Of Braided Rivers and Hydro-Traders

Water and Art in Canterbury

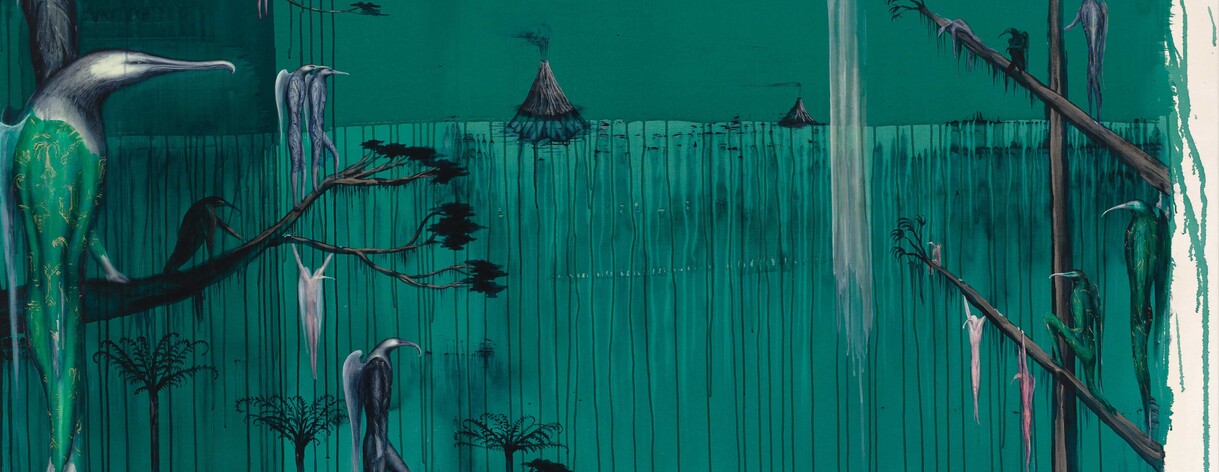

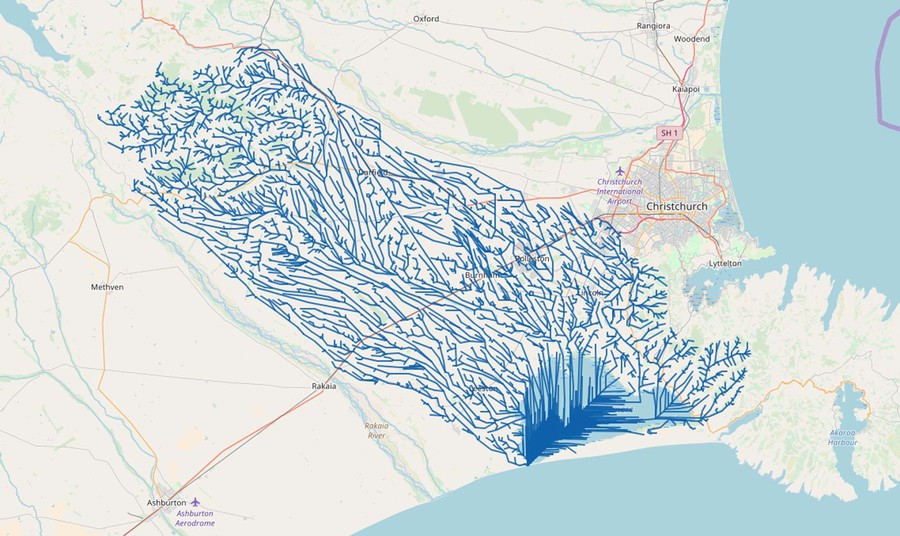

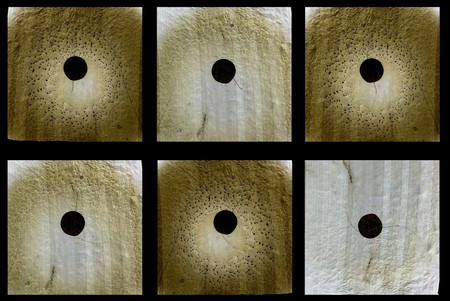

Visualisation of all waterways that drain into Lake Ellesmere. Image courtesy: Niwa

