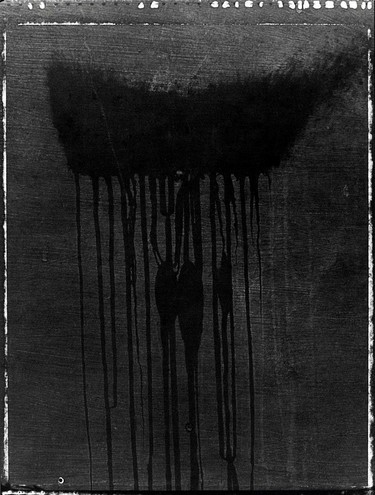

Fiona Pardington Moko 1997. Photograph. Gold-toned gelatin silver hand-print on fibre-based archival paper. Courtesy of the artist and Starkwhite, Auckland

The Camera as a Place of Potential

To Māori, the colour black represents Te Korekore – the realm of potential being, energy, the void, and nothingness. The notion of potential and the presence of women are what I see when I peek at Fiona Pardington’s 1997 work Moko. And I say peek deliberately, because I am quite mindful of this work – it is downright spooky. Moko is a photographic rendering of a seeping water stain upon the blackboard in Pardington’s studio, taken while she was the recipient of the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship in Dunedin in 1997.

‘It was just a random thing in a near empty Frances Hodgkins studio. What I saw immediately was a woman’s moko kawai, and I thought this is a tohu for me from women in the family.’1

But consider Pardington’s earlier work – family was her starting point, and then came a warp of lovers, mysticism, and a feminist form of eroticism that provided a responding critique of the male gaze. As she began to pack her work with the potential and opulence of dreams, her sense of responsibility to the politics of representation also unfolded. And then, in one particular case, came the indefinable. I mean, when is a water stain upon a blackboard not a water stain on a blackboard? When that stain is conceived by the artist as something else. For Pardington, the stain was understood as a sign, a point from which to pursue a particular pathway. From here, all bets for carrying the previous concerns forward were off, and Moko can be seen to be a transitional point, a pivot for the artist’s focus. It is from here Pardington initiates her desire to understand a Kāi Tahu world view and represent it within her work.

From this perspective, it is important to note that the work comes from a water stain, because water is a sacred element to Māori – a taonga left by the ancestors to provide and sustain life.

‘It’s like tears. I was thinking about the loss of land and the inter-tribal fighting, all the heavy stuff that went on. I was aware of what women went through and so for me too with the kind of issues I’d had trying to find my family it kind of all made sense.’

Now hold for a moment the idea that for Māori nothingness is relevant to every aspect of life; parallel to this is also the fact that nothingness as an idea holds considerable significance within twentieth-century Western art history. Conceptualism and minimalism expand and contract the notion of nothingness, from Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915), where the small canvas is hung across a corner of a given room, to the immense but intimate land-art works of James Turrell, which place the viewer in a roofless space where light and sky change colour and where they can contemplate everything and nothing without distraction. Nothingness is not empty but full of potential. Nothing, or the void, also holds important ground in photography: the chamber of the camera is where the light-sensitive material of film is protected. Light enters this chamber through the aperture and burns its unfixed image upon the exposed film. This poetic moment provides another relationship for Māori to explore in the world of art-making.

For Māori nothingness is everything. Nothingness within the Māori world view is within the many fields of Te Po – the void, the night, the place without light, but also the place where once light did enter and creation, or life, began. With this in mind the potency Pardington invested in the photographic moment saw two universes merge, and something of the European art world that so many urban Māori artists grew up in was met by something that led her towards her Kāi Tahu heritage, which had until then been quietly kept in the background.

‘For me it’s very much about what are the beautiful things you can construct out of the things that are shattered and broken. For me that wasn’t putting me off or too much of a downer, I just saw it as part of the journey and an acknowledgment that I was heading in the right direction.’