Hely Smith The Fog Horn 1896. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the Canterbury Society of Arts 1932

Reading the Swell

The art of the sea has always been the art of vastness—without edges and with potential for infinite extension. It is this immensity that has invaded the Reading the Swell exhibition; finding its way through the automatic doors when no one is looking and quietly expanding the walls. Like sailors, artists have laid soundings in this uncharted vastness. Reading the Swell is a small and pointed selection of those soundings that see fit to make sense of the sea.

The vastness they depict means these works do not sit passively in a gallery setting. Impossible to pin down, they defy containment and loom from the walls. To gallery patrons, this ‘looming’ can be disconcerting, playing tricks with their perception as haven and murderous wilderness mix together and shift before their eyes. The sea gazer, like the gallery patron, is also confronted by the sleight of hand that a looming ocean presents, and it is perhaps this phenomenon that unifies the experience of the audience.

Looming is an optical phenomenon peculiar to the sea; one of those obscure maritime topics that has been largely ignored, except by a few acutely observant sea gazers. In 1855 John Brocklesby published his Elements of Meteorology; with questions for examination, designed for schools and academies, which, for the first time, discussed the effect. Brocklesby published on a wide range of natural science but it was only late in his life that he found the fascination of the sea and all its optical tricks. Until then, looming was cast aside as the work of the devil but Brocklesby dispelled all that with a dose of hard physics.

His initial summation seems harmless enough: ‘Looming is caused by local changes in the temperature of the atmosphere causing irregularities in refraction and distortions in perspective,’ but it is his explanations that strike the unwary sea watcher with the power of a vivid hallucination. Like a neat margin ruled on a page, the horizon fools the observer into the idea of a limit to the sea but then uses this false margin to play tricks with our eyes. Ships and islands appear to hover in the air and distant shores are brought closer.

Julius Olsson Moonlight c.1910. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the Canterbury Society of Arts with assistance from the John Peacock Bequest 1912. Presented to the Gallery 1932

Brocklesby shoots himself in the scientific foot by attempting to illustrate the concept of a sailing ship being ‘hull down’. Only the rigging and superstructure are visible above the curvature of the earth and, as the ship gets more distant, it appears to topple over the horizon, confirming what all landlubbers know deep in their soul; that the earth is flat and that you can sail off the edge.

Perhaps it is the obscure element of looming that draws people to the edge of the sea or indeed the gallery, seeking what Thomas Jefferson called the water prospect without termination. Like art, the view of the sea seems to open something else in the land bound. It infuses the walls of Reading the Swell. Hely Smith’s The Fog Horn (1896) is wreathed in it. The comfort of the horizon is entirely obscured by fog and the ghostly apparition of a sailing ship bears down with nothing short of menace on the pilot ketch waiting at anchor. It is one of those moments that occurs often at sea and that even modern technology has not managed to quell. Fog over the ocean distorts sound as well as vision, and it is this hint of peril that drums away in the background of The Fog Horn. Smith has included the pilot ketch’s anchor line to ground his landlubber audience and to trick them into believing that land lies only a few fathoms below. But in reality, the crew of the ketch would have been hove to in deep water, drifting slowly sideways, their mizzen keeping their bows to the weather as the pilot waited for a potential client. Any hint of land or the proximity of the sea floor would be a holy terror to these sailors, full of the uncertainty that fog inflicts on navigation.

Knowing the terrestrially bound audience’s need for security in the form of land defines Julius Olsson’s Moonlight (c.1910). Olsson was a keen yachtsman as well as artist and was acutely observant of both his element and his audience. Moonlight positions the viewer on a headland, safe from the perils of the sea, but with access to all the delights of a coast seen by moonlight and the reassuring swish of surf on the rocks below. Exactly the sort of swish that would horrify the sailor. The haven of the harbour is faintly visible in the form of the lighthouse. Like Smith’s anchor cable, it is a trick he plays with the audience to make them feel safe, masking the murderous ocean with a patina of moonlight, prospect and dry-footed assurance.

John Gibb Lyttelton Harbour, N.Z. Inside the Breakwater 1886. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna

o Waiwhetū, presented by the Lyttelton Harbour Board, 1989

Petrus van der Velden The Leuvehaven, Rotterdam 1867. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased with assistance from Gabrielle Tasman in memory of Adriaan, and the Olive Stirrat bequest. Purchase supported by Christchurch City Council’s Challenge Grant to Christchurch Art Gallery Trust, 2010

It is the harbour as a haven that both John Gibb and Petrus van der Velden examine in their respective works. This is the sea as their terrestrial audience would prefer it: contained and subdued by the hand of commerce. Gibb’s Lyttelton Harbour (1886) has an air of prosperity about it, depicting a colony on the make. Even today, the workings of

this harbour give a good indication of the health of New Zealand’s economic balance sheet; the coal going out roughly equals the second-hand cars coming in. The image is set facing inward with no hint of the infinite horizon to the east. Gibb’s harbour ignores the open sea and all its potential to trick the viewer. His sea’s only purpose is to provide a medium for import, export and prosperity to a new colony.

Petrus van der Velden’s The Leuvehaven, Rotterdam (1867) has the same air of orderliness. The sea has been subdued into a street to serve the demands of commerce. In his later years, van der Velden moved to New Zealand and developed a passion for the unruliness of the wilderness. Perhaps he had a glimpse of the future, as the bombs of the Luftwaffe levelled most of the scene of the The Leuvehaven, Rotterdam in World War II. This knowledge, something only a contemporary audience could have, looms before the work—a warning shot to the gallery-goer. Like a ship that appears to topple over the horizon, it gives the viewer some unease about the certainty of what constitutes a haven from the sea.

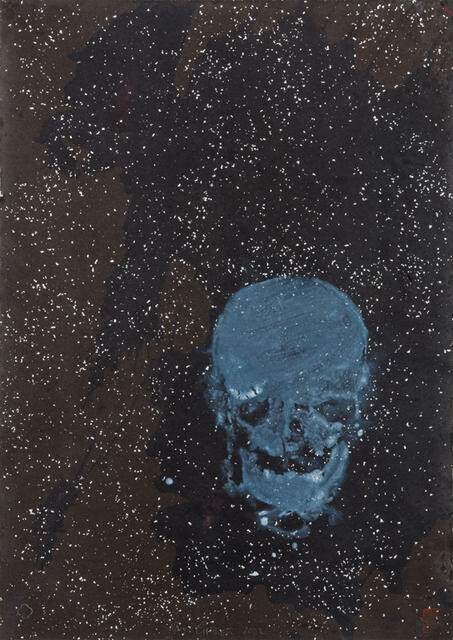

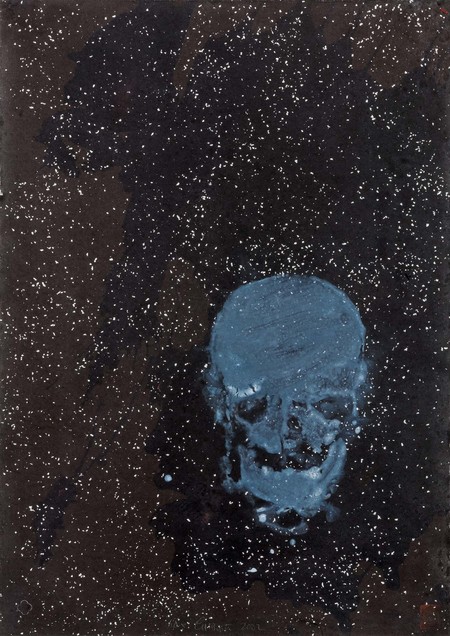

Tony Fomison Captain Ahab Peg Legged Hunter of the White Whale 1981. Oil on canvas board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented to the Gallery by Peter Wells 1984

