Unutai e! Unutai e!

Kāi Tahu and Anne Noble

Anne Noble Te Awa Whakatipu 2024. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

Unutai e! Unutai e!

Ko te wai anake, te au e riporipo ana ki mea roto, ki mea awa, ki te nuku o te whenua?

Aue taukuri e!

Pupū ake a Muriwai Ōwhata i a roimata He manawa piako te Papa ā-Kura o Takaroa

Waimate haere ana te waiora Kai hea rā taku ika e?

Kai hea rā te oraka mō taku iwi e!

What has transpired?

Only the rippling waters of this lake and of that river can be heard flowing across the land

Muriwai Ōwhata is over-flowing with tears

The great hīnaki of Māui, Te Papa ā-Kura o Takaroa, is like a hollow and empty heart

The life-giving waters are turning brackish and undrinkable

Where have our fresh water fish species gone?

Where are our people able to thrive?

“Who are we when we can no longer feed our manuhiri with the kai for which we are renowned?”

Anne Noble Rakahuri Ashley River Estuary, toxic algal bloom in a now degraded and depleted mahinga kai site 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Kia ora. We invite you to immerse yourself in our tribal story and reflect on this pivotal moment – one that calls us all to take action in protecting the world around us.

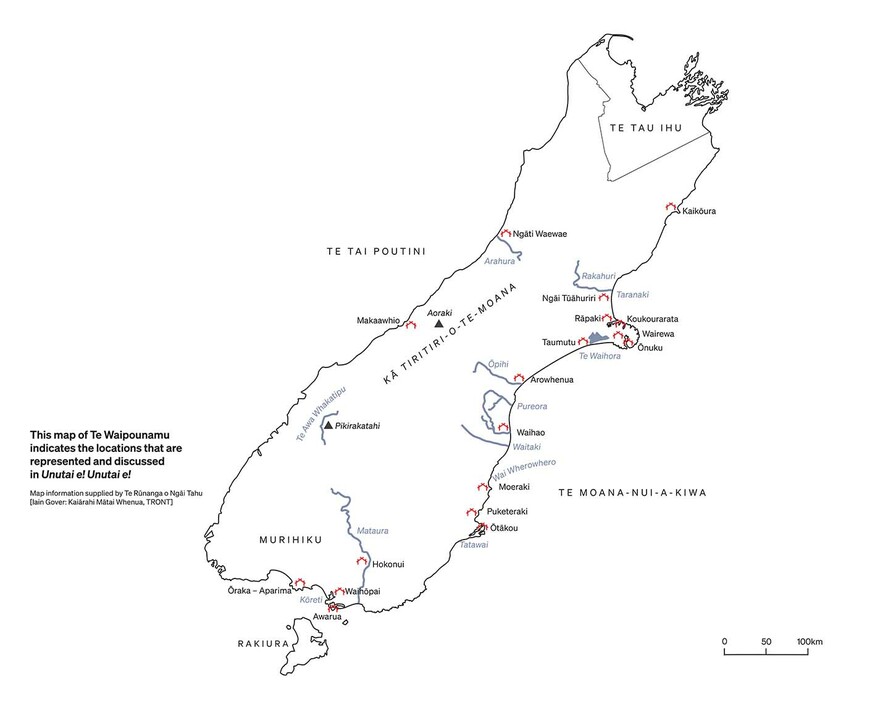

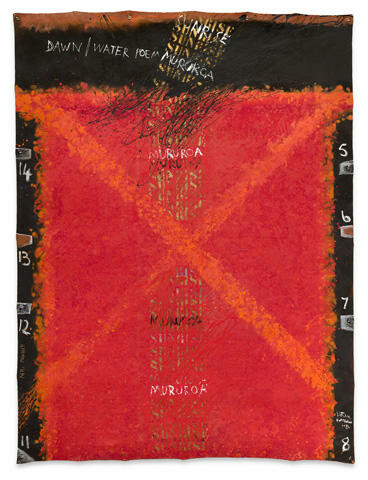

Unutai e! Unutai e! harnesses the power of contemporary art to shed light on an urgent environmental crisis: the deteriorating state of fresh water across Ngāi Tahu tribal lands. In 2020, Ngāi Tahu filed a statement of claim with the High Court in Ōtautahi Christchurch, seeking recognition of our rakatirataka over wai māori within our takiwā.

To support this claim, Te Kura Taka Pini, the division of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu responsible for the case, enlisted photographer Anne Noble to capture and document the crisis. Her role was to provide an impartial perspective – capturing our people in their chosen waterbodies while also revealing the widespread environmental degradation we witness daily across Te Waipounamu. What began as a photographic assignment evolved into an extensive visual archive, illustrating not only the devastation but also the resilience of whānau, hapū and iwi striving to restore wai māori, uphold rakatirataka, and protect mahika kai practices.

These practices are integral to Ngāi Tahu identity and survival. They compel us to ask the existential question: Who are we when we can no longer feed our manuhiri with the kai for which we are renowned?

The individuals in these photographs represent the many who have supported us over the past decade, and we are deeply grateful for their dedication, wisdom and commitment. The landscapes captured are just a glimpse of the hundreds of waterways that are taoka to Ngāi Tahu.

This exhibition begins at the pūtake mauka – our ancestral mountains, the source of fresh water. It then journeys through the polluted waterways before concluding with a vision of hope – projects dedicated to restoring balance and finding solutions.

But this is not just our story – it is a shared responsibility. The degradation of wai māori is not isolated to our takiwā; it is a crisis that affects us all. Water is the essence of life, binding us together across cultures and generations. The images you see are not just records of loss but calls to action. They remind us that with knowledge, persistence and collective effort, we have the power to heal our waters, restore our ecosystems, and honour the legacy of those who have come before us.

Without our collective efforts, the status quo remains. The future of our wai māori, our people and generations to come depends on what we do now.

“Ko wai kē mātau e kore e taea te whākai i ā mātau manuhiri ki te kai i rokonui ai mātau?”

Anne Noble Waikirikiri Selwyn River, entering Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere 2024. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Kia ora. Tomo mai koe, kia ruku mai ki te kōrero o tō mātau iwi, ā, ka āta whakaarohia tēnei wā whakahi-rahira – he mea e karaka mai nei, he mea e whakaaraara mai nei kia korowhiti atu mātau ki te kaupare i te ao e noho nei tātau.

Ka whakarērea e Unutai e! Unutai e! te whakaaweawe o te toi o nāianei kia whitikina ki tētahi āhuataka totoa, ki tētahi āhuataka mōrearea: ko te whakaparahako haere o te wai māori puta noa i kā whenua katoa o Ngāi Tahu. I te tau 2020, i te tāpaetia e Ngāi Tahu tētahi tauākī kokoraho ki te Kōti Matua ki Ōtautahi, ko tō mātau rakatirataka ki te wai māori ki roto i tō mātau takiwā te take.

Hai taunaki i te kokoraho nei, i taritaria e Te Kura Taka Pini, tētahi peka o Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu e kawea ana te mana o tēnei take, te kaiwhakaahua Anne Noble, kia whakaahuria, kia whakapūkete-hia tēnei tairaru pōautinitini. Ko tāhana, he whakarato i tētahi tirohaka matatika – Ka whakaahuria tō mātau iwi ki ō rātau ake wai, kai huraina ana te rakiwhāwhātaka o te tūkino ki te ao tūroa e kitea ana e mātau puta noa i Te Waipounamu rā atu, rā mai. I tīmata hai hinoka whakaahua, ā, i kukune ake ki tētahi pūraka wharaurarahi ā-kanohi, ehara i te mea e whakaaturia ana te whakamōtī anake, ekari he whakakiteka hoki o te kiri tuna o kā whānau, o kā hapū, o kā iwi e whakapau werawera ana ki te whakamāori anō i te wai māori, ki te tū rakatira anō kā rakatira, ā, ki te pupuri tou ki te mahika kai.

Ka noho ēnei mahi hai pūtake māria ki te tuakiri me te oraka toutaka o Ngāi Tahu. Ka ākina tātau te ui atu i te pātai tauoraka: Ko wai kē mātau e kore e taea te whākai i ā mātau manuhiri ki te kai i rokonui ai mātau?

Ko rātau kai ēnei whakaahua, ka noho hai kanohi o te tini mano i noho hai tuarā mō mātau i te kahuru tau ko hori, ā, e whakamānawanui ana mātau ki tā rātau ū titikaha, ki ō rātau kura, ā, ki tō rātau manawa tītī hoki. He karipihaka mata anake kā horanuku ko whakaahuaria o kā taoka arawai e hia rau nei o Ngāi Tahu.

Ka tīmata te whakaaturaka nei ki te pūtake mauka – ko ō mātau mauka tipua, te matatiki o te wai māori. Kātahi ka whāia ka ara ki kā arawai parakino i mua i ā rātau putaka atu ki te arokanui o tūmana-ko – ko kā hinoka e ū tou ana ki te whakatikatika, ki te whakataurite, ā, ki te whai rokoā anō hoki.

Ekari, ehara tēnei i tā mātau kōrero anake – he haepapa tahi tēnei o te katoa. Kāore te whakapar-ahako o te wai māori i tētahi pāka kino ki tō mātau takiwā anake; he parekura ka pā ki te katoa. Ko te wai te toto o te whenua, ko te whenua te toto o te takata e tuia nei tātau ki a tātau, puta noa ki ahurea kē, ki whakatipuraka kē. Ehara i te mea he mauhaka kōrero o kā mea ko karo, ekari ka karakahia nei mātau ki te poupourere. Kia maharatia mai, mā kā kura o nehe, mā te manawa tītī, mā te tū pakihiwitahi te oraka māria o ō tātau wai, te mana ki te whakarauora i te ao tūroa, ā, te whakarakatira i kā tukuka ihotaka o rātau mā.

Ki te kore tātau e tū pakihwitahi ana, ka mau tou ki taua āhua tou. Ko te anamata o tō tātau wai māori, o tō tātau iwi, o kā uri whakatipu ka whakawhirinaki atu ki ā tātau mahi o te nāia nei.

Gabrielle Huria (Ngai Tahu, Ngai Tuahuriri)

Chief executive Te Kura Taka Pini, Tumu Whakarae Te Kura Taka Pini.

Whakamāori: Tēnei te Ruru Ltd.

Rakahuri Ashley River

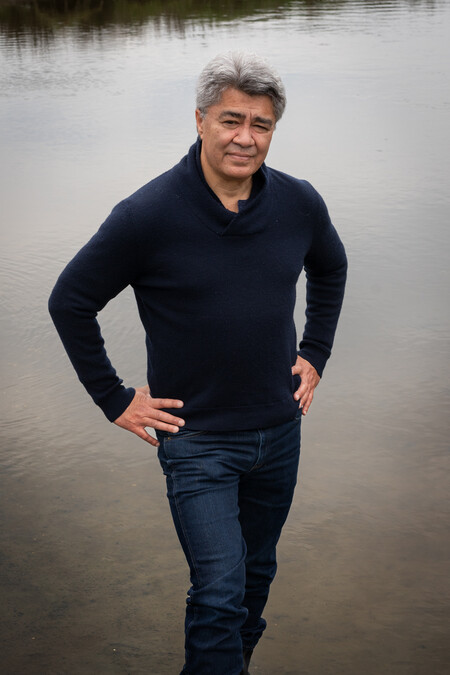

Te Maire Tau (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri)

Upoko o Ngāi Tūāhuriri, first plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae Tuatahi ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble West Lees Valley looking towards the Puketeraki range, the source of the Rakahuri Ashley River 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

What stands before me is a river that’s a shadow of its former self. People accept this as the Rakahuri today, but that’s not how it was. The name Rakahuri refers to the fact that the waters were strong enough to pull the trees out of the banks. Raka means to pull the stumps – to draw them out – and huri is to turn, so they’d be turned over and over by the time they got to the mouth. And that’s really a commentary on the power of the river, because it was a proper river with a strong flow.

