The Devil’s Blind Spot

Recent Strategies in New Zealand Photography

Jordana Bragg What do you fight for? 2016. Archival pigment print. Collection of the artist

Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery has a long-standing tradition of curating exhibitions of emerging and early-career artists. We do this in order to contribute to the ecology of the local art world, as well as because – quite straightforwardly – we’re interested in the practices of artists at all stages of their careers, and would like to bring the work of outstanding younger artists to wider public attention. The Devil’s Blind Spot is the latest in this ongoing series, but unlike earlier exhibitions, it’s concerned with a single medium – photography.

Why concentrate on photography in an exhibition of up-and-coming artists? Two reasons. Firstly, because photographic practice has arguably never been stronger in New Zealand; the diversity of approaches taken by the various regional art schools is producing a broad spectrum of critically-engaged photography graduates, who are building on strong local and international photographic histories. And secondly, because photography is the pre-eminent visual medium of our time. We’re bombarded by images, saturated with gifs and jpgs. With the rapid national take-up of smartphones and sharing technologies, many people have become not only photographers but also publishers and distributors of the photographic image. I wanted to consider how a group of New Zealand artists born in the 1980s and 1990s, who have come of age with the digital image, are using a range of strategies to make photographic art in the digital era.

Although it doesn’t attempt to be a comprehensive survey, The Devil’s Blind Spot brings together a wide range of contemporary photographic practices. At one end of the spectrum are artists who use deliberately anachronistic technologies, such as large-format view cameras and analogue film. Their images may be hand-printed in a darkroom, or scanned and delivered as digital files. At the other end are artists who work with computer codes and data, and whose photographic practices might involve online distribution and interaction. There are artists who make photobooks and those who produce cameraless photographs; artists who incorporate photographs into mixed-media installations or who are concerned with the creative possibilities of photographic ‘failure’; artists who explore aspects of personal or cultural identity from an insider’s perspective; and artists who are concerned with the visibility of photography’s own histories, as well as its relationship to other visual disciplines. Each represents a different kind of engagement with the contemporary, offering a distinctive critical reflection on the condition of culture at the present moment.

Every artist is represented by a new or recent body of work, and we’ve also commissioned accompanying texts on each artist’s work by peer writers, which appear on the following pages. Mirroring the approach taken in the exhibition, which considers the diversity of contemporary photographic practice as a strength, each piece of writing has found its own form – an interview, a parallel text, an exploration of ideas, the intimate observations of a friend or the close reading of a fellow artist.

The Devil’s Blind Spot is a title borrowed from the German writer Alexander Kluge. Subtitled ‘Tales from the new century’, Kluge’s book of short, acerbic ‘semi-documentary stories’ acknowledges the pull of the past while anticipating the great turbulence of our future, and hovers – much like photography – between fact and fiction. In contrast to the ‘decisive moment’ of photography, the notion of the devil’s blind spot gestures towards an indeterminate, hard-to-see period when history takes a new turn – a subtle course change that occurs while ‘the devil’ has his eye somewhere else. The shift in direction being gestured to in this exhibition is the result of the development of digital technologies and the consequent explosion of vernacular photography. Rather than a schism with the past it simply implies a renewed form of connection.

Digital technologies have long since refuted whatever claims of ‘truth’ photography once had as a document of the real (and have also helped us to see that photographic reality was always a construction). But it is not so much that reality is vanishing, as that a new form of reality is emerging that acknowledges the subjectivities of its actors. A photograph is not just an aid to vision but also a means of representation, both visual and political. What is excluded from the picture has always been as significant as what is included. Like other art forms, photography provides the viewer with a way of seeing – a distinctive perspective on the contemporary moment. What a photograph pictures is always past, but in its unique ability to isolate and preserve a moment in time for future viewers, it brings that past into a continuous dialogue with the present.

