Our Instinct Enhanced

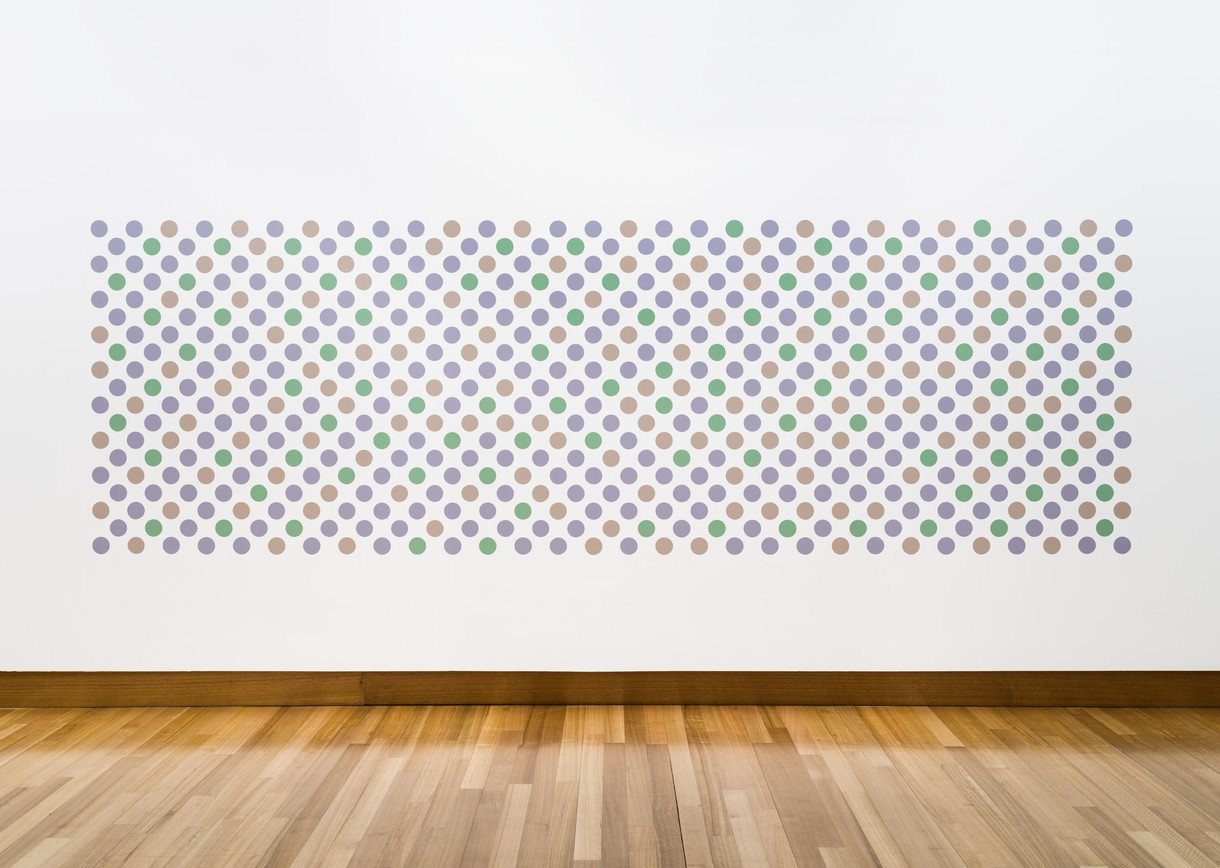

Bridget Riley Cosmos (detail) 2016–17. Graphite and acrylic on plaster. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, acquired through the Christchurch Art Gallery

Foundation with the generous help of Heather Boock; Ros Burdon; Kate Burtt; Dame Jenny Gibbs; Ann de Lambert and daughters, Sarah, Elizabeth, Diana, and Rachel;

Barbara, Lady Stewart; Gabrielle Tasman; Jenny Todd; Nicky Wagner; and the Wellington Women’s Group (est. 1984). © Bridget Riley 2017. All rights reserved

What does Bridget Riley’s art mean? We might imagine that a wall painting titled Cosmos (2016–17) referred to life within a cosmos, an order than encompasses us, whether natural or divine. The designation connotes a degree of philosophical speculation, unlike the direct descriptions that Riley occasionally employs as titles, such as Composition with Circles. But whatever meaning we derive from viewing Cosmos will be no more intrinsic to it than its name. Attribution of meaning comes after the fact and requires our participation in a social discourse. Every object or event to which a culture attends acquires meaning; and Riley’s art will have the meanings we give it, which may change as our projection of history changes. Meaning, in this social and cultural sense, is hardly her concern.

