Laurence Aberhart

The Music Years

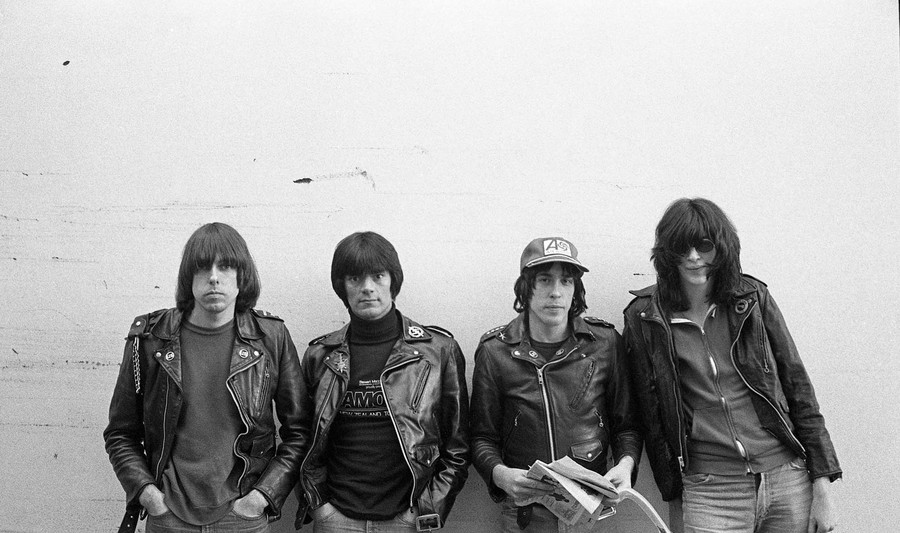

Laurence Aberhart Ramones, Christchurch, 24 July 1980. Photograph. Collection of the artist

New Zealand artist Laurence Aberhart is internationally regarded for his photographs of unpeopled landscapes and interiors. He photographs places redolent with the weight of time, which he captures with his century-old large-format camera and careful framing. But he’s always taken more spontaneous photographs of people too, particularly in the years he lived in Christchurch and Lyttelton (1975–83) when he photographed his young family, his friends and occasionally groups of strangers. ‘If I lived in a city again,’ he says, ‘I would photograph people. One of the issues is that I even find it difficult to ask people whether I can photograph a building, so to ask to photograph them – I’m very reticent. I also know that after a number of minutes of waiting for me to set cameras up and take exposure readings and so on, people can get rather annoyed. So it’s not a conscious thing, it’s more just an accident of the way I photograph.’

In the late 1970s, Aberhart took on a number of commissions to photograph rock musicians playing in Christchurch for Auckland-based music magazines Rip It Up and Extra. He’d met their editor Murray Cammick a few years earlier at Snaps Gallery in Auckland. Cammick had studied photography at Elam under Tom Hutchins and John B. Turner, and was encouraged by them to take social documentary photos for the student magazine Craccum. He began a series of gritty photographs of music gigs in Auckland and documented the V8 car culture of Queen Street. When he launched Rip It Up with his friend Alastair Dougal in 1977, Cammick intended that the magazine would also provide a forum for contemporary photography, including his own. But the need to sell advertising meant that it didn’t quite work out like that: ‘We never had much space, and the photos often ended up at postage stamp size. The first issue had a double-page spread of the Commodores, and that was my original vision for the magazine.’