“With 14,000km of coastline, over 180,000km of rivers, and 3,820 lakes, there’s more to the land of the long white cloud than land…” So began an advertisement in a recent Sunday Star Times. It might have been the opening gambit for a campaign devoted to water conservation but was, in fact, a promotion for the latest model jet ski: “And all you need to unlock it is the all-new Yamaha Waverunner FX HO… SAME PLANET, DIFFERENT WORLD. Yamaha-motor.co.nz.”

The Waiau River from space. Image: Google Earth

Rivers mean different things to different people – be they hydrotherapists, water-traders, keepers of tribal wisdom, watercolourists or riders of jet skis. In our era of rapidly expanding dairy farming, adventure tourism, fresh-water bottling, fly fishing and ecotourism, the multifarious and often competing uses of rivers have never been more apparent. And rarely have these conversations been more animated than in the Canterbury/Otago region, especially since the recent influx of, to borrow a phrase from the eco-protestor’s handbook, “big irrigation, more cows and polluted rivers”.

Among a small number of braided river systems still in existence globally (others can be found in Nepal, South America and, heavily modified, in Italy), Canterbury’s waterways offer a salient metaphor for the delicate wider ecology of Aotearoa New Zealand and, as Hamish Keith stated in his 2007 television series and book The Big Picture, for the country’s population. The series concluded with an aerial view of the Rakaia River plain which, according to Keith, mirrored the current state of multicultural New Zealand, with its “countless braiding threads … different currents, depths, directions and colours”.

In fundamental ways, issues surrounding water are currently being rethought at many levels of society – a case in point being the 2017 granting of legal ‘personhood’ to the Whanganui River. Yet any newly heightened awareness of the importance of water has to be qualified by the invariably bleak prognosis offered by scientists – according to one recent report, 43% of New Zealand lakes and 84% of pastoral catchments are polluted; 68% of ecosystems are degraded. With the further expansion of dairy farming, these statistics can only get worse.

Among the recent art projects drawing attention to issues surrounding water, Ashburton Art Gallery’s The Water Project (April until June 2018) engaged a group of thirteen artists to, in the words of curator Shirin Khosraviani, “explore the cultural, conceptual and imaginative qualities of the rivers, lakes, wetlands and freshwater systems of Aotearoa New Zealand”; bearing in mind that “in an era of ramped-up environmental degradation, water is being reconsidered as a natural element essential to our wellbeing and as carrier of histories and traditions, myriad individual and collective meanings”.

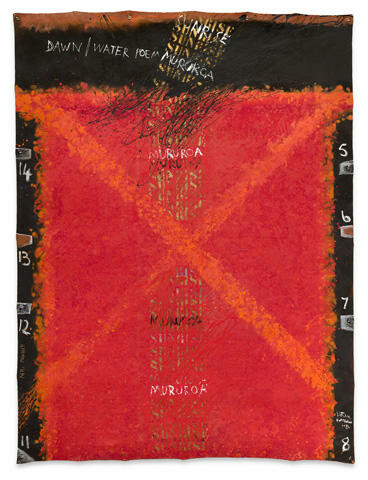

Water might be a hotly contested issue at the present time but as a subject for art it goes way back: “Be praised, my Lord, through Sister Water,” wrote St Francis of Assisi in his thirteenth-century “Canticle of the Sun”: “She is very useful, and humble, / and precious, and pure.” Praise of pure water was a common theme in traditional Gaelic poetry – as it was and is in many other traditions, including that of Māori. In On going out with the tide, Matire Kereama described the Te Aupouri tradition of dunking a newborn baby in the cold river daily – a task given to the grandmother and deemed crucial for the child’s physical and spiritual well-being. For a contemporary Māori angle on the topic, you could start with Hone Tuwhare’s aptly named poetry collection, Deep River Talk. Colin McCahon’s preoccupation with the spiritual element of water went as far back as The Virgin and Child compared of 1948 and permeated his later Waterfall series and the oceanic meditations that emerged from his Muriwai Beach studio towards the end of his career. Late works such as A Letter to Hebrews (Rain in Northland) and Storm Warning are a theologically driven immersion in the planetary water cycle.

