Commentary

B.

Bulletin

New Zealand's leading

gallery magazine

Latest Issue

B.21701 Sep 2024

Contributors

Commentary

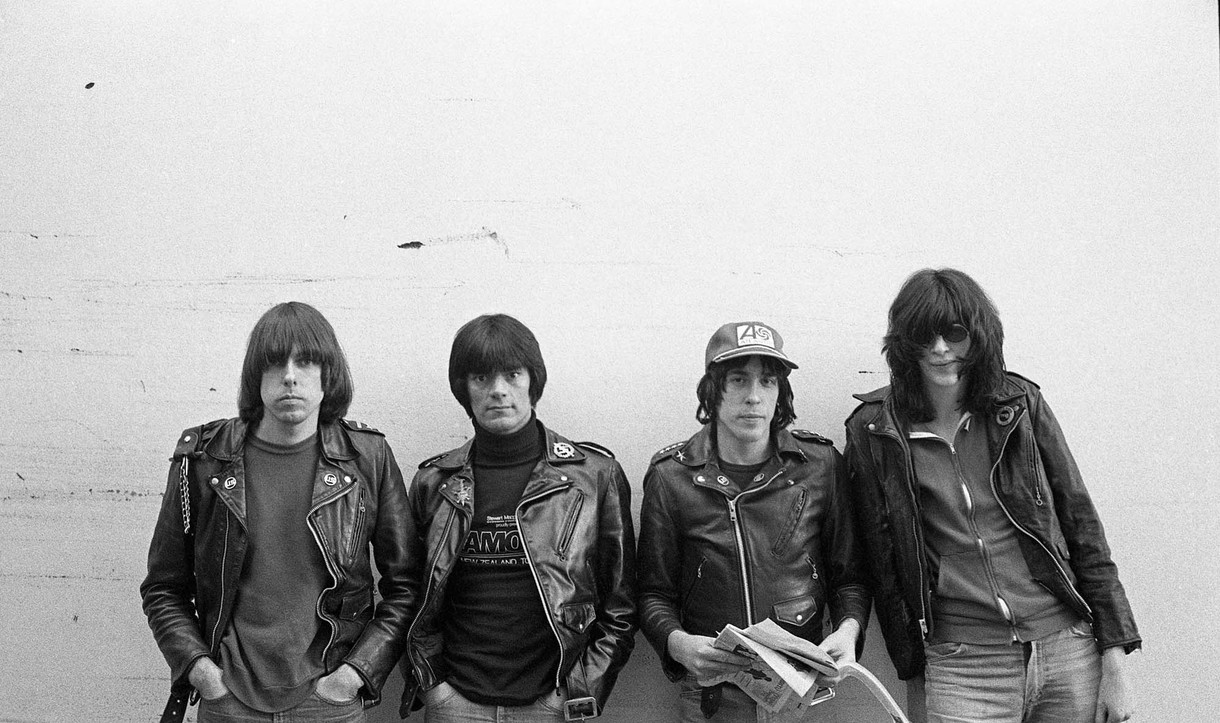

Laurence Aberhart

New Zealand artist Laurence Aberhart is internationally regarded for his photographs of unpeopled landscapes and interiors. He photographs places redolent with the weight of time, which he captures with his century-old large-format camera and careful framing. But he’s always taken more spontaneous photographs of people too, particularly in the years he lived in Christchurch and Lyttelton (1975–83) when he photographed his young family, his friends and occasionally groups of strangers. ‘If I lived in a city again,’ he says, ‘I would photograph people. One of the issues is that I even find it difficult to ask people whether I can photograph a building, so to ask to photograph them – I’m very reticent. I also know that after a number of minutes of waiting for me to set cameras up and take exposure readings and so on, people can get rather annoyed. So it’s not a conscious thing, it’s more just an accident of the way I photograph.’

