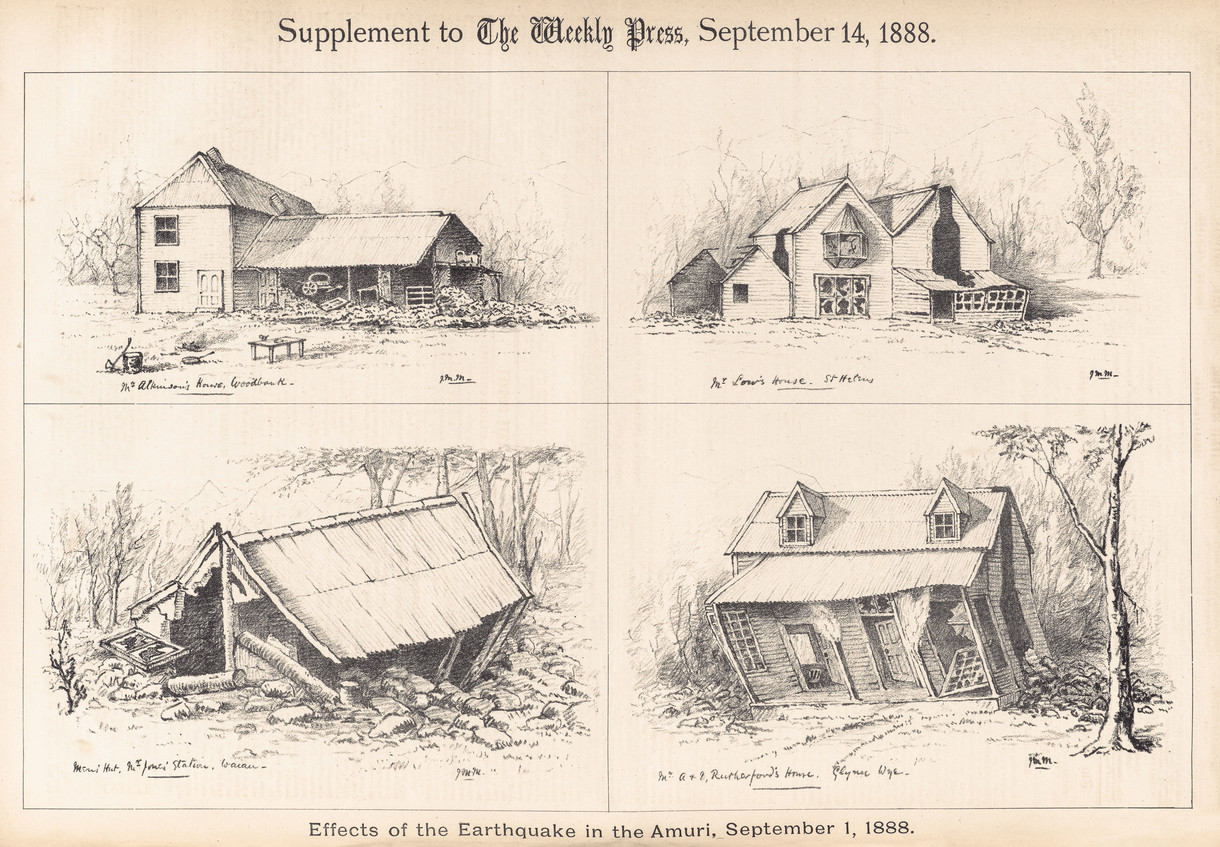

Holly Best Untitled 2015. Photograph

The Lines That Are Left

Of landscape itself as artefact and artifice; as the ground for the inscribing hand of culture and technology; as no clean slate.

— Joanna Paul1

The residential Red Zone is mostly green. After each house is demolished, contractors sweep up what is left, cover the section with a layer of soil and plant grass seed. Almost overnight, driveway, yard, porch, garage, shed and house become a little paddock; the border of plants and trees outlining it the only remaining sign that there was once a house there.

Daegan Wells Untitled (Extract from ‘Lodgings’, Residential Red Zone, 57 Banks Ave) 2015. Concrete, slate

This action has been repeated thousands of times, house by house, across the Red Zone, and has turned a large portion of east Christchurch into a de-urbanised, semi-wild green belt – an area that includes my old family home on New Brighton Road. The nature of the Red Zone can only be grasped by a walk through it. Broken streets and signs mark empty suburban blocks, disused power poles lean in wonky directions, flocks of birds (korimako, bellbird, silvereye, Canada geese) noisily erupt from trees and riverbanks. On foot, it goes on for hours. From the Avon Loop and south Richmond near the city, along the banks of the Ōtākaro Avon, to Bexley and the wetlands on the shore of the Ihutai Avon/Heathcote Estuary, it is a quasi-urban/natural environment unlike much else.

Nobody yet seems to know what will happen with the Red Zone. Nature reserves, urban farms and water parks have been suggested by community groups. Some residents already see the area as a park, taking their dogs for walks along the bumpy, overgrown footpaths. Keen foragers make trips into it in search of fruit trees and vegetable patches. Other residents stay away.

And of course, local artists have found themselves drawn to the Red Zone and making artwork in response to it. Here, I want to look at two of them, Holly Best and Daegan Wells, who have been making artwork within the Red Zone for the past few years.

Holly Best Untitled 2013. Photograph

Best is a photographer and Wells works with found materials and installations, typically in site-specific locations. Although they use very different methods, there are links between Best’s and Wells’s practice beyond the Red Zone environment they both, at times, work within. Their artwork uncovers traces of culture and memory, and they touch on themes of relocation, absence and continuity. Subdued observation and collection inform their practices; their subject is given room to speak for itself.

