Power Play

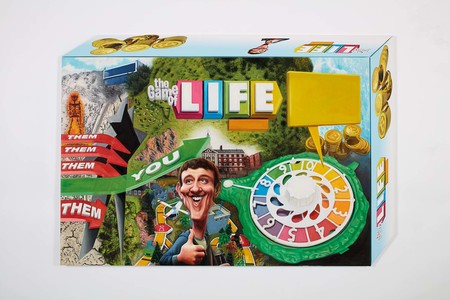

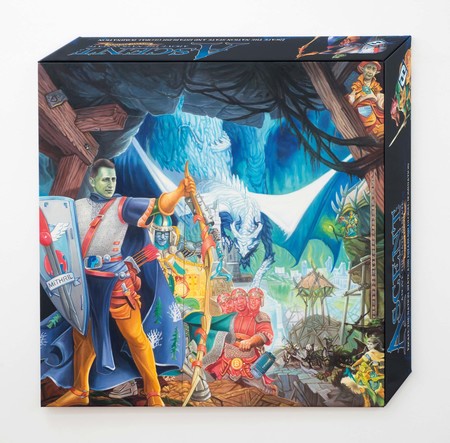

Simon Denny Above the Nation State Board Game Display Prototype (detail) 2017. Mixed media. Private collection, USA

In November 2017, Simon Denny’s The Founder’s Paradox opened at Michael Lett Gallery in Auckland, the first solo exhibition Denny had made specifically for New Zealand audiences in several years. His starting point for the project was local: the news, broken by New Zealand Herald journalist Matt Nippert in early 2017, that the billionaire tech investor and Donald Trump supporter Peter Thiel was in fact a New Zealand citizen.

Simon Denny Canvas Work Game of Life Cover 2017. Commissioned painting, UV print on canvas. Private collection, Auckland

The story was perfect for Denny, an artist whose work has regularly looked at the intersections between new technologies, geopolitics and New Zealand. In 2012, he made Channel Document (which won the prestigious Baloise Prize at Art Basel). The following year, he made his immense installation The Personal Effects of Kim Dotcom, first in Vienna and later at Wellington’s Adam Art Gallery. Then there was his hugely successful presentation at the 2015 Venice Biennale, Secret Power, which simultaneously looked at the graphic design culture of America’s National Security Agency and New Zealand’s place within the Five Eyes intelligence alliance.

Peter Thiel had long been a looming figure in the technology and intelligence worlds Denny had been exploring. Nippert’s story, then, gave Denny a hook: a way to place Thiel at the heart of a project that, once again, examined just how entangled New Zealand is in the global tech story.

I worked with Denny as a researcher and writer for the project. Embarking on the work in May 2017, we were both clear that, whereas journalists such as Nippert were well placed to map the facts of Thiel’s journey to New Zealand citizenship, we were suited to mapping Thiel’s worldview: a strange, almost anarchic libertarianism with religious undertones, committed to individual economic freedom but rife with seeming contradictions – not least his backing of the isolationist, authoritarian Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential election, and the fact that he is a co-founder of Palantir Technologies, which is at the heart of international and police surveillance systems.

What we didn’t anticipate were the New Zealand-connected rabbit-holes we’d quickly end up down: Thiel’s deep fixation with The Lord of the Rings, for example, or his links to the life-extension scientist and biotech venture capitalist Laura Deming – an expat New Zealander. Then there was the strange story of Wharekauhau Lodge. In the mid-1990s, a group of investors – many of them prominent libertarians – participated in a property deal for a large farm station and luxury lodge in the Wairarapa. Among them were former New Zealand finance minister Roger Douglas and the extreme-libertarian authors of one of Thiel’s favourite books, The Sovereign Individual: How to Survive and Thrive During the Collapse of the Welfare State: the American James Dale Davidson and the late British peer Lord William Rees-Mogg (whose son Jacob is a key player in pro-Brexit British politics).

