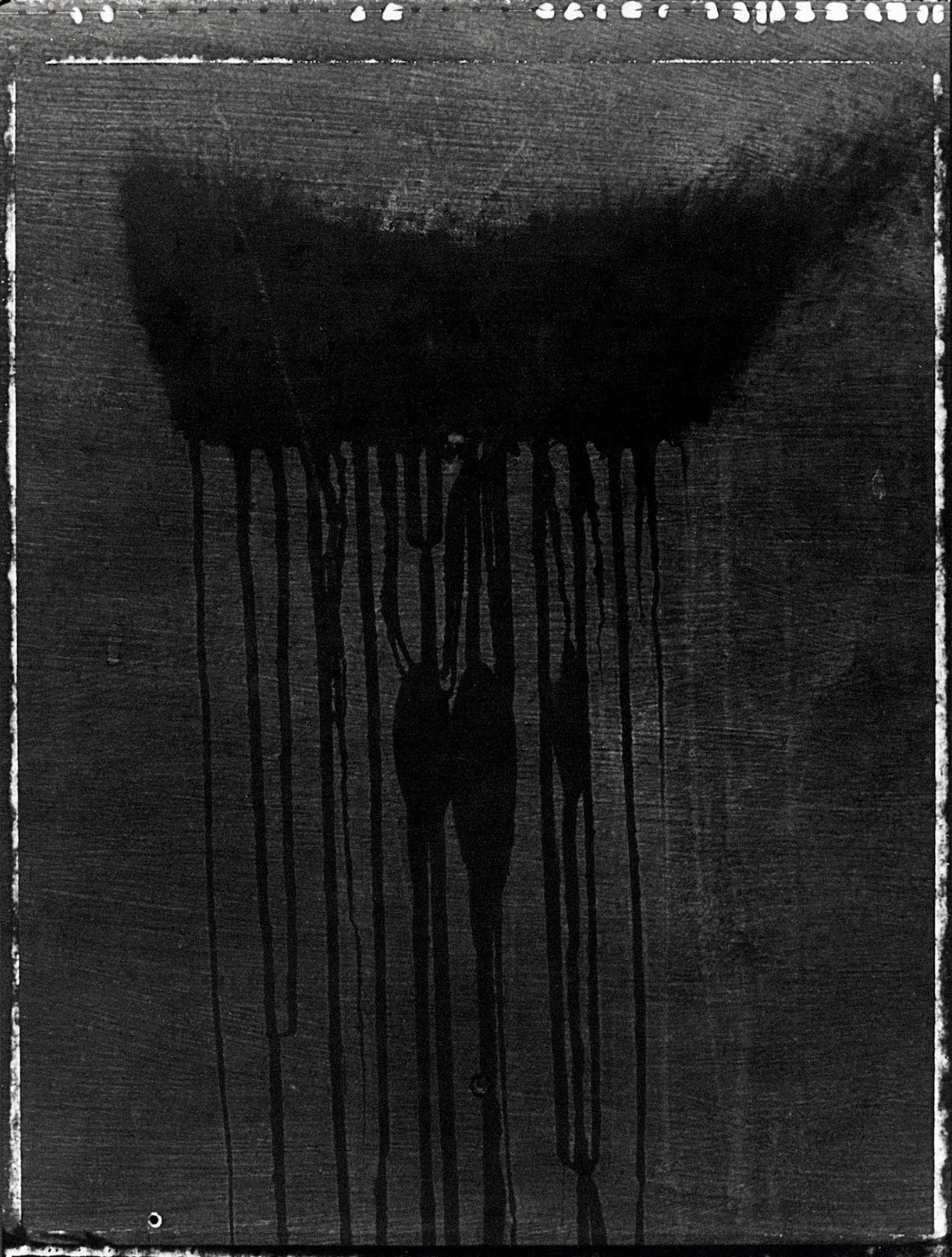

What is ‘dark matter’? For theoretical physicists it is matter that cannot be directly observed but whose existence is nevertheless scientifically calculable – productively present yet simultaneously invisible. In a similar vein, the everyday phrase ‘dark matter’ describes objects, conditions and situations that harbour unease or trauma. Trauma that is often concealed, repressed, or buried. Both definitions are active in Ann Shelton’s mid-career review exhibition Dark Matter, and they provide a rich point of entry into this compelling collection of her photographic work. These are photographs that bristle with intensity and refuse to let their subjects die a quiet archival death.