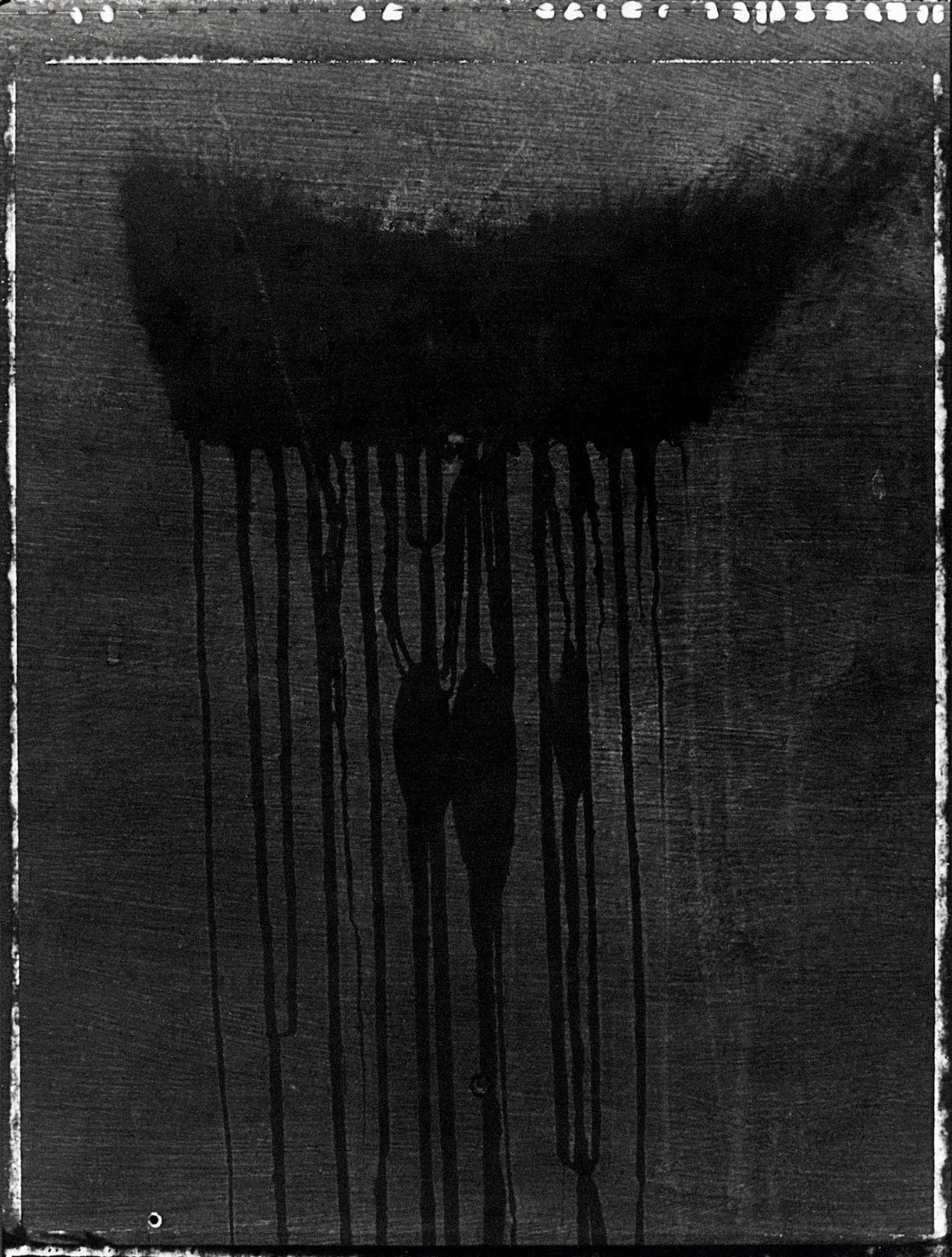

Andrew Beck Red Cutting through Black 2016. Acrylic, enamel, silver gelatin print, conservation glass in artist frame. Courtesy of Hamish Mckay Gallery, Wellington

Andrew Beck

Andrew Beck’s latest body of work is simultaneously regressive and progressive. Regressive, in that he has adopted the antiquated process of cameraless photography; progressive, in that he does so to accentuate and resist the dissolution that comes in the wake of an age in which instant gratification and a saturation of digital images reigns. He channels the past in order to make an art that is entirely grounded in the present.

Cameraless images directly transmute an object’s presence into an abstract representation. Working from the extreme end of the photographic spectrum, Beck circumvents the effects of modern, transitory visual media with striking works that act not only as photographs but also as substantial objects in themselves, sometimes manifesting even in sculptural forms. His recent works provide testament to the flexibility of photographs – their ability to speak not only of what is being represented but also of their method of production, in which moments in time are fragmented and frozen on a material surface.

A deceptive sense of three-dimensional space is generated on a flat surface, an impressively nuanced feat when working with the limited process of photograms, which fix the shadowed outline of objects layered on a surface. Also brought to our awareness is a fourth non-spatial dimension – time. As temporal and material worlds collide, the introduction of a circular motif reminds us that the time being represented here as discrete, split into separate images, is still perceived by our senses as part of a continuous cycle of events.

By destabilising the un-manipulated reflection of the world in the photographic image, Beck uses old techniques to a new effect and plays with the viewer’s perception. He presents us with a fresh visual system of abstract geometries, while simultaneously taking cues from early twentieth-century Bauhaus and Soviet artists. The reiterated geometric forms act as symbols of the revelatory force of the photographic medium and its unique ability to capture fractured segments of time in space. Beck reduces his art to the purest elements available to the eye – an act of resistance in a world overwhelmed by visual stimulation.