Waterways flow through the history of New Zealand art, from the cave art near Duntroon (which Water Project participants visited) to the work of William Hodges, Petrus van der Velden, Sydney Lough Thompson, Trevor Moffitt, Joanna Margaret Paul, Pauline Rhodes, Mark Adams, Gaby O’Connor and more. Phil Dadson wrote memorably, in the wake of a voyage to the Kermadec Islands in 2011, of his realisation, mid-ocean, that the human body – which is made up of over 60 per cent water – moves in accord with the tides and movements of the hydrosphere. Water is not something we are separate from.

Ross Hemera Ko Kārewa te Whakarare 2018. Alkathene pipe, raffia, river stones, charcoal, kokowai

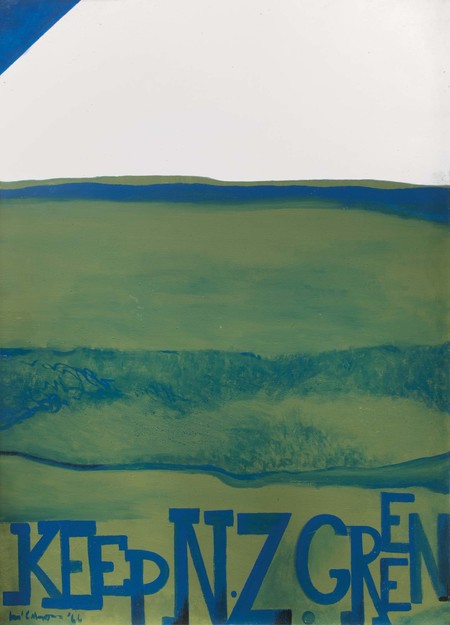

Colin McCahon Keep New Zealand green 1966. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. Private collection. Reproduced courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

WATER FEATURE

The Water Project began with a day-long seminar/ hui in Christchurch in March 2017, during which the artists involved and other interested parties heard from scientists, conservationists and iwi. Alongside much celebration of the river systems so beautifully charted in a NIWA map of the region, the discussion was haunted by the spectre of neo-liberalism, with its hard-nosed commodification of natural resources. The stated corporate objectives of dairy giant Fonterra were cited, the Three V’s: “Value, Volume and Velocity”. One speaker felt compelled to agree with J.R. Neill’s gloomy assertion that, over the past two centuries, “the human race, without intending anything of the sort, has undertaken a gigantic uncontrolled experiment on the earth”. Another quoted Northrop Frye’s indictment of the Western world’s obsession with progress and production as “the conquest of nature by an intelligence that does not love it”.

The seminar was followed by a five-day tour of the Canterbury region, with artists meeting various experts, visiting sites and trying to get their collective head around some very complex river systems, floodplains, aquifers and the myriad lifeforms which inhabit both underground and terrestrial waters. Along the way, the group couldn’t help but notice the many kilometres of pivot irrigators that lined the roads of rural Canterbury. Also notable were the massive human-made water storage ponds, constructed to syphon off river water after heavy rain – this despite the widely-understood fact that river ecosystems need to flood periodically to renew and cleanse themselves, to move boulders and to maintain their coastal outlet.

The objective of the Water Project was, as Khosraviani noted, to provide a timely and necessary “catalyst and a forum for discussion in the wider community about how we think about and inhabit the natural world”. Two months into the exhibition period she reported that responses had been mixed: “We have had angry people who have called the show ‘aggressive’ and we’ve also had people moved to tears by the works. I have been reminded by some that ‘dairy built your art gallery’ and others have spent time and truly appreciated the different voices and perspectives in the show.”

