The Edge of the Sea

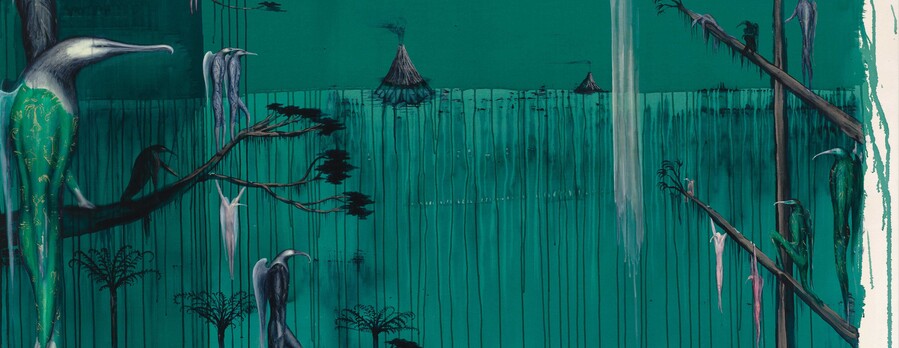

Bill Hammond The Fall of Icarus (after Bruegel) (detail) 1995. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1996

A vision of New Zealand’s past from 1995:

Europeans first imagined New Zealand as “a garden and a pasture in which the best elements of British society might grow into an ideal nation”... When the smoke of the colonists’ fires cleared at the end of the 19th century, New Zealand had become a different country. Māori had lost their most precious life-support system. Only in the hilliest places did the forest still come down to the sea. Huge slices of the ancient ecosystem were missing, evicted and extinguished. Our histories, however, have had neither the sense of place nor ecological consciousness to explain what has happened.

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning– William Carlos Williams, ‘Landscape with the Fall of Icarus’

The seer is ecological historian Geoff Park in the introduction to his extraordinary, groundbreaking – and now classic – history of New Zealand’s lowland forests and wetlands that are today destroyed and dense with agrarian diversification, Ngā Ururoa: The Groves of Life. Beginning with James Cook’s Endeavour party on the Hauraki Plains, and then the New Zealand Company’s arrival in the valley that became the Hutt, Park takes us through the river flatlands where the imperatives of colonial settlement transformed the original forests and swamps with ruthless efficiency.

When Park wrote the introduction to his pioneering history he registered one of the first efforts to understand what had happened to our “groves of life”, and what irreparable loss we – tangata whenua and Pākehā – had suffered in the deliberate extermination of nature from New Zealand’s plains.

With some grief and sorrow, but without a tendency to merely lament, Park sought to discover if “anything had survived” and to uncover “the truths, often unpleasant, about ourselves and our attitudes and perceptions that the landscape divulges”. For, as the introduction goes on to say, it is only by “looking intently at a landscape we live in or value to see what it reveals of systems of wisdom and warning”. 1 That is, to see land as community to which we belong, rather than a commodity we trade or a resource we exploit.

From 1989 artist Bill Hammond had begun to give these issues appropriate and unforgettable visual form. In that year he stayed for a month with a small group of other artists and photographers on the Subantarctic Auckland Islands.

Hammond it seems was profoundly moved by the sight of hundreds of large seabirds lined up on the rocky foreshore, staring out to sea. This scene of innumerable birds silently watching, and being observed in their turn by the artist, became a rich source of thematic material for Hammond’s subsequent paintings. The painted birds were clothed and anthropomorphised suggesting both inbetweeness and metamorphosis across the divide between human and animal.

The air of melancholy and sad omniscience in this “troubled Arcadia” recalled some deep past and ancient memory. In painting after painting Hammond documents the effects of what Allan Smith defines as “the aggressive agricultural program that characterised the first century of European settlement in New Zealand”,2 and the total and deliberate extermination of nature and birdlife from our coastal plains and swamps. In 1995 Hammond’s monumental The Fall of Icarus (after Bruegel) is a defining visual statement of Park’s critique of colonial destruction by early settlers who felled, burned and milled vast tracts of coastal and inland forests, and deliberately or inadvertently destroyed countless (bird) species, to make way for the agricultural hinterland that served Great Britain from its outpost of Empire. We still have to learn how not to allow what Park calls the “campaign against nature” to stand for our human condition.3 We have to detach ourselves from its myth of progress and, like Hammond, personalise our imaginative reckoning with the morally-compromised past. To quote Park’s introduction again and his own account of the undertaking: “Reading the landscape is like collage, interweaving the patterns of ecology and the fragments of history with footprints of the personal journey.”

