Energies and Apparitions

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding Encounter with the Halo Field 2009/15. Single channel video, sound, 3.38min. Commissioned by the Australian Network for Art and Technology and Art Monthly Australia, supported by the Australia Council for the Arts. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2015

This essay was written by curator Anna Davis for the Energies: Haines & Hinterding exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia in 2015.

The art of David Haines and Joyce Hinterding is characterised by its openness to the unseen forces that permeate human experience. Very low frequency (VLF) radio waves, television signals, paranormal events, satellite transmissions and psychic energies are all manifest within their work, which aims to summon these hidden realms and bring them to our senses. Using experimental and traditional media, they engage in an artistic dialogue with science, intersecting with areas such as electronics, solar research, geology, olfactory chemistry and high-energy physics. Aesthetic and metaphysical concerns are equally vital to their practice, which also traverses speculative and esoteric domains such as Reichian orgone energy and Kirlian ‘spirit’ photography.1

'My interest is energy, transference of energy …'

David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding The Levitation Grounds (detail, still) 2000/15

In a recent interview, Haines described his and Hinterding’s relationship not as one of ‘consensus’ but of ‘intense conversation’;2 it is this vigorous exchange of ideas that has developed into their dynamic artistic collaboration. The two artists have been working together for more than 15 years, and their collaborative practice brings together Hinterding’s work with acoustic and electromagnetic phenomena and Haines’ hallucinatory video worlds and aroma-based compositions. The artists also maintain their solo practices and have developed a mode of living together and making art that allows them to work collaboratively on major projects and independently on their other works, which are, as they put it, ‘individual yet related’.3

Hinterding has spent more than 25 years working with vibrating objects, building aerials for listening to the electromagnetic landscape and creating graphite drawings that also function as circuits and graphic antennas. Haines’ work stems from an early practice in Colour Field painting, video, photography and sound. He has also worked for almost a decade with aroma, composing fragrances inspired by plants, the earth and the cosmos. Haines’ and Hinterding’s collaborative practice is perhaps best described as a kind of multisensory science fiction in which actual phenomena and imaginary realms intersect, stimulating experiences that are unfamiliar both to science and the visual arts.

A useful way of approaching their art is to observe the distinctive set of tools, materials and processes they employ in its creation. Their tools include a range of hacked and custom-built devices, from computer game engines and hardware systems used to build virtual worlds, to antennas for monitoring and recording electromagnetic signals in the environment and cameras designed to capture images of the sun and the ‘aura’ of plants. Like many artists they use pencils, paper, video and sound, but their materials are also energies and vibrations – lightning, natural radio,4 TV static and aroma molecules. Finally, in terms of process, much of their art emerges from informal experiments they conduct in and around their home and studio, a house on the edge of bushland in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, where they have lived since 2004. These experiments involve fieldwork: periods of observation and data recording often in remote locations, followed by long hours of work in the studio, where the collected data is reimagined and manipulated in various ways.

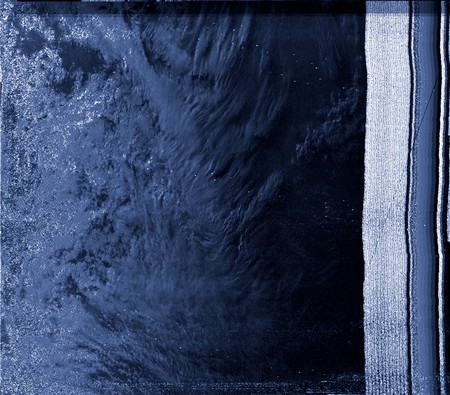

The artists’ first collaborative work, The Levitation Grounds (2000/15), is a four-channel video installation they made during a residency at Cape Bruny Lighthouse on Bruny Island off the southern coast of Tasmania. It combines field recordings of very low frequency (VLF) radio waves with satellite data and digitally manipulated images of the harsh Tasmanian landscape. On one screen, a rough sea batters Bruny Island’s jagged dolerite coast, its waves washing violently in and out of a gaping cave. On two others, dead trees float in the air, gliding past each other in an eerie forest clearing. Accompanying these dreamlike images are the mysterious sounds of the VLF, a low bass hum sprinkled with higher pitched crinkly and glittery sounds. These are the shimmering noises of natural radio heard at the VLF frequency. The sounds are mirrored by tiny glints of light in the digitally manipulated forest, adding to the impression that the energy we are hearing is somehow related to the mysterious levitation event. In contrast to these heightened cinematic scenes, there is also a drab monochrome image that initially seems to consist only of repetitive lines and glitches. This data readout of signals from orbiting polar satellites also includes low resolution images of the earth’s weather from the satellites’ cameras, and is accompanied by machine-like sounds of evenly spaced buzzes and beeps.

When asked to remember how they made the work some 15 years ago, Hinterding recalls wanting to go somewhere ‘remote’, a wish that was granted by the site on Bruny Island, which she describes as being ‘at the bottom of the world, and completely off the grid’. Remembering the experience, the artists describe the island’s strange weather, which could engulf them in a matter of minutes, its access to cosmic transmissions such as the aurora australis (or ‘southern lights’), the overall spookiness of the place and the weight For Haines and Hinterding, the experience of sharing Bruny Island’s haunted sites and dynamic cosmic ecology was the spark that ignited their artistic collaboration. As Haines recalls:

Joyce had built a radio receiver for listening to satellites and we were bringing in radio feeds from outer space and working with the sound of the VLF. At the same time, I was teaching Joyce how to use 3D [software] to create virtual worlds.

For those unfamiliar with its workings, 3D software can create a virtual world on screen, using mathematical equations to affect forces such as gravity and the weather within the simulated environment. This potential within the computer program gave the artists what they describe as the ability ‘to keep going and play with forces in the world’. By combining cinematic renderings of the landscape and its strange weather with electromagnetic field recordings, they formed a new kind of intermedia aesthetic that they would continue to expand upon in later works. This crucial moment of collaborative synthesis highlighted the artists’ shared interest in experiential and fabricated worlds, aligning the strangeness of invisible forces in the ‘natural’ environment with the uncanny familiarity of images that simulate the paranormal.

Discone Antenna, Bruny Island, Tasmania, Spectral — Audio CD. Photo: Joyce Hinterding

Like a number of their later works, The Levitation Grounds merges images and sounds of the natural environment with a palpable sense of the supernatural. For Haines the highly constructed space of the video image has always been a ‘hallucinatory palette’ that allows him to combine the real and the imaginary. It was in The Levitation Grounds that this palette was first brought together with Hinterding’s artistic invocation of invisible, real-world energies. However, the artists’ shared affinity with the supernatural can be seen throughout their work. For instance, many of Haines’ screen-based works are of worlds subject to occult forces. His early black-and-white video A Golden Autonomy (1999) follows a small ghost through a suburban landscape, while in another monochromatic work, Born to be Wild: Silver Hill (2004), a plantation of pine trees falls down for no apparent reason.5 In his two-channel video installation The Seventeenth Century (2002), a quiet scene of suburban apartments is disturbed by a jet of purple ectoplasm that erupts quietly into the night sky, a disconcerting image that is accompanied by another of toxic yellow smoke, billowing upwards like acrid emissions from the mouth of an erupting volcano. Haines grew up in a house in Sydney’s western suburbs that was said to be haunted and his mother was very interested in the occult, so it is perhaps no surprise that his video works seem to pulsate with the strange forces of the spirit world. What intrigues him is how he ended up with a collaborator like Hinterding, whose work invokes the vibrational forces inside things, unlocking their occult potential.

Hinterding’s affinity with the occult can be seen vividly in her early works, such as the remarkable Koronatron: 24 Winds of the Sparkling Globe (1996), which was installed in the massive Gasometer exhibition space in Oberhausen, Germany. A site-specific installation, it used reconfigured cathode ray television components and photovoltaic (solar power) technologies to translate sunlight on the roof of the structure into high-voltage electrical discharges at the top of the tower. The deadly 25,000-volt sparks leapt between 24 pairs of aluminium spheres that were suspended from the industrial structure’s ceiling. From a viewing platform some 110 metres above the ground, the miniature lighting strikes could be seen burning the air, creating cracking and hissing sounds in their wake.6

In another early installation, Electrical Storms (1992),7 Hinterding employed two sets of glimmering electrostatic speakers, one playing VLF recordings from a fieldtrip to Walter De Maria’s seminal land art work The Lighting Field (1977) in New Mexico, and the other playing live sounds from a VLF antenna she had installed in the gallery’s roof in order to monitor electrical activity in the volatile Sydney summer atmosphere.8 As Ann Finegan suggests, in works such as these Hinterding takes on the role of a magus, bringing the hidden world of electromagnetic forces into the gallery by ‘disrupting the order of things, just a little … to allow the unseen to manifest’.9 While Hinterding may not entertain any supernatural fantasies, there is something enigmatic about an artist bringing the power of the electromagnetic universe into the realm of art.

Hinterding began her artistic career in gold and silversmithing, working with metal to create resonant acoustic objects, and eventually going on to study electronics at TAFE in order to learn how to work with the vibrational world of the electromagnetic landscape.10 Remade for the MCA exhibition, Aeriology (1995/2015) is a major work from this early period that explores the idea of sympathetic resonance, incorporating materials, forms and energies that would continue to reverberate throughout Haines’ and Hinterding’s collaborative practice. Made from 15–20 km of thin copper wire hand-coiled around columns within the MCA gallery, Aeriology resonates in sympathy to inaudible radio frequencies in the environment that are related to the wire’s length and physical dimensions. The frequencies Aeriology attracts arise firstly from its local site – the fields emanating from the electrical wiring in the gallery and from nearby electronic equipment. Beyond this, the huge coil also picks up radio waves originating from the rest of the MCA building, the city’s electrical grid, the sun and other stars deep in the galaxy. Energy collects in the wire and is made audible through an amplifier. Two oscilloscopes offer a visual representation of the invisible electromagnetic waves. Significantly, in this era of climate change and the search for ‘green’ fuels, this is an artwork that powers itself, gathering lost energy and transforming it into electrical activity in the wire.11

Joyce Hinterding Siphon 1991. Glass, circuitry, installation view, Australian Perspecta 1991, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney Photo: Ian Hobbs

Aeriology is a functioning antenna, but one that is intentionally oversized and susceptible to a wide range of frequencies. Unlike an engineer, Hinterding is unconcerned with efficient antenna design and instead has constructed a shimmering copper veil that draws attention to the hidden vibratory world permeating our bodies and energising the planet. In Siphon (1991),12 the artist took another well-designed electronic component, in this case a capacitor,13 and stretched it to its outer operational limits. Made of 300 beer glasses, each one coated with a thin layer of graphite, wired together in a messy grid of black cabling on the gallery floor, Siphon was reported to have smelled strongly of electricity and to have produced strange sounds that were associated with the resonant frequency of the beer glasses as they were filled and emptied with an electrical charge.14 Summoning the power of electricity and channelling it through a strange home-made apparatus, Hinterding kindled a sense of wonder at the energy so often taken for granted in our electronic lives. The work’s inherent volatility, its scorched aroma and its amplified audio brought to mind the dangers associated with invoking forces outside our control.15

Astonishment at the power of invisible forces also pervades stories of the supernatural, and this is one of the key areas where the worlds of Haines and Hinterding intersect. While Hinterding has long been spellbound by the vibrational energy that exists inside all things, Haines has been mesmerised since childhood by the atmospherics of haunted houses – potent sites where architecture, landscape and psychic worlds combine.

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding The Blinds & the Shutters (detail, still) 2001/15

The house is a dominant figure in Haines’ and Hinterding’s work, a fundamental human structure that witnesses both life and death, as well as the more mundane aspects of everyday experience. For Haines these ‘psychically overcharged architectures’ are ‘either haunted or they’re not’ and can be measured by the intensity of their atmosphere. The artists’ home in the Blue Mountains is deliberately wired to function as a huge radio antenna, and Hinterding speaks of it fondly as both a potential scavenging ground for gathering excess energy from the electrical grid and a protective magnetic shield from the radiation lost by nearby power lines. In their collaborative installations, Haines’ attraction to the uncanny disturbances of house and home intermingles with Hinterding’s preoccupation with the invisible energies that both permeate and comprise these structures.

Much of the artists’ work arises from their responses to the architecture, technologies and landscape of their local environment. After their Bruny Island excursion, their next collaborations (1999–2003) were made while they were living in a cliff-top apartment in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. Positioned near the north end of Coogee, their airy perch on the top floor gave them 180 degree views of the ocean and the seemingly endless southern coastline stretching into the distance. Hinterding describes feeling ‘swept up in the forces of the world in that apartment’, a sensation that is mirrored in their second collaborative work, The Blinds and the Shutters (2001/15). In this four-channel video installation, which for this exhibition has been converted into a digital format experienced using a virtual reality headset, all manner of domestic objects – clothes, books, plates, cups, a television, bedsheets, tables and chairs – can be seen floating away from a white modernist house in the Australian bush. The items swirl in the air in front of the house on one screen and soar leisurely into the cosmos on the others, ultimately disappearing – perhaps sucked into a black hole or some other kind of cosmic vortex? Standing in the middle of the four virtual screens gives viewers a multi-perspective vantage point and the impression of being suspended in the midst of an extraordinary occurrence. Watching the events unfold, one can imagine the owners of this stylish home frantically chasing their possessions as they see them spiral upwards and vanish into the heavens, blaming either a malevolent spirit or some equally mysterious anti-gravitational pull.

The audio in The Blinds and the Shutters comes from field recordings Hinterding made of the electromagnetic landscape in and around their Coogee home. Rather than recording the sounds of the ocean thrashing against the cliffs outside, she tuned into a range of other inaudible waves. Using portable antennas she recorded the process of moving in and out of the electromagnetic fields emanating from the technologies they were using at the time. These included what would now be considered extremely out-of-date computers and large analogue television monitors (cathode ray tubes) she describes as ‘incredibly violent structures that literally shoot electrons down a vacuum right at your face’. Cathode ray technology is sometimes referred to as being like a model of the cosmos, able to produce charged particles in a vacuum that can simulate the electromagnetic nature of the universe.16 The artists continue to be intrigued by this idea, Haines speculating that ‘we think of cosmology as the big outside but it’s also the interior.’

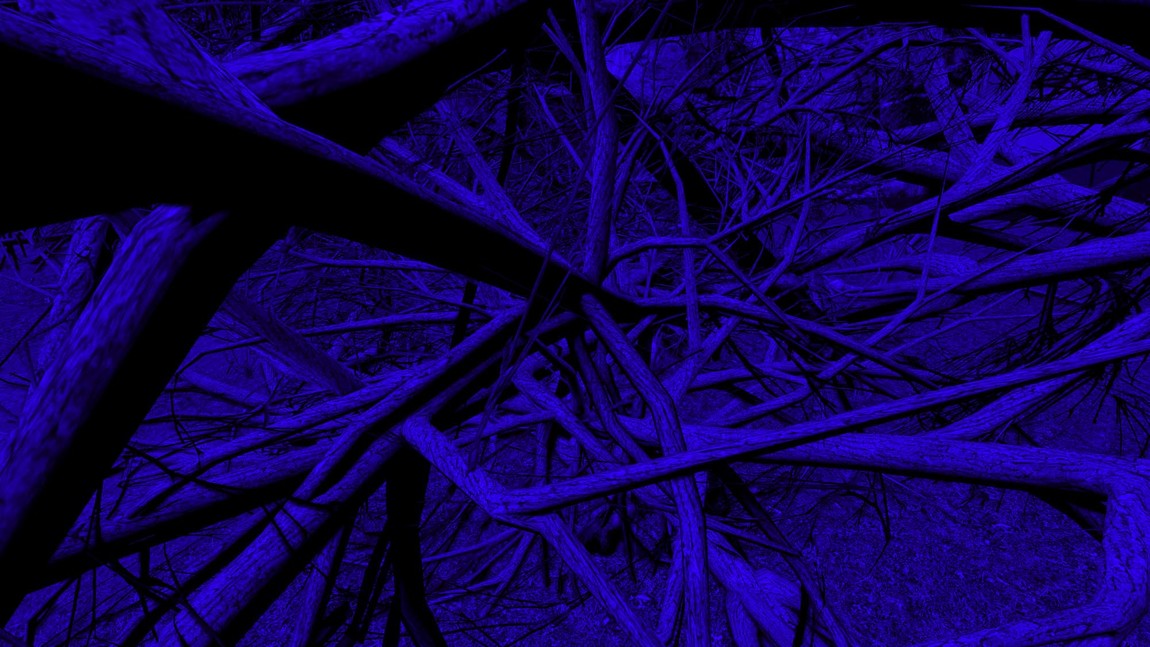

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding The Outlands (detail, still) 2011. Interactive digital projection, bespoke gaming software, computer, controllers, twigs, table. Collection of Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney. Anne Landa Award and Contemporary Collection Benefactors 2011

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding Monocline: White Cube 2010. Realtime 3D environment, Unreal Engine, Kinect motion sensor, double HD video resolution with spatial 3D audio. Photos: David Haines

Field recordings and live monitoring of the environment are a recurrent element in the artists’ collaborative work. Over the years Hinterding has constructed a number of purpose-built VLF antennas which can pick up electromagnetic frequencies emanating from the wiring in their house, various electronic devices and the city grid, as well as from further afield, such as lightning strikes and the faint hum of the Milky Way. These live and recorded sounds play a vital role in Haines’ and Hinterding’s art, reflecting a conceptual and material approach that encourages energies to infiltrate the works and the audience’s experience. As part of their MCA exhibition, the artists have released a vinyl LP with field recordings and soundscapes they have made and performed over the past 15 years.