Ultimately, the corporeal nature of Beck’s photographic art provides a refreshing counter-experience to the one we are most familiar with today – the disconnect provided by a screen placed between viewer and image, a symptom of the digital age and its obsession with immateriality.

Nina Dyer is a Wellington-based art writer and student of art history and philosophy, currently studying under art historian and curator Geoffrey Batchen

Holly Best Nor’west Disappointment 2016. Pigment print on Hahnemühle photo rag. Collection of the artist

Holly Best

Holly Best and I have been friends for almost ten years now, after meeting at art school where we both studied photography. Recently I found a letter Holly wrote to me a year or so ago, folded in half and shoved into a novel I’m yet to finish. In it, she asks questions of herself and her photographs: How do black and white images of her daughter fit with those she’s taken in colour of friends, lovers and landscapes? Can she avoid being typecast as an earthquake photographer, or as a mother who photographs her child? How can she justify being (occasionally) more interested in colours, lines and shadows than the subjects she makes abstract? Now that I’m writing about her photographs in an attempt to define or at least consider what they are about, I’m faced with a related problem: are words like mine even helpful when trying to understand Holly’s work?

It’s easy to fall into photography’s indexical trap: the myth that these images truthfully represent the world around us. So often I find myself looking through rather than at photographs – discussing not the artwork itself, but the people, things or places they depict in the ‘real world’. But as countless writers before me have already discovered, it’s impossible for photographs to tell the whole story of their subjects – and to define Holly’s work by what it shows us misses the point. For as she said to me last week, her photographs are more like intuitive responses than calculated equations. And while they may be related to place, motherhood, friendship, or love, these things are not why she takes photographs and not what she goes looking for. As a writer – someone who relies on words to convey meaning – this is challenging and a little frustrating. Because words can’t easily explain why Holly’s photographs stick with their viewers; why people remember certain ones without seeing them for years.

For me, however, the impossibility of explaining what Holly’s photographs are all about is exactly what makes them magical, because artworks are fundamentally different to words. It fascinates me that if her photographs were paintings (the medium which I think Holly is most influenced by) I might not even be having this internal wrestling-match. And by focusing on what we see in her photographs as opposed to how we experience them – what our instinctive reaction is – I think we’re losing out. It’s telling that in this new work, Holly has presented a conceptual idea that speaks about photography and her experience of being a photographer above all else. Choosing to interrogate and in fact eschew photography in a context where it would seem more appropriate to embrace it, she’s avoided taking the obvious path. As she’s observed, having a child has changed the way she looks at things; in that letter, she spoke of her daughter’s ‘focus and selections, such intensity and exact emotional response.’ When looking at Holly’s work, I think we could all do well to emulate such a reaction.

Alice Tappenden is a Wellington-based writer, who is particularly interested in contemporary photographic practice.