Curated by Zara Stanhope, Dark Matter foregrounds Shelton’s practice of researching marginalised members of society. Recalling the theoretical physicist’s definition of dark matter, she does this obliquely through what could be termed architectural and geographical surrogates, such as landscapes, historical sites, buildings, trees and plants. Shelton’s dark matter subjects are such that they cannot be directly observed; while it is true that photographing architectural and geographical sites is, in most instances, the only way the artist can represent her subjects, the formal techniques she deploys disrupt an easy or uncomplicated transposition from subject to site.

Through conceptual framing and formal strategies, Shelton toys with presence and absence as modes of representing female subjects. Her women are frequently historical and marginalised by their gender, by their sexuality, or as a result of their actions.

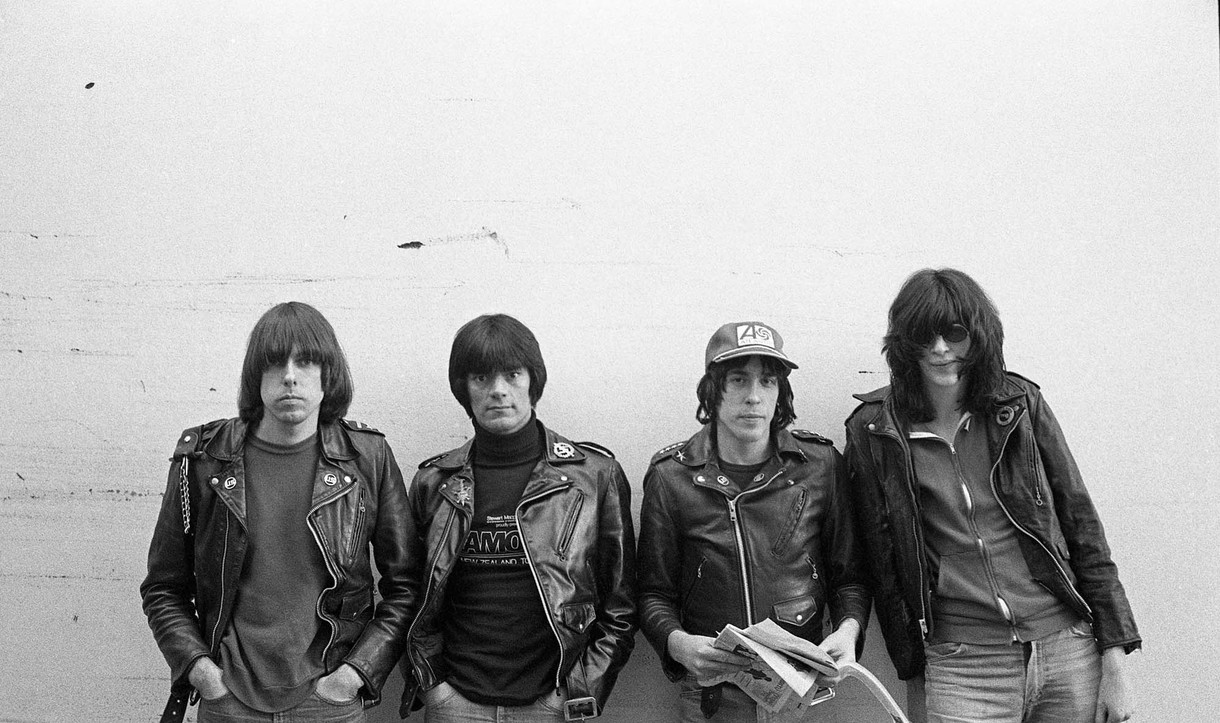

Perhaps the most important point to make concrete – one that has been hinted at by the language of surrogates, absence and presence – is that, with rare exceptions, people are largely absent from Shelton’s photographic practice. The notable exceptions to this are Redeye (1995–7) and my friends are electric (1997–2016). Redeye exemplifies the decision Shelton made in the late 1990s to turn the camera on the people and scenes that comprised her immediate world, rather than on the ‘other’.1 In the intervening decades portraits of Shelton’s friends in my friends are electric constitute the only human subjects photographed since this decision, although these portraits were only edited and published in 2016. In the comprehensive publication that accompanies the exhibition (also called Dark Matter), Shelton describes this decision to remove people (‘figuratively speaking’) as a ‘big shift.’2