One of the interesting things about the Rakahuri is that when we were young, our community would live on the river. We would camp there to get food, and we were permitted to live there through a Land Court Order that applied to our reserves on the river and some of the tributaries.

Tuahiwi families would relocate to these reserves in August, and they would camp there right through to November, getting whitebait. Every family had its hut and what you had was a thriving community living along the river. There might have been about twenty huts and houses with all the kids running around. They’d catch the school bus from there. They really did live off the river and it was all maintained and looked after.

Many New Zealanders wouldn’t know this, but in the 1980s we were forcibly relocated by the County Council. They removed our huts and prohibited any more camping on our river. This was despite a legal order from the courts that permitted us to do so. Our people were removed, and those camps no longer exist.

Now what we’ve got is the extinguishment of a river. The Rakahuri starts inland, it becomes a network of farm drains, water is taken out of the river for irrigation. Farm run-off is poisoning the waters of the tributaries and the lagoons with toxic silt and effluent, the fish life is under threat, the bird life is under threat – the environment is under threat.

The Rakahuri Ashley is an indicator of the slow destruction of all our riverways that is happening right now before our eyes. These are not the Canterbury Rivers that our ancestors knew and that the early settlers knew. What we are looking at is a wasteland. What should be sand and gravel is like a septic tank pit. There is faecal content in it. You feel ill eating the food from here.

We used to get watercress along the creeks and tributaries – but look at it. You wouldn’t get watercress out of this. I have, and it stinks. You can’t eat it and you certainly wouldn’t put it in a hāngi.

What’s happening here is that we are all bearing the cost of the environmental impacts of intensive dairy farming. We want to save these rivers – for the tribe, for Christchurch, for Canterbury and for the entire New Zealand public.

Anne Noble Te Maire Tau (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri) Rakahuri/ Ashley River Estuary 2023 Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Ko tēnei kai mua i ahau, ko tētahi awa, he tohihī noa tēnei o te awa tārere i rere i kā wā o mua. Whakaae ana a ētahi ko te Rakahuri i ēnei rā, ekari, ehara tērā tōhona āhua i mua. Hākai ana te ikoa, Rakahuri, ki te au kaha o te wai, e pērā ana te kaha i tōia kā rākau i te pārekareka. Ko te ‘raka’, ko te huhutitaka atu o kā kōtumu o te rākau, ā, ko te ‘huri’ ko te mahi a te awa, e takahurihuri ana i kā rākau tae noa atu ki te pūwaha o te awa. Kōia he takika kōrero mō te kaha rere o te wai o tēnei awa, i te mea he awa tūturu, he au kaha ōhona e rere ana.

Ko tētahi o kā āhuataka pārekareka mō te Rakahuri, nō mātau e taitamariki ana, e noho ana tō mātau hapori ki te awa. Ka noho puni mātau ki te mahi kai, ā, i whakaaetia tā mātau noho e tētahi Ture Kōti Whenua i tū ki ō mātou whenua rāhui ki te awa, ki ētahi hoki o ōhona kautawa.

Ka nuku atu kā whānau o Tuahiwi ki ēnei whenua rāhui i te Whā, ā, ka noho puni rātau tae noa ki te Whitu e hao īnaka ana. I ia whānau tō rātau ake wharau, ā, he hapori tōnui e noho ana ki te roaka o te awa. Kai te takiwā pea o te 20 wharau me kā whare, ā, e omaoma noa ana kā tamariki. Ka kakea te pahi kura i reira. Ko te awa te oraka tūturu o aua whānau, ā, i tiakina, i atawhaitia ngā mea katoa.

Ko te nuika pea o kā kiritaki o Aotearoa, kāore i te mōhio ki tēnei, ekari i te kahuru tau 1980, i kāhakina atu mātau ki wāhi kē e te Kaunihera. I turakina ō mātau wharau, ā, i rāhuitia te noho ā-puni ki tō mātau awa. I pēnei rātau, ahakoa he ture nō te kōti i whakaae ki tā mātau noho ki reira. I kawea atu mātau, ā, ko karo kē aua tōpuni i ēnei raki.

Ināianei, ko te mea ki mua i a mātau, ko te whakatīneitaka o tētahi awa. Kai tuawhenua te hikuwai o te Rakahuri, ā, ka huri hai whatuka waikeri ahuwhenua, ko tako te wai i te awa ki te hāwaiwai i kā ahuwhenua. Mā te wai tuhene nō kā pāmu kā kautawa me kā hōpua wai e paitini ai ki te parakiwai tāoke, ki te parapara tāoke, whakaraerae haere ana hoki kā ika me kā manu - ko te taiao tou e whakaraerae haere ana.

Ka noho mai ko te Rakahuri hai paetohu o te orotā ukauka o ō mātau arawai katoa kai mua tou i tō mātau aroaro. Ehara ēnei i kā awa o Kā Pākihi-whakatekateka-a-Waitaha i mōhiotia e ō mātau tīpuna, i mōhiotia rānei e te takata pora. Kai mua i a tātau he whenua tuakau. Te tikaka ia he onepū, he kirikiri, ekari he kura rua parakaingaki kē. He hamuti kē ki roto. Ka māuiui koe i te kai i ngā kai nō konei.

I mua rā, i kohia ā mātau wātakirihi i ngā awaawa, i nga kautawa – ekari, titiro. E kore rāia e kohi wātakirihi i konei. I pērā au, e, he hauka. E kore e taea te kai, e kore rāia e tukuna ki te umu.

Ko te mea e pahawa nei, mā mātau te utu o kā pāka kino ki te taiao o kā pāmu ahumīraka kakati e kawe. Kai te hiahia mātau ki te whakaora i ēnei awa, mō te iwi, mō Ōtautahi, mō Waitaha, ā, mō te marea katoa o Aotearoa.

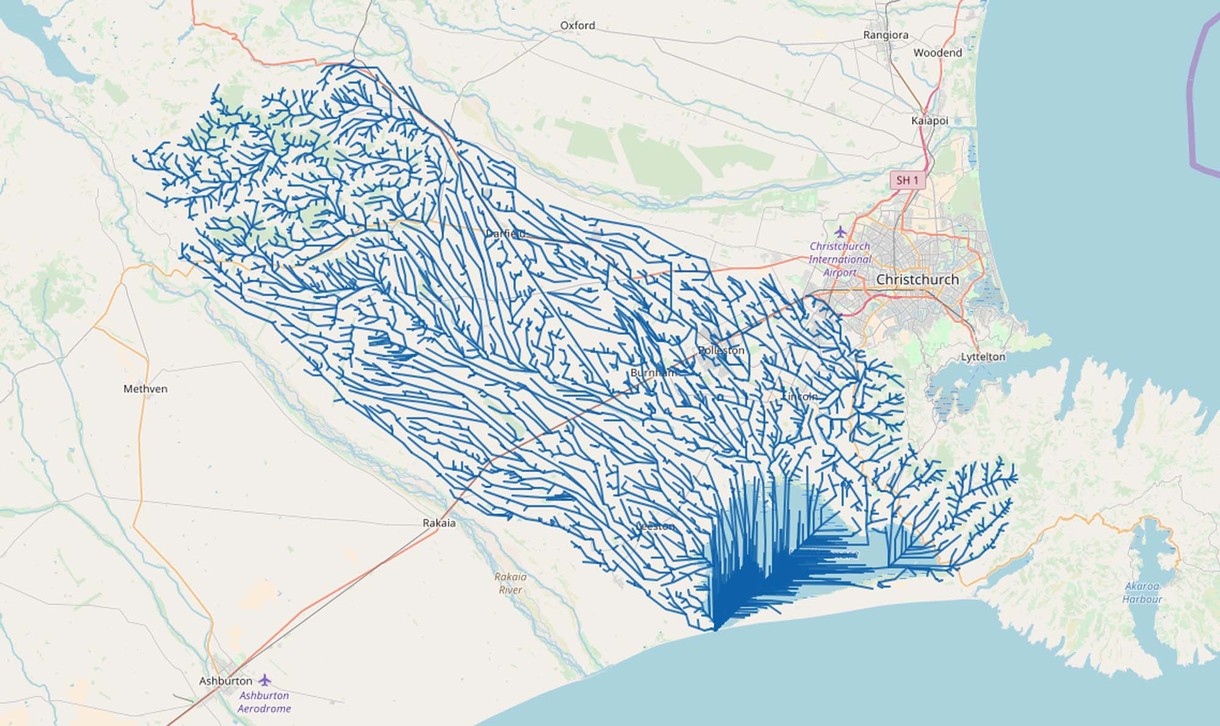

Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere

Dr Elizabeth Brown (Kāi Tahu, Taumutu)

Chair, Te Taumutu Rūnanga / Toihau o te Rūnanga o Taumutu; executive director, Office of Treaty Partnership University of Canterbury / Kaihautū Matua, Te Tari Mana Tiriti, Whare Wānanga o Waitaha; plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble Huritini Halswell River, entering Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere 2024. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

I remember my taua, Aunty Ake, talking about how the lake was clear enough that you could see the shingle on the bottom. When we were growing up it was never a consideration that you couldn’t just swim in the lake, or that you needed to think carefully about how healthy the fish were. Nowadays the number of times there are restrictions on accessing the water because of toxic algae increases every year, which means we can’t have total confidence that we can do our mahinga kai practices safely.

The biggest change in my lifetime is the quality of the water. Te Waihora has become the polluted repository at the end of all the rivers, tributaries and waterways that drain into it through the farmland around it.

Taking a ki uta ki tai approach, we can’t just think about Te Waihora, we must think about how all the rivers, tributaries and waterways feeding into Te Waihora impact upon water quality. While Ngāi Tahu had the lakebed returned as part of our treaty settlement, we got it back in a very degraded state. We have nitrates and phosphorus feeding into the lake, as well as the legacy of phosphorus and nitrogen sediment within the lakebed that will cost millions of dollars to remedy.

Eighty percent of the wetlands around Te Waihora have gone, and they were a key supporter of water quality and our mahinga kai practices. Originally the lake was four metres deep and when you drove through Lincoln, the waters of Te Waihora would have been lapping on the shores of the town. That tells you how much the lake has shrunk and the extent of wetland loss.

Currently, when the lake level rises to about 1.3 metres there is a risk of farmers’ land around the lake edge being inundated. This triggers a discussion about the opening of the lake, but we would prefer the lake is kept at around about 1.8 metres to improve the quality and quantity of the water and assist us to carry out our mahinga kai practices. We also need some wetland restoration to restore mahinga kai habitat and to address the turbidity of the water and the suspension of legacy nitrogen and phosphorus in the lake. So, there is a clash of cultures to negotiate. How do we reach a balance between our values and needs and the needs of the farming community when higher lake levels and wetland restoration projects impact on the economic viability of land at the perimeter of the lake?