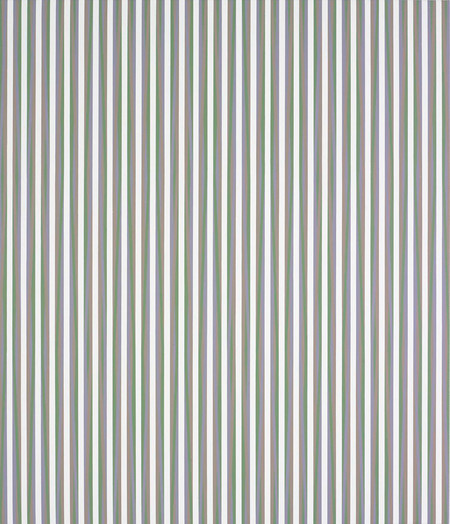

Bridget Riley Vapour 2 2009. Acrylic on linen. Private collection. © Bridget Riley 2017. All rights reserved

At an early stage of her career, Riley wilfully stepped outside history: ‘While one has to accept that the role of art and its subjects do change, the practical problems do not. ... True modern painting, I believe, should always be a beginning – its own re-invention, if you like.’1 She has been exceptionally strict about avoiding aesthetic trends. During the 1960s, works such as Black to White Discs (1962) may have initiated a fashion for bold optical effects; but this historical consequence was inadvertent, and Riley shunned its significance. Part of, and yet apart from, her era, she aims to function as an artist, not an agent of history. To understand her attitude, we need to accept that art and history run separate courses, though the notion will seem paradoxical, especially to those convinced that a social practice (art) cannot remain independent of historical forces (economics, politics, ideological contestation).

Riley grants that the ‘role of art’ changes. Yet this social and historical role is merely an aspect of the art that an artist creates. Riley is at the extreme end of the scale that differentiates those who self-consciously intervene in history (play a role) from those who would supersede history by the force of human feeling. Her aesthetic target is perception, which opens individuals to feeling beyond the limits of their identity as the subject of a culture and a history: ‘Perception constitutes our awareness of what it is to be human, indeed what it is to be alive.’2 What Riley says about art and life is more than metaphorical; people do experience art as sensory and emotional liberation. Academics debate competing theories of the human subject – its theological, anthropological and ideological origins, and even its end in a post-human condition of fluid identities.3 These cultural constructs exist only within a historical, conceptual frame. To the contrary, Riley’s ‘human’ is an organic life form endowed with bodily senses and psychosomatic feeling. The human is us. And it includes all others.

Riley’s art engages what escapes the notice of history. I know of no other examples of abstract art that quite match hers in independence from a lineage of developing aesthetic practice, its cultural allegiances, and its strategic swerves. Yes, Riley now belongs to our official histories of art, but historical discourse cannot explain or retroactively position her actions and their results. Critics are reduced – or perhaps elevated – to describing her art in simple admiration. If Cosmos is a cosmos and therefore an order, Riley’s art calls on us not to discuss the place of order in contemporary culture, but the nature of the order we are actively observing – how it feels. In viewing her compositions, a regular array of stripes, waves, circles or ellipses may verge on non-order, because her distribution of elements results from her intuitive grasp of emergent phenomena of interest. She takes sensation where it leads her: from study to study and, finally, to a completed work in which she commits her trust in that initial sensation.

