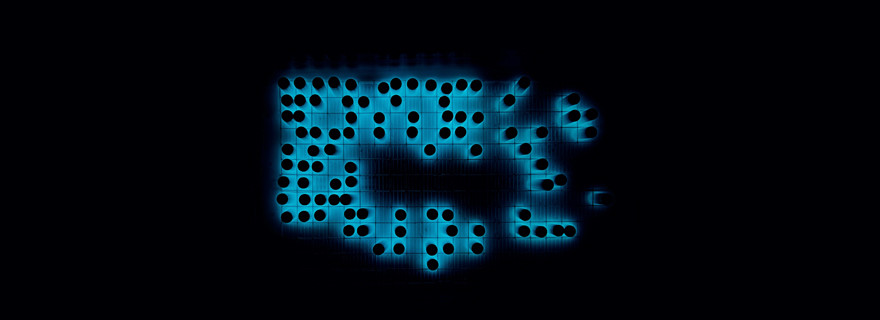

Taryn Simon Nuclear Waste Encapsulation and Storage Facility, Cherenkov Radiation, Hanford Site, U.S. Department of Energy, Southeastern Washington State 2005–7. Chromogenic colour print. © 2007/10 Taryn Simon. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery / Steidl

Taryn Simon's known unknowns

In 2003, the American photographer Taryn Simon embarked upon a four-year heart-of-darkness journey. In response to paranoid rumours of WMDs and secret sites in Iraq, she turned her gaze to places and things hidden within her own country.

The work is meant to be disorienting. It was produced during a disorienting time in my history as an American. There is an element of exploration—of discovering a new American landscape—politically, ethically, and religiously.1

The resulting exhibition – An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar – is an idiosyncratic guide to the American mindset, whose subjects traverse the realms of science, government, medicine, entertainment, nature, security,and religion. Among other things, the show takes in glowing capsules in an underwater nuclear-waste storage facility, a Braille edition of Playboy, a retarded inbred tiger, a teenage corpse rotting in a forensic research facility, the Death Star and a Scientology screening room. Shot with a large-format view camera, Simon's images range from ethereal to foreboding, from deadpan to luscious. Each is accompanied by a text that provides often chilling background information on what is shown.

Walking through the show, one is surprised-but never so surprised. We know rape victims get DNA tested, so it's not implausible that somewhere there is a backlog of kits awaiting analysis. National borders are protected by customs agents and patrols – it would only be scandalous if they weren't. And this won't be the first time we've heard of the KKK, cryonics, serpent handlers, government bunkers, and black ops. But while we know all these things, we don't expect to be confronted with them en masse. Simon's subjects are mostly the half-secrets that people exile to the backs of their minds to maintain their collective sense of security as they live their lives and go about their business. As one commentator put it, ‘What's most strongly conveyed by these photographs is how conscientious we can be about what we don't want to be conscious of.'2 Slavoj Zizek said something similar when he observed that Americans saw 9/11 as unimaginable when Hollywood had been imagining it for years.

It's hard to look at the Index without speculating on the research and negotiation that would have attended the creation of each image. What did Simon have to say in order to get access? How much resistance did she face? How secretive was she about her intentions? If this is what she can show, what is it that she can't show? One imagines that many of the bureaucrats and technocrats who permitted her access were understandably proud of their well-oiled facilities, like that executioner in Franz Kafka's story In the Penal Colony who finally demonstrated his machine on himself. However, Simon acknowledges resistance in one work. This text-only piece excerpts a 'no letter' from Disney which argues that 'the magical spell cast on guests who visit our theme parks is particularly important to protect and helps to provide them with an important fantasy they can escape to.' It is odd to think that one can photograph nuclear-submarine work stations, the mint, the CIA, government marijuana crops, and death-row exercise cages, but backstage at Disneyland is off-limits. Simon suggests that the entertainment industry may be more fastidious than the military in maintaining appearances.

For me, one image offers a telling key to Simon's inquiry into secrecy. Hymenoplasty, Cosmetic Surgery, P.A., Fort Lauderdale, Florida shows an operating theatre in which a young woman, spread-eagled in stirrups, awaits an operation to restore her hymen 'to adhere to cultural and familial expectations regarding her virginity and marriage'. The image is conflicted. On the one hand, the woman is obscenely displayed; on the other, her face is hidden and her sex modestly veiled. Perversely, the image exposes the existence of a dishonest procedure but protects the woman's identity, making us complicit with her subterfuge. In specifying that the woman is 'of Palestinian descent', Simon's text introduces a twist. Through its support of Israel, America may be implicated in the deceitful oppression of Palestinians, but here, in the 'free world', this young Palestinian-American woman's own lie can be enabled. Is restoring her 'innocence' resisting misogynist cultural expectations or buying into them?

It's complex. America is complex.

As much as Simon reflects on America, she also reflects on photography. For someone who cut her teeth as a photojournalist, she is surprisingly skeptical of photography's claims to truth and attentive to its limitations. Her previous series, The Innocents (2003), presented portraits of persons who had been wrongfully convicted, often on the basis of photographic evidence. The Index also emphasises misrecognition. Simon compares her approach to that of exploration-period artists who made seductive images of locations and specimens only to supplement them with the driest of descriptions. Simon's texts emphasise what her spectacular images don't or can't say. Viewers experience a double take, only recognising the implications of what they have seen after they have read her text. Simon says, 'the image is meant to float away into abstraction and multiple truths and fantasy, then the text functions as this cruel anchor that nails it to the ground.'3

At first glance, it is easy to see the Index simply as a documentary project, but it is more than merely evidential. Simon's images are highly crafted, contrived, themselves duplicitous: she famously rearranged seized contraband to recall a classic Dutch still-life and chose a particular group of glowing nuclear-waste capsules because their disposition suggested a map of America. Rhetorical installation is also crucial to her plan. Simon insists on laboratory-white gallery walls and even, regular spacing of her images. And she runs her texts small, as if they were literally 'the fine print'. While the show appears sedate and systematic, the works—the registers they operate in and their implications—are so heterodox that they generate a burgeoning sense of disorder and dislocation. For all its encyclopaedic breadth, the paradox-fuelled Index refuses to join the dots. While it furnishes building blocks for a conspiracy theory, it pulls back from an overarching explanation. In doing so, it exemplifies, engages, critiques, and inverts Bush-period paranoia. The prospect of an American axis of evil constantly appears and evaporates under our gaze.

Robert Leonard is director of the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane