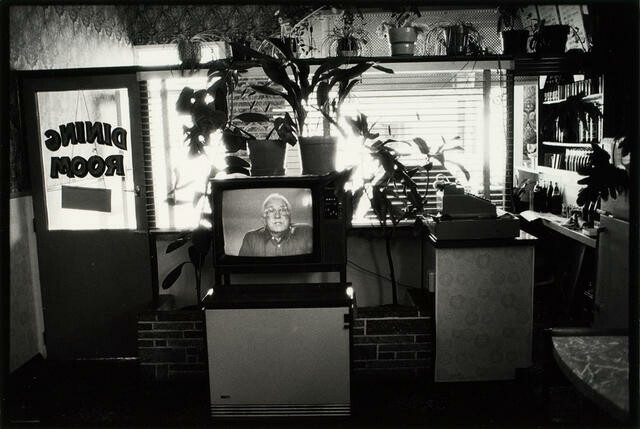

Selwyn Toogood, Levin

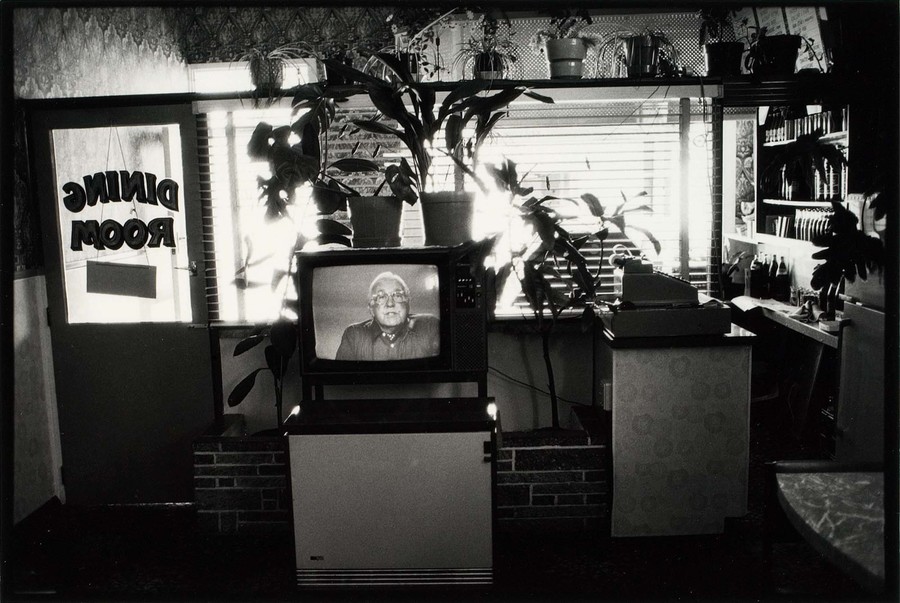

Peter Black Selwyn Toogood, Levin 1981, from the series 50 Photographs. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū 1988

I spent much of my adolescence in hospital, confined to bed due to a chronic illness. With a 14" TV beside me, I’d travel to imaginary places via the controller of my Nintendo games console. At the time, I couldn’t imagine walking to the letterbox, let alone experiencing the more exotic places of the world.

‘What’ll it be, New Zealand? The money or the bag?’

It’s little wonder that when finishing high school my ambition was to study to become an animator. I wanted to reside in my imagination and create fantastic and surreal worlds to get lost in. When I entered the Ilam School of Fine Arts I was completely naïve as to what life had in store for me. As the saying goes, I learnt pretty quickly – not without cajoling by lecturer Glenn Busch – that reality is sometimes much stranger than fiction. It was then that I first became aware of Peter Black’s work and declared I wanted to be a photographer.

Glenn talked of driving Peter around while he photographed out of his car window. He said that he couldn’t walk down the road with him and have a conversation because Peter would always be side-tracked and on the hunt for images. Glenn reckoned Peter was an obsessive breed of photographer that could transform everyday, banal things into extraordinary moments with his camera. I quickly learnt that this was no mean feat. To recognise the potential of a good photograph, to see something happening before you, and to frame and photograph it is one thing, but to articulate and sustain a personal voice within a series of photographs is quite another. Sitting in the studio at Ilam, I’d study my own proof sheets and compare them to Peter’s. We were photographing similar things; why were his so

much better? Then came a revelation. It was what his photographs implied, not what they depicted that carried weight. I realised the ambiguous mental space that fell just outside of view was just as important as the space rendered between the edges of each frame – that magic mixture of content, perspective, light, timing and composition. This changed my way at looking at art forever.

The first time I saw Peter’s Selwyn Toogood, Levin, I remember stopping in the City Gallery exhibition space and staring at Selwyn’s teeth, rendered bright white and Bugs Bunny like between awkwardly pursed lips. I imagined him being caught mid-sentence asking: ‘What’ll it be, New Zealand? The money or the bag?’ When I was a kid I’d shout ‘The bag!’ back at him, believing good fortune comes to those who take risks. Put in the contestants’ shoes now as an adult, pragmatism would dictate I’d choose the money – no matter how meagre the figure – to pay my astronomical power bill. From Selwyn’s teeth and lips, my eyes wandered the surface of the print and, after failing to adjust to the harsh light emanating through the window blinds, were drawn to the pot plants lining the top of the frame, the Formica table in the bottom right corner, the garish wallpaper. I then noticed the cash register and painted sign on the window of the door. This is a typically small town, Kiwi, dining establishment. A fish and chip shop, maybe? The angle of view is skewed just enough to imbue the image with a sense of unease.

Considering the context surrounding this photograph, I began to think about the social-political climate of New Zealand in 1981. After the Springbok rugby tour and with the country heading into steady economic decline, Muldoon’s National Party would soon be narrowly elected for a third term in government. Their time in power would be cut short with Muldoon calling a snap election. Many who care to remember cite this moment as the end of the ‘good old days’ and the birth of hardline, neo-liberal politics in New Zealand. In hindsight, perhaps what Selwyn was really uttering was a warning of things to come – the money or the bag?