Many late twentieth-century artists have made stripe paintings, but none reaches the degree of chromatic intensity and visual surprise that characterises Late Morning I (1967), Serenissima (1982), or Aria (2012), all of which generate phantom colours that we perceive along with the colours materially placed on the canvas. Riley’s art induces phenomena as her paint collaborates with light and the physics of nature. The reds, greens, and blues of Late Morning I give rise to an aura of yellow that appears, disappears and appears again as the field of the painting vibrates with internal energy. Other works, somewhat more complicated, also involve colours we see yet cannot locate. Along with its predecessor Vapour (1970), Vapour 2 (2009) twists three chromatic greys round each other to form vertical bands, each an amalgam of off-green, off-violet and off-orange.4 Riley notes that much of the perceived colour ‘is not actually painted. It emerges solely through visual fusion.’5

The interactions of colour do not render Riley’s stripes of greater cultural value than those of other artists, but hers differ qualitatively. She often reduces a formal composition to utter simplicity – parallel bands, a grid of discs, a systematic rotation of ellipses (Nineteen Greys, 1968). The regularity leaves her movement of colour and value free to attain unforeseen complexities of nuance. So questions addressed to Late Morning I or Cosmos or any other Riley painting should not return to the cultural meaning of the genre: stripe painting, circle painting, abstract art, late modernism or whichever category might seem to apply. Nor should we direct interpretation to the literary allusions or concepts a title might suggest. Riley’s metaphors – ‘aria’, ‘vapour’, ‘cosmos’ – often relate to music or atmospheric conditions, along with movement, space and light. The metaphoric designations are evocative, but they only approximate what is to be perceived in viewing the paintings. A title should never short-circuit sensation. Simply put, Riley’s issue is human experience. And the central interpretive question becomes: What does her art do?

Installation view of Bridget Riley: Cosmos, 3 June – 12 November 2017. Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. © Bridget Riley 2017. All rights reserved

Bridget Riley Copy after The Bridge at Courbevoie by George Seurat 1959. Oil on canvas. Private collection. © Bridget Riley 2017. All rights reserved

Courbevoie to Cosmos

At a relatively early stage in her self-directed aesthetic education, Riley posed the question of ‘doing’ to the art of Georges Seurat (1859–1891). She had no interest in placing herself in a historical lineage or taking up unanswered questions left by this early modernist master. She merely sought a suitable candidate to provide her with advanced instruction. In 1959, with the encouragement of her friend Maurice de Sausmarez (1915–1969), Riley set about to copy Seurat’s Bridge at Courbevoie (1886–7). Her experience was indirect, but intense nevertheless. Although Seurat’s painting was available for viewing in London, she chose to study a reproduction from a book as her working model.6 She refers to her result as a ‘transcription’ of Seurat, ‘intuitive with the clues provided by him’.7 If we resort to a precise technical vocabulary, her transcription was not a ‘copy’ but an ‘imitation’. The purpose of copying is to make as precise a replica as possible, whereas imitation pertains to an action or process, not its product. For the purposes of imitation, a reproduction works as well as an original as the source. Alone in her studio, concentrating on the information contained in a low-resolution printed illustration, Riley acted out Seurat’s method, his use of discrete strokes or points of relatively saturated hues. Her aim was to comprehend his mental attitude, to think and see as he did. ‘I followed his mind – not his method’, she says.8 From mark to mark, colour to colour, she was interpolating the perceptual process of another, looking to what was happening between the marks where the colours interacted: ‘Imitating a work is simply one of the best ways of internalising its artistic logic.’9 Her sensitivity to the aura of yellow that arises in Late Morning I may have had its initial awakening in her probing of Seurat’s sensory mind.

