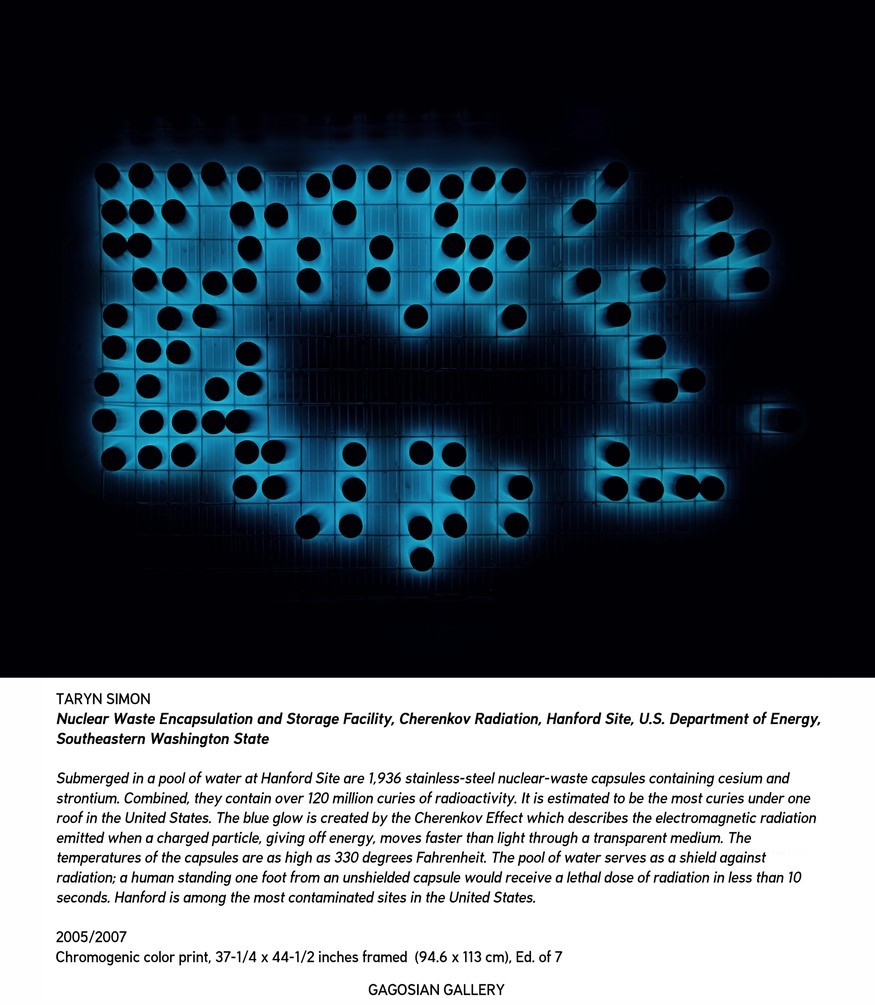

Larence Shustak

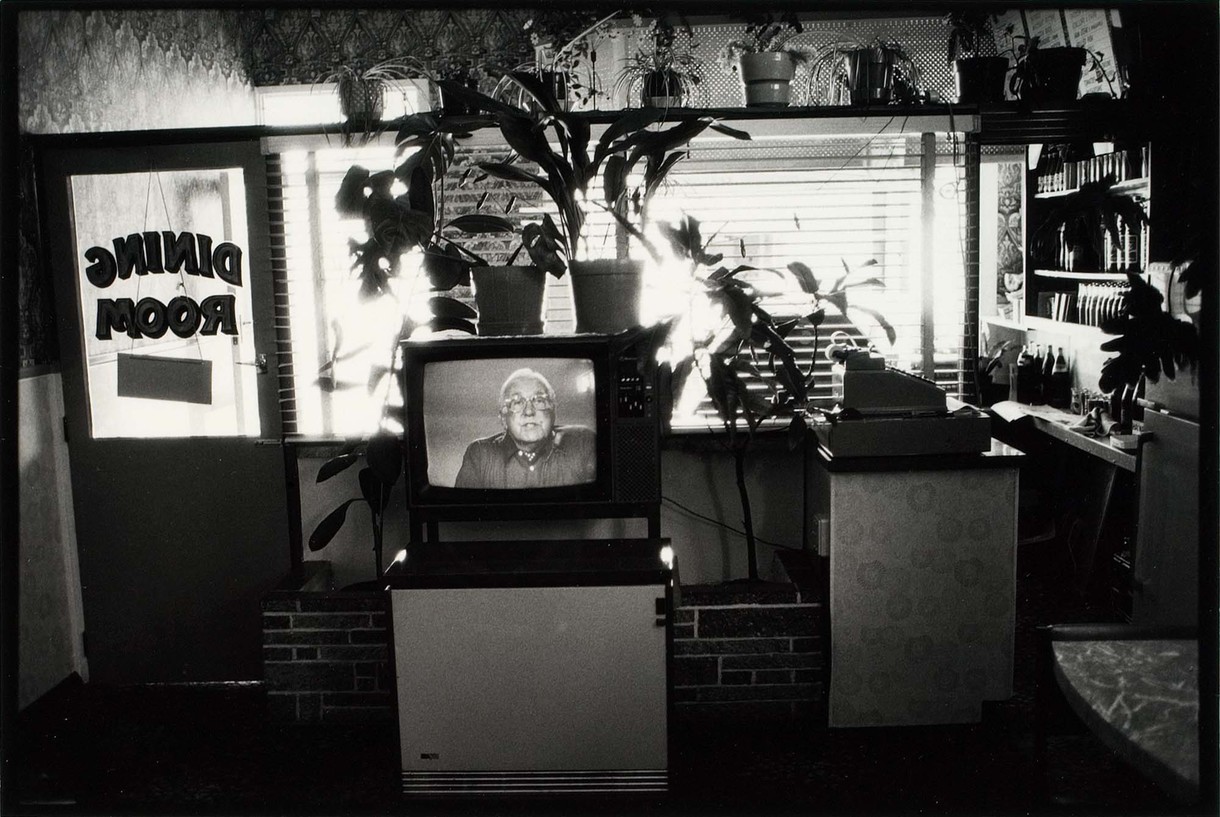

Larence Shustak Producer Orrin Keepnews, Riverside Records. Photograph. © Estate of L. N. Shustak

Welcome to the world of Larence Shustak—a rule-breaker and image-maker who came of age in the creative cauldron that was New York City in the 1950s. He used a camera as a paintbrush, documenting as well as creatively interpreting his subjects: street people and nudes. Old folks and children. Jazz legends.