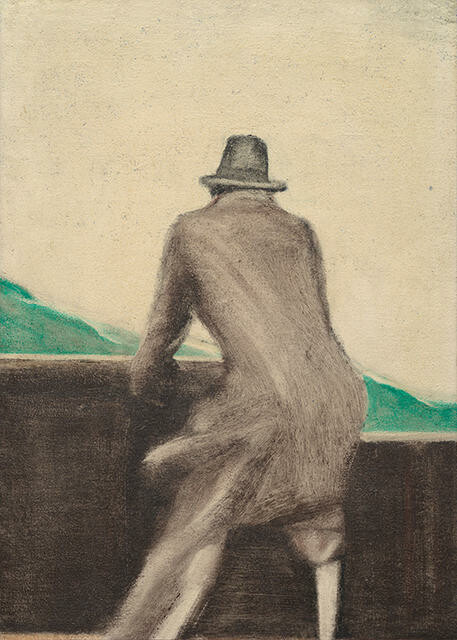

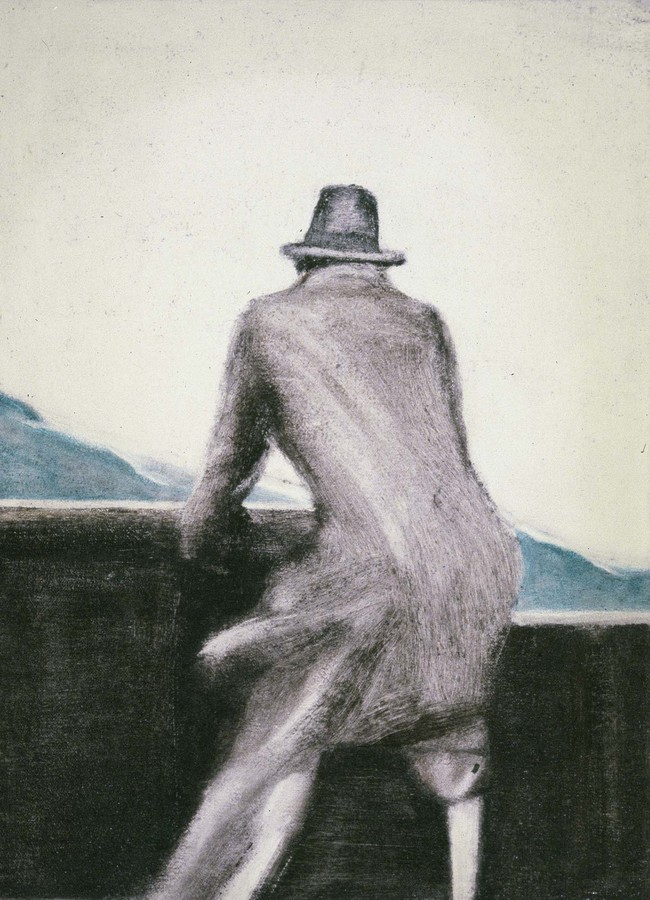

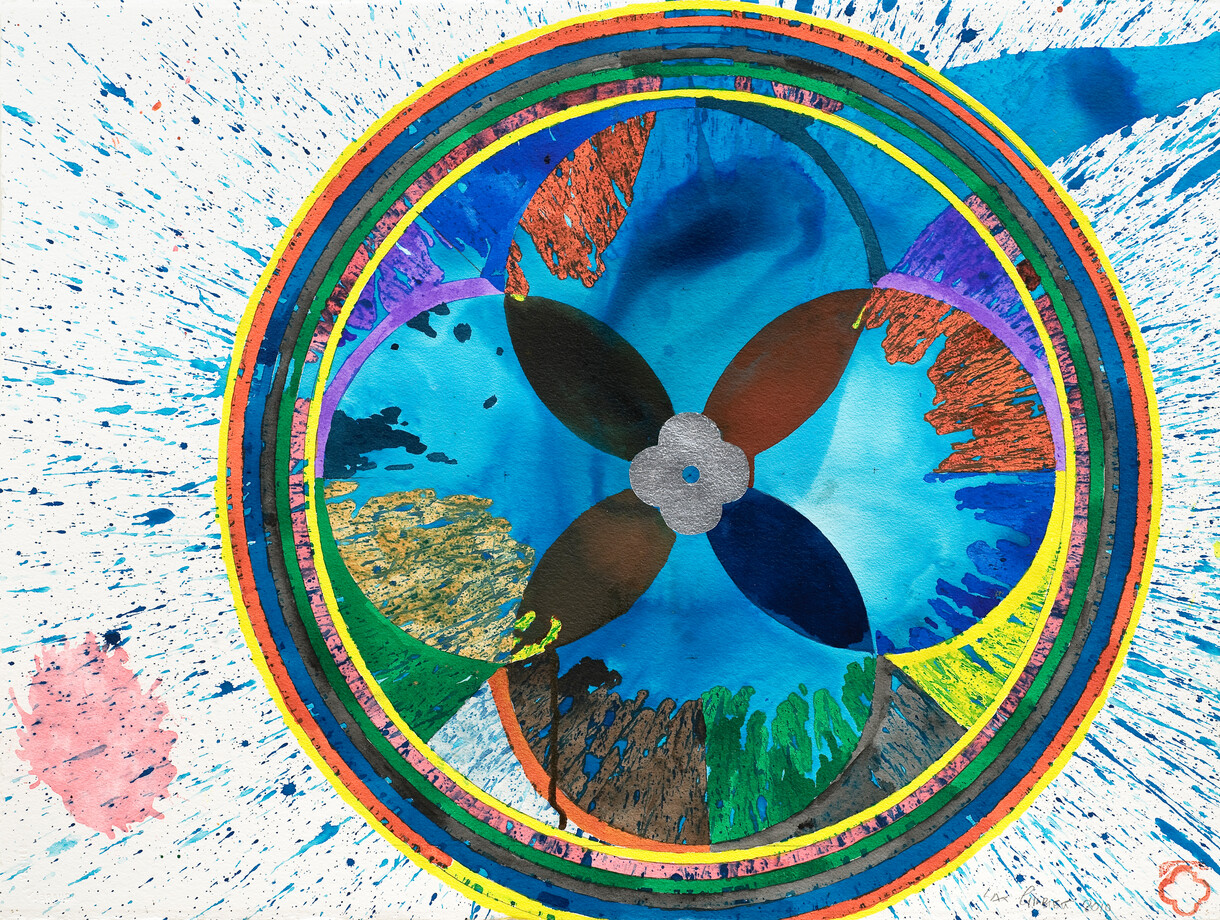

Max Gimblett Lost At Sea—2 2002. Acrylic polymer / Japanese Kinkami Silver Fleck 100% Kozo Handmade Paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, the Max Gimblett and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Gift 2011

This sense of foreboding about what the sea and the human mind are really capable of is captured by Tony Fomison in his rendition of Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab. Ahab is locked in an intense gaze, not at the sea, nor the great white whale that took his leg, but at the land; a land that looks remarkably like Banks Peninsula viewed from the sea. Perhaps Ahab’s obsession with the great white whale is fuelled less by revenge than by a desire to escape from the distraction and futility that are a sailor’s life ashore. The hunt for a murderous whale focuses the senses, whereas the prospect of land only induces the hunch-shouldered anger of a man about to spit in disgust at the vision before him.

Max Gimblett’s Lost at Sea—2 (2002) moves our focus to the sky, yet does not escape the effects of looming. Sailors look to the sky to see the future, to find their position on a seemingly featureless watery world and to glean a hint of the weather to come. The stars whirl above the ocean with the certainty of a giant cosmic clock and it is a shock to find the ominous features of a skull emerging in their midst like a sinister Magellanic cloud. The skull changes form with the lighting, almost disappearing when the gallery lights go out. The image looms as if Gimblett is hinting at something of our future and of the waves.

![Louis Auguste de Sainson La Corvette l’Astrolabe tombant tout-à-coup sur des récifs dans la baie de l’Abondance, (Nouvelle Zélande) [The Corvette Astrolabe falling suddenly on reefs in the Bay of Plenty, (New Zealand)] 1833. Hand-coloured lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2014](/media/cache/b4/ed/b4ed8151602269786bd11d01c245145b.jpg)

