Turn Around and I’m Gone Again

Ah Xian China, China—Bust 28 1999. Porcelain body-cast, hand painted in overglaze enamels. Powerhouse Museum, purchased 2000. Photo: Richard Weinstein

The public lives of artworks can be occasional and itinerant—they emerge from the cosy sameness of storage into fresh locations and contexts. Many make their first public appearances alongside siblings from their maker’s studio, but later find themselves in very different company. While some resolutely maintain their identity no matter how or where they are shown, others open up to additional associations and meanings. Fittingly for a show about the power of alternative identities, several of the works in Dummies & Doppelgängers have evolved over time, shapeshifting into new lives or likenesses.

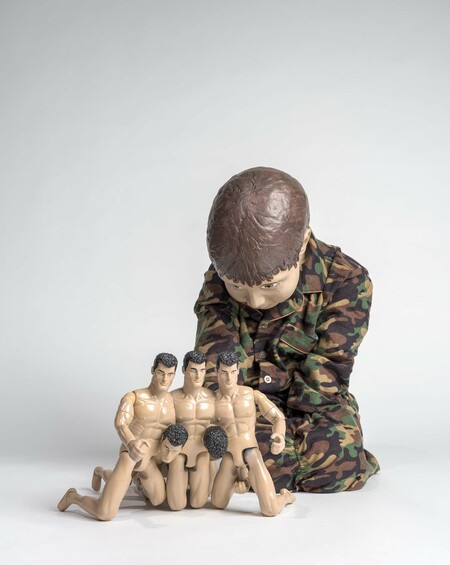

Scott Eady Boy 2006. Fibreglass, acrylic, fabric. Courtesy of the artist and the Art House Trust, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Scott Eady’s Boy—an unexpectedly menacing work that reflects the artist’s ambivalence about the messages our society sends our children—required only a fresh pair of pyjamas from the artist to ready him for his current outing. Other transitions have been more circuitous. Francis Upritchard’s Eeling in the Ōtākaro is a sinuous, writhing tangle, steadied by the deep concentration projected by the two human figures in its midst. I say ‘human’, but with their strangely elongated limbs they’re weirder and more wonderful than your typical Homo sapiens. Upritchard was inspired by two yōkai, or fabulous beings, from Japanese folklore known together as Ashinaga-Tenaga (Long Legs and Long Arms). Ashinaga-jin (足長人) has extremely long legs, while Tenaga-jin (手長人) has extremely long arms. With Tenaga-jin sitting on Ashinaga-jin’s shoulders, they can fish in deeper and more abundant waters than others can reach alone, symbolising the value of cooperative relationships. In Upritchard’s reimagining, they wade in the winding Ōtākaro awa of Ōtautahi Christchurch, and the fish that surround them are its velvety native longfin eels, tuna. Upritchard wanted to emphasise how the city’s difficult recent history of devastating earthquakes and horrifying terrorist attacks has made it more important than ever for people here to try to work together. She made her eelers during the Gallery’s artist residency at Sutton House, a stay that coincided with the Covid pandemic, and they attained an added resonance at a time when cooperation for the good of all was so demonstrably essential to survival.

Francis Upritchard Eeling in the Ōtākaro 2021–3, Bronze (from balata rubber), limestone. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2023 with the support of the Ngarita Charlotte Hounam Johnstone bequest

Ah Xian China, China—Bust 39 1999. Porcelain body-cast with yingqing glaze. Powerhouse Museum, donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Gene and Brian Sherman, 2008. Photo: Richard Weinstein

Eeling in the Ōtākaro was first exhibited in Upritchard’s 2022 exhibition, Paper, Creature, Stone. The figures and eels were composed of balata—a wild rubber sustainably extracted from trees in the Amazon in Brazil. This unstable material requires patience, careful handling and an artist willing to embrace unpredictability. The resulting sculptures have a texture that is hard to describe; somewhere between pulled taffy and petrified wood. They’re stringy and springy, smell like cold, damp earth and are prone to becoming brittle as they dry out. In the months between the packages of balata arriving at the Gallery from Brazil, and Upritchard starting work, they had to be regularly taken from a handling room up to the conservation lab for soaking, leaving a slight whiff of mouldy potato in the air behind them. This process was repeated with the completed sculptures before the exhibition. It wasn’t a long-term solution, however, so in order to bring the work into the Gallery’s collection and ensure its longevity, it was cast in bronze. For this, it was sent by sea to Vincenza, Italy, and the specialist Guastini art foundry with whom Upritchard has established a working relationship. The casting process sacrificed the original balata but retained the nuances of texture and movement that make the work so unforgettable. After being inspected and approved by the artist, Eeling in the Ōtākaro was transported back to Ōtautahi and resecured to its boulder to await its new-state debut in Dummies & Doppelgängers.1