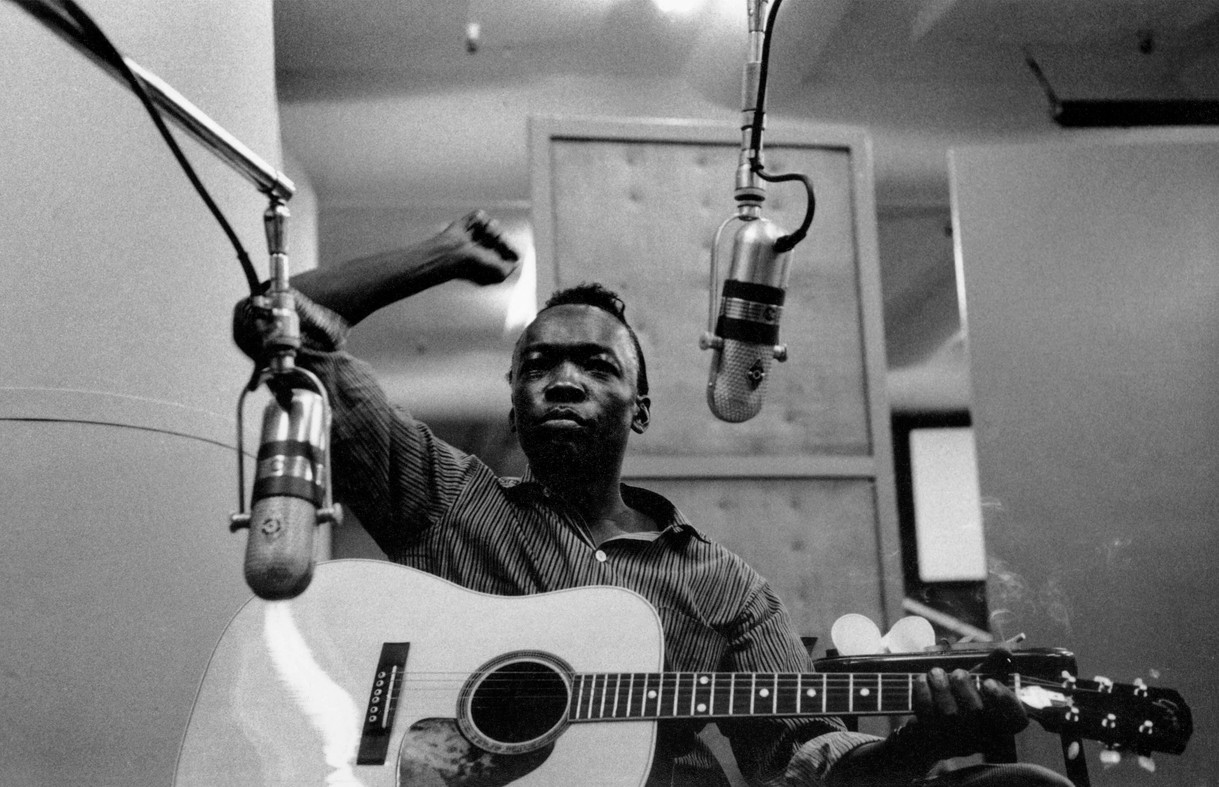

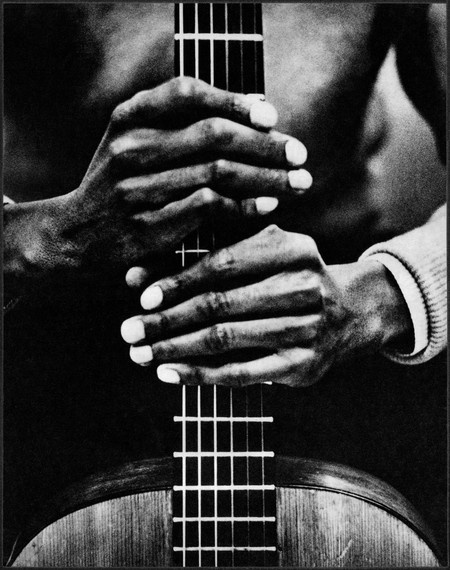

Larence Shustak Thought to have been either John Lee Hooker or Lightnin’ Hopkins, but actual subject unknown. Labelled as Musician’s hands, and also ‘Folk musician’s hands’ by Shustak on various different copies of the photograph. © Estate of L. N. Shustak

His eye favoured the unconventional and eccentric, and his black-and-white images still grab the eyelid and hold down the ‘pause’ button. He served as a professor at University of Canterbury and called Christchurch home for the last thirty years of his life. Apparently, he could be a terror in the classroom; “a brilliant and idiosyncratic teacher,” Photoforum called him. He is the subject of a documentary by a former student, filmmaker Stuart Page.

“I have an insatiable curiosity,” Shustak once explained, cognisant of the creative intensity and demanding nature that guided him to photography, and to find his own visual signature. “I am concerned with new realities arising out of familiar situations and sights.”

He came into the world in 1926 as Lawrence Nathan Shustak – his first name including the expected ‘w’ back then – born to a Yiddish-speaking Jewish family in the borough of the Bronx in New York City. His family’s roots stretched back to Belarus and Poland in the 1800s. It was an amazing time and place to be born: the Bronx was a vibrant, unplanned overlapping of a wide variety of immigrant groups and African-Americans; the network of apartment buildings and crowded city streets teemed with energy and all the sights, scents, and of course, music one would expect from a working-class collision of cultures. The family eventually moved to the less congested suburbia of Newark, New Jersey, but one can tell from Shustak’s later choice of subjects that he never stopped drawing inspiration from his urban cradle. After a stint in the military during World War Two – an experience which included serving as an interpreter researching military documents and prisoner interviews – he returned to New York City in 1946. He worked as a tool-and-dye maker until a trip to Europe in 1951 fueled his nascent interest in photography. By 1952, Shustak had found his path: passion and profession converged, and the camera became his means to creative expression and income.

Compared to today, it was a lot easier to work out that balance in New York City in the 1950s, and many artists did. A freelance photographer could generate enough revenue to pay for a small rental in Greenwich Village and put food on the table, while following their own muse. Shustak was single and young, and his photography – the images he shot for his own purposes as well as those for his clients – revealed an affection, bordering on exultation, for the city and its people. His high-contrast, black-and-white images began to bristle with a sense of surprise, offering the everyday in new, wondrous ways. Like other photographers of his generation who favoured candid, street-life shots – including future legends Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander – Shustak’s lens sought out individuality and eccentricity, startling moments and details, often starkly cropped. He honed his skill with the camera and in the darkroom as well, often spending an entire day printing and reprinting a single image until he was satisfied.