In tandem with the need to protect waterways, social scientist Charlotte Šunde, spoke to the seminar of the need to nurture and cherish the discourse around rivers. The vocabulary needs to be protected from, or reformulated in opposition to, “the alienating narrative of the status quo”, with its plethora of pseudo-technical and business-friendly terms. A new terminology was, she said, flooding the land – “hydro-trader”, “flood-harvester”, “functional landscape” – words which were “a scaffolding propping up a specific way of seeing reality”. She prescribed a programme of “word rescue” as part of the riparian project, and suggested a good start would be to stop referring to rivers and water as a “resource” and move away from the notion of the functional landscape in which invariably “the land rules the stream”. Rethinking verbal and visual approaches is, as numerous commentators agreed, a crucial part of re-engaging with and re-animating the subject. Later, artist Ross Hemera spoke of the need to renew our intimate relationship with water, to rediscover lost wisdoms and rites – “to know what eel to take, and what time of year to take it.”

In a comparable spirit, New Zealand poets have celebrated both the impurity and the purity of water – qualities which are not necessarily mutually exclusive. M.K. Joseph, in his 1959 poem “Distilled water” highlighted a quintessential, life-enhancing impurity:

Consider now the nature of distilled

Water which has boiled and left behind

In the retort rewarding sediment

Of salts and toxins. Chemically pure of course

Tasteless and flat. Let it spill on the ground,

Leach out its salts, accumulate its algae,

Be living: the savour’s in impurity.

On the other hand, James K. Baxter’s “Winter monologue” of 1971, concludes with a paean to pure water : “…water is the sign of God, / common, indispensable, easy to overlook… / time then to soak myself in / the hot springs of Heaven!”

For a dramatically different artistic treatment of water – but one attuned to its present-day commodification – you could look to Michael Stevenson’s installation at the 2003 Venice Biennale, which featured, alongside a Trekka, a little-known piece of homegrown technology known as a “Moniac”. In the accompanying catalogue, curator Robert Leonard elaborated:

Seven feet high, four wide, and three deep, the MONIAC was the brainchild of New Zealand economist Dr Bill Phillips. This perspex labyrinth is a high-tech, hydraulic model of the economy, a water-driven analogue computer. Phillips created it in 1949, while studying at the London School of Economics, where it was used in class to demonstrate Keynesian macroeconomic theory. Water represents money in circulation. By regulating its flow using gates and valves – reflecting interventions in the economy – complex downwind effects can be observed and plotted.

If the economy can be understood in terms of the flow of liquid, so can a myriad of other aspects of human and non-human life – a point made by Hemera who told the group of artists, on the rocky foreshore of Lake Pukaki, there was a saying in Māori, “Ko wai koe?” which means “Who are you?” or “Where do you come from?” But there was a further translation he drew attention to: “What waters are you from?” Water defines our identity – past, present and future – as well as permeating our physical being.

Euan Macleod Swingbridge 2018. Acrylic on canvas

Brett Graham Plus and Minus (detail) 2018. High-definition digital video, 7 mins 15 secs. Sound and editing by Dan Mace of Remote

FOR AND AGAINST A GREEN WORLD

A clean-cut, youngish man sits on a grassy mound, leaning against the trunk of a tree: a modern-day Johnny Appleseed or a dramatically tidied-up version of the archetypal nature-poet – think Baxter, with a dash of Keats and Whitman. Instead of writing in a journal, he is tapping away on a laptop, the screen of which is dominated by six irrigation circles, seen from high above. The circles are arrayed like wheels or dials in some Utopian – or, depending on your viewpoint, diabolical – machine.

This image – in hyper-real yellows and greens – is prominent on the website of the irrigation manufacturer Bauer. Beyond the upraised laptop screen, an irrigator arm extends outwards into what looks more like a heavenly kingdom than a farm. The Bauer Boy is clearly in the business of overseeing or delivering a dream. His mission, like that of the archetypal Romantic poet, is not only to enhance and improve nature but also to humanise it. Entering stage-left, a sky-blue tag announces: “BAUER – For a green world”, a slogan that has become increasingly familiar to any motorist travelling through the South Island on account of its trademark appearance on much roadside hardware.