Denny’s solution to mapping this crazy terrain, thick with complexities – geographic, ideological and fantastical – was to use the language of board games. Over several months, with the help of his studio assistants, he and I learned and researched world-building strategy games and then created rules for new ones, based on the logic of Thiel’s ideological universe. It was important to Denny that the resulting works weren’t just sculptures but working prototypes: games that could, theoretically, be played.

That gameplay made for a pretty grim vision of the future: a chaotic, social-Darwinian, hyper-individualist world in which nation-states collapse and are replaced by a new class of rulers: Sovereign Individuals. To counteract this libertarian vision, Denny decided to present an alternative, more communitarian view of what New Zealand’s future could look like, developing games based on Max Harris’s book The New Zealand Project.

Simon Denny Game of Life: Collective vs Individual Board Game Display Prototype (detail) 2017. Mixed media. Private collection, Auckland

Rather than the “winner-take-all” strategies of the Thiel games, the Harris ones involved physical connection and working together: a giant version of Jenga and a series of woven rugs based on Twister. Unusually for him, Denny also placed himself front-and-centre: making a life-size self-portrait based on the game Operation, from which players could remove all the accoutrements of a young tech-obsessed artist: a VIP conference pass; a bag of nootropic white powder; a vaporiser; some Bitcoin. Denny also invited one of his mentors, Michael Parekowhai, to be part of the show – a Māori artist who had pioneered the use of games in art in New Zealand (just think of his iconic pick-up sticks and Cuisinaire rods) more than two decades earlier, and had made his own self-portrait mannequins in the series Poorman, Beggarman, Thief. Parekowhai’s contribution to The Founder’s Paradox was Acts (10: 34-38) “He Went About Doing Good”: a set of “jack straws” which were strewn across the floor, while one of them propped open the shipping crate Denny’s doppelganger lay inside.

The show opened to significant media interest. Denny, present for the opening and giving a slew of interviews, eventually headed back to Berlin. In the meantime, I took a road-trip with the Irish author and journalist Mark O’Connell, whose book To Be A Machine had laid down one of the breadcrumbs Denny and I would follow in The Founder’s Paradox: his mention of the young New Zealand life-extension investor Laura Deming.

O’Connell and I headed south to track down Thiel’s property in Wanaka. That trip would become, along with the exhibition and the research Denny and I had done, the basis for O’Connell’s subsequent “Long Read”, published in the Guardian, about billionaires prepping for the apocalypse in New Zealand.

O’Connell’s story and, in fact, the project as a whole, reached their absurd conclusions with an unexpected event: the arrival in Auckland of Thiel himself, where he visited The Founder’s Paradox. On the Saturday afternoon that Thiel and his entourage visited Michael Lett Gallery, they also encountered Max Harris: the two subjects of the exhibition, both New Zealand citizens, both with visions for the country’s future, one home from Oxford, one visiting from San Francisco, standing in an Auckland exhibition at exactly the same moment, surrounded by works made about their ideas.

The entire experience, from the show’s inception to its aftermath, was an almost unbelievable chain of events. But they were set in motion, I think, by Denny’s unique working methodology. He is an artist who dives deep, and hard, when he chooses a topic for a project. He works with an incredible speed and intensity – generating a velocity which, at its best, cracks open new connections, new possibilities and new worlds.

My own approach to journalism has been deeply altered by working alongside him – not just by the works he made or the weird happenings they initiated, but by his process too. Denny, I’ve come to realise, is as much a paradox as his work. But he is one of the few artists we have who makes work genuinely of our time – work that not only reflects our world, but sometimes changes it too. And The Founder’s Paradox, I think, shows him at his ambivalent, critical, brilliant best.

