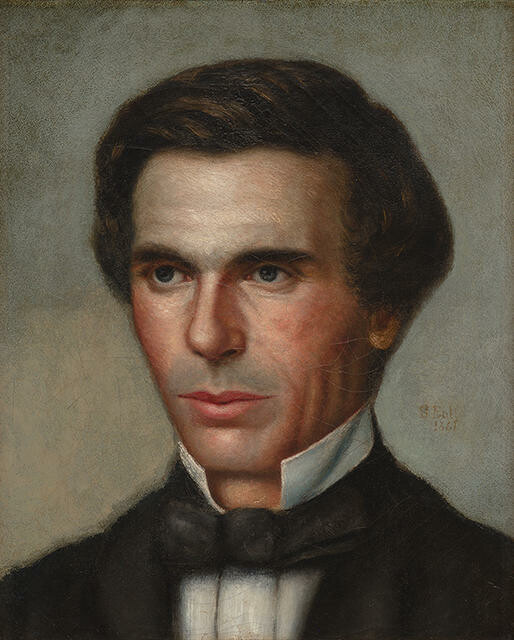

Mary Donald John Robert Godley (detail) 1852. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, transferred from Banks Peninsula District Council 2006

Such Human Tide

The exhibition He Waka Eke Noa brings together colonial-era, mainly Māori, portraiture alongside objects linked to colonisation – it’s a predictably uncomfortable mix. While the degree of discomfort may depend on one’s background or degree of connection to an enduringly difficult past, objects related to emigration and colonisation can be a useful lenses. As relics from a specific period in global history, when the movement of (particularly) European people was happening at an unprecedented scale, they hold stories with a measure of complexity that obliges an open-minded reading. There is no denying that they speak of losses and gains, of injustices and rewards.

From a cold Lyttelton winter on 29 July 1851, Charlotte Godley – wife of John Robert Godley, founder of the new Canterbury province – wrote to her mother in Wales of weather that was ‘still very wet, and very unfavourable for slipping about in the dark, up and down these muddy hills.’ In her next few lines she described ‘a much deeper and pleasanter excitement, in watching a portrait of Arthur growing under the skilful hands of Miss M. Townsend, who has been staying with us to that end… It seems she used to take portraits professionally, in London; but she did not expect to be asked for such things here.’1 A few days later, Charlotte appraised the completed portrait of their four-year-old son ‘a very pretty picture, and I am going to get her … to do another of my husband, for Miss Townsend only asks three or five guineas, and we are glad to give her something to do…’2

Mary Townsend was among the influx of recent arrivals, having reached Lyttelton aboard the Cressy on 27 December 1850 with her parents James and Alicia Townsend, five sisters, four brothers and a cousin. Eleven months later, she married the appointed ‘Colonial Surgeon at Lyttelton’, Dr William Donald, who in September 1852 made a gift of this portrait to the recently launched Lyttelton Colonists’ Society, as a likeness of their chairman – the portrait evidently initiated by Charlotte. Following the presentation came Godley’s ‘promised lecture on the early colonization of New Zealand’, as the Lyttelton Times reported, commenting also that ‘there are but few Colonists, we apprehend, who possess other than a very limited knowledge of their adopted country.’3

Mary Donald John Robert Godley 1852. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, transferred from Banks Peninsula District Council 2006