Our vision for wetland restoration is to restore the mauri and the mana of Te Waihora. Te Waihora is our identity, it’s who we are. It is part of the life of Taumutu, and degradation of our lake reflects on us and affects our identity as Te Ruahikihiki. It is the environment that shapes our culture – not the other way around. Without the wetlands, we no longer have the access to our mahinga kai practices and that then changes us significantly as a people.

Anne Noble Elizabeth Brown (Kāi Tahu, Taumutu), Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Mahara ana au i taku taua, Hākui Ake, e kōrero ana mō te mārama tou o te wai o te roto, i taea te kite i te kirikiri ki te takere. I a mātau e tipu ana, kāore i paku whakaaro mō te kaukau ki te roto, ki te oranga rānei o ngā ika. Engari anō ēnei rā, te hia nei ngā wā ka rāhuitia te toronga atu ki te wai i te mea ka piki tou te nui o te pūkohu paitini i ia tau, hai aha? E kore rāia e whakapono e taea ana e mātau te puta haumaru atu ki te mahinga kai.

Ko te panonihanga nui i te wā ki a au, ko te hekenga o te horomata pū o te wai. Ko huri Te Waihora hai purunga parakino kai te pūwaha o ngā awa, o ngā hikuawa, o ngā arawai e rere atu ana ki reira i ngā pāmu e karapotia nei te roto.

Kai tā mātau aronga ko ‘Uta ki Tai’, ehara i te mea ka whakaaro anake mō Te Waihora, engari me whakaaro hoki mō te rere iho o ngā awa, o ngā hikuwai, o ngā arawai katoa ki Te Waihora me te pānga o aua wai katoa ki te horomata o te wai i reira. Ahakoa i whakahokia te takere o te roto ki a Ngāi Tahu i te kerēme, i whakahoki parangetungetu mai. He pākawa ota, he pūtūtaewhetū e rere atu ana ki te roto, ā, kai te parakiwai ki te takere o te roto kē he pūtūtaewhetū, he pākawa ota nō ngā ngahuru tau i mua, e hia manomano tāra te utu ki te whakatika.

Waru ngahuru ōrau te nui o ngā repo o Te Waihora ko ngaro, ā, he mea whakaora wai matua, he wāhi mahinga kai anō hoki aua repo. I ngā rā o mua he whā mita te hōhonu o te roto, ā, ka hautū waka koe ki Lincoln, ko ngā wai o Te Waihora ko paki atu ki ngā tahataha o te tāone. Mā reira koe e mōhio mō te hekenga mārie o te wai, me te korahi o te whakatahenga o ngā repo.

I nāianei, ka piki ana te kārewa o te roto ki runga ake i te 1.3 mita, ka waipukehia te whenua o ngā kaipāmu kai ngā pārengarenga o te roto. Mā konei ka tīmata te kōrero mō te whakapuare i te roto, engari anō mātou, e pīrangi ana kia 1.8 mita kē te hōhonu o te wai, kia ora pai ai te wai, kia nui pai ai te wai, e taea ana e mātau a mātau mahinga kai te tutuki. Kai te hiahia hoki ki te whakarauora anō ngā repo, kia pai ai te mahinga kai, kia ora ai te whaitua, ā, kia kore nei e ehu tou ai te wai, kia māmā ake te kawe i te pākawa ota, i te pūtūtaewhetū i te mauroa ki te roto.

Heoi anō, he tukinga tikanga hai matapaki mā te Māori me te Pākehā. Ka pēhea e whakataurite ai ngā uara, ngā matea me ngā matea o te hapori ahuwhenua ina e pā kino atu ai te pikinga o te hōhonu o te roto me ngā hinonga whakaora repo ki te oranga toutanga o te ōhanga o te whenua kai te āwhiotanga o te roto?

Ko tō mātau arongapū ki te whakarauoratanga mai o ngā repo, ko te whakaora anō i te mauri me te mana o Te Waihora. Ko Te Waihora tō mātau tuakiri, ko mātau tou ko Te Waihora. Ko Te Waihora te oranga o Taumutu, ā, ko te āhua parangetungetu o te roto, he mea whakahuritao ki a mātau, ā, ka pātahi mai ki tō mātau tuakiri hai uri o Te Ruahikihiki. Ko te taiao kē te kaiwhao o tā mātau tikanga – ehara i te mea ko te tangata. Ki te kore he repo, kāore he mahinga kai, ki te kore he mahinga kai, ka tino rerekē rawa atu nei mātau hai tangata.

Taranaki Stream Te Awaawa o Taranaki

Gabrielle Huria (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri)

Chief executive Te Kura Taka Pini, Tumu Whakarae Te Kura Taka Pini.

Anne Noble Dominic Murphy, Taranaki Stream, Whānau inanga site 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

The Taranaki was always a very gentle place to whitebait. It’s good for the older people because they’re not having to battle the winds and the strong incoming tides like the younger men do out at the mouth of the Rakahuri.

Our family wakawaka is here on this part of the Taranaki. My grandfather and his brothers built one of the early floodgates and our whole family history is connected to the Taranaki and the Rakahuri. We are responsible for maintaining the wakawaka in the season. You look after it. You go down pre-season and make sure everything’s tidy, otherwise you lose your rights to be there. My cousin held the rights after his mother and grandfather died and when he recently had a stroke, my family have now taken over that responsibility.

The 2024 season was the first time in our whole family history that we couldn’t whitebait here. The water is foul. It is too dirty. Some brave relations still go there and whitebait, but I know too much about the science and what is in that water to risk it.

The hard thing for me personally is that every time we fish here, we know we are doing the same thing that our ancestors have done for generations. This is who we are. But if we can’t practice our mahinga kai, and if we can’t pass our traditions on to our kids because there’s nowhere to fish anymore, who are we? And I don’t want to be part of a generation that saw the destruction of our culture and our values. We are facing an existential crisis, and the reason we are taking a claim to the High Court is to fight for all we are losing – not only for us. Our fight is for everyone.

Consecutive governments have failed all the people of the South Island. Whereas fifteen years ago our rivers were clean, from the eastern seaboard to Otago and Southland, they’re genuinely filthy, overallocated for irrigation and unswimmable, and it’s getting worse every year.

Who said this is acceptable? It’s not acceptable to us. Pollution and environmental destruction are happening fast. The decline in the quality of our waterways has crept up on us since agriculture was enabled to transfer to intensive dairying on a huge scale. No one is holding those responsible for the resulting environmental degradation to account.

For the last fifteen years we’ve been putting our efforts as a tribe into researching how these catchments work. We marry our collective traditional knowledge with the science. We are thinking carefully and know that things must change to ensure future generations can benefit in the way we have. The reason this work is so important to us as a tribe is so we can be the conscience that holds the government to account. The Taranaki was once a beautiful little river. When I can smell a clean river, I know where I am, but this river smells sick and sad. If our Taranaki had feelings – and I think it does – I wonder what it might be telling us?

Anne Noble Gabrielle Huria (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri), Taranaki Stream. Whānau inanga site 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

He wāhi māmā te Taranaki hai wahi hao īnanga. He pai ki ngā taua me kā poua i te mea kāore he hau e pūawhe kino ai rātau, ā, kāore he tai pari e whakararu ana i te tangata pēnei i ngā taitamatāne kai te waha o te Rakahuri.

Kai konei, kai tēnei wāhi, te wakawaka o tō mātau whānau. Nā taku poua rātau ko ōhona tuakana-taina tētahi o ngā ahuriri tuatahi i hanga, ā, ko te kōrero tuku iho o tōhoku whānau katoa ko herea ki te Taranaki, ā, ki te Rakahuri anō hoki. Nō mātau te haepapa whakapaipai i te wakawaka i roto i te tau. Ka tiakina. Ka haere atu i mua i te tīmatanga o te tau kia mōhio ai koe, he pai rānei, he tika rānei, ki te kore, ka ahimātao tō ahi. Nō taku karangatahi te mana i te matenga o tōhona hākui, o tō mātau poua hoki, engari inatata nei pāngia ia e te ikura roro, nā reira, nō tōhoku whānau ināianei taua haepapa nui.

Ko te tau 2024 te tau tuatahi i te kōrero tāhuhu o tōku whānau kīhai i taea te hao īnanga ki konei. I te pīrau te wai. He paru rāia. Ka haere tou ētahi whanaunga mātātoa ōhoku ki te hao, engari nā taku mōhio ki te pūtaiao, ki ngā mea kino kai te wai, kāore au i te hiahia tūpono atu ai ki taua kino.

Ko te mea uaua ki a au ake, ia wā ka puta ki te hī, ki te hao rānei, kai te tino mōhio mātau e mahia ana e mātau te mahi tou a ō mātau tīpuna nō ngā reanga e hia kē nei ki mua. Ko mātau tēnei. Engari ki te kore e taea te mahinga kai te mahi, ā, ki te kore e taea te tuku iho i ā mātau tikanga ki ā mātau tamariki i te mea kāore he wāhi e pai tou ana ki te mahi ika, ko wai hoki ia mātau? Kāore au i te pīrangi, ki tōhoku reanga tou, te kite atu i te orotā o ā mātau tikanga, o ō mātau uara. He tairaru tauoranga kai te aroaro, ā, ko te take e kawea atu ana e mātau tā mātau kaupapa ki te Kōti Matua, ko te whawhai ki te pupuri ki aua mea e ngaro haere ana – ehara i te mea mō mātau anake. Mō te katoa tēnei whawhai.

Kāwana atu, kāwana mai ko mūhore tā rātau tiaki i ngā tāngata o Te Waipounamu. Ngahuru mā rima tau ki mua, he mā ngā awa katoa, ināianei, mai i te ākau rāwhiti, tae noa ki Ōtākou, ki Murihiku, he paru tūturu, he nui rāia te whakaratonga hāwai, e kore e taea te kauhoe, hai ia tau e piki ake ana te kino.

Nā wai ia nei tēnei āhua i whakaae? Ehara nā mātau. He tino wawe te parahanga, me te orotānga o te taiao. Hūrokuroku ana te paru haere o te horomata o ngā arawai, ko paru ake nei, ko paru ake nei i te whakaaetanga o te mahi ahuwhenua ki te whakawhiti atu hai pāmu ahumīraka kakati, hai pāmu kau korahi. Kāore tētahi i te whakawhiu i te hunga nā rātau te taiao i parangetungetu.

Nō ngā tau ngahuru mā rima, i te āta whai, i te ngana, hai iwi, ki te rangahau i te rerenga o ēnei riu hikuwai. Kai te āta whakaaro, kai te mōhio hoki mātau, me panoni ā tātau mahi kia whai hua ai ngā uri whakaheke pēnei i a mātau. Ko te take he whakahirahira rāia te mahi nei ki a mātau kia taea ai e mātau te tū hai ngākau whakawā e whakatikaina ai te kāwana.

Ko te Taranaki i mua, he awa ātaahua. Ka rongo ana au i te kakara o te awa mā, kai te mōhio au kai hea au, engari ko tēnei awa nei, he haunga kē, he māuiui. Ina he whatumanawa tō te awa nei – ko tāku e whakapae nei, āe he whatumanawa tōhona – he aha kē pea āhana kōrero mai ki a mātau?

Taranaki Stream

Maru Tau (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri)

Anne Noble Taranaki Stream. Water quality and surrounding environment impacted by toxic farm runoff into a whanau inanga site 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

I remember when the water here used to be clean and clear. Underneath where that red tree is, I could see the clouds of whitebait coming in around the corner. I could see the stones in the water, the pebbles, the whitebait pumping. Everything was crystal clear.