The sensation of being swept up in an uncontrollable force is a recurring theme in Haines’ and Hinterding’s early collaborations, whether this was an anti-gravitational pull passing over your house and dispersing your possessions, as in The Blinds and the Shutters; a paranormal energy that made logs float, as in The Levitation Grounds; or an unstoppable deluge with the potential to engulf everything, as in House II: The Artesian Basin Pennsylvania USA (2003). In House II, the last work the artists created while living on the Coogee coast, the sea’s relentless current surges onto a suburban street through the front door and windows of a spooky gothic mansion. It is unclear whether the gushing water is the result of a supernatural occurrence inside the haunted-looking house, its whitewashed portico equipped with an ominously large satellite dish, or some environmental catastrophe erupting underneath. The latter seems more probable, especially taking into account humanity’s record for such events17 and the implication that the Great Artesian Basin, the increasingly vulnerable fresh water source underneath Australia,18 is flooding the USA. In front of the house, the endless torrent floods the screen, suggesting that it is only a matter of time until everything is swept underwater. In contrast to the cinemascope view of the ocean and its wild weather at Coogee, the outlook from the artists’ current ground-floor studio in the Blue Mountains19 is much finer in grain, and the nature they can see is a lot closer up. While one can find views of majestic ranges very close to this home in the mountains, it is also the intense and varied greenery of the 35-year-old European-style garden just outside their windows and the Australian bush beyond that sparks their imagination.

Looking at the work the artists have produced since moving to the mountains, it is apparent they are going deeper into both the landscape and the cosmos. Haines has produced a number of works focusing intimately on plants. In A disassembled flower (2012) he deconstructed a synthetic aroma formula for jasmine into seven aroma accords,20 infusing each into a cardboard geodesic sphere for the audience to smell. An eighth sphere contained the recombination of all seven components, recreating the fragrance of synthetic jasmine. The artist’s sketchbook illustrating these complex molecular calculations are displayed as UltraChrome prints on the MCA gallery wall. In The Phantom Leaves 1-5 (2010), five synthetic herbaceous fragrances he had composed in his aroma studio – Mint Glass, Wormwood of the Sea, Violets on Fire, Grass Valley and A Thousand Leaves – were presented in vials alongside images of local plant specimens that were subjected to a process of high-voltage electrophotography. The photographs were created using a home-made Kirlian camera Haines constructed after walking around the garden and recalling the glowing images of plant auras his mother had shown him in the 1970s.21 In The Wollemi Kirlians (2014), 24 electrostatic photographs of different plant specimens he had collected from the Wollemi Ranges glow with radioactive-like luminescence, their delicate edges surrounded by fields of radiant blue, violet, pink and purple. Tiny sparks of electricity sizzle in the negative space around the plant varieties, forming electrified auras that seem to verify their energetic presence in the world.

Wollemi National Park holds a special fascination for many Australians as it is home to the fabled Wollemi pine, a primordial species of tree that grew in the days of the dinosaurs and has miraculously survived into modernity, hidden in a still undisclosed location deep in the Blue Mountains’ wilderness. Incredibly, parts of this precious wilderness are in constant danger of being polluted by nearby mines, something the artists have become vocal opponents of. Intended to be placed alongside the grid of framed Kirlian photographs, two lumps of coal sit on the green perspex surfaces of matching wooden tables. This installation, entitled Slow Fast Mountains (earth aroma) (2014), comments on both the incredible speed of today’s mining practices and the almost inconceivable time it takes for the sun’s energy, stored in ancient plants underground, to form into coal. Steeped in a pungent fragrance composed from geosmin, pyrazine and vetiver, the coal’s aroma permeates the gallery with a wet, green, earthy smell.