Simon Denny Founders Board Game Display Prototype / Founders Rules 2017. Customised Settlers of Catan game pieces, 3D print, UV print on Butler Finish Aluminium Dibond, UV print on card, LEDs, moulded electronic wiring, Dell PowerEdge 1950 server casing, Linoleum, MDF, powder coated steel, Pexiglas / UV prints on canvas. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2018

Simon Denny Founders Board Game Display Prototype / Founders Rules (detail) 2017. Customised Settlers of Catan game pieces, 3D print, UV print on Butler Finish Aluminium Dibond, UV print on card, LEDs, moulded electronic wiring, Dell PowerEdge 1950 server casing, Linoleum, MDF, powder coated steel, Pexiglas / UV prints on canvas. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2018

Anthony Byrt: Let’s start by discussing how the Christchurch version of The Founder’s Paradox will differ from Auckland. Almost all of the works shown at Michael Lett Gallery are included here. But there is one expanded presence: Michael Parekowhai. Why was it important for you to include more of his work this time?

Simon Denny: It’s come out of the reception to the Lett show; what was picked up on and discussed. The conversations about the exhibition showed me that I have a particular body of knowledge, a particular proclivity for a certain kind of production and, let’s say, a particular discourse that I’ve been following for a long time: the tech world, the politics of the people in California responsible for making web-based technology (a US Military invention) scalable worldwide, and how they are intertwined with politics. When it comes to talking about alternative versions of sovereignty and more positive visions for the future, or a deeper critique of what sovereignty looks like in New Zealand, there are other practices that are better at speaking to that. And Michael’s is one. So I really want to foreground his way of framing these questions.

His practice – particularly his game sculptures of the nineties – changed the way I thought of New Zealand. I inherited the idea of using games to look at different versions of what sovereignty could be in the future from my exposure to those works. So to have his presence be a bigger thing in Christchurch was really urgent. Michael and I don’t talk often, but with this project we’ve had these back-and-forths through artistic gestures. I think that’s really special, and it’s a language and a situation that is quite unique. I’ve learned so much from him. It’s nice to continue that conversation through exhibition-making.

AB: It’s interesting that you’re homing in on the idea of sovereignty here, which was certainly embedded in the Auckland iteration of The Founder’s Paradox, but it was more in a globalised, generalised sense – particularly after we discovered the strong connections between New Zealand and the authors of one of Peter Thiel’s favourite books, The Sovereign Individual. Whereas it sounds like you’ve started to think more about the specificities of sovereignty in Aotearoa New Zealand. Is that a shift in your focus?

SD: It’s a clarification. Two directions have come out of The Founder’s Paradox for me, research-wise. The first was the door that opened further into the Thiel-adjacent universe, because I ended up having a conversation with Thiel directly, and that gave me more contextual knowledge of how he works and what his thoughts are on New Zealand. But because of that, I started to ask, if the Thiel-like caricature of sovereignty that I modelled in The Founder’s Paradox sculptures was a model I thought was inappropriate for New Zealand, then what was a more appropriate vision? That’s when I began conversations with people I know in New Zealand who’ve been thinking about these questions for longer than me. I haven’t really made more work about this yet, partly because I’ve realised that what I’m able to speak to as a person, as a researcher, as an artist, has boundaries and limitations. This is why I think my original instinct to include Michael’s work was very important – because it acknowledged that I can’t speak to everything.

Simon Denny Ascent Box Cover Projection 2017. Commissioned painting, oil on canvas. Collection of Frank and Nico McKay, Auckland

AB: How do you start to understand those limitations? Because that seems like a very big shift to me. If I think about Simon Denny from, say 2011 through to late 2017, what I see is this expansive, ambitious, growing, international practice, almost to the point where it became its own ecosystem.

SD: It’s about acknowledging what skillsets I have, and what research I really understand, and then what’s actually better for other practitioners to deal with. I think what I’ve developed in my practice is a critical ability to look at tech conversations of an expansionist global nature, mostly of US origin, which have specific impacts on specific moments through specific products and people that become visible and influential. That’s what I can do, and the tools and methodologies I’ve developed are good for critically questioning and grappling with the cultural implications of large, global technology products that many people encounter and work with. There aren’t a lot of people – in New Zealand at least – that aren’t touched by US designed social media products, Google, and the multinationals that create the boundaries for what our information sphere looks like. That’s a conversation I think I can meaningfully contribute to.