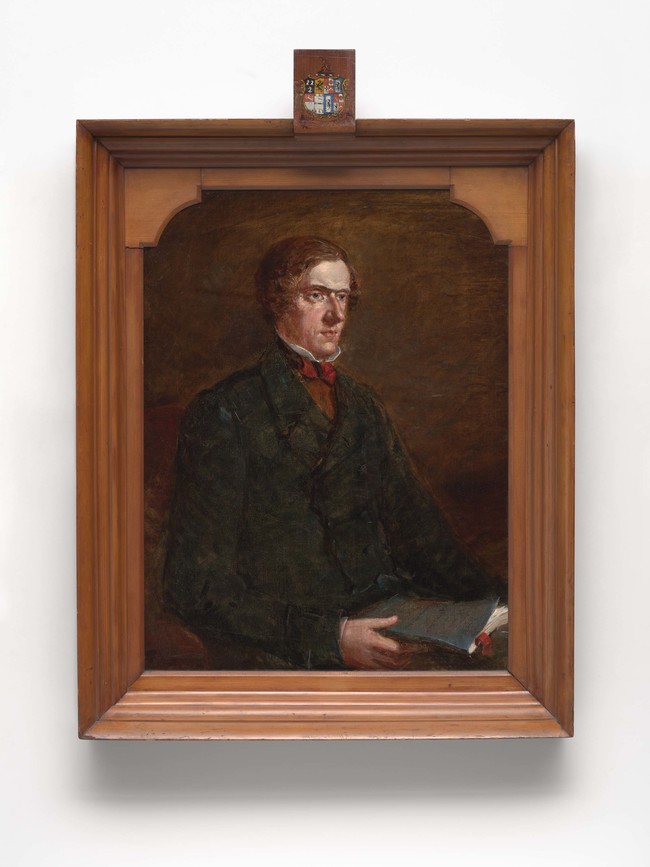

Herbert Bourne (after Ford Madox Brown) The Last of England 1852–5. Engraving. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

At almost the exact same time in London, the painter Ford Madox Brown (1820–1893) was starting an ambitious work on the theme of emigration, inspired by the actions of a friend. Madox Brown, with William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, had recently farewelled their fellow Pre-Raphaelite brother Thomas Woolner – the sculptor who would later create Christchurch Cathedral Square’s memorial statue of John Robert Godley.

Woolner’s departure for the Australian goldfields on 24 July 1852 was a spark for Madox Brown’s The Last of England, a large oil composition of an emigrant couple; a contemporary Flight into Egypt with a British family entering the unknown. The painting pictured an increasingly familiar scenario, with vast numbers at this time entering foreign territory in pursuit of a better life. Most were bound for America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand or South Africa.

Madox Brown modelled the couple on himself and his partner Emma Hill. The painting took three years to complete, during which time their partnership and eldest child Katty (born 1850) were legitimised in marriage (in 1853), and a second child, Oliver was born (in 1855). Katty appeared at rear left, while Oliver was just visible as the tiny hand held by Emma’s. Woolner’s story also changed in this time. He returned to London in October 1854 before the painting was even finished: unsuccessful at mining, he had also been disillusioned by the coarse realities of colonial frontier Sydney life.

(Herbert Bourne’s exquisite black and white steel engraving of The Last of England, published in London in 1870, must stand in for the original, which remains in Birmingham.)

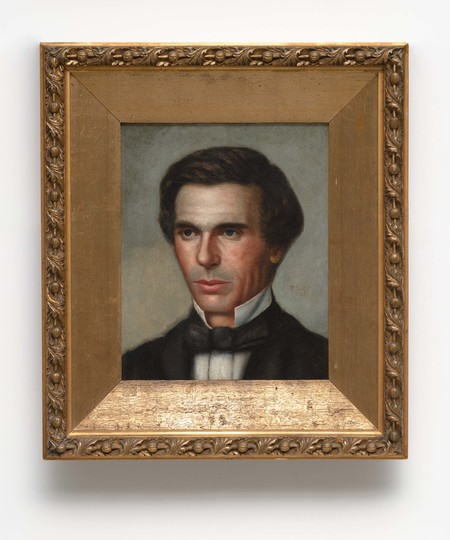

Samuel Butler Portrait of John Marshman 1861. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1996

25-year-old Samuel Butler reached Lyttelton from England in January 1860, and in his four and a half years here doubled his capital as a sheep farmer in high-country Canterbury. From his remote station in the Upper Rangitata, he also started writing Erewhon; or, Over the Range – the fantastical novel that would establish his literary reputation. His regular visits to Christchurch included receiving hospitality from this portrait’s subject, John Parker Marshman, and his wife Caroline. Butler is said to have ‘played on the Marshman piano, painted in the dining-room, and walked in the Marshman garden.’4 He made this portrait in 1861, the year before Marshman left Christchurch to become Canterbury Province Emigration Agent in London.

