He Kapuka Oneone – A Handful of Soil

Sarah Hudson The Hill Inside 2023. HD video, sound, colour; duration 10 min. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2023

Our expansive new collection exhibition explores the fundamental role whenua plays in the visual language and identity of Aotearoa New Zealand. Acknowledging Māori as takata whenua, the first peoples to call this land home, themes of kaitiakitaka, colonisation, environmentalism, land use, migration, identity and belonging are considered through collection works, new acquisitions and exciting commissions. Painting, sculpture, ceramics, photography, moving image, printmaking and weaving by historical and contemporary artists are brought together to reveal how land has been a material and subject for art in Aotearoa for hundreds of years. Here, the Gallery’s curators each take a closer look at a key work from the exhibition that tells us something about our complex relationship with the whenua.

Natalie Robertson The Blue Slip (Barton’s Gully), from Mangarara Stream 2023. C-type gloss photographic print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased through the Valerie O. Heinz bequest, 2024

The Blue Slip (Barton’s Gully), from Mangarara Stream

In the Waiorongomai Valley, on the upper catchment of the Waiapu River in the east coast region of Te Tairāwhiti Gisborne, a combination of land erosion and climatic change is contributing to the collapse of hillsides into the river. The source of the flow of sediment downstream into the Tapuaeroa, then Waiapu rivers and out to the ocean is at its most clearly observable from Mangarara, a small tributary that leads into the Waiorongomai River. This ecological catastrophe is the result of over a century of colonial forestry, introduced pests and more recently, sea level rise. The coastal environment has been changed irreversibly, disrupting not only the Waiapu river, but also endemic plants, fish species, and the lives of those who depend on these re- sources. In particular, Ngāti Porou have fished kahawai from this area for generations and can no longer do so.

Photographer Natalie Robertson (Ngāti Porou, Clann Dhònnchaidh) regularly returns to Waiorongomai to witness and document, generating stories about the impact of the ongoing erosion. With a focus on both cultural and environmental relationships, Robertson creates photographs and moving images that explore mātauraka Māori through a whakapapa lens, approaching the landscape as interconnected with atua, tūpuna, tākata, pūrākau and mōteatea. Robertson’s whakapapa to this area escalates her distress regarding the devastation and instils in her work an urgency for action to revitalise and repair.

Parawhenuamea, the atua of alluvial waters, is a maker of land, carrying sediment to the ocean as part of the natural ecological cycle. However, in the case of Mangarara, it is colonial, industrial and economic drivers that have intensified the changes to land and ocean—a situation an Indigenous approach to environmental custodianship could have mitigated, and which may benefit future resource management. Robertson writes:

Indigenous ways of thinking about the intricate interconnectedness of all life on earth and in the atmosphere offer vitally important whole-of-landscape and seascape paradigms that could stimulate creative environmental reinvigoration and reparation internationally.1

Back in 2019, Robertson collaborated with conservation ranger Graeme Atkins and moving image artist Alex Monteith to make the multi-channel video installation Te rerenga pōuri o nga parawhenua ki Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, charting the journey of sediment to Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa the Pacific Ocean and the story of how the extreme coastal erosion impacts the local community—her whānau. For this new work, Robertson has merged several still photographs taken on a medium-format digital camera, producing images of extremely high resolution and sharpness, magnifying and bringing the landscape into detailed focus. Making visible the loss of land, Robertson has come to think of her work as following the form of a mōteatea, a lament, yet she also offers us a sense of hope:

The riverbed rises, river waters rise, sediment settles in the ocean and the ocean rises. So too, must we rise to these challenges.2