It’s also about pulling back and realising that part of the problem of some of the thinking systems related to the figures I’ve looked into for a long time, figures like Thiel, could be that they drift towards master-narratives as a kind of marketing: large, macro-stories that explain away the world and simplify things. The way systems like Palantir and Facebook work with particular models of data analysis does this too. The people that fund and design these systems are very knowledgeable of how certain kinds of analytic models work, but their discourse seems seldom focused on what those models don’t include, and the types of power that using those models keeps reinforcing. I realised that I wanted to resist that same problem in my work. One of the conversations that came up around The Founder’s Paradox, for example, was about gender. The work includes a number of very male figures. This was intentional, as their way of thinking is something I feel I have the agency to critique. But of course one of the dangers of focusing primarily on these kinds of figures when I’m also male with a particular upbringing, social background and the context that comes with that, is that I might reinforce their ways of thinking, and give credence to those generalising master-narratives.

AB: This is exactly my problem with thinkers like Sam Harris and Jordan Peterson, who are now such big forces in this new pseudo-intellectual universe that Thiel is a part of too. It’s entirely about framing the world in macro terms: women are like this, men are like this, Islam is like that…

SD: Right. And this idea that one can judge people with an IQ test and that it is an absolute, unarguable and objective truth because it’s science. What I learned in looking at alternatives to this – and of course, this is an obvious thing to say – is that science is a belief system, and it’s a belief system that is often used to reinforce old power structures like patriarchy, and capitalism and the growth model that is leading to the exhaustion of planetary resources... These things are not disconnected, and those connections could be discussed more often and more explicitly. Foregrounding this idea in how I present the tech world has been a readjustment for me, and The Founder’s Paradox has the kernel of that. As you say, I think this led us both to look deeper into the logics of the ideas that surround influential people like Thiel, and to realise that those master-narratives, and the belief in data being some kind of objective, truth-like guiding voice, are part of the problem.

AB: Another thing that’s shaped my thinking a lot since The Founder’s Paradox is understanding that the particular kind of “technologism” these guys practice has more to do with religion than science. Their worldviews are ultimately religious frames, particularly if we look at Thiel’s belief in sovereign individualism and life extension. If we fold in people like Google’s Ray Kurzweil and the idea that the Singularity – the point at which humanity creates an intelligence greater than our own – is the inevitable outcome of human progress, you get very clear narratives about ascendance, transcendence, and immortality. Which are completely biblical. And yet these guys hold themselves up as the gatekeepers of a new age of technological Enlightenment and Reason. It all seems deeply old-fashioned and contradictory to me.

SD: Basically what AI is, what Palantir does, and what Facebook does – these are massive, multi-faceted data systems and categorisation strategies that claim to be able to map people. They get to a more and more granular level of categorising our behaviour and tendencies. But it doesn’t matter whether you have two categories or a hundred, because the fact of categorising in and of itself in order to better predict what people will do is part of a system that both limits and accelerates existing power structures.

“Conservative” is a very meaningful word in this intellectual space, because it’s so much about maintaining the status quo: ways of organising that are presented as “natural” because they’re so historically ingrained – like the patriarchy, like men should be doing this, women should be doing that, and I shouldn’t have to bow down to other ways of thinking because this is right and science proves it. Apart from the fact that certain kinds of science are products of that thought system too. This has become clearer to me since making The Founder’s Paradox.

AB: A lot of the thinkers in this space talk about things no longer being about left versus right, because those are twentieth-century binaries unsuited to a globalised, technological world. But I think there’s a big difference between reactionary thinking – which is about keeping power structures as they are – and progressive thinking, which is far muckier and murkier, because it’s about unpacking those existing structures without necessarily having a clear roadmap of what the future looks like. Whereas that’s something the tech-reactionaries definitely have: a big picture of the future they’re creating and want to live in. And it’s built, it seems to me, on the idea that capitalism’s growth curve is a natural law.