Probably one of the best markers for change is that tree. It should be a bright-red colour, but now it’s like a balding middle-aged man losing his hair. It used to be the most beautiful red tree at this time of the year and it’s dying – like the rest of it.

It was in 2014–15 that things really started to change. I remember the day this brownness in the water started. I remember seeing it and thinking, that’s odd. It started to look like someone had poured a big, strong pot of tea into the water, and there were these brown streaks coming through it. The following year there were more and more brown streaks, and as the years go on that brown has become the most dominant colour. One year it’s clear, the next year it’s one-eighth tea, the next year it’s quarter tea, and then it’s half tea – like a paint mix, and what we have now is triple-tea when what we used to have, was clear water.

Every time the tide comes in and goes out again, it stirs up the silt, the nitrates and the cow shit on the bottom of our river and that settles on the eggs of the whitebait. So, if you’ve been white baiting for centuries and you’ve had clean water, then, all of a sudden – since 2015 – you’ve got two tides a day coming in, with silt and nitrates that sits on your eggs. My guess is your eggs probably won’t hatch as well as they used to in fresh, clear water. When I lift my net up now it’s full of cow shit. If it smells like cow shit and it looks like cow shit, it’s gotta be cow shit, doesn’t it? And you don’t need to be an expert to figure that out.

They are talking about wanting to shorten the whitebait season to fix the problem, but you can shorten the season or even stop the season for the next 10 years, but it’s not going to help. The real problem is the habitat. It is the quality of the water that is killing our habitat, and that’s what has to be fixed. Intensive grazing and farming by the dairy industry can’t be helping. If you were to kill every single cow, I guarantee that maybe in 10 or 20 years this river would be back to being clean. But if you were to stop the season for the next 10 or 20 years, that isn’t going to help.

At night I always look at that tree as my marker, and it’s looking worse and worse every year.

Mahara nei au te wā i te tino mā, i te tino mārama te wai o konei. Kai raro i te rākau whero ki reira, i kitea tētahi pōkai īnanga e haere mai ana i te kokonga rā. I taea te kitea ngā kōhatu, ngā pōhatuhatu, me te rere tou o te īnanga. Tārake ana te kitea.

Koia pea tētahi o ngā tohu pai o te huringa o te ao, ko taua rākau. Te tikanga ia he kura muramura te tae, engari ināianei, ko te koroua e pākira haere ana tōhona rite. I ngā rā o mua, he rākau ataahua rirerire i tēnei wā o te tau, ā, mate kē ana te āhua – pēnei i tēnei wāhi katoa.

I te tau 2014-2015 i te tīmata ngā hurihanga nui. E hoki ana aku whakaaro ki te rā i te parauri haere te wai. Mahara ana taku kiteka atu, ā, i toko ake te whakaaro, hanga rerekē ana tērā. Te hanga nei ko riringihia e tētahi he tīpata nui o te tī uriuri ki te wai, ka puta mai ētahi tarapī parauri. Hai te tau e whai ake, i te piki ake hoki te nui o ēnei tarapī parauri, haere nei ngā tau ko te parauri kē te tae o te wai. Hai tētahi tau he mārama, hai te tau e whai ake he tahi hau waru tī, he tau anō, he tahi hau whā te tae tī, kātahi ko te haurua tī – pēnei i te peita, ā, kai te awa ināianei he toru hau whā tī, engari i ngā rā o mua he wai mārama kē.

Ia wā ka pari mai te tai, ka timu hoki te tai, ka kōrorihia te parahua, te pākawa ota me te tūtae kau kai te takere o te awa, ā, ka tatū ki runga i ngā hua īnanga. Heoi anō, ina i te hao īnanga koe i ngā rautau ko pahure mōhoanoa nei, he wai māori kē te wai, kātahi, ka puta mai i te kore – nō te tau 2015 – e rua kē ngā tai i ia rā, me he parahua, he pākawa ota ka noho ki runga i ō hua īnanga, e kore aua hua īnanga e puta mai, pērā i ngā tau i mua i te wā e tino māori te āhua o te wai. Ka hiki ana au taku kūpenga, ko kī ki te tūtae kau. Mēnā he rite te haunga ki te tūtae kau, he rite te hanga ki te tūtae kau, he tūtae kau kē tēnā nē? Ehara i te mea me he mātanga koe ki te kite i tērā.

Kai te kōrero rātau mō tā rātau hiahia ki te whakapopoto i te tau īnanga kia tika ai te mate, engari e taea ana te whakapopoto te tau, ka rāhuitia pea te tau mō ngā tau ngahuru e heke mai nei, ehara tērā i te rongoā ki te aha. Ko te mate nui, ko te whaitua. Ko te wai parangetungetu tērā e patua ana te whaitua, ā, me whakatika i tēnā. Kāore te kaikai tuhene, te mahi ahuwhenua kakati o ngā pamū huamiraka rānei e āwhina ana. Ina ka patu koe i ngā kau katoa, ko taku kī taurangi nei, hai te ngahuru tau, te rua ngahuru tau rānei te awa e ora haere ai. Engari, ina ka rāhuitia ngā tau hao īnanga mō ngā tau ngahuru, rua ngahuru rānei, e kore e aha e tutuki.

I te pō, rite tou taku titiro atu ki te rākau rā hai tohu māhaku, a ia tau ka hē, kātahi ka hē kē atu.

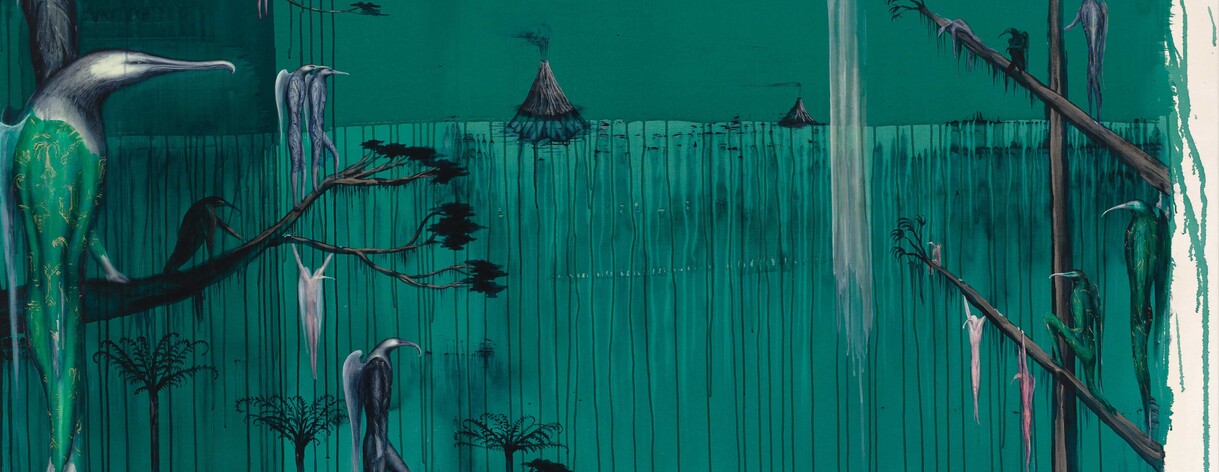

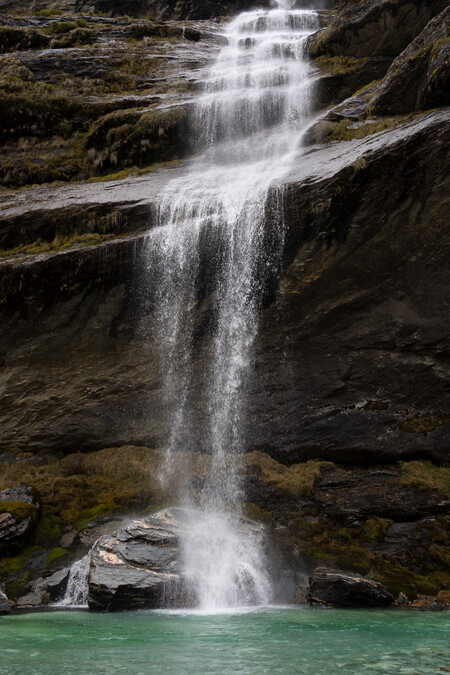

Te Awa Whakatipu

Paulette Tamati-Elliffe (Kāi Te Ruahikihiki, Kāi Te Pahi, Kāti Hāwea)

Tumu/Manager, Kotahi Mano Kāika – Kāi Tahu reo revitalisation strategy / Rautaki whakarauora i te reo o Kāi Tahu.

Tūmai Cassidy (Kāi Te Ruahikihiki, Kāi Te Pahi, Kāti Hāwea)

Toa Taiao – Te Rūnaka o Ōtākou.

Anne Noble Pūtake-mauka Wai o te Pikirakatahi 2024. Digital print, pigment on paper Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

These images evoke for me a sense of timelessness. It is the purity of the wai, coming down the mauka, feeding into our awa. From the beginning of time, our mountains have provided the source of water. So, when I am here that’s how I am thinking, not about time on a human scale, but of timelessness and the antiquity of our creation narratives.

We come from the atua, and this living connection ensures that we’re part of our environment. Rakinui, Papatūānuku and all the elements are included in our personification of nature. They are tīpuna. They are atua. They are deities that we connect with so that everything in our environment is connected through whakapapa.

While I am mindful of the intergenerational connection back to our ancestors and what these places meant for them, I’m also mindful of our history here, of our disconnection from these places, and the desire for us to re-establish and re-strengthen our connection to them.

When you see the purity of the headwaters here and the worsening degradation further downstream you see the impacts of exploitation and commodification of our natural resources and the lack of care or responsibility for them.

For generations these places were lived in by our ancestors. Many of these places carry ancestral names of our tīpuna, narratives of voyages. They carry the history of our people. These are the places where they would harvest their kai. This was a huge part of our tribal economy which meant much more than transactional values – it was a continuation of our lifeways ensuring the intergenerational succession of knowledge embedded in our practices.

Whakapapa isn’t just about the human realm. Whakapapa underpins our identity and even more so for our younger generation as we’ve restored our language and our belief systems that were eroded through Christianity – one of the many impacts of colonisation.

Mahika kai is the backbone of our identity. Knowing our practices and maintaining these practices is who we are and why these places are so important to us. Even though our villages are largely on the coast, it’s through these awa that we are connected to the inland areas that are a part of our tribal estate.

Our younger generation know the importance of restoring our place within our environment and through this worldview they know that there are practices that need to be adhered to. Understanding the seasons of our kai and our interaction with the practices of harvesting mahika kai. These responsibilities are serious, and you don’t breach them, because we know the impact it will have not only on those species but on ourselves.

I certainly feel this when I’m doing the mahi that we’re doing. I’m certain that our tīpuna had thoughts of us in their time, just as much as I have thoughts about my future generations in our time – and this is why I’m compelled to act responsibly for my future generations.

Anne Noble Tūmai Cassidy (Kāi Te Ruahikihiki, Kāi Te Pahi, Kāti Hāwea) and Paulette Tamati-Elliffe (Kāi Te Ruahikihiki, Kāi Te Pahi, Kati Hāwea), Te Awa Whakatipu 2024. Digital print, pigment on paper Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Mā ēnei whakaahua toko ake ai te ake ake o te hurika o te ao. Ko te wai horomata e rere iho mai i kā mauka, rere atu ana ki ō mātau awa. Nō mai rā anō, ko ō mātau mauka te pūtake, te rau matatiki o te wai. Nā reira, i a au i konei, koia te rere ō ōhoku whakaaro, ehara i te mea e whakaaro ana au mō te ao o te takata, ekari ko te ao herekore o te ake ake, ko kā kōrero orokohaka nō tua whakarere.

Nō kā atua mātau, ā, ko te honoka ora ka mau tou, ka here tou nei mātau ki tō mātau taiao. Ko Rakinui, ko Papatūānuku, ko kā momo āhuataka katoa o te ao tūroa ko whai wāhi i tā mātau whakatakata i te taiao. He tīpuna. He atua. Ko rātau kā atua e tūhonohono ai ki a mātau, mā te whakapapa e whiri tou ai mātau ki tō mātau taiao.

Maharatia nei e a au te hono o te kāwai whakapapa ki ō mātau tīpuna me te hiraka o ēnei wāhi ki a rātau, maharatia hokitia ō mātau ake kōrero ki konei, te motuka o te here ki ēnei wāhi, te kōiko o te manawa ki te noho anō ai, ki te aukaha anō ai ā mātou here ki ēnei wāhi.

Ka kite ana te urutapu o kā hikuwai ki konei, te paraketuketu haere i te reremuri o te awa ka kitea hokitia kā pāka kino o te kaiapo, o te whakatauhoko o te ao tūroa, i ruka tou i te manawa kore, i te haepapa kore.

Reaka atu, reaka mai, noho atu ana ā mātau tīpuna ki konei. Ko korowaihia toutia te whenua ki kā ikoa o kā tīpuna, ki kā kōrero o ā rātau haereka hoki. E kawea ana te kōrero tāhuhu o tō mātau iwi. He wāhi mahika kai. He wāhi nui tēnei ki te ōhaka o te iwi, ehara i te mea ko kā uara kurutete anake, he nui ake i tēnā – he haereka toutaka o kā ara whakaora, e mātua whakaritea ana te tukuka ihotaka o te mātauraka, ko tuia ki te kaka o te mahi.

Kāore hoki te whakapapa e hākai noa ana ki te ao takata. Ko te whakapapa te tūāpapa o tō mātau tuakiri, he nui anō ake te mana o te whakapapa ki te tuakiri o ō mātau uri i a mātau e whakarauora anō ai te reo, me kā kawa o mua i whakahoroa e te whakapono Karaitiana – tētahi anō o kā tini pāka kino o te tāmitaka.

Ko te mahika kai te tuahiwiroa o te tuakiri. Ko tō mōhio ki kā mahi a ō tīpuna, tō pupuri tou ki aua mahi, koina te honoka ki te tuakiri, ā, koina hoki te take he wāhi tapu ēnei wāhi ki a mātau. Ahakoa kai te takutai te nuika o ō mātau kāika, mā kā awa mātau e here ai ki tuawhenua ki te roaka ake, ki te whānuitaka ake o te rohe o ō mātau hapū.

Kai te mōhio te ata o tūmāhina ki te hiraka o te whakahokika atu ki te wāhi i tū ai ō mātau tīpuna ki te taiao, ā, mā tēnei tirohaka Māori e mōhio ana rātau he mahi hai mahi, he mahi hai pupuri. Ko tō mātau mārama ki kā tau kai, me tā mātau taunekeneke ki ā mātau mahika kai, he haepapa nui, he haepapa ōkawa, ā, ka kore rāia e takahi, i te mea, e mōhio kē nei mātau te pāka kino ka pā atu ai ki kā koiora, ā, ki a tātau anō hoki.

Ka tino roko au i tēnei āhuataka i a au e mahi ana i ā mātau mahi. Whakapono nei au, i te whakaarohia toutia mātau e ō mātau tīpuna i te wā i a rātau, pēnei i ōhoku whakaaro mō ōhoku uri whakaheke i tēnei wā – koina te take i āia ahau te whai i kā tikaka o rātau mā, kia ora tou ai aku uri o te ake ake.

Ōpihi River

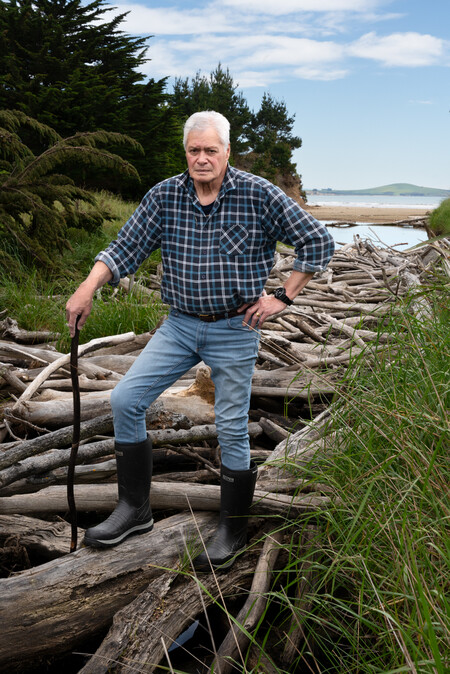

John Henry (Kāi Tahu, Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua)

Takata Kaitiaki Chair / Toihau Takata Kaitiaki, Cultural Consultant / Mātaka Tikaka, Plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Mel Henry (Kāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe)

Te Rūnanga o Moeraki, Te Rūnanga o Waihao.

Anne Noble For a Greenworld centre-pivot Irrigation system, Ōpihi catchment 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

The rivers in our region – the Ōpihi, the Temuka, the Ōrāri and the Pureora are all impacted by overallocation of water for irrigation. At the time our regional Zone Implementation Allocation Plan (ZIPA) was being passed two of these rivers were 300% overallocated, and this was allowed by our own regional Water Zone Committee, which developed the zone water allocation plan to stipulate how the allocation of water was to be regulated.

I am a member of this committee, and the Zone Allocation Plan states the process to follow for water allocation. We are supposed to consider environmental needs, cultural concerns and town water supplies before economic concerns – but this just isn’t the case. What should happen is that after environmental needs and cultural concerns have been met, farming and industry can be provided for. But as it turns out, the Zone Committee concentrated on the financial side of things and allocation of water for economic values came first. This is because the time it would take to rectify water quality and water flow issues within the zone is supposedly untenable. This is unacceptable to us. As the representative for Arowhenua on this committee I refused to sign the ZIPA.

There are all sorts of activities within these waterways that are under pressure because the water levels are so low. The breeding grounds of the whitebait are at risk due to water levels no longer reaching the grasses where whitebait lay their eggs. The impact of phormidium and other toxic pollutants often mean our tuna and pātiki cannot be consumed because of the smell and the rotten taste. Even though we have gained a Mataitai reserve on the Ōpihi and Temuka rivers, we are limited in how we can provide mahika kai for our visitors on the marae at times of hui. As a result of this our mana is diminished.

For us, without the wai, there is no life. When the mana has gone from our waterways it goes from our people too. That’s key for us. To give our visitors the proper manaaki, we need those mahika kai species back and healthy. We need to see the flows and the quality of water within our waterways improving so that we can get into our water and get our mahika kai. If the water is safe to drink, then it is safe to swim in and as a result our mahika kai will be safe to gather. This is the only way that we can see our mokopuna getting into the water and getting to know it. I’m loath to think of what may happen in three or four generations. Our people may not hang on to the knowledge that we’ve got about mahika kai and how important it is to our people; the whakapapa of these practices will be lost, and they are being lost.

Anne Noble John Henry (Kāi Tahu, Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua) and Mel Henry (Kāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Te Rūnanga o Moeraki, Te Rūnanga o Waihao), Ōpihi River 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Ko kā awa ki tō mātau takiwā – te Ōpihi, te Temuka, te Ōrāri, me te Pureora ko māuiui i te rahika o te whakaratoka wai ki te hāwai. I te wā e whakatauria ana te Mahere Wāhi Whakatūtaka Whakarato ā-Rohe (ZIPA) e rua kē o ēnei awa ko rahi ake te whakaratoka hāwai i te 300 ōrau, ā, i whakaaetia e tō mātau ake Komiti Wāhi Wai, nā rātau te mahere whakaratoka wai i tohutohu atu te whakariteka ā-ture o te whakaratoka o te wai.

He kanohi au ki tēnei kōmiti, ā, ka taukīhia te Mahere Whakaratoka Wāhi ko te tukaka ka whāia kia tika te whakarato i te wai. Te tikaka ia ka āta whakaarohia kā matea o te taiao, kā māharahara o te tikaka, me te hopua wai māori o te tāone, i mua i tā mātau titiro atu ki kā hua ki te ōhaka – ekari, hē rawa atu tērā. Te tikaka ia, ā muri i te whakatauka o kā matea taiao me kā māharahara tikaka, ka whakaratohia te wai ki kā pāmu, ki te ahumahi anō hoki. Ekari, kīhai i pērā, i aro

pū atu kē te Kōmiti Wāhi ki kā māharahara ōhaka, ā, mātua tā rātau whakatau i te whakaratoka wai e hākai kē ana ki kā uara ōhaka. Ko tā te kōrero ka pērā te roa o te wā ki te whakaora i te wai, ki te titiro ki kā take mō te rereka o te wai anō hoki

i roto i te wāhi nei e kore rāia ēnei take e tautinei. Hē rawa atu tēnei ki a mātau. Kīhai au i whakaae, hai kanohi o Arowhenua ki te kōmiti rā, ki te waitohu i te ZIPA.

He nui tou, he kanorau tou kā momo mahi ki ruka i ēnei arawai e kore e taea te mahi tika i te mea he tino pāpaku te wai. Ko tūraru kā wāhi whakatipu o te īnaka i te mea kāore tou te kārewa o te wai e tae atu ai ki kā pātītī i reira whānau atu ai ā rātau hua. Mā te pāka kino atu o te huakita phormidium me ētahi atu matū tāoke e kore e taea e mātau te tuna, te pātiki rānei te kai i te mea he hauka, he pīrau hoki te tāwara. Ahakoa ko whakaaehia tō mātau Mātaitai ki te Ōpihi me te Temuka, ko herea tou te momo mahika kai ka taea te hora ki mua i ā mātau manuhiri ki kā hui kai te marae. Nā konei, mimiti ai tō mātau mana.

Ki a mātau, ina he wai kore, he oraka kore. Ki te karo te mana i ō mātau arawai, ka karo hoki te mana o te takata. Mātua nei tēnei āhuataka ki a mātau. Kia manaakitia tikahia ai ā mātau manuhiri, kai te hiahia kia hoki mai, kia hoki ora mai kā momo mahika kai katoa. Me kite anō mātau te rere me te horomata o te wai i roto i ō mātau arawai e piki ake ana kia taea ai anō mātau te kau atu ki te wai ki te kohi i ā mātau mahika kai. Ina he wai pai ki te inu, he wai pai ki te kaukau, ā, ko te hua o tēnā ko te oraka toutaka o te mahika kai. Ko tēnei anake te ara e kitea ana mō aku mokopuna e kuhu atu ai ki te wai, e mōhio atu ai ki te wai. Mauāhara nei au ki te whakaaro ake ki ka whakapaparaka e toru, e whā rānei e heke mai ana. Ka kore pea tō mātau iwi e pupuri ana ki tō mātau mātauraka mō te mahika kai, me te manawapou o tērā mātauraka ki a mātau; ko te whakakapapa o te mahi ka karo, ā, ko te takata hoki, ka karo.