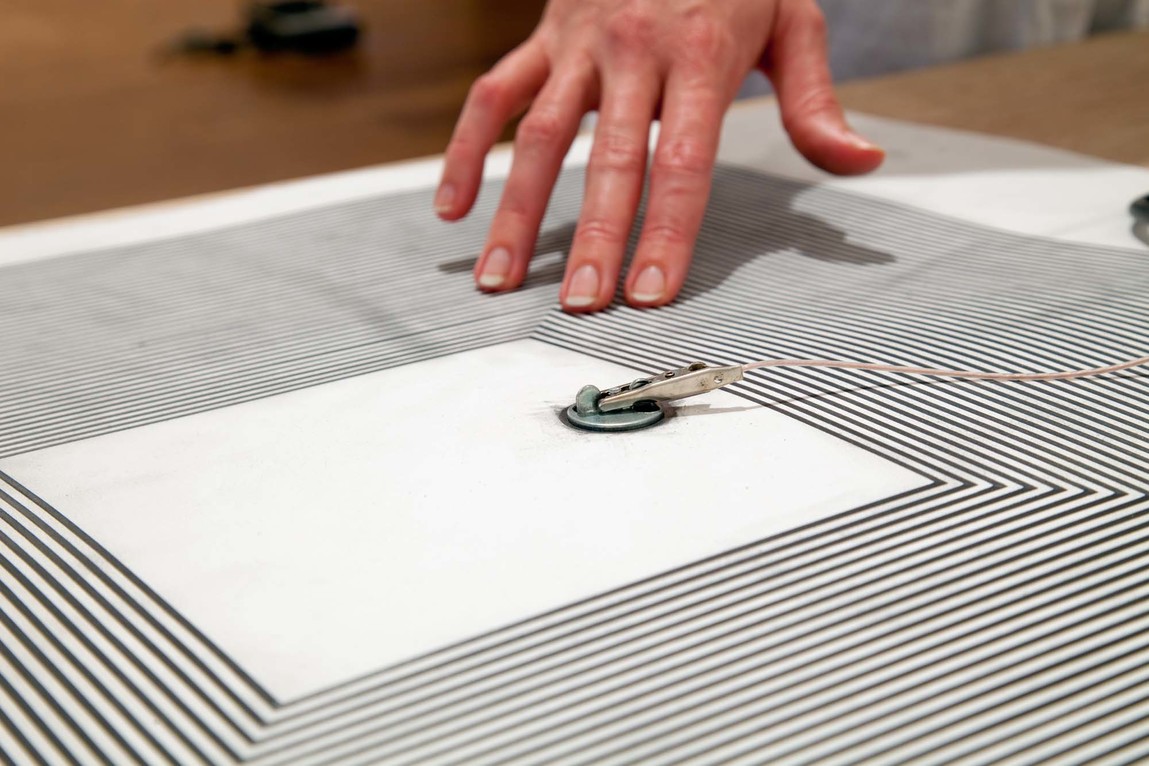

Reflecting the complexity of their surroundings, many of the artists’ recent works move between micro- and macroscopic views of the landscape. These works focus on the mathematical world of fractals that exists both inside the computer algorithms used to make naturalistic scenes in 3D game worlds and in the formations of plants growing just outside their windows. As Hinterding explains, ‘our garden and its highly complex, fractal structure has made its way into our work.’ Hinterding’s recent investigations have led to her to create a number of drawings and stencils referencing early experiments in fractal mathematics. These extraordinary 2D structures are made using graphite on paper, or are stencilled onto glass or perspex. They build on her earlier works, such as The Oscillators (1995), a series of functioning graphite and silver leaf drawings of a phase shift oscillator circuit diagram.22 In later works, such as the Aura (2009/15) and Sound Wave Induction Drawing (2012) series, Hinterding creates graphite drawings that also function as graphic antennas. These works resonate sympathetically with electromagnetic fields within their environment and are often connected to a sound system so we can hear this microscopic activity taking place. Like The Oscillators, her more recent drawings also function as open circuits and respond when people touch them, due to the electrical conductance of our skin. Hinterding utilises these conductive properties within our bodies and her drawings to create unexpected sensory experiences, allowing us to ‘play’ the works like musical instruments and generate different sounds through pressure and movement. For each series of works on paper left uncovered during the exhibition period, a set of ‘Dirty Drawings’ is created. These smudged and smeared drawings document the human interactions and their temporal dynamics.

Joyce Hinterding Ulam VLF loop (graphite) 2009. Graphite, custom leads, mixer, headphones, ultrasonic speaker. Photo: Andrew Curtis

Fractal mathematics is crucial in antenna design as it allows a very long line to be compacted into a very small space.23 This is something that resonates powerfully within Hinterding’s solo work, but Haines explains that it is also central to contemporary cinema. As he points out, it is the fractal mathematics within special effects technologies that mobilises cinematic space, opening it up to new imaginary compositions. While the aesthetic beauty and mysterious power of simple fractals is seen in Hinterding’s early graphic antenna drawings, Haines’ and Hinterding’s recent collaborative work Geology (2015) uses substantially more complex fractal mathematics to create convincing simulations of the ‘natural’ world. Expanding on their earlier interactive screen-based works Monocline White Cube/Black Boxes (2010) and The Outlands (2011), Geology utilises a computer game engine to create a virtual world that the audience can explore.24 The artists describe Geology as a ‘speculative geography where the imaginary is placed on the same footing as information from day to day reality’. Inspired by a research trip they made to the badly damaged Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna O Waiwhetū in New Zealand after the devastating Christchurch earthquake of 2011, it is an investigation of ‘how culture interacts with chaotic forces’.25

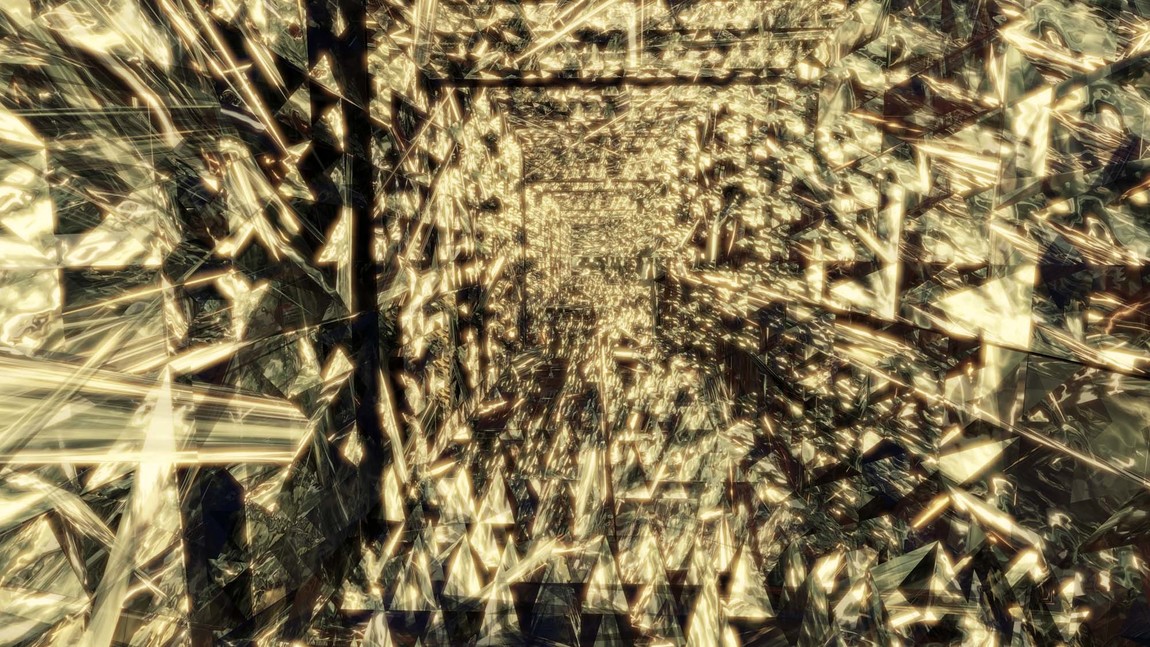

Projected at over 16 metres wide in 4K resolution in one of the MCA’s double-height galleries, Geology is an amplified cinematic experience. Its imaginary terrain has three distinct levels to explore, each one taking the audience deeper underground to discover hidden arcane energies. The first level is a seemingly endless rocky landscape, an immense vista flooded with golden light that we float across like spy drones over Afghanistan. We can control our trajectory across this territory by moving our bodies in subtle ways; then at certain points we find ourselves zapped into the next level. Upon leaving the golden world we enter a dystopian built environment filled with abandoned buildings, grey concrete bunkers and museum-like white cubes. Like the earthquake-damaged gallery in Christchurch, these architectures are filled with cracks and voids that we soon discover are portals into the final level, a psychedelic underground world of energy, sound and vibration. Like the sparkling crystalline caverns in The Outlands (2011), these sharp, glittering structures are made by extending fractal shapes in a computer program until they digitally explode.