Which is interesting in relation to your work I think. Because where there have been criticisms of you in the past is this sense some people have that you’re this capitalist boy playing the global art game, dabbling in Silicon Valley when it suits you and being part of the technological-capitalist system. I know there’s always been a far greater ambiguity in your own thinking about this. But it seems like The Founder’s Paradox might be a tipping point in how you understand your own position and how your value system is perceived by your audiences. Is that fair?

SD: I think so. But it’s also a double-edged sword. On the one hand, I’ve come to a space where I acknowledge my limitations. But that’s also a moment to double down on the things I think I can do. Drawing out the contradictions and problems inherent in these products and rhetorics and thinkers is what I’ve always done, it’s where an important tension in my work lies, and it’s what I can still do.

AB: One of the things that fascinates me about your projects, first as an observer and now as someone who’s been on the inside of one, is their real world consequences. Your 2015 Venice Biennale exhibition Secret Power, for instance, when the Guardian contacted David Darchicourt, the former designer at the NSA, who you’d used in your work. All of a sudden, there was a kind of tumble-down of international journalistic interest, and it became one of the most-discussed exhibitions of the biennale. Something similar happened with The Founder’s Paradox. First, there was Thiel showing up in Auckland to see the exhibition. And second was O’Connell’s “Long Read” for the Guardian about the exhibition and our research. I’m really interested to know how you feel about these real-world consequences of your work, and how you deal with them psychologically.

SD: I try to set up these coordinates, and one kind of has an idea that things are hopefully working on many levels: it’s a sculpture, it’s mapping a system, but it’s also inserting an emphasis into a public conversation that I hope will act as some sort of trigger to extend the work beyond the physicality of an exhibition – to go outside and have a discursive effect as well as a sculptural one. I could never have imagined though, planning in the studio or working with you over the phone and plotting the coordinates, that we’d set up such a waterfall of responses with this project.

I felt mixed about Mark’s Guardian story. I was happy that he’d created a narrative that was meaningful and that put a bunch of issues I felt were important in the show into another discursive space. But it was also interesting to see myself portrayed as a character, which is something that happens when you appear in other people’s stories. It’s never you, it’s always a character. And in my case, it’s an ambiguous character. That was true with the Venice coverage as well. I was portrayed as a sort of both-sides figure: someone shining a light on these things, but who was also perhaps a bit too close for comfort to some of the material.

AB: Do you recognise yourself in that character?

SD: I don’t know quite how to feel about it. It’s because of the line I walk between how I do my preparation and my research and the communities that puts me in touch with, versus what I’m seen to be identifying with and representing. I think that if you really want to understand something and present a reflection on it in a meaningful way, you’ve got to get close to it, and there has to be a certain amount of interest in the figures you interact with. It’s interesting to put that kind of contact and research alongside what people from other communities read into you as a person, and into the output, and what they think is an appropriate way to act. A lot of the nuance in Mark’s piece was about posing those questions. But I know it’s something unresolvable in my work and life.

The more local reporting in the New Zealand Herald about Thiel’s response to the exhibition and then my contact with him just opened a whole lot of other questions: about my role, about what I want out of contact with the subject matter I research – questions that are never answered but continually posited in my process. I think that’s what my work does best. Returning to what my competencies are, and what I can actually do, I think I can pose poignant questions. But I maybe can’t offer answers that are as poignant. I can put things beside each other which lead to productive questions about what’s happening. But I don’t have solutions for those problems.