Lake Tatawai

Edward Ellison (Kāi Tahu, Ōtākou)

Upoko o Kāi Te Ruahikihiki ki Ōtākou, Plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble Lake Tatawai 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Out in front of us is a paddock that was once Lake Tatawai – 60 acres of water. We are looking at it from what was once a four-acre reserve issued sometime in the 1880s for the people who lived at the Māori Kāik (Maitapapa) and Ōtākou settlements to be able to access this lake for the seasonal mahika kai activity that sustained them.

In the spring they would have been after moulting ducks and īnaka (whitebait), and tuna in the early summer. There were probably freshwater mussels too, but you’d struggle to find these anywhere now. You’re up to your knees in mud these days, whereas back in the day you could see to the bottom through clear columns of water to gravelly lake and riverbeds. There were flounder as well. Up in the hills you’ve got all the manu (birds) and just down the gorge you have the coast where you’ve got kaimoana. All strong food sources.

So how did Lake Tatawai get to be drained? Well, initially it would have been the farmers down here seeing the potential of beautiful, catchment-rich soil that had been building up for thousands of years or more. Rich, deep, fertile topsoil that grows grass like nothing else. So, yes, it would have been landowners and farmers advocating probably to the Provincial Council and the County Council, as the mindset in those days was to remove every last tree and drain every area that was potentially fertile farmland.

The Taieri Land Drainage Act of 1912 explicitly protected existing ‘native fishing-rights over Lake Tatawai’, but unbeknownst to the people of the Kāik and Ōtākou, lawmaking activities were underway to remove these rights. There was a wee ad in the paper publicly advising stakeholders that things were going to change for them. The Taieri River Improvement Act, introduced in 1920, overrode their fishing rights and when it was passed that same year, it enabled the drainage of Lake Tatawai. But if the people didn’t read the ad in the paper – too bad. They were not able to make a submission or raise their concerns anyway.

Under this act Lake Tatawai and other waters were vested in what was named the Taieri River Trust, which gave rights to divert or drain any river – any body of water in the catchment.

A Trust, they called it. That’s what they would name these entities in those days. Trust implies a bold and virtuous name as if they were giving a virtue to their activities, when in fact, for our people, it was the exact opposite. Through this Act of Parliament, they were being stripped of their rights of access, their traditions, their mahika kai, the ability to practice and pass on mātauraka, and simply just their ability to feed themselves.

When the new law was enacted the drainage of Lake Tatawai went ahead. There was a lot of protest as it took some years to build, construct and do the drainage. But by 1930 all the mahika kai was gone.

Anne Noble Edward Ellison (Kāi Tahu, Ōtākou), Kaiwhare Stream, Ōtākou 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Kai mua rā i a tātau he pātiki, ko te roto o Tatawai tēnei i kā rā o mua – he 60 eka te nui o te wai. Kai te titiro atu ki te roto o mua i tēnei whenua rāhui o mua, e whā eka te rahi i tukuna mai i tētahi wā i te kahuru tau 1880 mō te iwi i te noho ki te Kāik’ Māori (ko Maitapapa), ki kā kāika o Ōtākou hoki, kia whai wāhi ai rātau ki te roto nei, ki tō rātau mahika kai, arā ko te tokoka o tō rātau ora.

I te kana i aru atu ai rātau ki kā pārera maunu, i te tīmataka o te raumati ko te īnaka me te tuna. Kāore e kore he kākahi hoki, ekari he mea uaua rāia te kite i ēnei raki. I ēnei raki tou nei, ka pēnei te teitei o ō turi te hōhonu o te paru, ekari i kā rā o mua, mārama ana te kite i te takere o te roto, he pou wai e piari mai ki te takere kirikiri o te roto, o kā awa anō hoki. He pātiki hoki i taua wā. I kā puke, ko te huhua o kā manu, ā, e tere ana ki te tāwhārua ka tae ki te takutai, i reira te humi o te kaimoana. Kātahi rā te nui whakaharahara o te kai o konei.

I pēhea i whakatahe ai a Tatawai? Tuatahi ake, ko kitea e kā kaiahuwhenua te pitomata o tēnei whenua haumako, o tēnei whenua kenepuru ko hua mai i kā mano tau i mua. He māpua kura, he onemata hōhonu, e tipu matomato ake nei te pātītī. Heoi anō, āe, ko kā kaipupuri whenua Pākehā, ko kā kaiahuwhenua Pākehā te huka i te tūwhana atu ai ki te Kaunihera Porowini, ki te Kaunihera ā-Rohe hoki, ko te

motuhaka atu o te taka o te roi o kā rākau katoa te aruka o taua wā, ka whakatahehia kā wāhi katoa kia huri te whenua hai pāmu haumako.

Mārama pū te tiaki i kā ‘mōtika hī ika Māori ki te roto o Tatawai’ o te Ture Whakatahe Whenua ki Taieri 1912, ekari, he kōrero ki ruka, he rahurahu ki raro, kāore te iwi o te Kāik’, o Ōtākou rānei i te mōhio i te whai ara te ture ki te tīnei i ō rātau mōtika. I kawea e te niupepa tētahi whakatairaka paku e whakatītina atu ana te huka whaipāka ki kā panonihaka i mua i a rātau. Hai te tau 1920 i puta mai he kōrero mō te Ture Whakapaipai i te Awa o Taieri, ā, mā tēnei ture ō rātau mōtika hī ika e poko, ā, i tāhana whakatokaka i tērā tau, i taea e rātau te katoa o te roto o Tatawai te whakatahe. Ki te kore te iwi i pānui i te whakatairaka ki te niu pepa, auare ake. Kāore i whai wāhi rātau ki te tuku tāpaetaka, ki te tohe rānei mō ō rātau māharahara.

Ki raro i tēnei ture, ko Tatawai, ko ētahi atu wai hoki ko noho ki raro i te Tarahiti o te Awa o Taieri, nā, ko tukuna ki a rātau te mana papare awa, te mana whakatahe awa, ahakoa te awa – ahakoa te momo wai, i te riu hopuwai o Taiari.

Ki tā te Māori, ko te Trust te whakapono. Koia tā rātau whakaikoa o aua rakatōpū i aua rā. Kai te kupu ‘trust’ kā uara pākaha, kā uara kākaupai, anō nei he tika ā rātau mahi, ekari rā ia, ki tō mātau iwi, ko te tauaro kē o aua kupu te otika. Nā taua Ture Kāwana, ō rātau mōtika ahikā i poko, ō rātau mōtika whai wāhi ki ō rātau whenua, ā rātau whakariteka, ō rātau mahika kai, te āheika o te iwi nei ki te mahi i ā rātau mahika kai, ki te tuku iho i ō rātau mātauraka, ā, ki te whākai noa rātau ki a rātau, katoa katoa aua āhuataka, i poko.

I te wā i mana ai taua ture, i whakatahea a Tatawai. Mautohe nui ana i te mea he roa tou te wā ki te waihaka i te tūāhaka whakatahe. Ekari, kia tae atu ki te tau 1930, ko karo katoa taua mahika kai.

The Māori Kāik

Edward Ellison (Kāi Tahu, Ōtākou)

Upoko o Kāi Te Ruahikihiki ki Ōtākou, Plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble Māori Kaik Road 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

We are looking at what used to be the Māori Kāik (Maitapapa), which is the name of the village that stretched right along this flat area of land alongside Māori Kāik Road and the Taieri River not far from the huge expanses of the Waihola and Waipōuri wetlands.

Before the First World War, when my dad was a young boy, he would come and stay here with his uncle and aunty, Henry and Rīpeka (Karetai) Mātene for the tuna season, the waterfowl season and other gathering seasons. He was probably only of school age and gathering from his kōrero, he would go with his uncle from the Kāik and fish on Lake Tatawai, which was a very important place for the people living here. The Kāik was close to important mahika kai resources that supported the community and Ōtākou whānau undertaking seasonal mahika kai activity.

Over time the people lost access to parts of the wetlands through privatisation and fencing of the land. People objected to the local takata whenua traversing their lands, so they were slowly hemmed into an allocated fishing reserve at Lake Tatawai.

What happened then was that our legal rights of access to Lake Tatawai were removed by an act of parliament, and that, of course, is what killed this village. The Māori Kāik was vaporised, because of the loss of Lake Tatawai. This was on top of the wider mahika kai resources that they were losing through land ownership, land sales, increased farming and drainage of the wetlands and lakes. All this happened in the space of one or two generations.

By about 1930 the people had to disperse to survive. Some of them went and lived at Ōtākou or as far north as Tuahiwi – to where they had land and rights. Others just disappeared into the community – shearing, labouring, whatever they needed to do to survive.

This was the ‘assimilation policy’ being lived out. Assimilate the people! Let them leave their ways, beliefs, and values! Join the wider community! Be part of the good workforce! And that is what happened. Large numbers of those families who had to leave the Kāik had to merge into the wider community, and in some cases were lost to their hapū and their iwi. Many villages like the Māori Kāik disappeared off the map.

By the time the Waitangi Tribunal came around in 1987, there was still a generation who knew these times. But from that time to this, the bulk of our time is spent doing resource consents, and putting into place policies plans to reverse the loss – to restore the health of our waterways and influence the councils and the powers that be that the continued devaluation of water is not sustainable in the long term.

The health and wellbeing of our waterway ecosystems, of our rivers and lakes, and the cultural values and traditions necessary for community well-being should come first. People’s need for healthy drinking water is a priority too. But economic uses of water should not be prioritised above the health and well-being of our waterways and the people who live nearby, who value and use them.

Kai te titiro ki te Kāik’ Māori o mua (ko Maitapapa), koia te ikoa o te kāika i toro atu ai i te roaka o tēnei wāhi papatahi o te whenua kai kā tahataha o te Rori Kāik’ Māori me te awa o Taiari, ehara i te tawhiti i kā wai tahora nui o kā repo o Waihora, o Waipōuri anō hoki.

I mua i te Pakaka Nui Tuatahi o te Ao, nō taku hākoro e tama noa ana, ka haere mai ia ki konei ki te noho ki te taha o tōhona hākoro kēkē me tōhona hākui kēkē, Henry rāua ko Rīpeka (Karetai) Mātene ki te mahi tuna, ki te mahi manu, ā, ki te mahi i ērā atu kai anō hoki. He tamaiti kura pea ia i taua wā, nā te āhua o tana kōrero, ka haere ia ki te taha o tōhona hākoro nō te Kāik’ ki te hī ika ki Tatawai, he wāhi whakahirahira nui ki te iwi i te noho ki konei. I te noho tata te Kāik’ nei ki tētahi mahika kai whai huanui i hīia, i haoa e te hapori, e kā whānau o Ōtākou i a rātou e kohi kai ana, e mahi kai ana i kā wā tika o te tau.

Haere nei te wā, i haukoti te wāhi ki te iwi ki te haere ki ētahi wāhi kai te repo, nā te whakatūmataiti, te whakataiapa hoki o te whenua. I te whakahē kā kaipupuri whenua Pākehā ki te takata whenua e takatakahi ana i ō rātau ake whenua, heoi anō, haupunu ana te takata whenua ki tētahi whenua rāhui ki Tatawai.

A muri atu i tēnā, i haukoti ō mātau mōtika toro atu ki Tatawai i tētahi ture kāwana, ā, nā whai anō, mā reira mate ai te kāika. I whakatākohuhia te Kāik’ Māori i te whakataheka o Tatawai. He mea heipū tēnei ki te haukotitaka o tā rātau āhei ki kā mahika kai o te takiwā i te kapoka ake o te Pākehā ki te whenua, te hokoka atu o te whenua, te whakapikika ake o te mahi ahuwhenua, ā, o te whakataheka o kā repo me kā roto hoki. I roto i te rua whakapaparaka pahawa ai ēnei mahi.