The bracketed clause ‘figuratively speaking’ is important, as Shelton goes on to say: ‘They [people] are still very much present but through absence.’3 So who are they? Predominantly women who are marginalised by race, class, sexuality, and by the violence they have experienced. In some instances a convergence of these states has provoked women to themselves commit violent acts thereby further marginalising them as women (frequently the recipients of violence, not the perpetrators). And why these subjects? In Shelton’s words, ‘My projects are committed … to representing obscured histories or alienated narratives through absence.’4 This commitment – with particular focus on female subjects – is present in three bodies of photographic work: Public Places (2001–3), room room (2008) and jane says (2015–16). Dark matter is evident in these three series as both something that cannot be directly observed (absence/presence) and as trauma. Each series deploys a distinct photographic strategy to buttress the dynamic of absence/presence and to problematise the medium of photography, especially the claims of veracity made in its name.

By interrogating the erasure (or sensationalism) and ‘othering’ of these marginalised subjects, Shelton’s project meets key feminist objectives of ‘shifting, changing or revealing dominant understandings in order to challenge power relations and improve the material conditions for the lives of groups and individuals.’5 By problematising the representation of marginalised subjects through formal strategies, Shelton adheres to the conviction that ‘feminist discussions of representation must be continuously self-critical, but at the same time not abandon the task of working towards an ethical involvement with “others”.’6

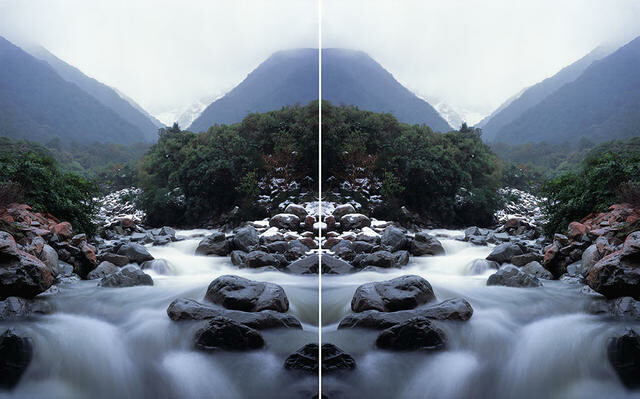

Ann Shelton Doublet (After Heavenly Creatures), Parker-Hulme Crime Scene Port Hills, Christchurch, New Zealand 2001. Diptych, C-type prints. From the series Public Places. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2004

In diametric opposition to its innocuous title, Public Places is a series of large C-type photographs heavy with dark matter. Drawn from biographical, fictional, and ficto-biographical sources (fiction, film), the subjects of Public Places include Janet Frame; Kerewin Holmes (the protagonist of Keri Hulme’s The Bone People); Aileen Wuornos; a class of disappeared Australian school girls; ‘baby farmer’ Minnie Dean; and Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme, who murdered Parker’s mother in Christchurch’s Port Hills in 1954.

Shelton photographed actual architectural or geographical sites pertaining to each of the women, be they imagined or real. To characterise Parker and Hulme, she photographed the leaf-strewn forest trail in the Port Hills where the two girls murdered Parker’s mother. The dilapidated, eyeless windows and doors of the Seacliff Asylum in North Otago characterise Janet Frame. But how do we know this by looking at large landscape photographs? Primarily through the labour of the lengthy titles Shelton gives to each work. The full title of the Parker-Hulme work is: Doublet (After Heavenly Creatures), Parker-Hulme crime scene, Port Hills, Christchurch, New Zealand. In this title we have an allusive word ‘Doublet’ that incorporates both ‘double’ and ‘doubt’, although I am not suggesting that Shelton is questioning whether or not the incident took place. But the word does ease the viewer into the event’s cinematic portrayal by Peter Jackson, only to deposit them into the historical and geographical specificity of the Port Hills.