Commentary

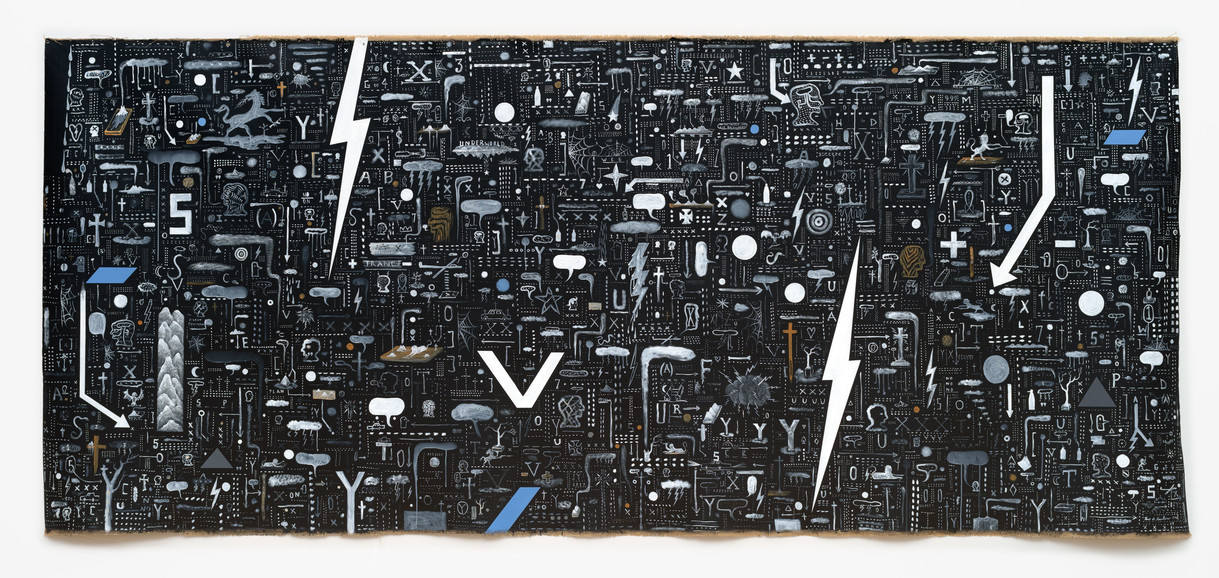

Your Hotel Brain

We recently opened a new collection-based exhibition, Your Hotel Brain. Curated by Lara Strongman, it focuses on the cohort of New Zealand artists who came to national – and in some cases international – prominence in the 1990s. The title of the exhibition is a phrase drawn from Don DeLillo’s epic novel, Underworld, published in 1997. It gestures towards the way that pieces of information float through your mind, checking in and out, everything demanding attention, everything happening all at once – a metaphor for postmodernism in the 1990s and for the increasing slippage of context in the digital era. The 1990s were a time of great social and cultural change in Aotearoa New Zealand, set against a broader backdrop of globalisation and the rise of digital technologies. Artists, as ever, registered these cultural shifts early. We asked a number of people who were working in the arts at the time to recall their experiences of the 1990s.