Ah Xian’s exquisitely surfaced porcelain busts have also travelled between hemispheres, but in their case this distance was central to their conceptualisation. They are part of China, China, an extraordinary series of more than eighty individual works the artist began in 1998. They reflect his search for a means of expression that would honour the artistic traditions of his Chinese birthplace while also acknowledging the new context of his adopted Australian home. The China, China works shift fluidly between times and places, and between surface and spirit. After seeking political asylum in Australia in 1990, Ah Xian returned to China in 1997 to make this work. He travelled to Jingdezhen, a small town whose skilled artisans have been renowned over centuries for their intricately decorated porcelain, a material so synonymous with the country in which it is made that it is known simply to many Westerners as ‘china’. Ah Xian described his desire to work with the artisans of Jingdezhen, and to commission them to incorporate traditional designs and motifs in the decoration of his body casts, as a way of resurrecting historic artmaking traditions while also working within the new tradition of conceptual art. Unlike the Western archetype of the lone genius, the artisanal work in Jingdezhen is performed by many unnamed hands and Ah Xian’s works acknowledge the value of such collective practice. At the same time they emphasise the uniqueness of each individual life: every bust was cast from a different person, including the artist’s wife Mali Hong (bust 28), his family and friends. Patterns created through varied techniques such as hand painting, cloisonné and specialist glazes suggest how a person’s cultural background and life experience leave indelible traces, here made visible on the ‘skin’ of each sculpture.

Alex Seton Standing Manikin Target 2020 Bianca Carrara marble. Collection of the artist, Sydney

The catalyst for Alex Seton’s haunting Standing Manikin Target came as a surprise to the artist. After spending most of 2007 travelling, he returned to Sydney to encounter the central city as he had never seen it, effectively locked down by security measures for the APEC Leaders’ Week conference. A week prior, he had been searched and detained for several hours by police in a London underground station, on high alert following a terrorist attack on Glasgow Airport. Still jarred by that experience, he was horrified to find his hometown also bristling with armed police and rooftop snipers, and a 5km concrete and wire security cordon around the politicians. It was an unprecedented level of intervention that, unbeknownst to the artist, had prompted intense public concern and media debate in the weeks leading up to the conference. Compelled to document the fraught grimness of this unfamiliar environment, Seton walked through and photographed the blocked-off streets, somehow avoiding the attention of police who were confiscating cameras and attempting to shepherd people away from the scene. After standing in front of a vehicle convoy to photograph it and being joined by a swell of protestors, he was forcibly removed. It was later revealed that more than 200 of the uniformed officers present had removed their badges to prevent themselves from being identified for complaints of assault.

Disturbed by what he saw as overreach by the authorities and an excessive show of force that escalated tensions rather than reducing them, Seton returned to his studio. The sculpture he subsequently produced in response was rendered in smooth white Carrara marble—its elegant appearance offering apparent contrast to the visceral physicality of his experience. Yet the simmering violence and sinister atmosphere of that day can be felt in Seton’s meticulously finished work. It is based on a ballistics-gel target dummy that was developed for sniper training by the Australian Special Forces. Carefully designed to represent the size and shape of an ‘average’ human, the original practice dummy contained target sensors and robotics that allowed it to measure, and therefore hone, the accuracy of shooters. Its wide base allowed it to be fixed to a vehicle for moving target practice, while the exaggerated swell of its elongated throat represented the optimal ‘kill zone’ of heart and lungs. In this context, Seton’s customary use of marble attained an additional association, recalling the sombre stonework of a war memorial or mausoleum. When shown outside as part of a recent exhibition at Contemporary Sculpture Fulmer, near London, the pure white stone of the manikin was set against green spring grass, bearing a chilling resemblance to headstones in a military cemetery.

Amanda Newall Blue Ted 2022. Faux fur, stuffing, velveteen, plastic eyes and nose, plastic tube. Collection of the artist

Our favourite toys are supposed to be comforting and constant, remaining safely anchored in memory when we reach adulthood. Amanda Newall’s childhood companion Blue Ted, however, is anything but predictable. He made his first appearance shortly after she did, arriving as a gift from her grandmother to welcome the new baby. Outlandishly oversized and clad in electric blue faux fur, the bear was a powerful presence in her growing-up years, oscillating effortlessly between the real, the imagined and the somewhere-in-between. Years later, as an adult, Newall was shocked to discover his remains disintegrating in a plastic bag on her parents’ property. After such an abrupt and confronting demise, it’s perhaps not surprising that she would eventually decide to resurrect him. While undertaking a residency at Joya: AiR in Andalusia, Spain, in 2021, Newall sewed an accurately scaled and wearable replica from memory, and slipped into the skin of her childhood familiar. In a video taken for her by another artist, she prowls weirdly through the countryside in the baking heat, breathing with difficulty through an internal snorkel and gingerly picking her way over prickly grass and stones in her bare feet. It makes for strange and unsettling viewing—a bedroom bear released into the wild. Blue Ted’s black button eyes allow the wearer no view of the outside world and, on his furry belly, six extra noses are lined up like nipples. Newall’s adult legs and arms protrude beyond the furry blue suit, creating a human/bear hybrid that is simultaneously creepy and vulnerable. And yet, if Newall’s reinhabiting of her childhood was uncanny, the world around her was even stranger. The residency took place during the Covid pandemic, against a backdrop of lockdowns, mass masking, social distancing and global anxiety. Wrapping yourself in the cloak of childhood speaks to an impulse many of us felt then—the yearning for protection and comfort, the attempt to cocoon ourselves by returning to what seemed like simpler times. The awkwardness of the fit acknowledges both the futility of such magical thinking and the impossibility of returning to our childhood selves: our time out in the world reshapes us, and we can’t go home again.