Lengthy titles do not do all the labour, however. It is significant that each work in Public Places is not only a diptych, but a diptych that is doubled and reversed – a replication, a double, along a horizontal axis. Shelton demonstrates the impossibility of one truth-bearing image, and the corresponding idea that there is not (only) one story, or one version of events. Ostensibly displaced from representation, these marginalised female subjects are co-constituted with the architectural or geographical locations Shelton photographs, named (as in not forgotten) by the lengthy titles, and amplified by the formal strategy of a doubled and reversed diptych. These formal strategies create potential additional spaces to listen out, or search the archive for the backstories that doubtlessly contributed to the situations in which these women found themselves and acted.

From exterior landscapes, Shelton’s series room room moves indoors, specifically to the ‘private’ dwellings of clients housed in the Salvation Army’s now closed rehabilitation centre for drug and alcohol addiction on Rotoroa Island in Auckland’s Hauraki Gulf. Shelton photographs vacant rooms in the women’s Phoenix block that are dilapidated and worn by use and neglect. The narrow, stained mattresses and peeling wallpaper contrast with the pastel shades of the walls. Here too the viewer has arrived in the after-melt, in dark matter’s aftermath. Foregoing the diptych format of Public Places but retaining the strategy of reversing the image, Shelton amplifies the presence of the Phoenix block women with a fish eye effect that shunts the abject rooms into the viewer’s eye. Rather than presenting the expected concave depiction of an inmate under surveillance, Shelton forces the viewer to assume the role of the spied upon, a formal decision that perhaps attempts to return a measure of agency to the Phoenix women.

![Ann Shelton Pheonix block, room # unknown [yellow walls] 2008. C-type photograph](/media/cache/8c/a1/8ca19b55b282f681e2a25a7dc6b6aaa9.jpg)

Ann Shelton Pheonix block, room # unknown [yellow walls] 2008. C-type photograph

This intention of recuperating agency for marginalised women seems heightened in Shelton’s most recent body of work jane says. Each of the nine works from this series presented in Dark Matter depicts an elegant haute-flora tribute of flowers, weeds or herbs arranged and displayed in a distinctive vessel against a vivid monotone backdrop. As with Public Places the title and the ostensible subject matter of jane says can be deceptive. The floral tributes against bright backdrops are beautiful but they characterise the limited reproductive agency of women over their own bodies; each botanical entity has been used as part of a recipe or tincture for either an emmenagogue or abortifacient: they are plants that enabled women to control reproduction. Each tribute therefore represents the loss of esoteric or arcane knowledge, and subsequent co-optation of women’s reproductive control by pharmaceutical companies.

As with Public Places, the lengthy titles of jane says undertake a measure of the labour in decoding their apparently benign subjects. Each of the nine photographs has, in addition to a Latin taxonomical name, a comparative taxonomy of female ‘types’ whether historical (The Courtesan, Poroporo [Solanum sp.]), fictional (The Mermaid, Wormwood [Artemisia sp.]), moral-cultural (The Scarlet Women, Valerian [Valeriana sp.]) or diminutive-cultural (The Ingénue, Yarrow [Archillea sp.]). In jane says stereotypical types of women, haute-flora as abortifacients and the loss of (natural) reproductive agency converge powerfully. To further articulate the message, Shelton designed a large takeaway sheet titled the physical garden that incorporates an extensive anthology of excerpts on the abortive and emmenagogic properties of plants. In recognition of the historically oral mode of transmitting plant knowledge the physical garden’s paper archive is recited aloud amongst fresh flowers strewn before jane says. In this body of work Shelton instantiates a performative dimension to conceptually and formally activate the dynamic interplay of absence and presence that characterises her compelling representations of marginalised female subjects.

Images of women as commodified, sexualised objects in capitalist societies are ever present and difficult to avoid. By not photographing women (particularly in the three series that focus on women), Shelton is at once countering the objectification of women and highlighting the invisibility of (non-objectified) women. Shelton presents us with this impasse. Furthermore, the absence of women prompts the question: is it possible to represent women as full, non-sexualised, non-objectified subjects? What would such representations of women look like? In a photographic language of doubles and reversals that leaves space for change, Shelton shows us the dark matter of female lives limited by the violence of narrow stereotypes.