Melanie Oliver

Curator

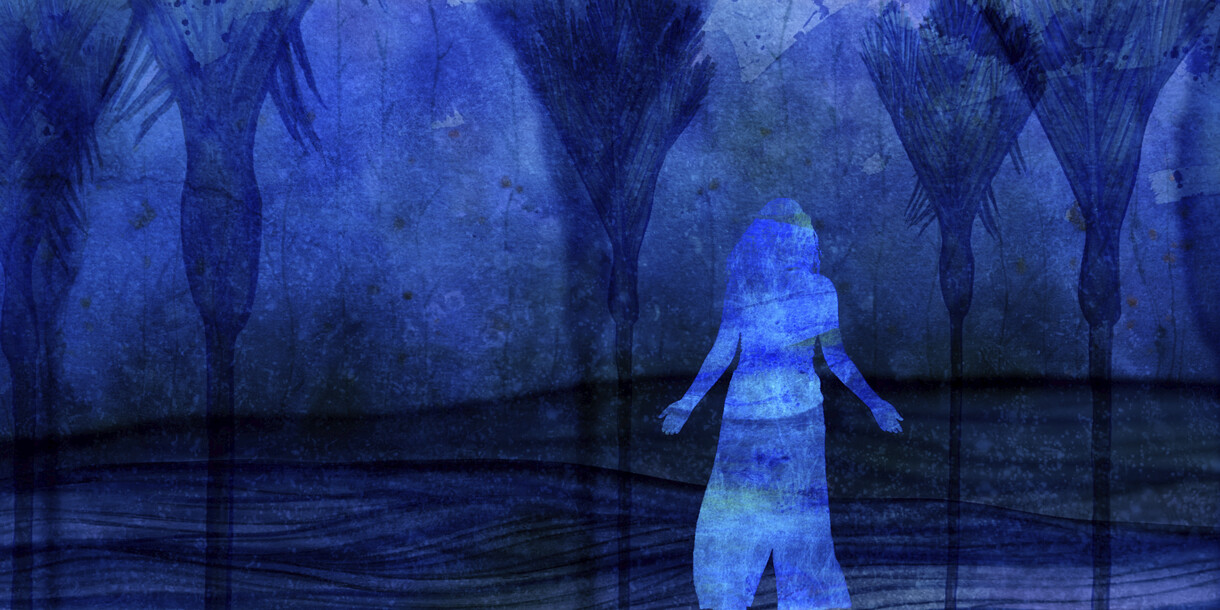

Sarah Hudson The Hill Inside 2023. HD video, sound, colour; duration 10 min. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2023

The Hill Inside

E kore a Parawhenuamea e haere ki te kore a Rakahore.

This meditative two-channel video work by Whakatāne- based artist Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Pūkeko) is informed by the above whakataukī about the interconnectedness of water and rock. Parawhenuamea is the embodiment of water and the parent of silts, sands, and alluvial soils and deposits. Without rock—personified as Rakahore—water does not flow.

This idea has informed many years of research by Hudson into her tūpuna Māori and their use of rocks, clay and soils mixed with water as a material for personal adornment, art making, ceremony and medicine. The Hill Inside is the culmination of Hudson’s research as she explores the whakapapa of whenua, reconnecting with her body and the land through ritual.

The work consists of two separately titled channels. In Reconnect the artist undertakes small rituals of engagement with soil and clay: she applies grey uku to her body, face and hair; she holds rocks and clay in her hands and in her mouth. Water and earth come together to make rich new textures and colours. Remember comprises scenes filmed at the river and includes clay objects that bear marks of Hudson’s rituals.

Initially commissioned by Bundanon Art Museum in Illaroo, Australia for the exhibition The Polyphonic Sea in 2023, The Hill Inside is named for the underground location of the Bundanon Art Museum, and the relationship between earth and the body, particularly for Indigenous peoples. For Māori, the ancestral relationships between people and whenua, mauka and awa are established through whakapapa and often reinforced through the burying of one’s placenta, also named whenua, in the earth.