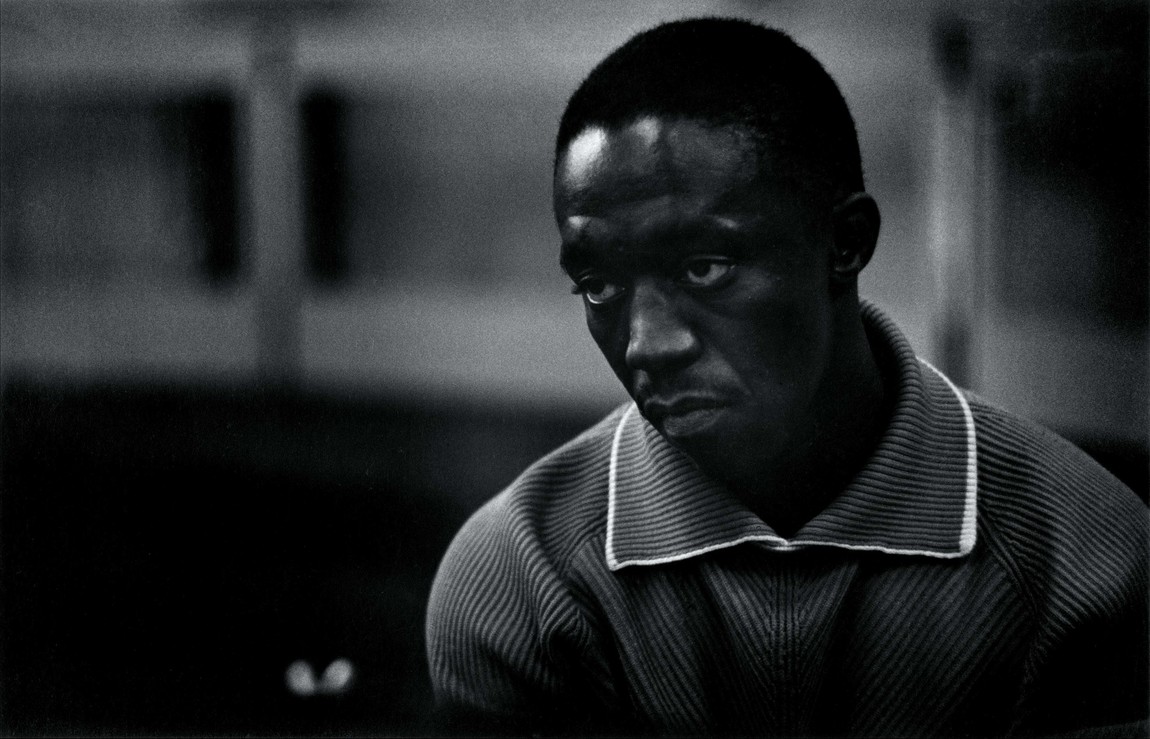

Larence Shustak Art Blakey (drummer), photographed in a Riverside recording session, NYC c. 1956–60. Photograph. © Estate of L. N. Shustak

By 1955, Shustak’s reputation had grown, and so had his client base. He was operating out of his own studio, producing images for magazines, book covers, company brochures and catalogues as well as actors’ portraits. Around 1956, he began to work with Riverside Records, an independent jazz label that was the new kid on the block at the time, taking photos for album covers and hanging at recording sessions – which brings us to the focus of this essay.

A word about jazz in New York City in the 1950s. To call it a golden age is too reductive, overlooking a nearly hundred-year musical timeline with many high points in various locations. But there was something about that music in that city at that moment in time. It was modern jazz, primarily performed by trios and quartets and quintets, a small-group extension of the big-band music that had come before. Like action painting, method acting and Beat prose and poetry – other creative crests attached to that period – modern jazz shared a fierce devotion to the freedom and excitement of the creative moment. Improvisation, a defining aspect of the fifties’ zeitgeist, was in its DNA. As abstract canvases and stream-of-consciousness writing focused on self-reference, where the act of expression became the subject, so had jazz become its own work of art. One jazz critic noted, “By the 1950s ... jazz [was] an object in itself, a non-functional music in the sense that it is no longer designed for dancing or background listening.”

The appeal of the music was furthered by a subdued, sophisticated aura. The jazz of the late 1950s was emotionally smouldering and more about subtlety and suggestion than grand gestures. Historian Dan Wakefield describes it this way: “The new sounds of Miles, Charles Mingus ... and then there was the incredible ultimate cool synthesis of classical music with fugue-like jazz, the Modern Jazz Quartet.” Whereas the fiery sounds of bebop in the 1940s had defined a particular lifestyle – an extroverted, rapid-fire aesthetic – in the late 1950s, things had changed. “All of a sudden, everybody seemed to want anger, coolness, hipness, and real clean, mean sophistication,” recalled trumpeter Miles Davis.