Bill Hammond The Fall of Icarus (after Bruegel) (detail) 1995. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1996

Hammond’s The Fall of Icarus aims to put an intimate knowledge of landscape from the inside behind it. And it does so by going back and reflecting on the past of painting, in particular to Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c. 1558).4 Interestingly, in referencing Bruegel, Hammond choses as his source a painting that has an even more distant classical starting-point. The best-known version comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, probably the source that Bruegel himself knew, given that the text (and variations thereof, such as the late-medieval Ovide moralisé (1484)) circulated widely at the time.5 In Book 8, lines 183–259, Ovid recounts how Daedalus, imprisoned at Crete while constructing the labyrinth for King Minos, employed his cunning to escape by fashioning wings for himself and his son Icarus out of feathers and wax. Daedalus warned Icarus to keep to the middle way when flying, avoiding both sun and water, but after initial obedience the boy soared too high, whereupon the sun’s heat melted the wax, plummeting him down into the sea.6 Bruegel clearly demonstrates his familiarity with Ovid who mentions a ploughman, a shepherd, and a fisherman who each stopped his respective activity and was mesmerised by the sight of those airborne above.

But Bruegel’s treatment of these menial characters in regard to Icarus is radically different from that of his source. In the painting, instead of being mesmerised by a human falling from the sky, Bruegel shows them oblivious to the drama around them. Even the figures busily scaling the rigging of the ship at lower right notice neither Icarus nor the feathers floating past the sails. Indifference and preoccupation are everywhere. Daedalus, moreover, makes no appearance in the scene unless one understands that the painting’s elevated viewpoint implies that Bruegel’s scene of Icarus’s fall is seen from Daedalus’s still aerial point of view.7

Two poems, which Hammond knew, have also been particularly influential in modern perceptions of Bruegel’s painting.8 W. H. Auden’s ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’ of 1938 has reinforced the interpretation of the painting that has dominated twentieth-century art historical writing:

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.9

Detachment in the face of human suffering is everywhere and, as the reduction of the traditional title to the proper name indicates, Auden turns his focus on the drowning figure who Bruegel seems to have downplayed. ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’, it has been argued, represents Auden’s impending flight from Europe, and from the dead weight of Europe’s history and politics which was becoming unbearable, perhaps from premonitions of impending war.10 How, Auden asks, can we take in all that suffering? Is it better to remain detached? Whereas William Carlos Williams puts the landscape back into the title of his 1960 poem – ‘Landscape with the Fall of Icarus’ – and at the centre of his interpretation.

The indifference that greets Icarus’s fall is as much a matter of that landscape’s resistance to human concerns as the human limitations implicated by Auden.

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was spring

a farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantry

of the year was

awake tingling

near

the edge of the sea

concerned

with itself

sweating in the sun

that melted

the wings’ wax

unsignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning11

The force of the painting for Williams is thus, I think, to move the viewer not only to recognise the concern for catastrophe inherent in the preoccupation of ongoing life, but also to register a horrified protest that it should be so.

This brings it close to the painful irony of death in the midst of life expressed through the perspective of Hammond’s painting.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder Landscape with the Fall of Icarus c. 1558. Oil on canvas. Musees Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, Belgium

Much has been made, particularly in exhibition labels, of the formal similarities between Bruegel the Elder’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus and Hammond’s The Fall of Icarus: the same elevated viewpoint and high horizon, figures in the foreground, islands in the sea, and the sign of narrativity that is “the tiny body of the fallen Icarus disappearing into the sea”.12 But what if the homage was deliberatively contrastive instead of imitative? European painting is metaphysical or formalistic because it takes the nature of society, the nature of the nation, for granted and works from it. New Zealand painting never seems to get beyond the definition of its starting point; any painting of New Zealand (unless it is a mere imitation of a transplanted European source), New Zealand life, New Zealand content, is a formless one, always to be re-invented, an uncharted wilderness in which the very notion of experience itself is perpetually called into question and revised, in which time is an indeterminate succession from which a few decisive, explosive instants stand out in relief. Hence the explosive interruption of Icarus falling is felt by Hammond as a secret destiny, a kind of nemesis lurking beneath the surface of a hastily assembled and impermanent settler society. The moment of violence is a diversion but one experienced backward in pure thought, as contemplative spectacle.

