Morehu Flutey-Henare and Reihana Parata’s Ngā Whāriki Manaaki ‘woven mat of welcome’, Maumahara, sits in front of the Bridge of Remembrance. Photo: John Collie

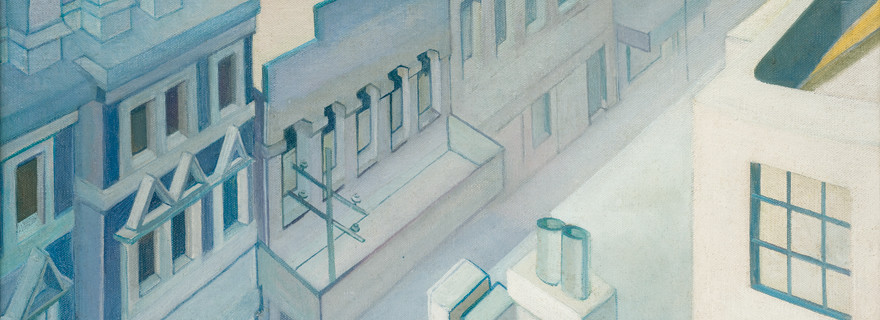

Bringing the Soul

The expression of Ngāi Tūāhuriri / Ngāi Tahu cultural identity in the Christchurch rebuild

As an eleven-year-old boy from Whāngarei, sent to live in Yaldhurst with my aunt in the late seventies, Christchurch was a culture shock. Arriving in New Zealand’s quintessential ‘English city’, I remember well the wide landscapes and manicured colonial built environment. It was very pretty but also very monocultural, with no physical evidence of current or former Māori occupation or cultural presence, or at least none that I could appreciate at that time.

I confess to arriving back earlier this year to check in on the Christchurch rebuild to find the culture shock not quite so stark. In fact, while the presence of Māori and Pacific people remains much less obvious (with the exception of the hi-vis fraternity), there are many parallels between the urban design work I am involved in with mana whenua in Auckland and the work that Ngāi Tūāhuriri / Ngāi Tahu are currently engaged in as they seek to progressively reinscribe their cultural identities into the urban fabric of the city.

While the Canterbury earthquakes have literally peeled away huge chunks of the inner-city colonial architectural overlay and been the catalyst for iwi and hapū influenced urban renewal, the ‘seismic shift’ for Auckland happened at about the same time in 2010 with the creation of the Super City and seven (now six) CCOs, or council controlled organisations.

While for mana whenua in both cities the goal is to see their cultural identities reflected positively in the built and natural environments, a key difference is the nineteen acknowledged iwi organisations in Tāmaki as opposed to the single iwi (Ngāi Tahu) and hapū (Ngāi Tūāhuriri) mana whenua landscape in Ōtautahi. Added to the simplicity and, I would argue, success of this Treaty-based working arrangement has been the creation of Matapopore as the mana whenua organisation ‘responsible for ensuring Ngāi Tūāhuriri /Ngāi Tahu values, aspirations and narratives arerealised within the recovery of Christchurch’.1

Matapopore is led by Aroha Reriti-Crofts, taua of the Tūāhiwi Marae; her role has reportedly not been an easy one, with competing interests both inside the tribe and within the Pākehā community.

However, a meeting with Matapopore Charitable Trust general manager Debbie Tikao reveals, despite some early difficulties, a growing optimism and satisfaction with both the core relationships being forged in the recovery process and the physical results on the ground. This process has seen a range of Ngāi Tūāhuriri / Ngāi Tahu natural heritage, mahinga kai, te reo Māori, whakapapa, urban design, art, architecture, landscape architecture, weaving and traditional arts exponents engaged individually and in teams to work alongside central and local government to meet the hapū and iwi cultural objectives of the recovery plan.

A particularly significant resource for Matapopore and the hapū are the set of tribal ‘grand narratives’ for the rohe developed by Te Maire Tau, which are utilised as the overarching structure to inform particular place-based cultural design responses.

Native wildlife and mahinga kai species are referenced in artworks at the Tākaro ā Poi Margaret Mahy Family Playground. Photo: John Collie

From Tau’s perspective the narratives were a reference point to the tribe’s traditions and whakapapa. How those narratives would be reflected was the challenge; he was not comfortable they could be without the assistance of the tribe’s principal architect,Huia Reriti, who has at least two whare-nui under his belt.