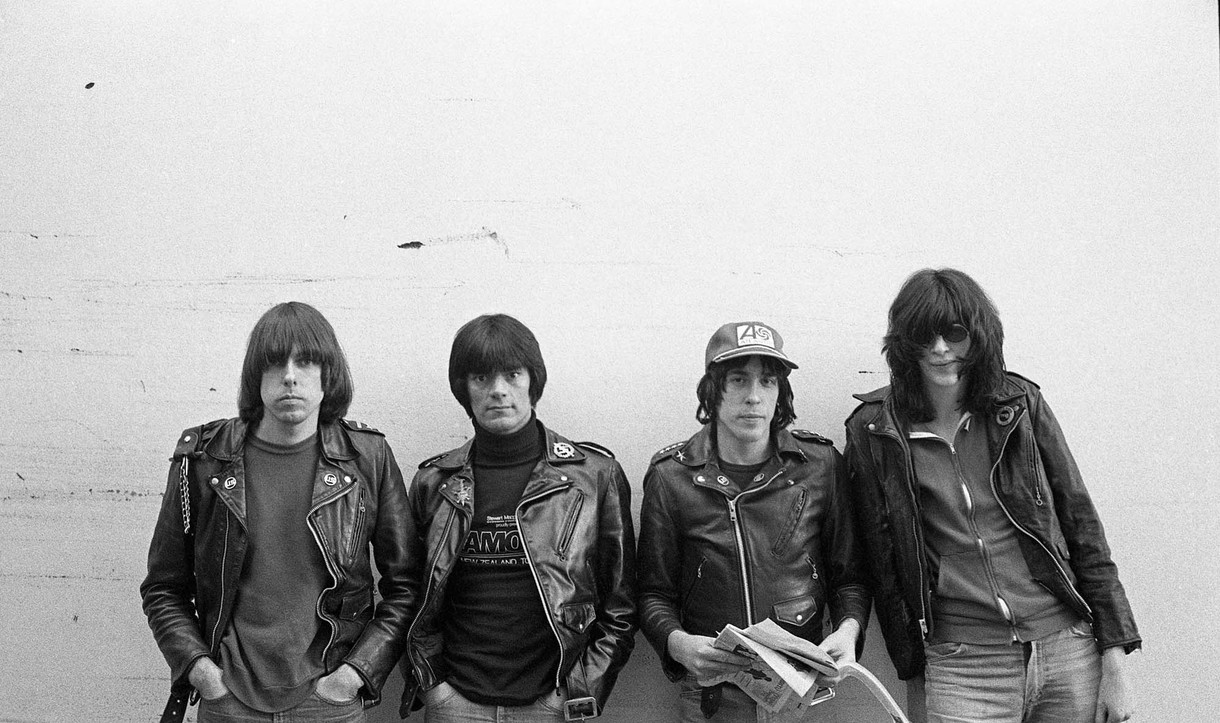

Jordana Bragg What do you fight for? 2016. Archival pigment print. Collection of the artist

Jordana Bragg

Jordana Bragg’s ten part photographic series Days Since and Again (So Soon) (2016) complicates typical public interactions with androgynous bodies and those who identify as gender non-binary. Bragg uses the camera for the purposes of self-portraiture and actualisation; displaying their own body, on their own terms, both concealing and rejecting the social conventions and anatomical traits of the biologically female body.

The camera has an interesting relationship to performance art practice; it’s commonly discussed as a device for the documentation of fleeting moments. In self-portraiture, however, the camera is set up solely to capture one specifically composed moment. In this way Days Since and Again (So Soon) is both documentation and traditional self-portraiture, as evidenced by the precise compositional decisions and stagnant body positioning, in combination with ‘everyday’ elements and an understanding that Bragg’s performance-based oeuvre is most often captured in moving image.

Each item of clothing worn by the artist in these photographs is unisex: regularly worn in casual settings and in a contemporary context, does not connote direct associations with any one way of identifying or being identified. Bragg’s clothing choices in many of these images, a light blue denim jacket, black jeans and black Dr Martens, adhere to a uniform of sorts. The everyday nature of their attire in the series in combination with Bragg’s short and partially shaved haircut, makes it apparent that this is the artist’s ‘natural’ expression of themselves, not performed specifically for the camera.

The images explore a variety of urban outdoor environments displaying moments where Bragg elongates their body to expose their concave bare stomach, ribs and bound breasts. The act of breast binding is practiced for many reasons by many different people, but in the LGBTQ+ community it is practiced for reasons associated with gender, for example to appear less-feminine or to suppress gender dysmorphia. Each image is documentation of self-narrative surrounding gender identity and the way in which the body can be presented in the state that is intrinsic and comfortable, but not necessarily gender normative. Similarly, the images taken indoors present the artist in various states of undress; exposing their bare back, unshaven legs, stomach, tattoos, unzipped pants and underwear. The domestic spaces where the artist has selected to take the images, seem to be spaces where they feel safe enough to reveal aspects of their person that are largely considered private.

By making this series in the year following the completion of Bragg’s fine arts degree, the disparity between the urban and domestic (and the artist’s body in relation to each), addresses a lack of security that is a consequence of abandoning the studio, which once offered safety. Exhibiting a level of vulnerability by displaying an intimate perspective, the audience is provoked to humanise and feel a sense of empathy with a commonly objectified, misunderstood and under-represented subject.

Bragg’s use of photographic self-portraiture has allowed for an assertion of control over how an audience may visually communicate with their body. In public contexts many individuals who visually challenge the aesthetic stereotypes of gender binary are often looked at and spoken to in a non-consensual manner – stared at and both verbally and physically harassed. Throughout this series the viewer’s gaze is coerced into a conversation that the artist has initiated. The dialogue created by a marginalised body for a public audience allows for a greater understanding between the two parties – allowing someone to show how they view themselves and in turn how they would like to be viewed.

Dilohana Lekamge is a Wellington-based visual artist whose practice consists of live-performance and performance-based video works.

Conor Clarke Twin Peaks, Berlin 2014. C-print. Collection of the artist. Courtesy of Two Rooms, Auckland

Conor Clarke

The day was overcast, the sky a tight-fitting lid. Drizzle jewelled our beards. We stood studying a row of barren mountains that scraped against the cloud. They were all unnamed and unclimbed. The potential for first ascents was thrilling.

‘There’s a good line here,’ I said, pointing to the nearest peak. ‘Up that valley then follow the spur to the main ridge. There’s that eroded step before the summit, but otherwise it looks pretty good.’

My companion made no reply.

‘Or that one,’ I said, gesturing to the sandy red massif to our right. ‘There’d be good climbing on that south face. Imagine the views!’

‘Yeah, imagine,’ the man said with a half-smile. ‘So which is it gonna be?’

‘That one,’ I said, nodding at the steeper of the two.