The original Bridge at Courbevoie has modest dimensions of 46 x 55 centimetres; its diminutive reproduction, Riley’s source, measures 18 x 22 centimetres. As the support for her copy, she chose a canvas beyond both, measuring 76 x 96 centimetres (very close to the proportions of the reproduction, slightly elongated in relation to Seurat’s painting). Because she was using a format of greater scale, we might expect Riley to have enlarged proportionately the divisionist marks of her model. Instead, her marks are fewer and disproportionately scaled up (though still decidedly divisionist in character). She effectively magnified the traces of Seurat’s visual thinking, the better to inspect them as elements independent of his subject matter. To establish a foundation, she began with a palette of her own choosing, based on the primaries, but heightened in tonal value: pale blues, which she applied first, followed by pale pinks, followed by pale yellows.10 Concentrating on expanding the range of colour, she added several brilliant points of red in the left foreground area of green grass, even though such colours were not visible in the printed source. Riley knew that spots of red existed elsewhere in Seurat’s actual painting, so they were a fair topic of enquiry. The crudeness of the book illustration may have afforded an advantage – leeway for the play of her aesthetic imagination and explorative intuition. Her reds dance rhythmically across the surface, as Seurat’s do in places, but this effect is more pronounced in Riley’s version, especially in the area of the distant shoreline and foliage. She was anticipating her abstract-art self, counteracting Seurat even as she gathered information from him, extracting bits of colour-play from his painting, reworking them as intensified optical experience. She recognised that every red, every green, every other hue lives its transitory life within human perception. With regard to ‘pictorial elements’ of all kinds, from Seurat’s points to her own expansive discs, she later said: ‘I have to find out what they can and cannot do.’11 Not long after making the Courbevoie copy, she painted a divisionist invention that she titled Pink Landscape (1960). The experience led her to realise that her method ought to generate ‘the thing seen’ rather than ‘the thing painted’ – the inverse of Seurat’s procedure.12 By manipulating a set of pictorial elements in a certain way (the method), a configuration worth painting would be discovered.

Perhaps my analysis of Riley’s early work takes this turn from representational naturalism to inventive human perception because I am aware of her appreciation of Seurat as she expressed it after years of investigating abstract forms. The wonder of Seurat’s art, she has said, is its capacity to reveal what ‘we cannot quite see’. Her succinct statement implies that we perceive only tenuously what an artist fully committed to perception puts directly before our attention and feeling – ‘an experience just beyond our visual grasp ... the im-perceptible.’13 As if to extend Seurat’s project, she examines situations in which customary exercises of sensation fail. She deals with features of experience that leave no cultural record, enter no history, and assume no ‘meaning’. For an artist, Riley says, ‘those fleeting sensations which pass unrecognised by the intellect are just as important as those which become conscious.’14 We must increase our perceptual capacity in order to encounter aspects of existence – of the cosmos – that await our acknowledgement. Riley has defined the elusive talent of painting as opening ‘a small gap of pure perception ... before conceptualisation takes over.’15 Concepts put a lid on perception and contain it. Exceptional artists are not those who create alternative worlds, but those who awaken a dormant potential within: ‘[Seurat] arouses the somnambulist element in perception.’16 At Courbevoie and elsewhere, he took the lid off. By her imitation, Riley did the same.