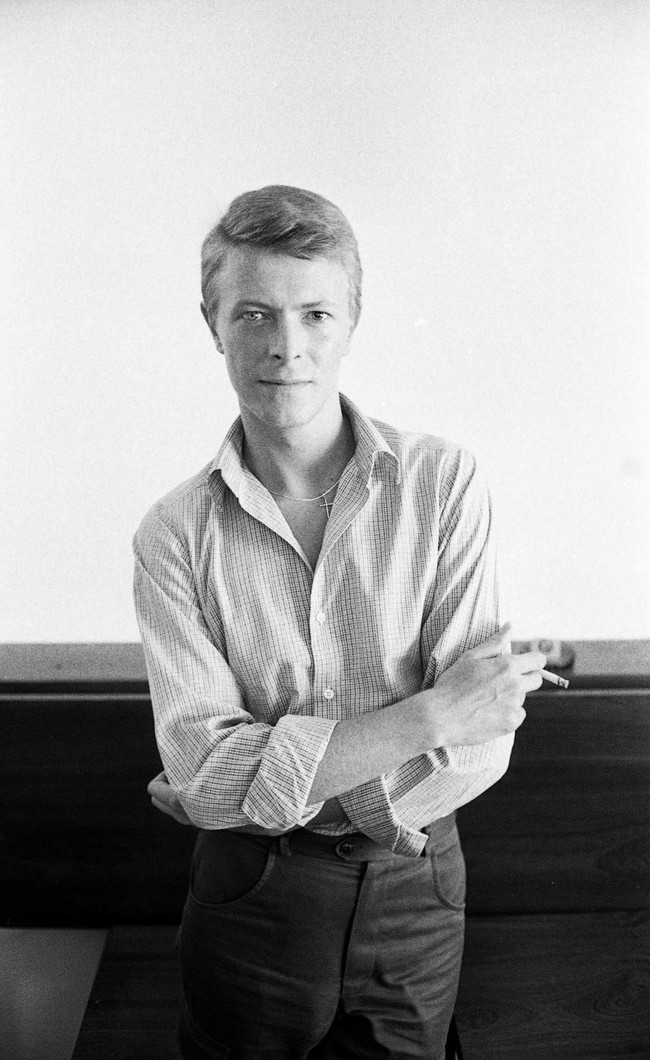

With Rip It Up, says Cammick, he and Dougal wanted a ‘back-to-basics approach to music. No art rock or country music!’ They were particularly interested in soul, but covered the emerging punk and new wave scenes. ‘When you start a magazine you think you’re going to be telling people what they should like, but you end up reflecting their taste.’ He first used Aberhart in late November 1978 for a photograph of David Bowie in his Christchurch hotel room. ‘We were thrilled to have Laurence taking photos for us … It was pretty obvious he was a great photographer, full stop.’

Laurence Aberhart David Bowie, ‘Heroes Tour’, Christchurch, 28 November 1978. Photograph. Collection of the artist

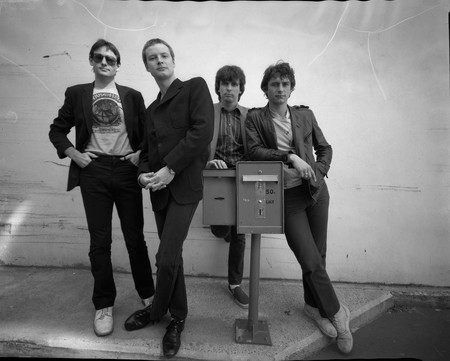

Laurence Aberhart XTC, Christchurch, 12 September 1980. Photograph. Collection of the artist

Cammick launched Extra in 1980 in an attempt to give more space to photographers. It ran for two issues, and featured Aberhart’s images of XTC and the Ramones, taken in the car park at the back of Noah’s Hotel, Christchurch, in July and September of that year. While the homegrown music scene was expanding rapidly, New Zealand was also becoming established as a destination for international concert tours. ‘At that point’, says Aberhart, ‘rock acts would often fly in to Christchurch and out from Auckland, and it was easier to do the media stuff in Christchurch. Murray couldn’t afford to fly down, so he’d ring me up. Free tickets weren’t involved.’

Aberhart photographed the Ramones and Bowie using his 35mm Leica camera, ‘for expedience’. For XTC, however, he used the vintage 8x10 camera that he’d bought from American photographer Larence Shustak. The images he produced belong, I think, in the pantheon of great music photographs, in which the emotional vulnerability of the performers is exposed along with their showmanship. And though the faces are in some cases household names, the photographs are first and foremost Aberharts, full of the same dense, melancholy time as his landscape photographs. Cammick comments: ‘He pulled it off with XTC and the Ramones. XTC were a band who didn’t like their photos being taken, and the Ramones were sick of it. And somehow he managed to take photos of Bowie without Bowie controlling the image. I don’t know how he did that.’