John Marshman was a 24-year-old surveyor from Bristol when he first reached New Zealand in 1848, and was set to work in Wellington recording damage from recent earthquakes. Under Captain Joseph Thomas, he also did surveying for the Ngauranga Gorge and the Canterbury Province, its location selected in April 1849 by Captain Thomas on vast tracts of land purchased in 1848 from Ngāi Tahu by the New Zealand Company through the notorious Kemp Deed.

Marshman embraced opportunity and employment with Canterbury’s Provincial Government, settling at first in Lyttelton. A close friend of Godley, his earliest roles included provincial treasurer, auditor and ‘Registrar of Brands for Sheep’. He also started farming on the Lincoln Road near the Wilderness Road (later Barrington Street) and at Mount Grey, and became a thoroughly experienced colonist.

Marshman published two books for prospective settlers in Canterbury, in 1862 and 1864. While his role as emigration agent involved screening the suitability of settlers and overseeing the outfitting and construction of emigrant ships, his books advised on the essentials of settler life, including what to bring or leave behind. In recommending ‘What Sort of People ought to Emigrate’, he also dealt with ‘Discontent among New Comers’, ‘Description of Men who may count with certainty upon obtaining Employment’, and ‘Single Women, what description most needed’. Assisted passage was ‘restricted almost entirely to Agricultural Workmen, Shepherds, and Women Servants’.5

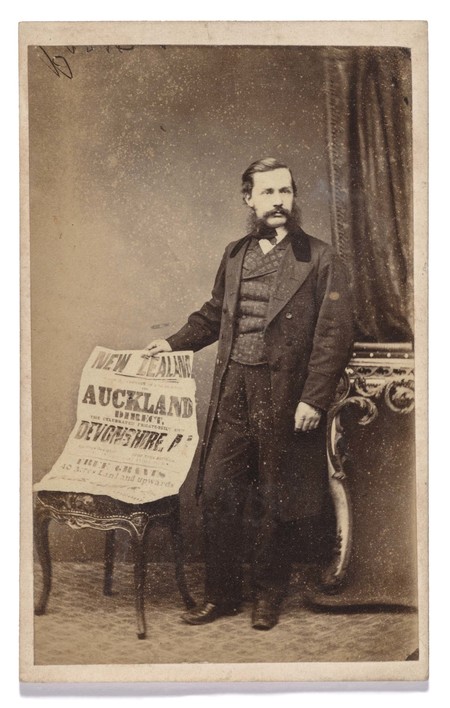

The London School of Photography Edward Brendon Parsons (c.1835–1915) 1862. Carte-de-visite albumen photograph. Private collection

In 1862, facing his imminent departure for New Zealand, the London wholesaler’s clerk Edward Brendon Parsons chose to commemorate the moment by visiting a nearby photographic portrait studio with the voyage’s publicity poster in hand. Under 24-year-old Captain Holt, the Devonshire sailed on 29 October with ‘a very large cargo and a number of passengers, amongst whom [were] several officers to join their regiments and non-commissioned officers in charge of telegraphic apparatus sent out by Government.’6 There was both war and a push for new settlers in New Zealand.

A stormy fifteen-week voyage to Auckland delivered 154 live passengers (two had died), including: '1 architect, 2 brewers, 1 grocer, 22 farmers, 1 nursemaid, 1 plumber, 1 surgeon, 3 clerks, 6 servants, 18 labourers, 1 butcher, 1 engineer, 7 farm servants, 1 shepherd, 1 baker, 1 iron moulder, 2 carpenters, 1 shopman, 1 draper, 1 iron founder, 1 shipwright, [and] 1 mariner’, along with ‘three splendid Leicester ewes and two rams…'7

Disregarding the poster’s promised ‘Free Grants 40 Acres Land and Upwards’ in Auckland Province, Parsons moved instead to Dunedin, where the Otago gold rush was underway, and entered into business with his future brother-in-law as a Princes Street grocer and tea merchant. In 1863, he married Mary Arthur, daughter of Carpenter Arthur, a Cornish-born coal and timber merchant turned Auckland land agent. After relocating to Auckland, in 1868 Parsons became the secretary for the newly-established Auckland Gas Company, which produced gas for street lamps, gas-powered engines and stoves throughout the city. Parsons remained with the company for forty-one years, and became known as the company’s ‘indefatigable secretary … happy to furnish every information in his power to anyone who may desire it.’8 He retired in 1909 and spent the last few years of his life in Japan, where he died in 1915.