Chloe Cull

Pouarataki curator Māori

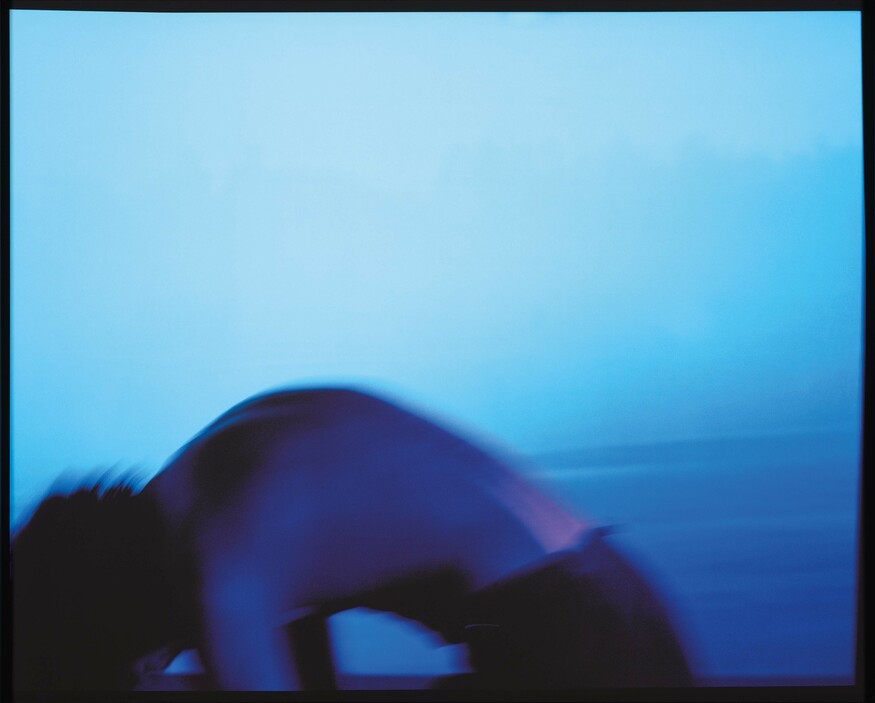

Shannon Te Ao Pūaotanga o te Ao 2022. Archival digital print on Hahnemühle photorag paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2023

Pūaotanga o te Ao

The scene we glimpse in Pūaotanga o te Ao shimmers between worlds and possibilities. Curving forwards, a back morphs into a mountain that might be the artist’s ancestral mauka, Ngāuruhoe. Behind it, a bare wall becomes a half-lit sky. In the hands of Shannon Te Ao (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Wairangi, Ngāti Te Rangiita, Te Pāpaka-a-Maui), the close, personal and ephemeral transforms into some- thing distant, monumental and timeless. He first made this image for an exhibition he called Tīwakawaka after the flitting manu also known as the fantail or pīwakawaka. Well known for its habit of accompanying walkers in Aotearoa New Zealand’s forests, this bird has a special significance in te ao Māori, where it moves effortlessly between realms, passing messages and warnings.

In making this work, Te Ao first created a luminous backdrop from the rear-projected footage of landscapes relating to his whenua and whanauka. He enlisted an actor to perform a range of actions in front of this, which he captured on film. This layered construction lends an appealing indistinctness and fluidity to the resulting photograph. Like many works by Te Ao, it manages to be both specific and expansive—operating in the here and now, but connecting us to the epic and poetic. Though still, it hums with the memory of movement. Though simple, it opens out in many possible directions. Blue is the colour of the sky and the ocean; both vast, endless, and changeable. Here, the shade Te Ao has selected carries with it the suggestion of a particular time and place—the night sky glimpsed from inside a well-lit room. In te reo Māori, te ao can mean world, and pūaotanga is the dawn, so Pūaotanga o te Ao also reads as a beginning of some sort. Whether we interpret that as the creation of the world we currently exist in, or the start of a new one, is left up to us.

Felicity Milburn

Lead curator

Edward Percy Sealy Head of the great Tasman Glacier, with Hochstetter Dome and Mount Darwin, Mount Cook District, March 1869 1869. Albumen print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Corina Silich, 2022

Head of the Great Tasman Glacier with Hochstetter Dome and Mount Darwin, Mount Cook District, March 1869

In 2022, the Gallery received a remarkable gift: a collection of photograph albums and associated material including many letters, created and collated by Edward Percy Sealy (1839–1903), a surveyor and photographer closely associated with explorer, geologist and Canterbury Museum founder Julius von Haast. Sealy was the first to photograph Kā Tiritiri-o-te-Moana the Southern Alps, giving particular attention to unmapped peaks and glaciers on his extensive alpine journeys between 1866 and 1870, sometimes in the company of von Haast.