The man began to shovel the red mountain into a sack. We loaded it into the boot of my car. I gave him some money, and drove the peak home. Bricklayer Peak, I’d have called it. It was a real mountain all right, only one that had been rendered down to a pile of sand, then turned back into a mountain by wind and rain and time.

After more than a year in the Southern Alps for a book project, I’d been seeing scenic landscapes everywhere. Melbourne storm clouds were Aoraki’s glaciers. My rain-washed driveway became the Waimakariri seen from the air. Was this a Kiwi thing: everywhere you go, you always take the wilderness with you?

Like me, Conor Clarke is Kāi Tahu and living overseas. She whakapapas to Mangamaunu near the Seaward Kaikoura Range. I asked if she’d seen the corroded crags of Tapuae o Uenuku or Manakau in those piles of Berlin sand.

‘I saw “mountain scenery”,’ she replied. ‘What I saw I could relate to pictures of mountains, the epic, the immense, in a generic sense. I have been tramping before, and I have seen the Southern Alps, and the Swiss Alps from a distance … but I don’t know them intimately, only through depictions.’

Looking at Scenic Potential, her photos articulated what I’d missed at the quarry: that iconic mountains are built from both raw materials and a near-universal aesthetic code. William Gilpin’s rules for depicting scenery remain in force today. They teach us to frame wind and rain and time in ways that have nothing to do with any particular place.

There are other ways of framing mountains. Tapuae o Uenuku is a crew member from the Ārai Te Uru canoe; seeing him potentially recalls ancestral presence in the land. To the climber, that same peak offers potential routes to the top. To the entrepreneur it might be quarried for sand. But regardless, its potential is always also scenic. We’ve seen such mountains a thousand times. Which is why, when we see Conor’s meticulously constructed images, we assume we’re looking at nature itself.

Only, we’re not. What’s there is more honest. Tyre tracks, resembling the heavy machinery of glaciers, mark the images’ industrial origins. Mountain wildernesses were once literally bewildering. But as industrialisation rendered nature down into raw materials and sold them off, and life grew leisured and urban, Romanticism took hold. Escaping the ills of polluted cities to walk in the wild became a Victorian religion. Mountains became beautiful. Scenic Potential shows that the origin of mountain beauty is not in nature, but where Conor and I found it: in the quarries and factories of the West.

Nic Low is a writer and artist of Kāi Tahu and European descent. His first book, Arms Race, was a Listener and Australian Book Review book of the year. His second book will be a bicultural history of the Southern Alps told through walking journeys.

Solomon Mortimer Donavon Pinkerton #1 2013. Pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Miles Gallery, Auckland

Solomon Mortimer

There are apparent differences between a photographic self-portrait and a selfie; one is more constructed and the other casual, instantaneous. However, these self-portraits by Solomon Mortimer offer something distinct – a slowness of image that we all crave. In our hyper-mediated world images proliferate, whereas artistic photography remains still. It is this stillness that gives photographic self-portraiture its charm and vivacity.

Solomon’s self-portraits are the antithesis of his current practice, where photographs fragment the body, isolating moments and exploiting its commodification. To turn the lens on himself acknowledges the presence of the photographer, implying both a sense of performativity and self-criticality. And yet how does an artist create something new to meet an audience’s increasing demands for a breath of fresh air in a sea of representation? For Solomon the answer lies not only in technical skill but in a sensitivity to the construction of an image; a photograph is not just what’s included, it’s everything else that lies outside of it.

In this series of work, made predominantly between the years of 2011 to 2013, we see an artist taking pleasure in the play of representation, adopting a theatrical approach to image making, in a similar vein to the Pictures Generation of 1980s New York. Photographs are made both on the spur of the moment and as staged images; blending the divide between the real self and an imaginary one. In utilising photography as a medium with which to stage an image, Solomon is able to produce both fictional and accidental scenarios of masculine performativity by exploiting and embracing various tropes. In some photographs we might see his body stripped bare, exposed and vulnerable to the viewer; in another he becomes the quintessential soldier, the masculine citizen, ready to kill for his country. When these tropes are played out, their constructiveness and mythos are not only questioned, but they are seen for what they are – costumes for hire.

Interestingly these photographs were created without intention of exhibition; they are in a way more like a visualisation of a personal diary, a site of personal reflection. Perhaps it is for this reason that they speak of creative freedom, detached from the pressures of producing work for an audience. And because they form part of an ongoing series they retain an incompleteness, a quality that implies the indefinite. It is here that Solomon’s photographs feel intimate, authentic and easy. They offer a window into selfhood, through exposing its potential for renewal and rejuvenation.

Taylor Wagstaff has recently finished an MA at Elam School of Fine Arts and is currently a practicing artist based in Auckland. He is a regular writer for hashtag500words and works at the Auckland Art Gallery.