Larence Shustak Thelonious Monk—as seen on ‘Well You Needn’t’ (Riverside 7-inch REP 128) c. 1957. Photograph. © Estate of

L. N. Shustak

Larence Shustak John Coltrane at the Jazz Workshop, Boston MA 1963. Photograph. © Estate of L. N. Shustak

Miles was one leader in a pack of musicians who were moving the music forward in the late 1950s. Other members of this postbop brotherhood included pianists Thelonious Monk and Barry Harris, drummers Art Blakey and Max Roach, saxophonists John Coltrane, Johnny Griffin, Clifford Jordan, trumpeters Chet Baker and Blue Mitchell – all of whom Shustak would capture in the studio for the Riverside label, his photos appearing on a number of well-designed album covers that introduced the musicians and enhanced the listening experience.

Meanwhile, keep in mind that the advent of jazz on 12" vinyl discs – allowing for extended compositions and solos – was relatively new. The 33-1/3rpm LP (‘long-player’) record had debuted in 1948, and had taken a few years to catch on with music consumers, first with classical music and later more popular styles. Riverside Records – like fellow independent imprints Blue Note and Prestige – had helped bring the technological progress of the age, in the form of high-fidelity recording and the LP, to the jazz scene. Those vinyl discs needed to be packaged in a 12" square cover, and those covers needed images to help them stand out in the record stores. That need helped drive a new generation of photographers to apply their skills to this format, and soon names like Francis Wolff, Charles Stewart, Burt Goldblatt, Paul Weller and Carole Reiff were among the credits on the covers of noted jazz albums. Timeless music required images that would resonate as long. Add to that list: Lawrence N. Shustak.

Shustak’s camera may have been for hire, but his images make it clear he was a true jazz fan. They capture the intense intimacy of musicians at work. There’s a degree of closeness to his subjects – respectful, never invasive – that suggests a level of comfort and unspoken trust: the musicians accepted his presence in the studio, sometimes posing but often making, or preparing to make, music. It’s a closeness that defied the racial segregation of the day; Shustak’s reverence for African-American culture in general was a big part of it too. In turn, he honoured them and their space and carefully chose the right moment to snap the shutter.

It was an arrangement that yielded the iconic images accompanying this text: Thelonious Monk focused on the piano, the keyboard reflected in his dark glasses. SNAP. Riverside producer Orrin Keepnews amid musicians, microphones, and sheet music stands. SNAP. The expressive hands of John Lee Hooker. SNAP. The deep focus of Art Blakey, the sophistication of Max Roach and the intensity of John Coltrane. SNAP. SNAP. SNAP.

Larence Shustak Max Roach. Photograph. © Estate of L. N. Shustak

Looking back on those recording dates years later, Shustak explained to his students at the University of Canterbury that he accepted the work primarily to be with his heroes. Most of his black-and-white images were used on the back covers of Riverside’s recordings, windows into the session that produced the music; portrait photographers created the manicured shots for the front. But not always – a number of classic albums by the likes of Monk (The Unique Monk and 5 By Monk By 5), Roach (Deeds, Not Words), Nat Adderley (Work Song), Barry Harris (Preminado), Abbey Lincoln (Abbey’s Blue), Blue Mitchell (Blue Soul) and Jimmy Heath (The Thumper) all feature a Shustak shot on the front cover.

Shustak’s relationship with Riverside lasted into the early 1960s, ending when a shift in priorities and stature began to happen. Exhibitions, shows and press coverage in arts journals spread the news of his arrival as an artist. He began teaching – at the prestigious School of Visual Arts – and working in film, creating a number of shorts and documentaries. His photographic approach changed – experimenting with fish-eye lenses and, later, Polaroid cameras – and so did his subjects. In addition to street photography, he focused on nudes (using the fish-eye, memorably) and documented Black Jewish people, a study which yielded a book. By the early 1970s, after two marriages and looking for new worlds to explore, Shustak searched for a teaching position – first in Hawaii, then further west, across the dateline.

In 1973, Shustak relocated to Christchurch, taking a position at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Canterbury. ‘Lawrence’ renamed himself ‘Larence’, and spearheaded the establishment of a photography department at the school. He pursued other creative approaches through the next two decades, photography still his primary outlet. He retired in 1992 and never returned to live in New York City. Jazz remained part of his past, even as his images of the giants of the music acquired their own staying power and lasting influence. ‘Heroes’ Shustak called them, and in the way his camera caught them, they still are.