Tikao freely states that with some key projects Matapopore were late to the table and perhaps weren’t able to maximise hapū / iwi urban design, architectural and artistic inputs. However, she says that processes have become progressively streamlined and that good, trust-based relationships with the Council and development communities have now been created with ‘less fear and less scepticism.’ An external affirmation of this reality came recently with a key player publicly proclaiming that Matapopore had ‘brought the soul to the project’.

A walking tour of the inner city confirmed much of Tikao’s current optimism, as I visited some key recent developments and tried to discern the various ways that iwi / hapū cultural imperatives were being expressed along the way.

Tākaro ā Poi – The Margaret Mahy Family Playground – was certainly a highlight, with its proximity to the Ōtākaro / Avon giving renewed meaning to the name of the river – a reference to the place where the children played while the adults gathered kai. Opened in December 2015 as the largest playground in the Southern Hemisphere, its sheer size allows for and actually delivers a large number of opportunities for Ngāi Tūāhuriri to express their cultural presence, particularly in the range of native wildlife / mahinga kai species referenced in the hard landscaping. Here it has been particularly significant for mana whenua to have their tamariki be able to trace their own cultural narratives, and have them reinforced, within a visually stimulating and physically challenging park environment.

Tākaro ā Poi also includes one of the Ngā Whāriki Manaaki ‘woven mats of welcome’. This is a particularly successful project delivered by Matapopore that focuses on thirteen mosaic whāriki, which are being progressively installed within Te Papa Ōtākaro (the Avon River precinct). These whāriki are complemented by large-scale ecological interventions throughout Te Papa Ōtākaro where the hapū (via Matapopore) have been able to provide design leadership roles, including the selection of appropriate native tree and plant species.

Te Kapehu, designed by Arapata Reuben and Hori Mataki, outside the entrance to the Hine-Pāka Bus Interchange. Photo: John Collie

The involvement of local master weavers Morehu Flutey-Henare and Reihana Parata as designers of the whāriki has been central to the project and has allowed the women the opportunity to apply their traditional skills to a new and very public set of canvases. In so doing they are continuing the wider process of taking Māori art and design out of the marae (where whāriki or traditional harakeke mats almost exclusively reside) and providing a new and culturally appropriate artistic typology for the city. The scale of these ground-plane artworks (up to five metres square), prominent locations, cultural significance and artistic sensitivity all help to ensure a significant cultural contribution to Te Papa Ōtākaro, enhancing its role as the flowing life force of the city.

While the Hine-Pāka Bus Interchange was a project where Matapopore involvement came late, I was generally impressed with the architecture and the integration of hapū historical narratives through artistic inputs, in particular to the ground plane, ceilings and columns. Te Kāpehu, the ten-metre diameter compass etched into the bluestone pavers is particularly prominent at the main entrance and records local and distant culturally significant tohu, or landmarks, which are interwoven into a stylised Western compass. The inclusion of significant star constellations such as Māhutonga (Southern Cross) and Atutahi (Canopus) in the ceiling treatments is also quite successful, building as it does, on the renewed interest in Māori and Pacific star navigation in recent years and referencing the Interchange as a contemporary voyaging facility.

Lonnie Hutchinson’s Kahu Matarau forms the façade to the Christchurch Justice and Emergency Services Precinct. Photo: John Collie

While not set to be fully revealed until the middle of this year, Lonnie Hutchinson’s korowai kākāpō façade to the Justice and Emegency Precinct carpark already provides a particularly striking addition to the cultural fabric of the city. The korowai is made up of 1,400 anodised aluminium panels suspended on the thirty-five-metre long Tuam Street façade and has provided an important opportunity for the established Ngāi Tahu artist to contribute her skills to the rebuild. Already much admired, the artwork has provided perhaps the first opportunity (hopefully of many) for iwi and hapū cultural expression to be boldly represented in the vertical plane of the city.

Perhaps the highest profile and oldest post-quake cultural statement remains Chris Heaphy’s planted cathedral waharoa, which appears to exist as a beacon of hope for the Cathedral rebuild as well as acting as an affirmation of Māori, iwi and hapū cultural identity in the heart of the old city.

So, while looking at the rebuild as a whole, the expression of iwi and hapū cultural identity across the city to date appears sporadic (somewhat like the rebuild) and sometimes relatively subtle, some very successful signature projects have been completed. And there are several more significant projects in the pipeline which will have benefited from ground-level Matapopore design collaboration.

Ngāi Tahu and Ngāi Tūāhuriri have justifiably expected that the Christchurch rebuild would allow for their cultural identity to be strongly represented again within a post-colonial Ōtautahi. On the present trajectory, their aspirations appear well founded.

Kia hoe kotahi!