In European art, people no matter how solitary – like Bruegel’s ploughman, his shepherd resting on his staff, the fisherman leaning out for his catch and the sailors in their ship’s rigging trimming the sails – are still somehow engaged in the social substance; their very solitude is social; their identity is inextricably entangled with that of all the others by a clear system of class and labour, in what German philosopher Martin Heidegger describes as Mitsein, the-being-together-with-others. But the form of Hammond’s work emphasises the initial separation of his anthropomorphic bird figures from each other, their solipsistic existence, and their need to be linked by some external force, be it the memory of an event in the past, or the premonition of something to come. They are always ‘Bird Alone’ to echo another New Zealand trope. And this separation is projected out into space itself: no matter how crowded the landscape is with birds, the various solitudes never really merge into a collective experience, there is always distance between them. Each fragile perch is separated from the next; each upright figure from the one next to it; each tree limb from the ground beneath or beyond it. That is why the most characteristic leitmotif in Hammond’s painting is the bird-figure standing, looking out of one world, peering absorbed and attentively across into another.

Bipedality – walking, running, standing on two legs – is often incorrectly cited as the prime evolutionary adaptation that distinguishes the human from other animals. Incorrect because, despite the remoteness of their body morphology and their evolution, it is bipedality that yokes together humans and birds. The important recurrent feature of Hammond’s birds is their bipedalism. This theme of bipedalism and standing upright dates from the Auckland Islands encounter but it is there in Hammond’s early work too. It shapes his anthropology. Hammond’s birds rise on two feet and acquire a sense of balance, a feeling for the laws of the physical universe, legs offsetting each other, or kneeling outstretched along a branch, or sitting astride a tree limb. It is their standing upright that encompasses a fantasy of uplifting, of transcendence, and, at the same time, a preoccupation with downfall and ruin. It is difficult to know which comes first in this symbiosis. The verticality of Hammond’s birds becoming-human is the clue to their vulnerability but also their strangeness – their quality of perpetual unfinishedness. Icarus, a human becoming-bird, in contrast is a woosh, an ectoplasmic energy of photons of light.

It is in his treatment of gravity we sense Hammond’s materialism (call this his ‘down to earthness’); his concern for the orientation of the world; the way in which our bodies are connected to the ground; his sense of what makes the body distinctive. It is his version of Allen Curnow’s “trick of standing upright here”.13 For it is anatomical standing which the ground supports but also qualifies. How much of human nature and culture derives from uprightness?

In psychological or allegorical terms Hammond’s figure standing, or balanced on the limb of a tree, represents suspicion. Suspicion is everywhere in this world, peering, barring entry, refusing to answer. Hence the bird figure’s principal contact with the others encountered is a rather external one, they are always seen on their own branches, and their personalities come out against the grain, hesitant, hostile, stubborn. Like dolls dressed up, Hammond’s birds are clothed. And their clothing is a source of endless fascination because it combines with the body in unexpected ways. The tight-fitting smocks in mottled fern patternings, wallpaper designs and willow-pattern china take on a life of their own. Sometimes revealing their wearers, sometimes articulating them, sometimes concealing and muffling them. The birds are not bodies, even when they stand there as human analogues, they are outfits which hide the body. Even so there is a perceived homogeneity of bird people. Like Curnow’s resonant phrase, Hammond’s innumerable watching birds have become idiomatic, like a local patois or slang, a ‘phrase’ that is eminently serial and impersonal in its nature: it exists passed from hand to hand, always elsewhere, never fully the property of its user. In this universalising sense, part of the appeal of Hammond’s work for us is a nostalgic one. Yet the experience of nostalgia remains and itself needs to be explained. Nostalgia is generally characterised by an attachment to a moment of the past wholly different from our own, which offers a more complete kind of relief from the present. The Romantics, for example, reacted against the growth of industrial society by recalling the world of the pastoral. Sections of our own settler society continue to feel this kind of nostalgia for, say, the conditions of the frontier. But, in Hammond’s case, the nostalgia is different and future-driven. It is the result of the desire which Park describes that “aches in all neo-European cultures: the wish that our colonial conquests of the human and natural world finally at an end, we will find our way back to a more equitable set of relationships with all that we have subjugated.”14

Seabirds such as those observed by Hammond are sometimes said to live in colonies. Hammond’s world is fraught with significance, immanent with shadowed meaning, he presents us with a landscape strewn with clues of colonisation and the colonial imperial project. A forest thinned out. An endlessly interpreted world in which practically everything is metaphor and nothing merely itself. Hammond’s paintings at once offer closure, that is an essential self-containedness, but they also, and much more radically, refuse the constraints that closure necessarily imposes. In knowing our history and dealing with the sense of loss they offer the possibility of a redeemed future.