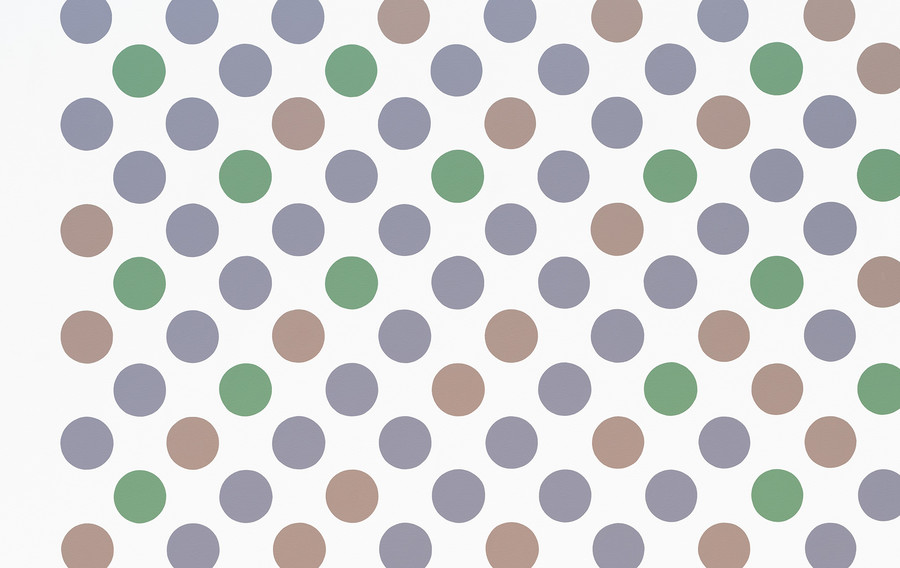

Seurat remains in Riley’s current work: ‘[A] connection ... seems to lie in the touches of colour used in both the Seurat copy and Cosmos. It is the separate, discrete nature of these touches that generates spatial movement and depth.’17 The ‘touches’ are the circular discs. Their geometric order is predictable since it remains true to its diagonal grid. Their greyed colour, however – off-green, off-violet, off-orange – is extremely interactive and therefore unpredictable, all the more so because of the irregular distribution of the three elements. Chromatic greys (also seen in Vapour 2) are inherently unstable, hypersensitive to each other and to the visual environment. Riley sequences the colours intuitively, generating diverse areas of chromatic concentration, contrast, and détente (release, relaxation). ‘I do not start my work with a destination in mind’, she says.18 The horizontal expanse of Cosmos, 460 centimetres wide, necessitates visual scanning in time – cinematically, anamorphically. Even for a single viewer, Cosmos, like a multitude of stars and planets viewed through the atmosphere, will never offer precisely the same appearance. Its horizontality inhibits a simple reading of the diagonals as unbroken parallel ‘lines’ or rows of discs. Nevertheless, analysis reveals a single diagonal sequence that extends monochromatically to sixteen discs of greyed violet and two others of fifteen violets. My senses resist this type of analytical accounting; when I did it, it felt perverse and unnatural. My eye would prefer to jump across the diagonals to left or right or follow this or that diagonal on a whim.19 Such intuitive viewing is the natural response. However the eye is impelled, it will find its proper rhythm. Riley leads us realise that we learn to see... by seeing.

In a recent conversation with curator Paul Moorhouse, Riley noted that the passages of colour generate ‘tensions ... pulls between [the elements] which seem to be almost gravitational. The title of the work alludes to this: a sense of enormous space and depth.’20 The ‘pulls’ within the gravitational field that Riley has created do not result from a calculation of known forces; these are tensions discovered only in the process of working with the circular elements of colour, distributing and arranging them. The relative uniformity of value on the grey scale of Riley’s variants of green, violet and orange intensifies their interaction since no hue dominates the other two (though violet discs seem to outnumber the green and orange). The green hue appears somewhat more chromatic (closer to saturation) than the orange and the violet, because a saturated green has a middle value to begin with, whereas a saturated violet is relatively dark and a saturated orange is relatively light. This is speculation on my part, but I believe that the violet and orange needed to be muted to a greater extent than the green in order to reach a common value in the middle range. Analogous in value, the greyed hues contrast chromatically. These two essential qualities, value and chroma, act divergently within Cosmos, which causes the whole to seem simultaneously sonorous and assonant. To describe the effect alternatively, as both harmonious and discordant, would introduce too much of a polarity, given how nuanced the coloristic effect appears. In their positioning, the greyed colours create the tensions and pulls to which Riley refers. With the ‘gravitational’ field energised, her ‘cosmos’ acquires phantom depth along with its actual breadth – a passive grid comprised of active irregularities, a cosmic order of idiosyncratic elements.

Bridget Riley Cosmos 2016–17. Graphite and acrylic on plaster. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, acquired through the Christchurch Art Gallery

Foundation with the generous help of Heather Boock; Ros Burdon; Kate Burtt; Dame Jenny Gibbs; Ann de Lambert and daughters, Sarah, Elizabeth, Diana, and Rachel;

Barbara, Lady Stewart; Gabrielle Tasman; Jenny Todd; Nicky Wagner; and the Wellington Women’s Group (est. 1984). © Bridget Riley 2017. All rights reserved

Intuition to Instinct

I have already quoted Riley’s remarkable statement: ‘Perception constitutes our awareness of what it is to be human.’21 At its core, art, which addresses perception, is human. We have an instinct for what we call beauty, which we might just as well call ‘that which is’ or ‘all that exists,’ because humans are capable of perceiving beauty in the entirety of natural creation and the entirety of human creation. This is so as long as the cultural politics of history do not interfere. I can imagine that our prehistoric ancestors perceived beauty in the beasts that threatened them. They created effigies that we now regard as signs of aesthetic expression, despite their equal status as totems, fetishes, and conveyors of animistic energy.