Haines has been rock-climbing since he was very young. Since moving to the Blue Mountains, both artists have become avid bushwalkers and canyoners, spending many days at a time exploring the ranges near their home, as well as travelling further afield to experience other wild and remote places. With a longstanding interest in maps and cartography, Haines has made a number of works that engage in a process of naming sites in imaginary landscapes. He sees these as being closely related to the works he has made using 3D game technologies; as he puts it, ‘map makers are inventors of simulated worlds’. In his photographic work Noumenon Ranges (2013), a realistic-looking yet algorithmically generated terrain is mapped using place names partly derived from 17th century metaphysics. Through his art, Haines has frequently explored this period, which is associated with the birth of the algorithm and the hyper-detailed depictions of nature known as the Baroque.

Plunging deep into the landscape also has a practical purpose for Haines and Hinterding as it allows them to experience aspects of the natural world that are central to their work but are hidden in the suburbs and the city. It is at the bottom of a ravine that they can see entropy and energy dispersion in action, in the relationship between large rocks on the cliffs overhead and grains of sand on the riverbed. They can also hear the sounds of natural radio. Just as ambient light from the city blocks our view of the stars and it is only by getting into nature that you can clearly see the Milky Way, it is also only by moving away from the all-pervasive hum of the city’s electrical grid that you can pick up strong VLF signals from beyond the terrestrial world. But it is not only deep in the bush that the artists find themselves awash in electromagnetic signals; these cosmic energies can also be found much closer to home.

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding The Outlands (still) 2011. Interactive digital projection, bespoke gaming software, computer, controllers, twigs, table. Collection of Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney. Anne Landa Award and Contemporary Collection Benefactors 2011

'The strange thing about television is that it doesn’t tell you everything. It shows you everything about life on Earth, but the true mysteries remain. Perhaps it’s in the nature of television. Just waves in space.'

David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth

When rain falls from the sky we can see it falling, we can hear it hitting the earth, smell it on the ground and feel its cool wetness on our skin. Cosmic rays and charged particles also shower the earth, but our senses alone are not enough to perceive them.26 These days nearly everyone lives in a turbulent sea of electromagnetic radiation; its waves are all around us. This is true even for Haines and Hinterding living in the Blue Mountains, where all the wires in their house, as well as nearby power lines, generate their own electromagnetic fields. In the video work Encounter with the Halo Field (2009/15), the artists perform a strange dance holding fluorescent tube lights under the electrical transmission towers adjacent to their home. As they approach the steel lattice structures, the hum of electrical energy can be heard around them and the tubes illuminate in the darkness.

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding Purple Rain (detail, still) 2004. Photo: Michael Myers

In everyday life we are used to electricity coming out of ‘holes’ in the wall and powering our appliances only when we plug them in. The unexpected illumination of the tubes in the artists’ hands works against this everyday understanding of electricity, suggesting a mysterious event has taken place, one in which power is magically transmitted through the air. The scientific explanation behind the phenomenon would seem to be that the strong electrical field from the transmission towers comes into contact with the lights, exciting atoms of mercury gas inside and triggering them to emit ultraviolet light that then strikes the tube’s phosphor coating, making them glow. Rather than explaining this spectacle, Encounter with the Halo Field plays with the knowledge that electricity is all around us. With its intermingling of field recordings with dance and supernatural imaginings, it reminds us that this energy is much more spirited than the unthinking routine of switching things on and off in our homes would suggest.

Purple Rain (2004), is another work that draws attention to the dynamics of the everyday electromagnetic ecology, in this case relating the power of television to one of nature’s most formidable forces, the might of an avalanche. A significant work in the history of Australian video art, Purple Rain opens up video aesthetics to the hidden world of the live broadcast signal. In the installation, four TVs are turned to face away from us so that all we can see is the cool glow of their displays reflected on the gallery wall. A large video projection in the same space flickers erratically between scenes of snow plummeting down a huge mountain and a field of purple TV ‘snow’ or static. The four TVs are connected to four TV antennas hung from the ceiling that are tuned to pick up live television signals just as they would on the roof of a suburban home. The signals trigger the video images, while also being redirected through an audio-mixer to create an electronic noise-scape that fills the room with loud glitches, throbbing drones and hums.

One way of conceptualising the relationship between the avalanche and the static in Purple Rain is that both images are related to a visual language of disturbance. TV snow usually signifies an electromagnetic disturbance in the atmosphere being picked up by an antenna, and is generally something we associate with technology rather than the natural world; an avalanche epitomises what we think of as a disturbance in the natural order. In the topsy-turvy world of Purple Rain, however, the avalanche on screen is a simulation, a digitally composited image triggered by the natural forces used to transmit broadcast television. This live signal remix of real and simulated, and environmental and technological, disturbances poses the question of whether there is any distinction between the so-called natural world and the world of our invention.27 Hinterding, who has been interested for some time in discovering ways to scavenge television’s surplus energy, comments that ‘we forget how powerful broadcast television is … and how many kilowatts of power are coming through the air.’ As she points out, this electrical power is combined with the social and political charge of media images, which ‘come to us with a huge force … changing the world.’28

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding EarthStar 2008. Photo: Michael Myers