These notions echo Walter Benjamin’s idea of history as emerging from flashes of memory and everyday objects, an ‘endless series of facts congealed in the form of things.’2 Benjamin’s opus, Das Passagen-Werk or The Arcades Project, a massive, incomplete collection of writings on Paris’s shopping arcades, was obsessively worked on for decades, seemingly without hope of forming an end. He saw in the arcades of Paris dramatic (Marxist) themes on the nineteenth century’s economic and technological changes. But these ideas are only gestured at in The Arcades Project. He is more content to dwell in fragments and glimpses, leaving behind a work as sprawling and labyrinthine as Paris itself.

Within the Red Zone, Wells has been steadily drawn to the former home and studio of artist W.A. Sutton, one of the few houses that still stands in the area. The Sutton house was a central point for Christchurch’s arts community from the early sixties. Wells came across the house in early 2014, and realised its significance, by chance, when he found the Historic Places Trust plaque on the ivy-covered, cinder block wall outside. Since then, he has visited regularly, taking an approach similar to Benjamin’s. Wells takes photographs of objects such as garden pots, writes notes and collects plant cuttings to mush into pigments; he stays within the garden, and does not remove any objects from the section. More recently, he has done research in the Gallery’s Sutton archive, finding further, overlooked pieces related to the arts community around the Sutton house. These kinds of sources lie outside established narratives and their everydayness often says more about the people who moved through the places he documents.

For the past few years Best has also been a witness to the Red Zone. Walks through the area are frequent, on the way taking photographs and foraging for fruit; often with her daughter Claudia alongside in a pram. In this way, the area is not an exceptional environment, but an everyday one. To Best, what could be seen as disorientating or unnervingly dystopian in the landscape is not unusual. In a series published in Enjoy Public Art Gallery’s journal,3 she studies trees in the Red Zone. Her approach is playful, sometimes with slight abstraction; trees awkwardly wrapped in a tarpaulin or DANGER DO NOT ENTER tape, thriving triffidesque weeds, contorted hedges unsure of where to grow. Because the Red Zone is a normal part of Best’s life, as a subject it fits with her photographs taken at home, like those of a song thrush that regularly visits to be fed or her family in the garden. These photographs are a kind of reimagining of domesticity; scenes and memories from the homes that have since moved on from the Red Zone, leaving only fence lines in the short grass.

Holly Best Untitled 2013. Photograph

The Sutton house was one of several residential locations Wells initially worked from, a part of a larger project titled Lodgings.4 Several installations emerged from Lodgings; a joint exhibition Kissing the Wall with Michael Lee at North Projects artist-run space, and installations in Wells’s studio and the Red Zone itself. These installations emphasise absence, and advance a critique around the upheaval of residents from their former homes. By collecting found objects (and afterwards returning them to where they came from), Wells acts as curator, archivist and a kind of caretaker; carefully selecting each object and placing it in the empty space of a gallery, studio or house. These objects are sensitive material, and this could explain why Wells stays within the garden of the Sutton house, and does not take objects from it. He notes that in the time he has been visiting, the front gate and the guttering have been stolen, and the doors screwed shut.

The remains of fence lines around each section in the Red Zone are noted by Best. Left-behind trees are often markers of these lines, and in Best’s words ‘they suit a corner or make a line; construct fine barricades.’5 They dot the landscape, solo or in clumps, with no sense of endemic normality; cypress, tī kōuka cabbage tree and magnolia settle as odd neighbours. The area has become a sanctuary for the gardening whims of former residents. Along with these fence lines, in the time Best has spent in the Red Zone, new fences and roadblocks (albeit easy to climb over or walk around) have been erected around it. Best sees these lines as traces of the segmentation that continues to form and re-form Christchurch city life. The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman believes that one main feature that defines all cities over time is that they are spaces where strangers stay and move close to one another.6 That this is despite a common insecurity of strangers. Best’s photographs are a reminder that, despite the gradual regrowth of nature in the Red Zone and the upswell of community-led projects in Christchurch over the past few years, these fence lines are deeply ingrained.

Daegan Wells Untitled (Extract from ‘Private

Lodgings’ William Sutton’s Garden) 2016.

Silver gelatin print. Jonathan Smart Gallery

Before writing this, I visited the street where my family home used to be. My dad came along – he wanted to see how the trees he planted were doing. We climbed over the fence and walked up the remains of our old driveway. Standing out in the open, where our yard used to be, he gave me a rundown of each tree and when he had planted it: paperbark maple, tarata lemonwood, houhere lacebark (his pride and joy). I told him about the places to forage nearby. Our neighbour’s walnut tree, a giant pear tree a few sections north, scattered apple trees, a feijoa and lime tree right next to each other further north-east. How, quite often, I would see kārearea, New Zealand falcon, flying overhead. When my parents left this house, they took from their garden whatever they could dig up and replant at the new one. His trees had to stay.

Why artists such as Holly Best and Daegan Wells are drawn to the Red Zone is difficult to answer satisfactorily. Put bluntly, the Red Zone is considered because it is here in Christchurch, there is a lot of it, and it is strange. Historically, New Zealand has been continually interpreted through depictions of place: Pākehā’s uprooting of Māori from their land, the isolation of rural life faced by vast landscapes on every horizon. But the Red Zone is something else. It is an urban environment taken apart, made bare. In the Red Zone, Best and Wells observe and find traces of the suburban, habitual ways of life that remain in this cleared, post-urban landscape. Their artwork suggests the streets, houses and rooms we move between every day; the new places we find our feet.