Commentary

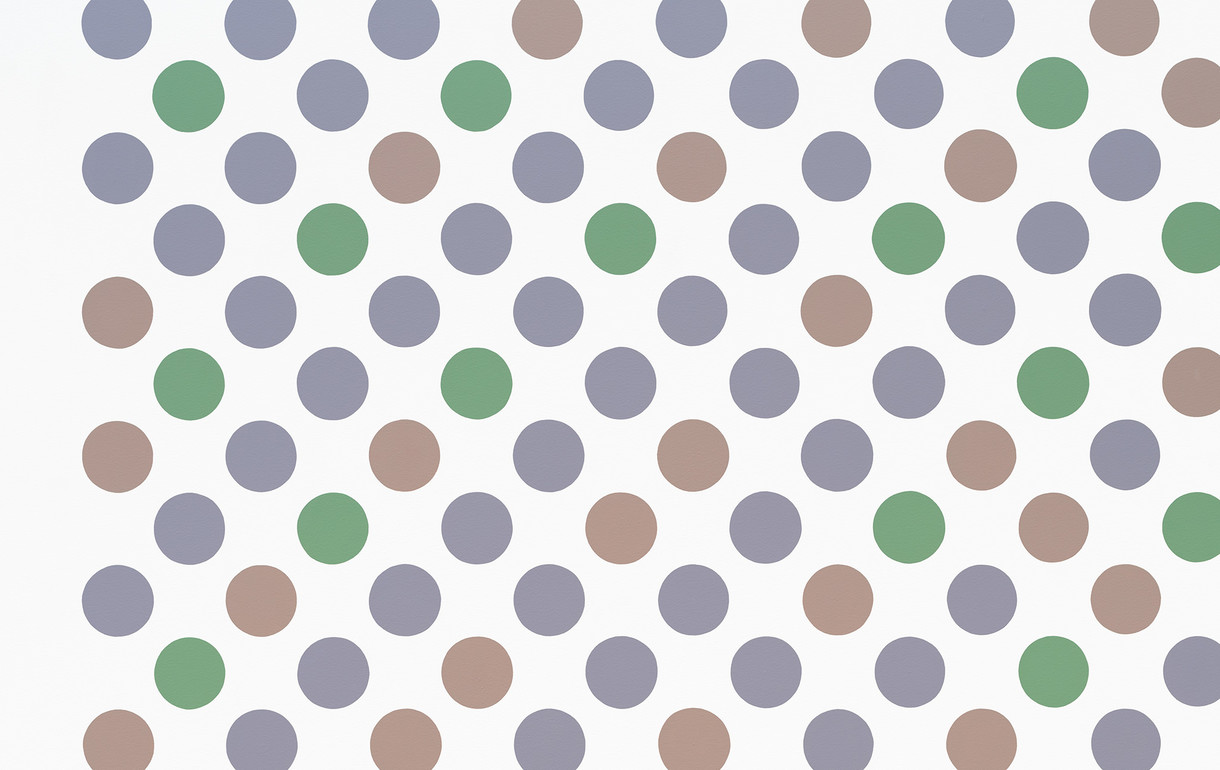

Our Instinct Enhanced

What does Bridget Riley’s art mean? We might imagine that a wall painting titled Cosmos (2016–17) referred to life within a cosmos, an order than encompasses us, whether natural or divine. The designation connotes a degree of philosophical speculation, unlike the direct descriptions that Riley occasionally employs as titles, such as Composition with Circles. But whatever meaning we derive from viewing Cosmos will be no more intrinsic to it than its name. Attribution of meaning comes after the fact and requires our participation in a social discourse. Every object or event to which a culture attends acquires meaning; and Riley’s art will have the meanings we give it, which may change as our projection of history changes. Meaning, in this social and cultural sense, is hardly her concern.

Commentary

Bringing the Soul

As an eleven-year-old boy from Whāngarei, sent to live in Yaldhurst with my aunt in the late seventies, Christchurch was a culture shock. Arriving in New Zealand’s quintessential ‘English city’, I remember well the wide landscapes and manicured colonial built environment. It was very pretty but also very monocultural, with no physical evidence of current or former Māori occupation or cultural presence, or at least none that I could appreciate at that time.

Commentary

Such Human Tide

The exhibition He Waka Eke Noa brings together colonial-era, mainly Māori, portraiture alongside objects linked to colonisation – it’s a predictably uncomfortable mix. While the degree of discomfort may depend on one’s background or degree of connection to an enduringly difficult past, objects related to emigration and colonisation can be a useful lenses. As relics from a specific period in global history, when the movement of (particularly) European people was happening at an unprecedented scale, they hold stories with a measure of complexity that obliges an open-minded reading. There is no denying that they speak of losses and gains, of injustices and rewards.

Commentary

Energies and Apparitions

This essay was written by curator Anna Davis for the Energies: Haines & Hinterding exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia in 2015.

The art of David Haines and Joyce Hinterding is characterised by its openness to the unseen forces that permeate human experience. Very low frequency (VLF) radio waves, television signals, paranormal events, satellite transmissions and psychic energies are all manifest within their work, which aims to summon these hidden realms and bring them to our senses. Using experimental and traditional media, they engage in an artistic dialogue with science, intersecting with areas such as electronics, solar research, geology, olfactory chemistry and high-energy physics. Aesthetic and metaphysical concerns are equally vital to their practice, which also traverses speculative and esoteric domains such as Reichian orgone energy and Kirlian ‘spirit’ photography.