In The Fall of Icarus we observe everything from an unlocated perspective that leaves the purpose of it all in doubt. Hammond is not as much interested in telling a story as making a story happen. There is a desire to communicate and, often, the impossibility of doing so. This is a fact of human existence. How do we cope with it? A traditional painting is a form of representation which involves the creation of an imaginary but ordered space. But what if we lack this sense of epistemological security? What if our experience seems fragmented, partial, incomplete, disordered? Then painting might be a way not of representing but creating order. If painting could be the means of completing, bringing together, enriching the fragments, then it would not be primarily a representation but the search for redemption. It would not be the reproduction or embodiment of some pre-existing knowledge but the satisfaction of the desire to present with appropriate intensity things about which our knowledge is most uncertain.

The Fall of Icarus may make us feel that activity participates in a cosmic process that renders human significance all the more difficult to believe in. One of the most pregnant of the correspondences in the painting is between the large grey and green bird-figures on the left margins of the canvas. The resemblances between the two figures – both facing right, both supporting themselves with an outstretched arm, both with gossamer-like wings – make the differences all the more striking.

They suggest the impulse to rise and aspire – the cause of Icarus’s very downfall. Such patterns begin to appear everywhere as we become attuned to the way the painting ‘thinks’ in terms of oppositions. Yet the tone of the image is not ironic. The proliferation of meaning defies any settled statement. The visual language of The Fall of Icarus is constantly presenting motifs to ponder – the flayed and suspended birdskins for instance – but only in the process of fracturing them into their many aspects and scattering them across the field. Things suspended run the gamut from the deferred to the undecided to the imminent to the gestating to the sublated or uplifted. The rendering of bird bodies, scattered throughout the scene like an arcane alphabet, is only sporadically readable as meaning. The cluster of details is paradigmatic of how meaning suggests itself in The Fall of Icarus.

There is evidence everywhere of dialectical intelligence and of binding things into elaborate structures of intent. For, finally, Hammond is not just a cataloguer but a thinker who exhibits a language of nuance, in which meaning rather than being fixed and encoded both enlists one’s gaze and proliferates before it.

During the 1970s after graduating from art school, Hammond designed and manufactured wooden toys, such as the wooden pull-along alligator with a spiky back and toothy-peg jaws that chomps along the floor. Then he returned to painting fulltime in 1981. In a sense, his painting, too, is less an imitation of reality or the expression of profound truths than it is a kind of toy. The idea of the work of art as a kind of toy may offend but our adult selves hardly need to be reminded of the sacred importance toys had for us in our childhood. And what is a toy? It is something that can be invested by the child’s imagination with properties that are both animate and inanimate. Toys and artefacts are always double: objects and living entities. A painting is marks on a surface and the world those marks evoke.

They can take on a full life and engage our imagination precisely because they do not try to hide the materials from which they are made. Once this doubleness is accepted a new sense of the possibilities of painting emerges. Art is no longer a (poor) imitation of life; it can do things life cannot.

A toy is a complicated object. It is always more than the sum of its parts, but its parts and how they are put together are clearly visible. So too with a Hammond painting.

But as we look at it we discover that it can do things we never dreamed it could. Toys no less than tribal masks, are mysterious and powerful presences. They are mysterious and powerful because of, rather than in spite of, their materiality. There is nothing hidden about their production.

Everything is there for us to see, the paint drips down the canvas. Yet, of course, there is a miracle here: the miracle of the artist’s skill and vision.

Bill Hammond’s paintings have not one form, but two, an objective form and a subjective one, the rigid external structure of a landscape on the one hand, and a more personal distinctive signature, arranged according to obsessive pattern, bird-actors in a psychic drama through which the social world continues to be interpreted. Yet the two kinds of forms do not conflict with each other; on the contrary the second seems to have been generated out of the first by the latter’s own internal contradictions. For the landscape format is also a puzzle in which the faculties of analysis and reasoning are to be exercised. It is, of course, the presence of this kind of probing construction in Hammond’s painting that accounts for his birds’ similarity and repetition as forms.