In April 1867, Sealy made his first trip to the Aoraki Mount Cook District, which included visiting the Mueller and Hooker glaciers and ascending the latter to within one-and-a-half miles of the saddle before crevasses halted his group’s progress. He was joined on this excursion by a trainee assistant named Ball, an unnamed ex-prospector, and a Māori man named Jim, whom he had met at a nearby station and was particularly pleased about having along, noting that “he had been living for some time in the neighbourhood & knew the run of the Country very well”.3 In the same letter to his aunt, he conveyed his utter captivation with glaciers traversed:

Fancy a regular Sea of ice many hundred feet in depth filling up a large valley following its windings like a river and ending with an abrupt face almost a wall from beneath wh[ich] a good sized river is gushing with tremendous force—You must not suppose that all this ice is however clear & visible, on the contrary it pushes before it & carries on its surface an immense mass of debris from the mountains … It is as though an army of a million giants had been engaged ever since the creation in tumbling masses of the mountains, titanic rocks varying in size from a cathedral to an egg down into the valley beneath—Even the very ice seems unable to bear the immense burden laid upon it … as you walk over it constant groans rumblings crackings & reports testify to the internal agitation of the labouring mass.4

Ken Hall

Curator

Rita Angus Wainui, Akaroa 1943. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, N. Barrett bequest collection, purchased 2010

Wainui, Akaroa

Just over an hour’s drive from Ōtautahi Christchurch, on the western side of Akaroa Harbour, Wainui hasn’t changed all that much from when Rita Angus visited in January and February of 1943. A few more baches have appeared over the years but it is still a very laid-back, sleepy settlement; a great spot to unwind and a quiet alternative to the tourist-focused township of Akaroa across the harbour. With little to distract you, apart from wandering along the foreshore or up the hills behind the beach for the stunning views overlooking the harbour, it’s the kind of place where you get into the rhythm of the tides and the land.

Against the disruptive and stressful backdrop of World War II, Wainui was a place of refuge for Angus, a haven where she could shelter from the demands being made on her by the Government’s Industrial Manpower Board to undertake essential war work in a factory—a form of conscription that conflicted with her strong pacifist views. Sticking firmly to her beliefs she became one of the few women in New Zealand to go to court for refusing to work in what were viewed as essential wartime industries.

Wainui provided Angus with an opportunity to step back from the intensity of life in Ōtautahi, and in the process she produced some of the most exceptional landscape watercolours to have been painted in this country. The five known watercolours completed from her stay are exquisitely observed and executed. Wainui, Akaroa makes me feel as though I am looking at the landscape through a telescope— from grasses, fences, buildings and pine trees through to the bush on the hill at the end of the beach, everything is so crisp and sharply defined. No broad, loosely applied washes of colour here, just an eye-wateringly beautiful ability to blend watercolour washes in an incredibly subtle manner, the shades of the hills and the sea in the bay. Angus captures something of the spirit of this bay, the change of pace visitors can still experience today.

Rita’s connection with Wainui during her timeout in the summer of early 1943 is highlighted in letters she wrote to her close friends Douglas Lilburn and Fred Jones:

Wainui is charming, the bach is built on a rise overlooking the harbour and opposite Akaroa, and the weather has been rather wonderful.5 … I find the bach very comfortable, most of my subjects are near here, I’m indolent, and I fear, putting on weight. Thinking of Leonardo [da Vinci], I’m aware of much I’ve not noticed before, and how very short is one’s life. Again a hermit … I thought I could be a more simple hermit than I am.6

Peter Vangioni

Curator

Ngāti Porou – tribal group of East Coast area north of Tairāwhiti Gisborne to Tihirau

Kahawai – schooling coastal fish

Mātauraka Maori – Māori knowledge

Whakapapa – genealogy, lineage

Atua – ancestor with continuing influence, god, deity

Tūpuna – ancestors

Tākata – people

Pūrākau – myth, ancient legend, story

Mōteatea – lament

Whānau – extended family, family group

Whakataukī – proverb

Tūpuna māori – Māori ancestors

Whenua – land, placenta

Uku – clay

Mauka – mountain

Awa – river

Manu – bird

Te ao Māori – the Māori world

Whanauka – relative, kin