Louis Auguste de Sainson La Corvette l’Astrolabe tombant tout-à-coup sur des récifs dans la baie de l’Abondance, (Nouvelle Zélande) [The Corvette Astrolabe falling suddenly on reefs in the Bay of Plenty, (New Zealand)] 1833. Hand-coloured lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2014

William Wyllie The Sloping Deck 1871. Oil on card. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented

by the family of James Jamieson 1932

The uncanny similarity of fate emanates from Louis Auguste de Sainson’s La Corvette l’Astrolabe (1833). The depiction is of Dumont d’Urville’s ship the Astrolabe striking the reef that would later come to bear its name. The seas are vertically surreal, hovering, forever

on the edge of breaking, drawn for direct impact on his land-dwelling audience. The scene is viewed from above, as if from the back of a seagull, where the audience is rendered an observer, not a participant in the ungodly tableau. The ship sits immobile while all around is calamity on the move. There is something unnerving in de Sainson’s depiction of the sea, something that hints at its ability to destroy even the finest of havens; something that hints at the future and a ship named Rena going aground on the very same reef with horrendous consequences.

If de Sainson’s work hints at the almighty power of the sea, then William Wyllie’s The Sloping Deck (1871) confirms it; a scene of utter desolation, full of Conradian shimmering terror as the haven visible in the background turns hellhole. For the survivors clinging to the stump of the mizzenmast, drowning or being dashed to death on the rocks is all that lies in prospect. In the awful scene he depicts in The Sloping Deck, Wyllie unites the landlubber and the sailor. The landlubber’s distrust of the sea is confirmed and what all sailors have secretly known is revealed.

The mask of humility has been torn off and the diabolical violence that lurks beneath its waters has been unleashed. The looming has gone from an amusing trick of the light to an inescapable horror from which we cannot avert our gaze.

![La Corvette l'Astrolabe tombant tout-à-coup sur des récifs dans la baie de l'Abondance, (Nouvelle Zélande) [The Corvette Astrolabe falling suddenly on reefs in the Bay of Plenty, (New Zealand)]](/media/cache/f3/ee/f3ee101dfaa85206f23e6a6871764577.jpg)