Ane Tonga Hoha’a 2013. Metallic print on aluminium Dibond. Collection of the artist

Ane Tonga

For the last eight years, Ane Tonga has worked on an ongoing project that explores Tongan concepts of gender through nifo koula (gold teeth). As her sister, I’ve been privy to her process and occasionally stepped in as an ad-hoc photography assistant. A few weeks ago we sat down at our parents’ home in Auckland to reflect on two bodies of work: Grills (2012–14) and Fakaētangata, (2014–16).

Nina Tonga: Do you think our father, who was a dental technician in Tonga prior to moving to New Zealand, influenced your interest in nifo koula?

Ane Tonga: Oh, for sure! Growing up, we learned so many weird facts about teeth and dental care that I think, subconsciously, influenced this project. He operated on mum’s nifo koula and worked directly with the dentists who implemented the procedure in Tonga… so I kind of feel like I made this for him, as well as the rest of our family.

Both the Grills photographs and the Fakaētangata are explorations of nifo koula, yet are quite different bodies of works. They do however share an ethnographic tension that must complicate your role as a photographer. What are your thoughts on this?

Because nifo koula had never been explored in visual culture, I was determined that these works didn’t become ethnographic by default or a universal truth that is reflective of nifo koula for all Tongan people. They’re not. They’re not studies of people or of the practice, they’re carefully constructed images that are intended to challenge and draw forth the tensions surrounding notions of gender and place that are embedded in nifo koula. Of course the images are informed by my own experiences, and equally the discussions with my family over many cups of tea.

Throughout your practice you’ve always been interested in the multisensory nature of site and landscape. Was the concept of site also important to your exploration of nifo koula?

Absolutely. Grills was produced in New Zealand and reflected the way in which nifo koula operates as a mnemonic device for Tongan communities living in diaspora. For many of my family members, they acquired their nifo koula in Tonga as a way of commemorating the trip. Often the gold used for the procedure was sourced from family jewellery, which added further layers of meaning. For Fakaētangata, I wanted to understand what nifo koula means for people, more specifically men who live in Tonga. Being in Tonga allowed me to give context to the adornment practice, the location of the toketā nifo (dentists) and more importantly the process. I’ve tried to capture the procedure in this series as a rite of passage.

There is a possibility that your works may be read as objectifying because they offer close-up photographs of the mouths of our family members. Was this your intention?

Focusing in on this part of their bodies was a way of protecting their identities. It negates the gaze. Also, often with artworks that depict the mouth, we never hear the voices of the subjects so I developed two moving image works to sit alongside the images, Malimali and Tohoaki’i. I wanted the videos to work as a powerful reminder that they are living, breathing, people and not objects for study.

Throughout these projects we have spoken a lot about film-maker Barry Barclay. How has his work inspired your practice?

His concept of fourth cinema was influential to me; it operates on ideas of reciprocity and privileges the view of indigenous communities. It is incredibly empowering and allows indigenous peoples to control the camera rather than be the subject of its gaze. As an indigenous photographer, placing Tongans in front of my lens became a tool to challenge the historical misrepresentation of Pacific peoples.

Nina Tonga is curator, Pacific cultures at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Shaun Waugh Drop-Shadow, Bluish Green 2016. Colour photograph, painted timber frame. Collection of the artist

Shaun Waugh

Drop shadows, a cluster of orange-red Agfa box lids, landscapes where forest remnants have been cut out of pasture and filled with washes of colour. Shaun Waugh’s photographs explore how we perceive solid colour.

In Waugh’s landscapes there is a vacuum, as if a suction has removed the patches of bush, and solid colour has taken its place. A void is made. Cut and colour, a form of deconstruction, renders a part of the image into nothingness; it shows intent, a hand. The landscape is not safe from manipulation. It is subject to whim and perception.

Whims can corrupt a landscape. Around the colour, nature has been mowed, fertilised, grass-seeded, fenced and irrigated. In the Department of Conservation’s terms, it is threatened: ‘likely to go extinct (or be reduced to a few small safe refuges) within the lifetime of those alive today.’

The colours obscure remnants of forest and bush on private land, much of which is protected by a covenant under the Queen Elizabeth II National Trust. The covenant ‘serves to preserve or to facilitate the preservation of any landscape of aesthetic, cultural, recreational, scenic, scientific or social interest or value.’ A few small safe refuges, secluded in the corners of farmland.

These colours are lifted from the GretagMacbeth ColorChecker® Chart. They were engineered to have a consistent appearance that would last through time and perception. Some of them are attempts to mimic those we see in nature: human skin tones, sky blue, leaf green, oranges and lemons.

Like a landscape, colour can be manipulated. Another series is titled ΔE2000 1.1, which is a measurement for colour; Δ, the Greek letter delta, stands for difference, and the E stands for Empfindung – German for sensation, impression, a strong feeling.