Tae noa ki te tau 1930 i marara atu te iwi, kia ora ai rātau. Ko ētahi i nuku atu ki Ōtākou, ko ētahi i nuku atu ki te raki ki Tuahiwi – ki tētahi wāhi he whenua, he mana kē ō rātau. Ko ētahi atu i hono noa, i karo noa ki te hapori whānui – i kuti hīpi, i mahi noa, i aro atu ki tētahi mahi e ora tou ai rātau.

Ko te whakatinanataka o te ‘kaupapa here whakawhenumi’ o te kāwana. Whakawhenumihia te iwi! Māwehea ō rātau tikaka, tō rātau Māoritaka, ō rātau uara! Me noho noa hai kiritaki o te hapori! Me whai wāhi ki te ohu mahi pai! Koina te hākai. Tokomaha tou o aua whānau i wehe atu i te Kāik’ i whenumi atu ki te hapori whānui, ā, ki ētahi o ērā whānau i karo atu ai i ō rātau hapū, i ō rātau iwi. He maha hoki o kā kāika, pēnei i te Kāik’ Māori nei i nunumi atu i te mahere whenua.

Tae noa ki te taeka mai o te Taraipiunara o Waitangi i te tau 1987, i reira tou tētahi reaka i te mahara tou ki aua wā. Ā mohoa noa nei, ka pau nei te nuika o tō mātau wā ki te mahi i kā whakaaetaka rawa taiao, ā, e whakatūria hokitia he kaupapa here, he mahere hoki ki te whakaora anō ai aua mea ko karo – ki te whakaora anō aua arawai, ki te ākī atu ai ki kā kaunihera, ā, ki kā mana whakahaere o kā tāone ehara te whakaparahakotaka toutaka o te wai i te tohu o te ora mauroa.

Mātua te whai i te hauora, i te oraka o kā rauwirika kaiao wai, o ō mātau awa, ō mātau roto, kā uara me kā tikaka Māori e tika ana kia ora ai te hapori. Mātua anō hoki te wai māori he wai ora i te takata. Ekari kia kaua e tū matua kā whakamahika ohaka o te wai ki ruka ake i te hauora me te oraka o kā arawai, o te iwi hoki e noho tata ana, e kaikākau ana, ā, e whakamahia ana hoki aua wai.

Wai Wherowhero Stream

David Higgins

Upoko o Te Rūnanga o Moeraki. Plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble Wai Wherowhero Stream, Moeraki 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Wai Wherowhero is an ancestral name that has been etched in our landscape for generations. It’s one of those old names that is important to our history and to the traditions of Āraiteuru and Te Wai Te Ruati.

The Wai Wherowhero stream has been a source of mahika kai for generations. When I was a young teenager, I remember coming to gather the tuna and birds which were plentiful and readily available here.

The Wai Wherowhero is a creek. It is not a big river. It was a really special place because it supplied plentiful mahika kai resources and was easily accessible from the pā at Moeraki. It was within an hour’s walk along the beach towards Te Kaihīnaki – (the Moeraki Boulders) – a place where we could gather our mahika kai without having to travel too far.

Mahika kai is not just kai. It’s not just food. We understand mahika kai to mean all the resources we require to sustain life and all those materials we need for a range of cultural practices. It includes all living things in and near a waterway as well as the water itself.

Our tohuka used to walk up the Wai Wherowhero valley and into the bush to gather some of the medicinal plants we required. My great-grandmother and my grandmother used to gather the dark ink-coloured natural muka dye they used for the dyeing of piupiu and their other weaving work. Now there’s no access for these resources anymore.

Where I am standing by the stream, Wai Wherowhero is now blocked from being able to flow properly. I remember this creek flowing quite readily and being naturally flushed by the tides twice a day. So, I am saddened to see this change as the water is not flowing as it would have done in generations past.

What we have now is a blocked waterway that is polluted as well. The water is basically stagnant. Most of the material that you see in the creek has probably come from forestry slash that has been washed up on the beach and then pushed up into the creek by the tides. The slash, the pollution levels, the low flows and high toxicity at the mouth are all the result of farming and forestry practices happening upstream in the catchment. It’s not all dairying. It’s forestry and farming combined. It’s a mix of causes.

The Wai Wherowhero is just one of many slow flowing creeks all along Te Tai o Araiteuru that are struggling in the same way. The Kurīti and the Kurīnui, the twin creeks north of Te Kaihīnaki. These little creeks are important places and the impacts on their health are a sad reflection on the state of our environment. And the saddest thing is – this has all happened in my lifetime.

Anne Noble David Higgins (Upoko o Te Rūnanga o Moeraki), Wai Wherowhero Stream, Moeraki 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

He ikoa tipuna a Wai Wherowhero, he ikoa nō whakapara ko kawea e te whenua. Koia rā tētahi o aua ikoa whakahirahira nō tāuki, nō kā tāhuhu kōrero o Āraiteuru, ā, o Te Wai Te Ruati.

Nō kā whakatipuraka e hia nei ki mua noho ai te Wai Wherowhero hai wāhi mahika kai. Nōku e taitama ana, mahara ana taku haere ki te hao i te ranea o kā tuna, ki te kohi i te huhua o kā manu, me te māmā hoki o taua mahi.

He awaawa te Wai Wherowhero, ehara i te awa nui. He wāhi motuhake i te humi o kā mahika kai ki reira, te kāwari hoki o te toroka atu mai i te pā i Moeraki.

Poto iho i te kotahi hāora anake te roa o te hīkoi ki tātahi, ki Te Kaihīnaki, he wāhi e tata mai nei i mahi kai ai mātau.

Ehara i te mea ko te mahika kai, he take kai anake. Ki a mātau, ko te mahika kai, he mahika rawa, ka kohia kā mea katoa e ora tou ai te takata, kā mea katoa e hiahia ana kia ea ai kā momo tikaka katoa. Tae noa atu ki kā koiora katoa kai roto, kai kā tahataha hoki o te arawai, tae noa atu ki te wai tou.

I te hīkoi tō mātau tohuka ki te riu o Wai Wherowhero ki te kahere, ki te kohi i kā tipuraka rokoā e hiahiatia ana. I te kohi taku tipuna taua rāua ko taku taua ake i te waikano uriuri hai tāwai i te muka, hai tāwai i te piupiu me ērā atu o ā rāua mahi raraka. Ko aukati te ara ki aua rawa ināianei.

Te wāhi e tū nei au ki te taha o te awaawa ki te Wai Wherowhero ko purua kētia tōhona rereka tika. Mahara nei au te rere pai o te awaawa nei, ā, i totōhia noatia e kā tai, kia rua kā wā ia te raki. Pōuri ana au ki te kite i te wai e whakaroau nei, e kore tou e rere tika ana pērā i te wā o ōhoku tīpuna i mua.

Ināianei, he arawai ko puru, ā, he paru anō hoki. He wai whakaroau. Ko te kōkīkī ka kitea ki te awaawa nei, ko rere mai pea i te para ahukahere ko pae mai i te tai, ā, ko kawea ki te awaawa e te tai pari. Te kōkīkī, te paruparu o te wai, te pāpaku o te rereka wai, te kaha paitini kai te wahapū, katoa katoa he hua nā te mahi ahuwhenua, te mahi ahukahere kai te hikuwai, kai te riu hopuwai anō hoki. Ehara i te mea, nā te ahumīraka anake. Nā te ahukahere, nā te ahuwhenua anō hoki. He whenumitaka o kā pūtake o te mate.

Ko te Wai Wherowhero tētahi anake o kā awaawa rere pōturi e maha kai te roaka o Te Tai o Āraiteuru e pēnei ana te putaka mai o te raruraru. Te Kurīiti me te Kurīnui, he awaawa mahaka kai te raki o Te Kaihīnaki. He wāhi whakahirahira ēnei awaawa iti nei, ko kā pāka kino ki ēnei awaawa he tohu pōuri o te tūāhua tou o te taiao. Ko te mea matapōrehu – i taku oraka tōu tēnei i pahawa nei.

Pureora and Waiho Rivers

Tewera King

Upoko, Te Rūnanga o Waihao, Upoko, Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua, Plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble Waihao River, Toxic Algal bloom 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

It was 1993 when my wife and son first started coming down here. That’s when we would notice how the rivers would dry up around the months of January and February – especially the Waihao. Once the autumn came and the rains started again, the river would start flowing again. What is happening now is that the time between the drying of the rivers and the return of the flows is getting longer and longer. Now it sometimes dries up in November and even in parts of the winter there’s no water flowing through until the next big rain dump.

It is irrigation and dairying that are the causes of this change. If you look back at what they would traditionally be farming down here, it wouldn’t be dairying. Back in the days when my father-in-law and his family were working on the land, it was crops, potatoes and sheep. The environment would dry up during the summer and that was really conducive to crops and sheep farming.

But when banks own your mortgages they’ll tell you what you can and can’t bloody farm. Some of the farmers here have changed to dairying intentionally because that’s what they needed to do to survive, but there are other farmers that I know who didn’t want to go that way. They wanted to stay with crops and with sheep. I know one family that still does. The others, whether by choice or not, have moved into dairy farming with the need to irrigate and all else that goes with it.

I am standing in the Pureora river in the Taiko catchment. Here the nitrate levels and other toxin levels in the ground and in the water have reached pretty bad levels. You can see the water is paru, both in the Pureora and in the Waihao, and it will get worse and worse as the days go on. There is algae and the black cyano-bacteria is just beginning to settle on the rocks. In a month or even less than that, it’ll start to join hands, sing Kumbaya and what you’ll see is that black stuff from bank to bank. Then the signs go up that say you can’t let your dog go swimming. Would you want to risk getting out of there to catch and eat something from that water? Whatever might affect the dogs is probably being consumed by whatever kai you’re trying to collect from the river as well.

Every time this happens we have to have a closed season, which affects our mahinga kai practices. This is our tikanga and the loss of guaranteed access to our food and our food sources breaks our contract with the Crown in terms of Te Tiriti. That affects our mana and our own mahinga kai practices are dying out because of it. We need safe access to our mahinga kai sites restored and to be able to practise our mahinga kai so our kids don’t lose it.

Anne Noble Tewera King (Upoko Te Rūnanga o Waihao, Upoko Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua), Pureora River 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

I tīmata mātau ko taku wahine, ko taku tama te haere mai ki konei i te tau 1993. Koina te wā e kitea e mātau ka maroke ngā awa i ngā marama o te Iwa me te Ngahuru – inarā te Waihao. Ka ngahuru rāia te tau, ka heke anō mai te ua, ka rere anō te awa. Ināianei, ko te wā i waenga i te whakamaroketanga mai o te wai, ki te rerenga anō o te awa e roa haere ana, e roa haere ana. I ētahi wā ka maroke i te Whitu, ā, tae rā anō ki te makariri, kāore anō te wai kia rere, kia kaha anō mai te heketanga o te ua.

Ko te mate ia, ko te hāwaiwai, ā, ko ngā pāmu ahumīraka. Ki te titiro whakamuri ki ngā momo pāmu i te wā o mua, ehara i te mea he pāmu ahumiraka. I ngā rā o mua, i te wā e mahia ana e tōhoku hungarei me tōhona whānau ki te whenua, he otaota kē, he rīwai, he hīpi. Ka maroke te whenua i te Raumati, ā, he mahi whai hua tērā ki ngā otaota, ā, ki ngā pāmu ahuhīpi anō hoki.