Commentary

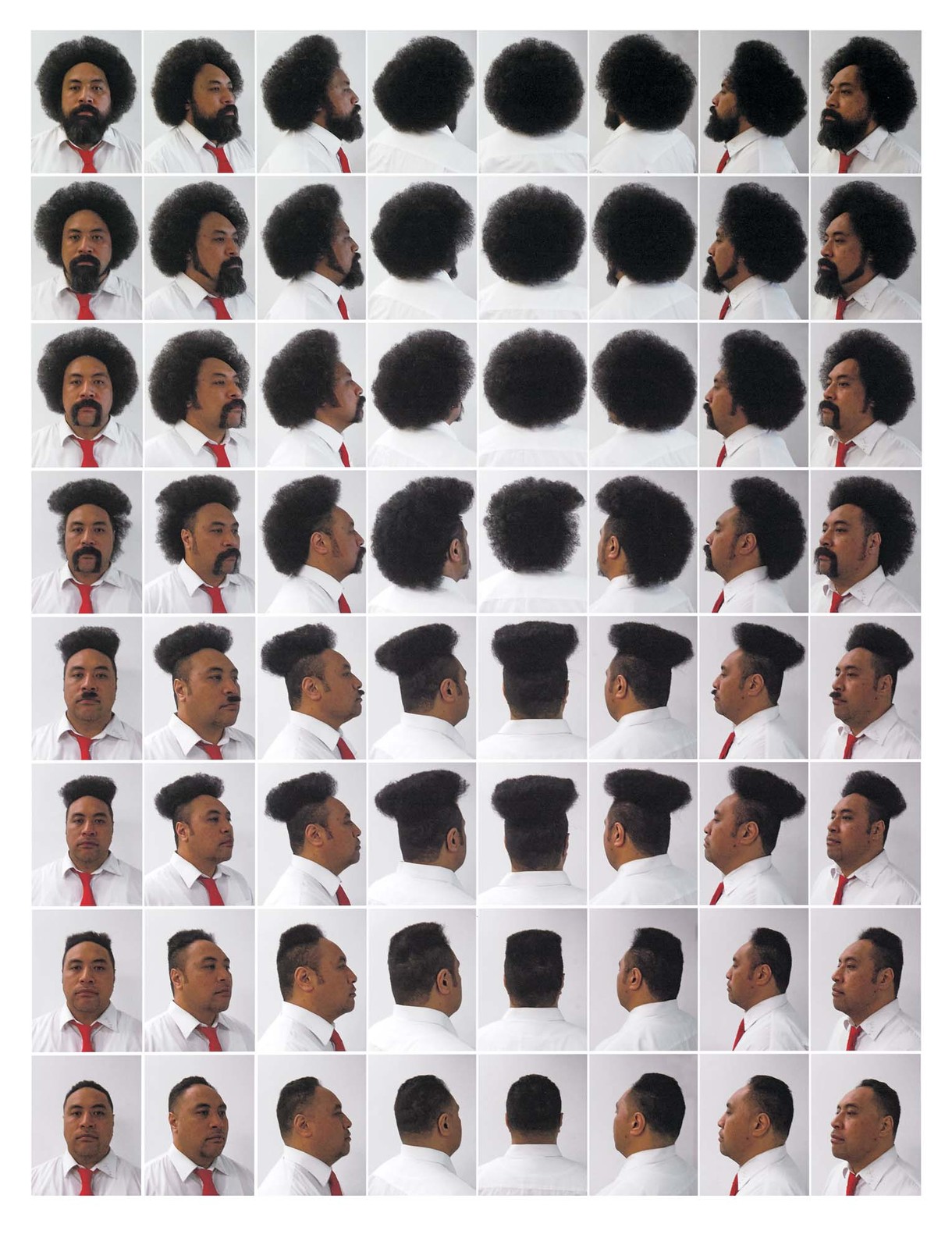

Hair Story

In drawing attention to the theatre of personal grooming, Bad Hair Day brings together portraiture and caricature with a variety of less readily classifiable works of art. The densely packed selection spans a vast historical range. And in putting bowl cuts and bushy beards alongside wayward wigs and whiskers, it highlights the sometimes comical aspects of hair, especially when styles are extreme. If wry intent is discernible throughout the exhibition, however, we shouldn’t let this fool us: hair is a topic that easily turns serious.

Commentary

Reading the Swell

The art of the sea has always been the art of vastness—without edges and with potential for infinite extension. It is this immensity that has invaded the Reading the Swell exhibition; finding its way through the automatic doors when no one is looking and quietly expanding the walls. Like sailors, artists have laid soundings in this uncharted vastness. Reading the Swell is a small and pointed selection of those soundings that see fit to make sense of the sea.