Simon Denny Operation (detail) 2017. Resin, polystyrene, New Era cap, Adidas mesh long-sleeved t-shirt, Nike Free footwear, acrylic paint, gaming cable, wood, Apple earbud headphones, customised T800 Terminator 2: Judgment Day figurine, fidget spinner, iPhone 5, Kindle Paper, various New Zealand coins, novelty Bitcoin ornamental coins, custom lanyard, nootropic powder in plastic zip-lock bag, Nike bootstraps. Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2017

AB: Mark’s story also played up the doomsday scenario: the bolthole theory of New Zealand as billionaire apocalypse insurance. Given your proximity to the tech world, and the conversations you have with people in the know about everything from AI to blockchain and cryptocurrency, what are your thoughts about where things are headed? Are the likes of Thiel leading us to a political apocalypse or technological dystopia?

SD: It’s very clear already that certain communities that develop and market web-related technology have changed the discursive space, and I think it’s become clear how this has changed effective public storytelling. It’s also very clear that the cycle of attention and what gets internalised and discussed at scale is different, and behaves differently than it used to in earlier information environments. I think the people, like Thiel, who are closest to the creation of these new technologies, understand this very well, while there’s a lag of understanding that happens down the line, in the general public, but also in other, maybe more liberal, “elite” political factions. But I guess that’s also a very old story of power.

This whole conversation – which touches on the Sam Harris/Jordan Peterson issue – is about using identity as a tool that can accentuate division, which is accelerated by Facebook – because Facebook itself is based on categorising identity, and targeting those categories. That’s an advertising thing, that’s a data science thing, that’s a predictive modelling thing. If this accelerates more, and there’s a consolidation of power by figures like Trump who are so good at gaming these information structures, then I think we’ll go to a very dark place. But there are a lot of pushbacks. There’s pushback from people who see things differently. And there’s pushback from the planet. It’s been the hottest summer in Europe I can remember, and it’s no joke. To help me think about these things, I’ve enjoyed learning more about Vivian Ziherl’s Frontier Imaginaries, and the discourse around Kate Crawford’s AI Now institute. And I’ve given Wendy Hui Kyong Chun’s work a closer reading.

Another thinker I’ve drifted towards is Donna Haraway. I’ve been familiar with her work since I was an undergraduate, but I recently got really into her book Staying With The Trouble, and looking to the way she frames identity beyond single species, as well as her ideas of kinship. These are ways of thinking I hope will gain more traction, and I hope will be a bigger part of designing the systems of the future. But there are strong conservative forces that have a lot of power, and that don’t care at all about those kinds of conversations. I think if you take climate change seriously, it’s hard not to trickle down to something like the way Haraway frames life on the planet, questioning what the accelerating and normative forces are that keep the old systems going. It’s like, yeah, we can keep doing this, but this is what it’s going to do. The planet could benefit from a holistic reassessment of which systems get to scale up in the future.

AB: Which is the absolute opposite of where we are right now, with the Trumps and the Thiels, who have a deep commitment to the industrial, technological and capitalist forces of the past 150 years.

SD: Positions like Thiel’s seem consistent with those of previous powerful industrialists. This is also true for Trump I think. Coming of age and moving away from New Zealand at the beginning of the Obama era, and living through that era in Germany (not so long ago still partially occupied by the US) surrounded by US expats as I was growing my practice, I had one narrative of the world, which is that it was moving towards something more diverse, open, integrated and liberal with a figure like Obama in power. His story seemed to be so much about history moving in the “right direction”. And then we arrive at this moment where Trump comes in, which felt to me like a rupture in November 2016.

But now I think, and the more I learn – and a lot of people have been much more aware of this for a long time – it’s actually not a rupture; Trump is continuity. And Thiel is continuity. And that’s what I hope we can rethink. But I had to see it in those terms first.

Simon Denny Founders Board Game Display Prototype / Founders Rules (detail) 2017. Customised Settlers of Catan game pieces, 3D print, UV print on Butler Finish Aluminium Dibond, UV print on card, LEDs, moulded electronic wiring, Dell PowerEdge 1950 server casing, Linoleum, MDF, powder coated steel, Pexiglas / UV prints on canvas. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2018