(NB: This photograph is not included in the initial version of He Waka Eke Noa, but may be included at a later stage of the exhibition.)

Laura Herford The little emigrant 1868. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Suter Art Gallery, Nelson. Donated by Marjorie Sheat 2007. Acc. No. 1027

In July 1860, Laura Herford (1831–1870) became the first female artist to be accepted into the London Royal Academy Schools, after shrewdly submitted drawings signed with her initials instead of her name. Her success occurred after a determined group campaign for women’s admittance into the Royal Academy, and became a watershed for many others.9

Four years later, Laura left England for New Zealand upon learning that her brother, Adelaide solicitor Walter Vernon Herford, had been seriously injured there. Finding himself in financial dire straits, with an appearance in 1863 in the South Australian insolvency courts, Walter had signed up for three years’ military service in the Waikato, New Zealand, after which time he would be granted 300 acres of land there: this he assigned in advance for repaying creditors.10 Major Walter Vernon Herford of the 3rd Waikato Regiment Militia thereby became part of Governor George Grey’s plan to extinguish the Māori Kingitanga movement. On 2 April, while he was leading a charge against the Kingites at Ōrākau, a bullet entered his skull and he became in need of urgent care.

Laura arrived in New Zealand in January 1865 to discover that Walter had died three months after being injured, even before she had left England. She spent three months in New Zealand, mostly with the Nelson surveyor Thomas Thompson and his wife Sarah, whose account of leaving Leeds as a young emigrant in 1841 inspired this painting: ‘She recounted how she often sat by the bulwarks looking out over the “wide, wide sea dreaming of home…”’11 The evocative study was later shipped to New Zealand in a piano that Herford purchased in London on Mr. Thompson’s behalf.

![Nelson King Cherrill Jane [Heni Tuia] and Elizabeth Macpherson 1879. Carte-de-visite albumen photograph. Collection of Antony G. Rackstraw](/media/cache/46/c4/46c4858f0fe49293dec36e6ce86dacf1.jpg)

Nelson King Cherrill Jane [Heni Tuia] and Elizabeth Macpherson 1879. Carte-de-visite albumen photograph. Collection of Antony G. Rackstraw

Jane (1874–1909) and Elizabeth Macpherson (1872–1907) visited Nelson Cherrill’s photographic establishment in Cashel Street with their Christchurch cousins during a family visit south in 1879. The girls’ father John Drummond Macpherson (1833–1887) was a Scottish-born storekeeper and publican in Matata, Bay of Plenty. His elder brother in Christchurch, James Drummond Macpherson, was a Fendalton merchant, customs agent and local manager of the South British Insurance Company.

The venturesome John had been a mercantile clerk in Greenock before leaving Scotland in the early 1850s for the Californian goldfields. He later served with the California State Militia during the Indian Wars.12 By the late 1860s he was working as a seaman in Australasian waters, but by 1870 he was settled and living in Matata, where he married the Mokoia, Rotorua-born Mariana Te Oha (1852–1931); they had six daughters and two sons.

The photographer Nelson King Cherrill arrived in Lyttelton from England with his wife and young family in 1876. He had won photographic prizes in Cornwall, London and Paris between 1867 and 1875 and numerous others in partnership with the (still famous) photographer Henry Peach Robinson; they jointly operated a photographic studio for seven years in Tunbridge Wells, Kent and collaborated on artistic photography projects.

Cherrill opened his new Christchurch studio in December 1876, and in the following year oversaw a photographic display at Canterbury Museum while showing his own ‘art of ceramic enamel photography’.13 In 1879 he claimed to have ‘The only studio in the world where portraits are taken by electricity. The new electric expositing apparatus is the only perfect arrangement for taking children’s portraits.’14 Cherrill left Christchurch for a six-months home visit in 1881, intending to return, but (like the Godleys, Samuel Butler and Laura Herford) he never did.