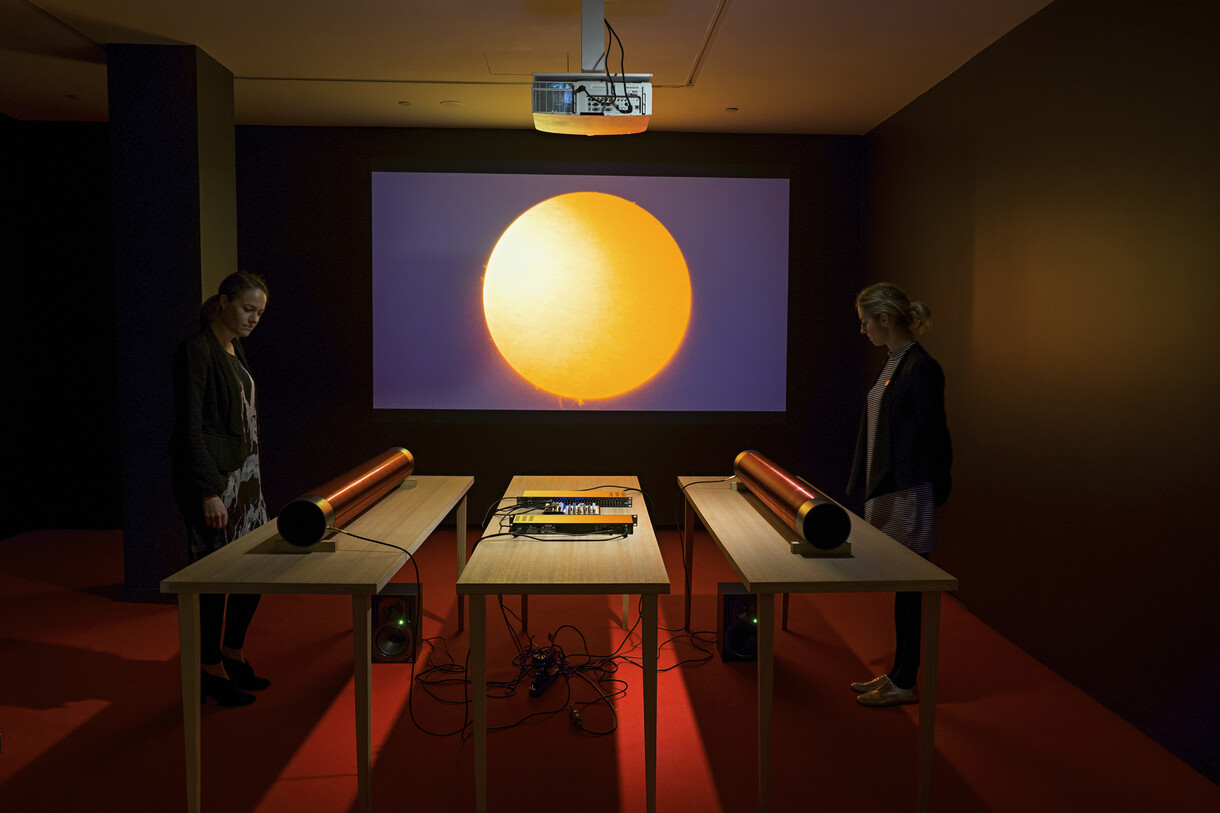

Moving beyond the local electromagnetic sphere, EarthStar (2008) rockets us into outer space, enticing viewers to take a multisensory journey to the sun. Resembling an eccentric museum filled with relics from an impossible solar voyage, the installation presents objects and ethereal phenomena that offer ways to experience the brilliant celestial orb outside of the visible spectrum. Most recognisable is a large projected video of the sun’s turbulent solar winds and flares that transforms slowly from a sphere of golden light to a black eclipse with an explosive red border. The artists captured these spectacular images by attaching the lens of a hydrogen-alpha telescope to a camera. Unlike looking at the sun directly, where its damaging rays will blast finer details from view, this system can capture detailed images of the solar chromosphere just above its surface.29 The solar images are accompanied by two gleaming electromagnetic antennas made from lengths of copper wire wound neatly around cylindrical graphite coated tubes. Positioned on tables, the antennas are tuned to pick up the sun’s electromagnetic radiations, irregular radio bursts that are amplified to create a live solar soundtrack that fills the room with sizzling crackles and the occasional pop.30

Adding to this multisensory solar experience, two synthetic fragrances are held in small refrigeration units and electric-blue glass jars at the side of the room. Created by Haines in his aroma studio, Ozone One: Ionisation and Ozone Two: Terrestrial imagine the smell of the sun, or, more precisely, the smells that might emerge from the sun’s interaction with other things. The most emotive of all the senses, smell can transport you to forgotten times and places, as well as deep into human consciousness, evoking ancient yearnings and sensations. Haines hints at these possible journeys with evocative phrases such as ‘lightning strike’, ‘burnt electrical wire’, ‘summer rain’, ‘dry lake bed’ and ‘lunar rock’ on small printed labels. This affecting compendium of smelt and imagined odours intermingles in the installation with the sounds of the sun’s electromagnetic emissions vibrating through the copper antennas and the extraordinary images of solar flares and winds. Rather than illuminating scientific facts about the sun, EarthStar immerses us in a sensory imagining of our elemental connection to this blazing life force.

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding, Cloudbuster on site at Mt Wilson. Photo: Michael Myers

'Reich’s gift is to make us think again about the apparent givens of natural forces, energy fields and how the world is assembled.'

Artists’ statement, Two Works for Wilhelm Reich (2006)

The sun is not the only energetic life force that has inspired Haines’ and Hinterding’s work. They have also delved into the more speculative realm of orgone energy, a concept put forward in the 1930s by controversial German psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. According to Reich, orgone energy is the primary life force, pulsating through the libidinal body, the atmosphere and the cosmos.31 For Haines and Hinterding, Reich’s eccentric theories are an ongoing reference point in their work; they describe him as ‘the great 20th century explorer of the inner depths of the psyche and the invisible in nature’.32 For them, Reich’s radical interdisciplinary thinking and his merging of imaginary and factual realms are an inspirational catalyst for their art-making:

In The Black Ray (2011-12), and Starlight Driver (2011–12), Haines and Hinterding follow Reich’s instructions for building a cloudbuster, a device he claimed could channel orgone energy and change the weather. Tall and rather menacing structures, the artists’ sculptures resemble a cross between a telescope and ray gun from a science fiction film. Made of thin anodised aluminium tubes, irrigation piping and a water pump, they embody an energetic potential, as if waiting to be switched on so they can unleash their mystical power into the sky. The sculptures are accompanied by a print of Reich’s instructions for using the cloudbuster and his warnings about their potentially dangerous consequences. The artists say playfully that they are hesitant to use the ‘working’ apparatuses in any actual environmental contexts. Instead the objects have become symbolic in their practice – metaphorical ‘ether rods’ that can gather and transmit ideas and both supernatural and electromagnetic energy.33

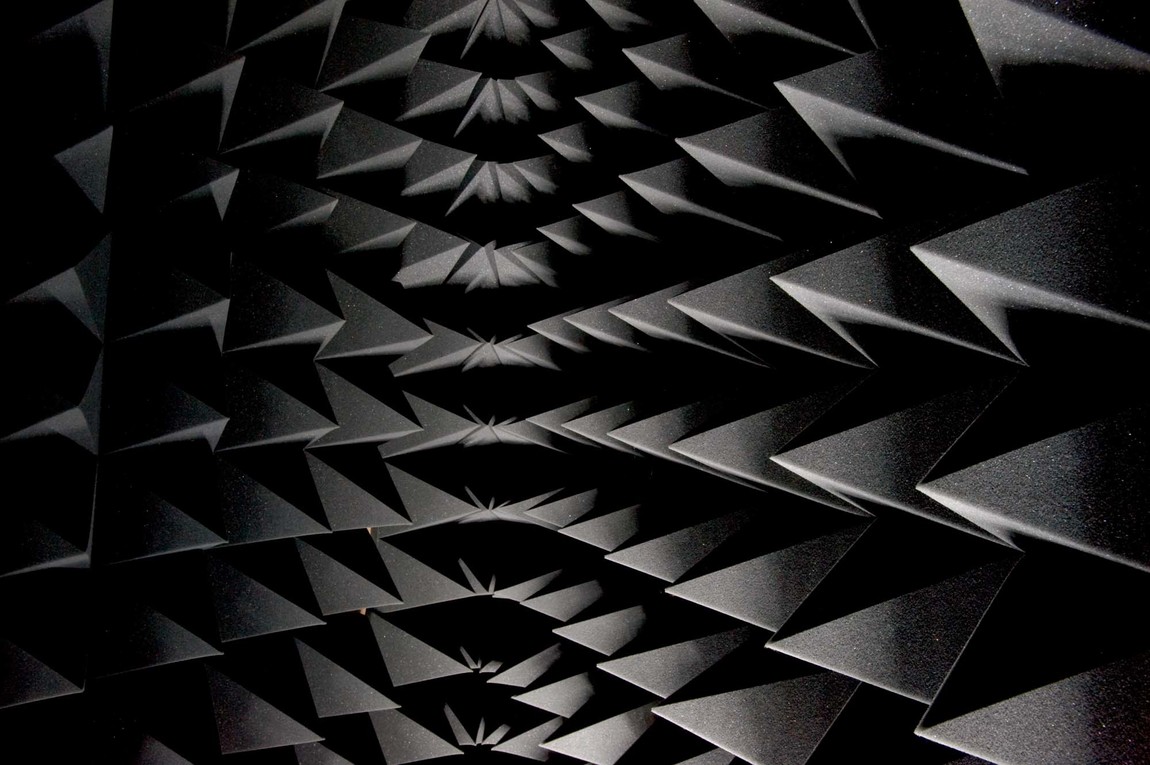

Before the cloudbuster, Reich’s most famous invention was an unusual chamber called the orgone accumulator, a large wooden box lined with metal and other insulating material which, he claimed, could charge up people’s bodies with orgone energy and improve their health.34 Orgone accumulators, which became very popular within artistic and literary circles in the 1950s, were designed so that the energy field of the device would make contact with the energy field of the user, exciting each other and creating an even stronger charge.35 In Haines’ and Hinterding’s largest sculptural work to date, Telepathy (2008/15), they invite us to enter a different kind of energy enclosure. Instead of attracting orgone energy, Telepathy is an anechoic (or echoless) chamber, designed to absorb sound waves and electromagnetic radiation while also insulating its occupants from exterior noise. The bright yellow triangular sculpture is an extremely heavy structure made of wood, metal and hidden layers of black rubber. Its futuristic interior is lined with rubberised foam tiles, spiky pyramid-shaped objects that create an alien backdrop for what is essentially an inward journey into the echoes of body and mind. One of Haines’ favourite films is in fact Nicholas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth. Starring David Bowie, it is about an alien who sets up a multi-million-dollar technology company in order to make enough money to send water back to his drought-stricken planet. Bowie’s spacecraft in the film is an anechoic chamber, its high-tech interior evoking the unknown qualities of alien machinery that could eventually take him home.

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding Telepathy (detail) 2008/15

The architecture of Telepathy questions the notion of home as a safe haven designed to shield us from outside forces. While most homes in Australia today are bristling with technologies and their attendant lights, sounds and radiations, Telepathy’s interior is a place where you can be alone with your thoughts, where your mobile phone won’t pick up a signal and where the influences of the external world slowly withdraw. Both comforting and disturbing, it becomes a place to reflect on the ‘subtle energies’ of the body.36 For Haines and Hinterding, while Telepathy is deeply connected to all their projects, it is also intrinsically different, blocking energy when all their other works gather it.37

It is this continued engagement with energetic forces that lies at the heart of Haines’ and Hinterding’s collaborative practice. Inspired by the poetics of real and imaginary phenomena, they eagerly travel along the often esoteric paths their artistic investigations lead them on. Summoning the affective power of electromagnetic waves, light, smell, sound and vibration, and delving into the mysteries of the supernatural, through their works, they encourage us to marvel at the wonders of the universe, but also to reimagine the everyday world as a place buzzing with invisible energies, curiosities and sensations.

This essay was first published in Anna Davis and Doug Kahn, Energies: Haines & Hinterding, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2015. It is reproduced on this website with kind permission.