These photographs are each within ΔE2000 1.1 of the original orange-red of the Agfa box lid that frames them. In other words, the two colours are a match. Waugh’s reproduced orange and the box lid orange – the digital and the analogue – meet at the frame. A just-noticeable difference may divide them.

The drop shadow photographs also sample colours from the ColorChecker® Chart, and follow the same image/frame colour match process. Here, shadows, illusions of depth, are cast over a copy of a copy of a colour. One that was formulated in a lab to match a colour seen in nature.

Colour becomes the detail in these photographs. It obscures our vision. But there are variations in surface and tone, and within tone in shadow and under light. Maybe there are details reflected back, like in a mirror.

In the landscapes, colour seems to threaten to expand; to overwhelm nature and render it homogeneous and formless. Inside their box lids and frames, the colours have expanded to the point that the images are not photographs on a wall, but the colour itself.

Simon Palenski is a Christchurch-based writer. He has studied at the University of Canterbury and the International Institute of Modern Letters, Victoria University.

Rainer Weston Tweening #304 2016. Dye sublimation print on satin. Collection of the artist

Rainer Weston

In Rainer Weston’s short video work Liquid Crystal (2015), found footage slowly advances towards the viewer through a swarm of pixilation. Repeating continuously amongst the multitude is a segment from episode one of John Berger’s 1972 BBC series Ways of Seeing. This episode, which draws on ideas in Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, examines how the invention of the camera and subsequent reproducibility of an image changes the meaning and context of that which it captures. To pay attention to this particular piece of footage amongst all the others can, in some measure, work towards an understanding of the crucial considerations that Weston explores throughout his practice.

Traversing the interstitial space between traditional photography and technology, Weston’s diverse practice includes still life, appropriated imagery, 3D-rendering, photo manipulation and installation. This multi-faceted approach often produces work that is speculative of its own contemporaneity. His works are embedded in the language-forms of their own production, and self-reflective in that they acknowledge and celebrate this in their presentation and dispersal. They seek to interrogate the contemporary status of the image as an egalitarian cultural artefact.

Another of Weston’s recent projects, Tween Space (2016), involved both an online component and a physical show. ‘Digital Paintings’ were generated via an algorithm that produced a new work every hour, on the hour, for the duration of the show, which was installed in the small window gallery Rockies in Auckland. These works consisted of stock footage of the eponymous ‘Tweens’, partially obscured by strokes digitally painted over the surface of the images. This work, imbued with a subtly subversive wit, raised issues about the nature of artistic labour and well-known art historical questions about reproduction and authorship. On his personal Tumblr Weston quotes artist Parker Ito, who said, ‘I heard Picasso made around 250,000 works in his lifetime. I could make that many jpegs in 5 years. And when I say 5 years, I mean 5 minutes.’

The permeability of the image throughout networks follows a logic inherent to the late capitalist circulation of images. They accelerate through different online nodes, their visibility dependent on how many likes, shares and reposts are received on social media services such as Facebook, Instagram and Tumblr. This could be said to be true of the majority of visual culture consumed today, not just the images produced for, and circulated entirely within, the networks of the internet. The ease of dissemination, production and reproducibility made available with the widespread adoption of the smartphone has democratised image production and consumption. To return to Weston’s use of Ways of Seeing, the questions raised about the nature of the reproduced image and the context in which it is received become salient once again as we reflect on our contemporary society, where the internet plays such a crucial role as a vector in the transmission of information and visual culture.

James Hope is a graduate of the University of Canterbury majoring in art history and sociology. He divides his time between visitor hosting at Christchurch Art Gallery and working on various writing projects.