Commentary

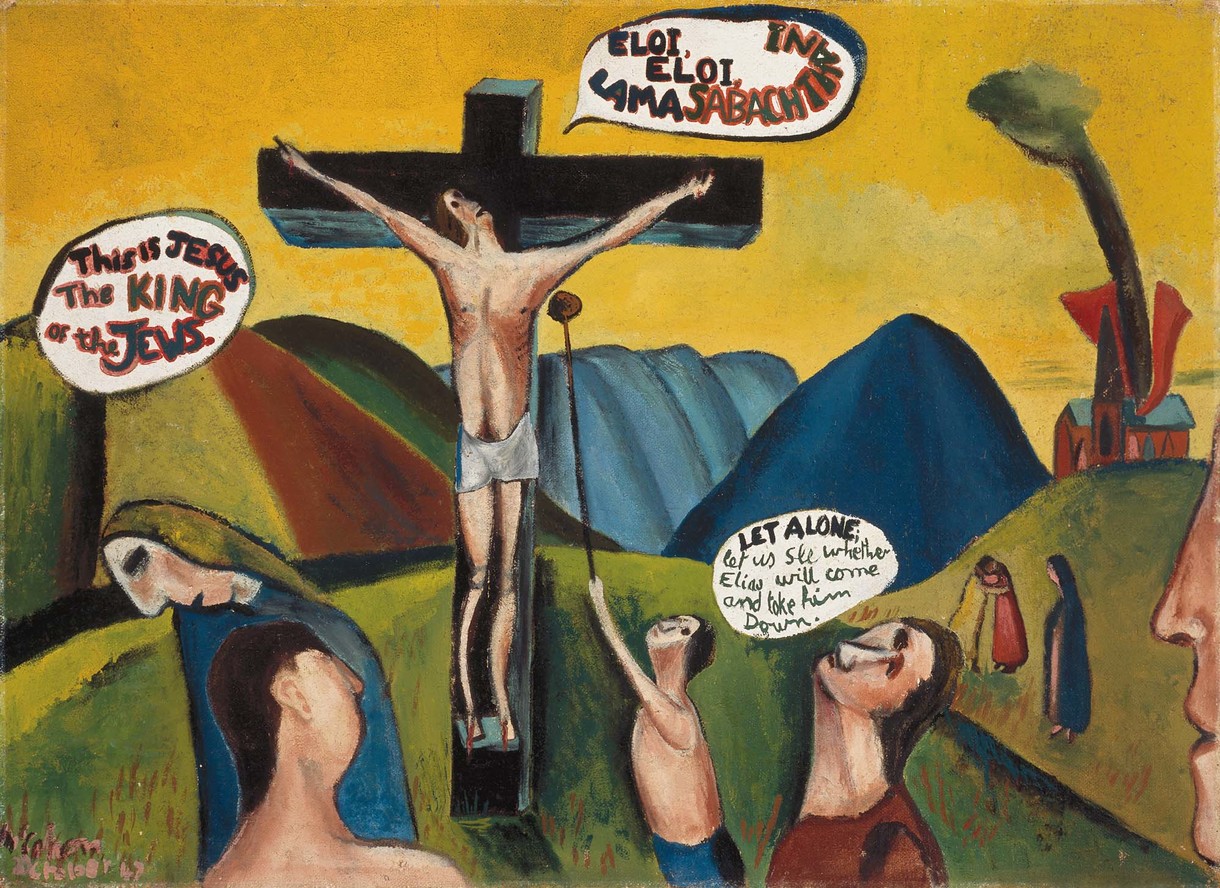

Colin McCahon: Five Years in Christchurch, 1948–53

Prior to moving to Christchurch in March 1948, Colin McCahon and his family spent a little over a year living in Muritai Street, Tahunanui, on the outskirts of Nelson city. It was his most productive period as a painter to date – a phase dominated by figurative paintings with some landscapes. The products of this prolific period were brought together in his first major one-person show, at Wellington Public Library in February 1948, organised by his Dunedin friend, Ron O’Reilly. An exhibition of forty-two works made between 1939 to 1948, more than half produced in 1947, it consisted of roughly equal numbers of landscapes (including Otago Peninsula and Maitai Valley), biblical paintings (King of the Jews, Crucifixion according to St Mark ), and non-biblical figurative works (A candle in a dark room, The Family). Although it was reviewed favourably in The Listener by J.C. Beaglehole, the subsequent letters column ran hot with controversy, and it brought McCahon to national attention.

Commentary

The Lines That Are Left

Of landscape itself as artefact and artifice; as the ground for the inscribing hand of culture and technology; as no clean slate.

— Joanna Paul

The residential Red Zone is mostly green. After each house is demolished, contractors sweep up what is left, cover the section with a layer of soil and plant grass seed. Almost overnight, driveway, yard, porch, garage, shed and house become a little paddock; the border of plants and trees outlining it the only remaining sign that there was once a house there.