A few months ago at Riley’s London studio, I was viewing a full-scale paper study of Cosmos. During our conversation, Riley suggested that I might be interested in the archaeologist Jill Cook’s account of Ice Age art – the art that humans created long before they created history. Riley was not asserting a link between shaping stone or incising ivory and arranging coloured discs on a gallery wall; yet she knows, as I know, that there ought to be a link, however obscure the chain. Human expression is human expression, then and now. Viewing Ice Age carving and cave painting, we discern a sensory vocabulary of straight lines and curves, convexities and concavities, darks and lights. We wonder at the work, yet without mystery. The ‘practical problems’ do not change, Riley has said, though she was referring to the modern Western tradition.22

At the time of my visit, Riley’s project for Christchurch had not yet received its title, or perhaps I simply failed to ask, instinctively attending to the compelling sensations rather than the possibility of definitive meaning that a title might suggest. Thoughts of the ‘cosmos’ seem to me to project into the future because, as beneficiaries of modern science, our current sense of the universe is ever expanding, even to the conceptual paradox of multiple universes. But Ice Age beings may well have had a more static sense of cosmic order than we do. Ours becomes destabilised as the progress of science displaces reassuring mythologies (granted, scientific progress constitutes our mythology). The title of Cook’s study is Ice Age Art: The Arrival of the Modern Mind – ’modern’ in the sense that we recognise the mentality as sufficiently analogous to ours for us to imagine, even to feel, its thoughts and motivations. The clearest indication of Ice Age modernity is our genetic ancestors’ capacity to create visual representations in material form: ‘History does not relate the intended messages [of the forms] but we can nonetheless appreciate the intensity of feeling generated by the act of symbolising aspects of personal, social and religious belief.’23

The symbolism to which the publication of the British Museum refers remains a matter of conjecture. How could a ‘personal’ belief come into being in prehistory? We can only apply concepts and categories of our own to a culture devoid of the kind of cultural history we take for granted. The meaning of Ice Age forms may be a question forever unanswerable. But to ‘appreciate the intensity of feeling’ is another matter. Something deeper than our pervasive romance with the ‘primitive’ establishes this emotional connection. We feel secure in referring to linear gesture, animation, proportion, spacing and even rhythm when viewing the images produced by the prehistoric ‘modern mind’. Comparing prehistoric forms to modern ones, Cook refers to a structural device of ‘disaggregating and abstracting,’ in use then as now.24 Riley’s art does not address the validity of such a relationship but speaks obliquely to the possibility of its origin in intuition, even instinct.

‘Perception constitutes our awareness of what it is to be human.’ A number of art historians – Aloïs Riegl was one, E.H. Gombrich another – have provided perception with a history, for better or worse. They are the exceptions. Our canonical history of world art is hardly one of human vision, sensation, and feeling. The conventional narrative reflects division by religion, ethnicity, nationality, political orientation, race, gender and social class, all enlisted to explain the character of particular forms of aesthetic expression – the story behind the image. While organising data by cultural division, such a history justifies and even furthers social divisiveness. Riley has never paid much heed to categories, nor to explanations based on them; she chose to learn from Seurat, a representational painter, yet became an abstractionist. Perception was the common bond. ‘My work has grown out of my own experiences of looking,’ she told Gombrich in 1992, ‘and also out of the work that I have seen in the museums and galleries, so I have seen other artists seeing.’25

No wonder that prehistoric forms of art recently piqued Riley’s interest; they are eminently, undividedly human. They embody perception, just as our art does, but as if it were the instinct of the human animal. Riley never suppresses her aesthetic instinct; she enhances it, sharpens it by exercising it in her painting. Her choices – place greyed green here, move greyed violet there, place greyed orange next – are acts of self-educated intuition. Her human instinct – devoid of history – confirms that each choice is right.