It is as though an object, bird-people, designed for some purely practical purpose, almost machine-like, suddenly turned out to be of interest on a different level of perception, on the political level for example.

The lost world of Park’s Ngā Ururoa seems close. It is this wider disintegration, I think, that The Fall of Icarus tries to represent. And the idiom that Hammond devised for it – a tragi-comic beauty – could not be more apt. Allan Smith may be right (he is by far the most incisive and sympathetic of Hammond’s commentators) when he says of Hammond’s hybrid forms they create a viewpoint, not necessarily a privileged place to take position in front of the painting, but a virtual standpoint from which the painting’s array of figures will come to make sense and fall into a dramatic relationship with us now:

In their distinctive and uncanny self-containment, they seem to embody ancient wisdom and a sad omniscience. Their beauty has a tragic cast. A delicate and nervous intelligence is quickened through a fearful expectancy. Looking out from a deep past, they perch on the brink of change.15

Nevertheless, Hammond’s The Fall of Icarus is a picture without a single viewpoint. It takes up some of the normal clues and mechanics of perspective (horizon-line, repoussoir framing the edge and guiding the gaze in, and gradated figures in the distance) and then has them disperse and disintegrate (a waterfall of dripping paint and the freefall, semi-transparent ghost of the white air-pocket) as if floating back onto the surface before our very eyes. The double line of the horizon is a signature of this – of perspective’s powerlessness and the inability of those horizons to become, perceptually, any such thing. In this sense one could say that Hammond came to see that the discontinuous, detotalising feel was what his understanding of the history of colonisation demanded. Discontinuity becomes the carrier of the painting’s strange suspension and annihilation of feeling.

In both Hammond’s and Bruegel’s paintings the real challenge – the interest, beyond the fascination of particulars – is to grasp each painter’s tone. In Bruegel what seems to matter most is the sweep and depth of the natural world but, unlike Hammond, it is a world of farming – the ploughman’s foot imperturbably shaping and smoothing each furrow, the sack of seed waiting to be sown – and of trade winds and the commerce of merchant ships: the vita activa. The sun may be what has put an end to Icarus’s attempt at victory over it, but it is now setting in a yellow haze behind the horizon. We understand that the same sunlight that melted Icarus’s wings will remain essential for the ploughman’s bag of seeds to germinate.16 Hammond agrees with very little of this. In his painting the world of work and merchant commerce gives way to an empty timeless realm – a vita contemplativa – where tree branches function as graceless diving boards, or coathangers for flayed skins, or a primitive jungle gym from which to suspend oneself. What Hammond does is paint his subjects in their own world, as they appear in their absence from us, assuming postures calculated to elicit an evocative response. Evocations of emptiness. Aching, yearning, extending out, holding on, pulling back and shrinking in are woven into the kinesis of the scene. Kinetic postures become structuring motifs. Such objectivity is itself moral, though it involves a refusal of all prepackaged moral sentiments. And, as such, it is always on the verge of turning its critique upon itself. For all its apparent detachment, The Fall of Icarus is one of Hammond’s most personal works, fraught with conscience. Bruegel’s soft dazzle of sunlight is replaced by an emerald phthalo-green light and seeping black washes. Icarus’s terrible weightless downward velocity is the scene’s only sign of the active life. He may stand for the ecological disaster of the past; or, in his ‘Christian’ fall a passing evil atoned for and averted? The polarities of pessimism and optimism do not seem to apply; we are somewhere in between with Icarus’s soft splash. The exorcism of the settler past is ongoing.

Hammond’s The Fall of Icarus is a necessary moment in the process of rethinking (demythologising) the silence of history regarding what Geoff Park names as “the ecosystems which the secular world has been so carelessly tearing apart”.17 It admonishes us to save ourselves from the darkness to which Icarus descends. Hammond’s bleak gaiety in the face of catastrophe is the product of a specific reflective moment in our ecological history.

The undertakings of Park’s interrogation seem painfully close. Here are the final words of his introduction to Ngā Ururoa expressed poignantly, and pointedly, in painterly terms: “In other words, the brush should sketch a life, since a life – like the landscape – is constituted by the traces left behind and imprints silently borne.”