In New Zealand over the past few years, the word and colour ‘green’ has taken a hammering. In the 1960s, when Colin McCahon painted Keep New Zealand green and artists like Michael Illingworth were instrumental in the emerging ‘Green’ movement, the colour was associated with untrammelled, rejuvenating nature. Since then, its status has become increasingly problematic. Greenness – while being central to photosynthesis and, accordingly, to life on the planet – has lately also become synonymous with the expansion of dairy farming and intensive irrigation. Across the ochre and brownish lands of McKenzie Country – lately rebranded as “the McKenzie Dairy Frontier” – or around the edges of Central Otago, the cogs of the Green Machine churn onwards. Not far from the town of Tarras, an hour north of where I write this, the skeletal architecture of a water irrigator, maybe a kilometre in length, is parked along the verge of State Highway 8. From the window of our car, the hills beyond are seen through a matrix of aluminium pipes, dripping nozzles and bracing.

These overarching structures stalked the Water Project exhibition, as they do the Southern flatlands. Hemera’s Ko Kārewa te Whakarare comprised lengths of black plastic irrigation piping, shaped and woven into the form of a waka, inside of which were placed river stones. Similar piping was moulded into outsized bovine form in Jenna Packer’s Pipe Dream – a work which also referenced the ‘bull market’ of international finance and the ‘John Bull’ personification of colonial England. The aerial view of irrigator circles featured in the Bauer advertisement is given a less romantic treatment in Brett Graham’s Plus and Minus. Using drone footage, the multi-screened work presented numerous aerial views of an irrigator spraying water and effluent onto a 26 x 26 metre frost cloth.

Just beyond Tarras, a gigantic coat-hanger is parked alongside the road. The owner has constructed earthen mounds so the wheels of the irrigator can gain sufficient height for the network of metal beams and pipes to clear the rooftop of his house. The farmer and, presumably, his family go about their daily lives beneath the intermittent shadow of its long arm. Same planet, different world.

"Fifteen apparitions have I seen; The worst a coat upon a coat-hanger"

(W.B. Yeats, "The Apparitions")

Conversation with a Mid-Canterbury Braided River

Moved, as I am

immovable, like you

I turn over, I sleep

on my side

nestled in the

watery fact

of you. I fall about, collect

my thoughts –

another thing we have

in common – I get ahead

of myself, I meander

so as not to

lose my way. I rock

and sway.

I digress. And this is how

I come back to you

bedded and besotted, body strewn

with inverted clouds

migratory birds, dawn-lit

improbable.

Like you, I have

my sources; I wade

the long waters

of myself. My ear

to the ground or

the constant applause

of your rapids. You are your own

concert, open-air, a solitary leaf

crowd-surfing downstream

and the occasional beercan

thrown from a passing car. Lately there

has been talk of you as

lapsed or recovering, dispersed

drained, interrupted or

resumed. And this

my sleepless night, my apparition:

an insect walking this land –

a coat-hanger on which might

hang a bright green shirt, a stream led

down a long avenue of hosepipe and

aluminium, a river flowing

sideways, its taniwha

reduced to a drizzle or fine mist

a trickle from

an automated tap. Your position on

this too is inarguable

as if argument was ever

a river’s way.

Braided, you tell me, I was

upbraided, scrambled across

siphoned and run ragged by hydrotrader, flood

harvester, water bottler, irrigator

and resource manager. This riverbed is

my marae, the long legs of wading birds

my acupuncture, these waters

my only therapy.

On clear nights

galaxies enter me, planetary bodies

like swimmers. How many minds

a river has – caddis and mayfly

eyeless eel and

native trout. As an argument

this might not hold water

but neither does

a paddock gone around

in circles

or a skeletal arm endlessly

scrawling its initials in

a sodden green ledger. Whichever way

the river doesn’t flow

I remain undecided, as is

water’s way.

I disperse, lost for words

I dry up.

I saw an apparition, an insect

walking this riverless land

earthbound stars

rattling, beyond reflection

along a dry

river’s bed.