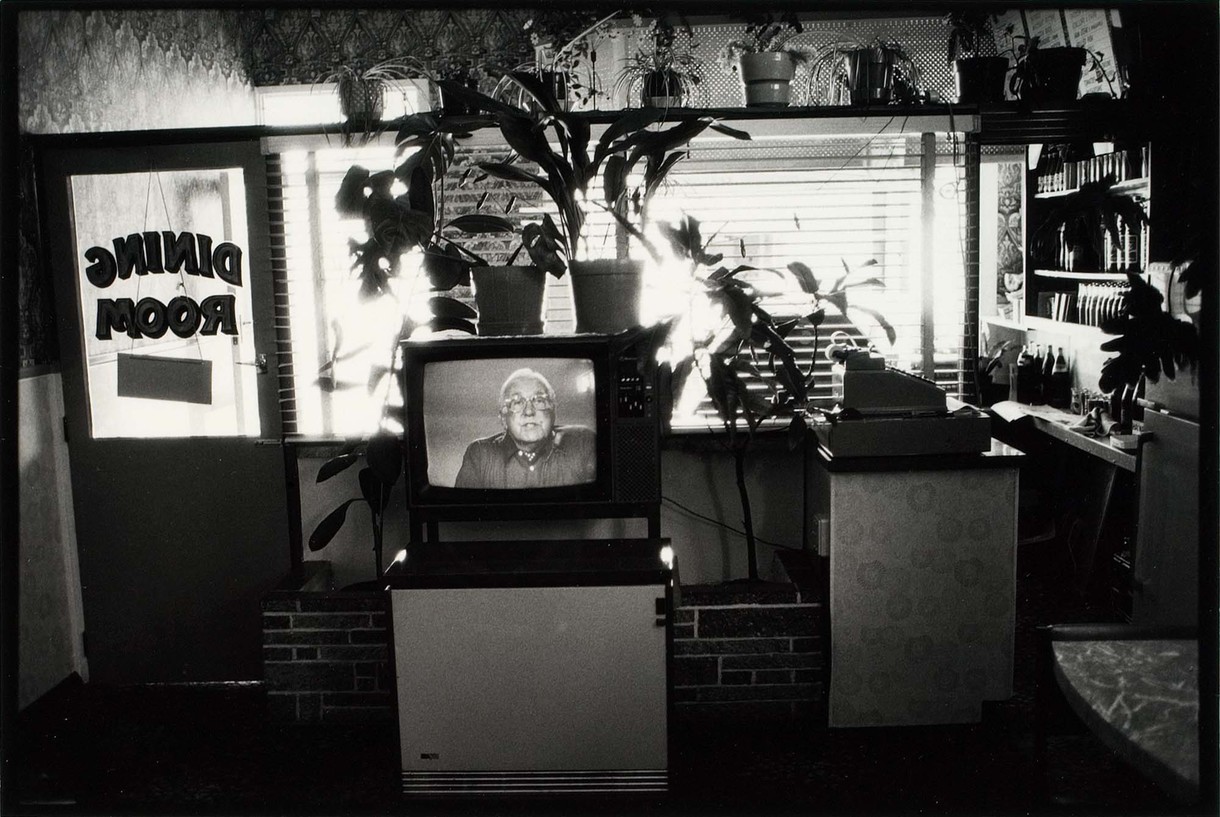

Chris Corson-Scott Winter Morning, Remains of the S.S. Lawrence, Mokihinui 2016. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist / Trish Clark Gallery, Auckland

Chris Corson-Scott

Chris Corson-Scott’s photographs are lyrical yet sparse ruminations on New Zealand’s history and current climate. They are interior and exterior ‘scapes’ that note the intersection between the landscape and human activity, fusing personal connection (when people appear in his works they are friends) with the weight of place. He cites the nineteenth-century work of John Kinder and Alfred Sharpe as an influence – both share detailed observations of the land and concern for the environment without sentimentality.

Landscape is a central trope that threads through New Zealand art history and reflects the importance of land: economically, spiritually and as a site of conflict. During the colonial period European settlers imposed their vision on the land: it was deforested, fenced and urbanised. Concurrently artists painted New Zealand’s landscape through the nostalgic lens of the art and light of Europe, in works that at times included Māori. Bush was tamed, thinned and enveloped in a romantic haze. Art mirrored life as the settlers sought to remake the landscape to match the Europe they had left. Throughout the twentieth century, the landscape continued to be subjected to the vision of artists as they sliced and reinterpreted it to fit their views.1 The current iteration is contained in advertising – 100% pure New Zealand, the mythical and unspoiled utopia.

By contrast, when considered within the lineage of the landscape, Chris’s photographs operate to reveal imposition on the land, and the social and economic issues that have occurred since European settlement. Aesthetically, the land remains intact. With its fundamentally realist characteristics, the medium of photography ensures that these works are true to the physical essence of place, as seen in the texture of wood, smoothness of the ocean and palette of the sky. Chris’s viewpoint comes through the carefully chosen subjects, revealing historical progression from colonialisation, industrial development and the current neo-liberal epoch. A shipwreck on a beach alludes to European settlement; deserted and decaying hop-kilns and freezing works rot in small towns left vacant by the collapse of industry; and at the fringes of the city, urban sprawl encroaches on nature. The presence or absence of artists in their studios is also a recurring theme: emblematic of carving a way of life separate from the mainstream, and currently under threat due to the acceleration of property prices.

The cultural theorist Roland Barthes wrote of the ‘punctum’ in a photograph, which could be a small detail or a component: that element which ‘rises from the scene’, that accident that ‘pricks’ and ‘bruises’ me.2 For me, the punctum in Chris’s photographs is in the absence and stillness that he photographs: sitting between the realism of the landscape and the social concern of his work. It envelops and slows, containing the force of history and the present, which is where we, as onlookers, linger.

Zara Sigglekow is a Melbourne-based arts writer and curator.