Engari, ina nā te whare pūtea kē tō mōkete, mā rātau kē koe e whakahau mehemea e taea ana te mahi ahuwhenua, e kore e pūrari taea rānei. I āta whakawhiti atu ētahi kaipāmu ki te ahumīraka kia ora ai rātau, engari arā ētahi atu e mōhio nei au, kāore i te hiahia kia whakawhiti. I te pīrangi ki te noho tou ki te ahuotaota, ki te ahuhipi anō hoki. Kai te mōhio au i tētahi whānau i ū tou, i mau tou. Ko ērā atu, ahakoa nā rātau rānei te whakatau, e kore rānei, ko whakawhiti atu ki te ahumīraka, me te hiahia hāwaiwai, me ērā atu āhuatanga o taua momo mahi ahuwhenua.

Kai te tū au ki te Pureora ki te riu hikuwai o Taiko. Ki tēnei wāhi ko piki kino mai te maha o ngā pūkawa ota me ērā atu tāoke ki te whenua, ā, ki roto i te wai anō hoki. Kai te kite te paru ki roto i ngā awa e rua, te Pureora me te Waihao, ā, haere nei te wā ka kino haere, ā, ka kino rawa atu. He pūkohu wai, ko te huakita

pango ka tatū mai ki runga i ngā kōhatu. Hai tētahi marama, poto iho rānei i tēnā, ka piripiri ngā ringaringa, ka waiatahia a Kumbaya, ā, ko tā tātau e kite nei, ko ēnei mea pango e toro atu mai tēnei parenga, ki tērā. Kātahi, ka whakatūria ngā tohutohu kia kaua koe e tuku tō kurī ki te kaukau. Ka puta tūpono atu ai koe ki te hī kai, ki te hao kai i taua wai? Ko taua mea e pā kino atu ai ki tō kurī, ka kainga hoki e te kai e ngana hoki ana koe ki te kohi.

Hai ia wā ka puta mai tēnei āhuatanga, ka aukati te tau kai, ā, ka pā kino hoki ki ā mātau mahinga kai. Ko tā mātau tikanga tēnei, ko te motunga o ā mātau herenga aukaha ki ā mātau mahinga kai, ki te takenga mai o ā mātau kai hoki i kī taurangi ai e kore rāia e māwehe, e takahi ana i ngā whakataunga o te kirimana ki te Karauna, ki ngā whakataunga hoki o Te Tiriti. Me whakahou anō tā mātau hokinga haumaru atu ki ō mātau mahinga kai, kia taea ai e mātau ā mātau mahinga kai e tutuki, kia kore ai e ngaro i a mātau tamariki.

Kōreti New River Estuary

Michael Skerrett (Kāi Tahu, Waihōpai)

Upoko o Te Rūnanga o Waihōpai, Plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble Waihōpai River, Invercargill is one of the many contaminated waterways that feed into Kōreti New River Estuary 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

It’s in the estuaries where you really see the cumulative effects of increasing sedimentation levels and the toxicity of our waterways. Take the Ōreti River, for example. There is the Lumsden sewage treatment plant adjacent to the Ōreti that discharges into it. The Winton Sewage Scheme discharges via a creek into the Ōreti River. Further down river the Makarewa freezing works discharge into the Makarewa River which then goes into the Ōreti. The Alliance Freezing Works also discharges into the Makarewa and then you’ve got all the discharges from Invercargill City itself.

While each consent granted for use of a waterway may only have minor effects, the RMA doesn’t really deal with how these effects accumulate. This means we have huge pressure on our waterways. The excess of nutrients from all these different sources creates the nuisance growth that makes more and more areas of the estuary anoxic and is so detrimental to our mahinga kai.

I think in New Zealand we’ve got probably some of the best farmers in the world and they’re keen to do the right thing. I’m not blaming them at all, but I think longer term, we need different methods of dealing with sewerage and effluent rather than treating it and discharging it into our waterways and we must change how we are farming. We can’t keep pouring nutrients and herbicides on to the land and into our waterways.

We should be looking seriously at regenerative farming methods and how we can get a premium for our products by valuing the biodiversity that is so important to the life of the soil and the life of the planet. I believe things can be turned around, but not by pouring millions of dollars into trying to fix the problems through such things as nutrient budgeting and setting nutrient limits. This way just won’t work.

If we look after the whenua and the wai, they will look after us. This was a lesson that Māori learned within the first couple of hundred years that they were here. They had to adapt to the seasons, because they had come from a different world altogether where there were crops all year round. They made mistakes, but they learned from them and our resource management and conservation strategies evolved from experience developed over the first two hundred or so years that Māori were here. Now the greater population is having to go through the same thing again. But it is hard to have all that we have already learned not listened to or understood.

Anne Noble Michael Skerrett (Kāi Tahu, Waihōpai) and Dr Jane Kitson (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Mamoe, Waitaha), Kōreti New River Estuary 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Kai ngā wahapū ka tino kite i ngā pānga tāpeke o te pikinga o te parakiwai me te tāoke o ō mātau arawai. Tirohia te Ōreti, hai tauira. Kai reira te taupuni whakatika parakaingaki kai Lumsden kai te tahawai o te Ōreti, ā, ka tukuna tana para ki te awa, te Kaupapa Parakaingaki kai Winton, ka tukuna ā rātau para ki tētahi awaawa ki te Ōreti. Haere whakararo tou ki te whare patu mīti ki Makarewa, ka tukuna ā rātau para ki te awa o Makarewa, kātahi ko ngā tukunga para katoa nō te tāone tou o Murihiku.

Ahakoa pea e hauwarea noa te pānga o ia whakaaetanga ko whakatauria mō te whakamahinga pēnei nei o te arawai, kāore i te aro atu ki te tapeketanga o aua pānga. Mā reira he taumaha ngā paru e kawea ana e ō mātau arawai. He nui rāia ngā taiora i ēnei wāhi katoa ka matomato te tipu o te pūkohu wai, ā, ka piki ake, ka piki ake ngā wāhi hāora kore o te wahapū, ā, he mea whakawara i ō mātau mahinga kai.

Ki a au nei, kai a Aotearoa ētahi o ngā kaiahuwhenua pai rawa atu o te ao, ā, hīkaka ana rātau kia tika ai ā rātau mahi. Ehara au i te whakatakoto te hē ki mua i rātau, engari, ki te whakaaro mō te pae tawhiti, e matea ana tātau ki ētahi atu tikanga, ki ētahi atu tukanga ki te whakatika i te parakaingaki me te parapara, atu i te whakamahine noa, kātahi ka tukuna atu ki ō tātau arawai, ā, me rapu hoki i ētahi mahinga ahuwhenua hou. E kore tou e taea te riringi atu i te taiora me ngā patu otaota ki te whenua, ā, ki roto hoki ki ngā arawai.

Me āta titiro, me titiro kau ki ngā tikanga pāmu torokiki, ngā tikanga toitū o te mahinga whenua, ā, ka nui hoki te utu ka whakawhiwhia ki ā mātau haumāuiui i te whakarangatira i te rerenga rauropi, tētahi āhuatanga mātuatua o te oranga o te oneone, me te oranga o te ao. E whakapono ana au ka taea te tahuri atu i te ara e haere nei tātau, engari ehara mā te whiuwhiu i te manomano tāra ki te whakatika i ngā raruraru pēnei i te whakatahua taiora, te whakataiapa rānei i te taiora. Ehara mā reira e tika ai te raru.

Ki te titiro ki te whenua me te wai, mā rāua tātau e atawhai. He akoranga tēnei i ākona ai e te Māori i ngā rua rau tau tuatahi o tā rātau noho ki konei. Me urutau ai rātau ki ngā kaupeka hou, i te mea i ahu mai rātau i tētahi ao tino rerekē, i reira tipu ake ai ngā otaota i ngā wā katoa o te tau. I taka rātau ki te hē, engari i ako i aua takanga, ā, ko ā mātau mahi whakahaere rauemi, ā mātau rautaki whāomoomo i kukune mai i aua wheako, i whanake mai i aua rua rau tau koni atu tuatahi o te noho mai nei o te Māori ki konei. Ināianei, he rite tou te takanga me te ako i ngā hapa, engari he tokomaha rāia ngā tāngata. He uaua te kōrero mō aua mea ko ākona kētia ki te taringa tē aro mai, ki te tangata tē mātau mai.

Kōreti New River Estuary

Dr Jane Kitson (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha)

Ecologist / Kaimātai Hauropi.

Anne Noble Toxic leachate from an old landfill at Pleasure Bay, Invercargill. This is one of the many contaminated sites and waterways that feed into Kōreti New River Estuary 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Kōreti is regarded as one of the sickest estuaries in New Zealand, having become the most polluted in the shortest span of time.

The Waihōpai and Ōreti rivers serve as the primary arteries to the estuary. While sediment has always flowed down these rivers, now excessive sediment, coupled with high nutrient levels from intensive agriculture and toxic contaminants from sewage and stormwater, creates the conditions we observe in our estuary.

What we’re looking at is anoxic mud. Beneath that surface, it’s completely black. There’s no life in it; there’s no oxygen, which is the key element for everything that lives, except for anoxic bacteria and the hardiest creatures that can exist without it. This is what we call a gross eutrophic zone – what was once known as a dead zone. It’s paru. This has occurred quite quickly, over just two decades.

Where we’re standing is near Pleasure Bay. It used to be a community area where people would jump in the water and gather kai. The estuary was a food basket full of life and vitality, and then the Council put in an open landfill. When you see the glossy oil sheens of the leachates still seeping from the former dump site into the estuary, you don’t want your kids anywhere near it.

Pātiki and tuaki were staple foods for us here. Our kids grew up helping us drag a net for pātiki in the estuary. This is no longer possible because we just get stuck in toxic mud and weed clogs the net. The spots and places where we could easily gather a feed are gone. You can’t even find tuaki anymore. You see dead shells with nothing inside them.

What has also stopped many people from practicing mahika kai is the treated human waste that flows directly into the estuary. Scientists have modelled where the contaminants travel, and although it’s weak, it is still present throughout the entire estuary. Why would you want to put human waste in your food basket? Why would I want to eat someone’s tūtae?

The sad reality for us is that you don’t truly know a place unless you’re immersed in it. You want your children to connect with your land – with your whakapapa, and to care for their environment. To know it. To understand it within themselves and to love it, as it’s a part of who they are. But how can you genuinely love yourself if part of you is so poor, so sick, and so neglected? The whole city has turned its back on the estuary, and what we really need to do is look at it, cherish our connections, and celebrate them while restoring its health and our own.

Ko Kōreti tētahi o kā wahapū māuiui rāia ki Aotearoa, i te mea koia te wāhi parahaka tino kino i te wā poto rawa atu.

Ko kā awa o Waihōpai, o Ōreti ko kā awa matua ka rere atu rā ki te wahapū nei. Ahakoa nō tāuki tou te rere mai o te parakiwai ki ērā awa, nā te tuhene o te parakiwai o ēnei raki, tāpirihia ki te maha hoki o te taiora mai i te ahuwhenua kakati me kā tāhawahawa tāoke mai i te paratakata me te waiua ka puta mai te āhua e kitea ana ki tō mātau wahapū.