Looking at Forty Years of Māori Moving Image Practice

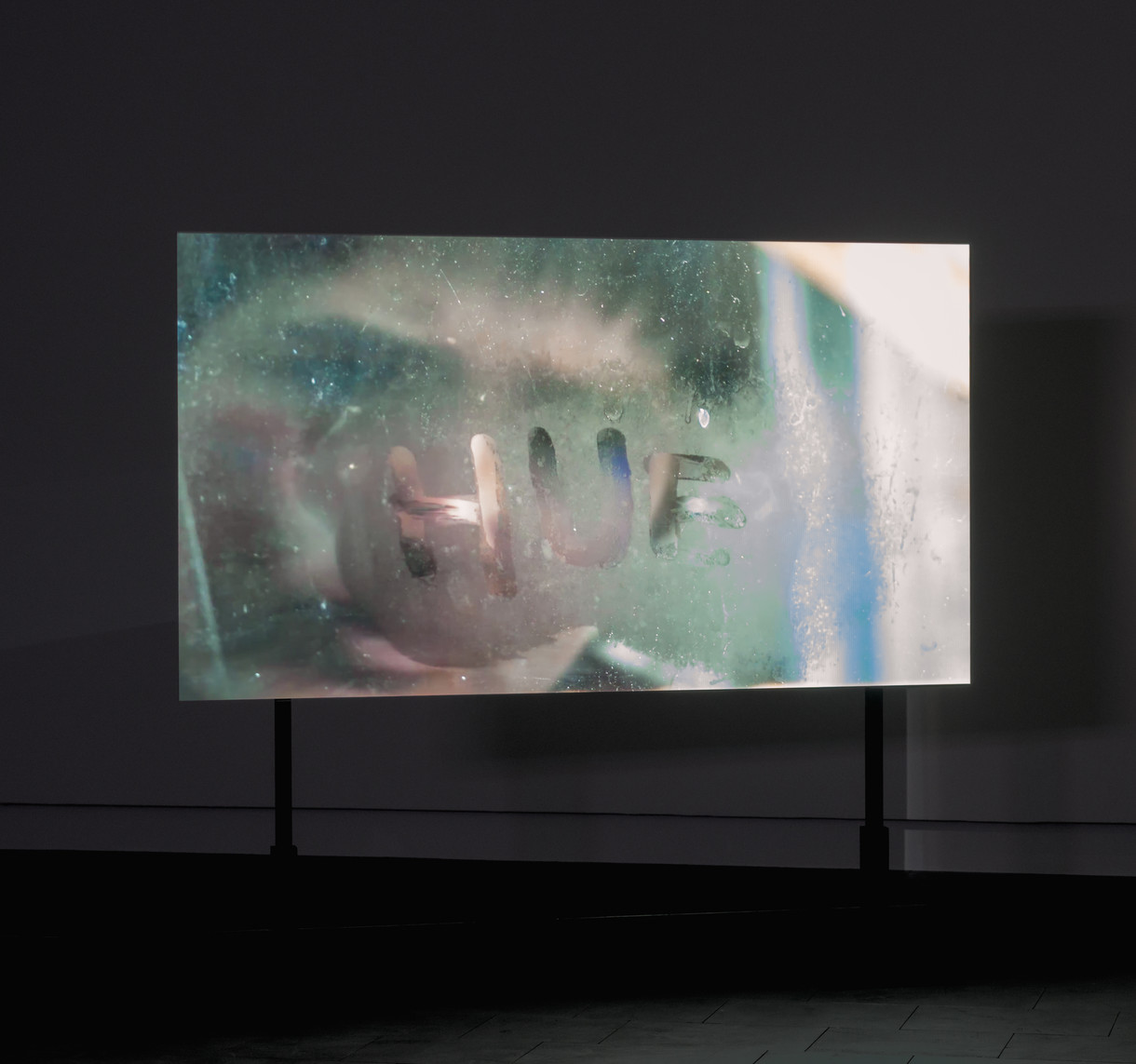

Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive. Installation view, the Dowse Art Museum, 2019. Photo: John Lake

Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive is co-curated by Bridget Reweti and Melanie Oliver. The following text is a conversation between the two curators around co-curating, archives and Māori moving image practice.

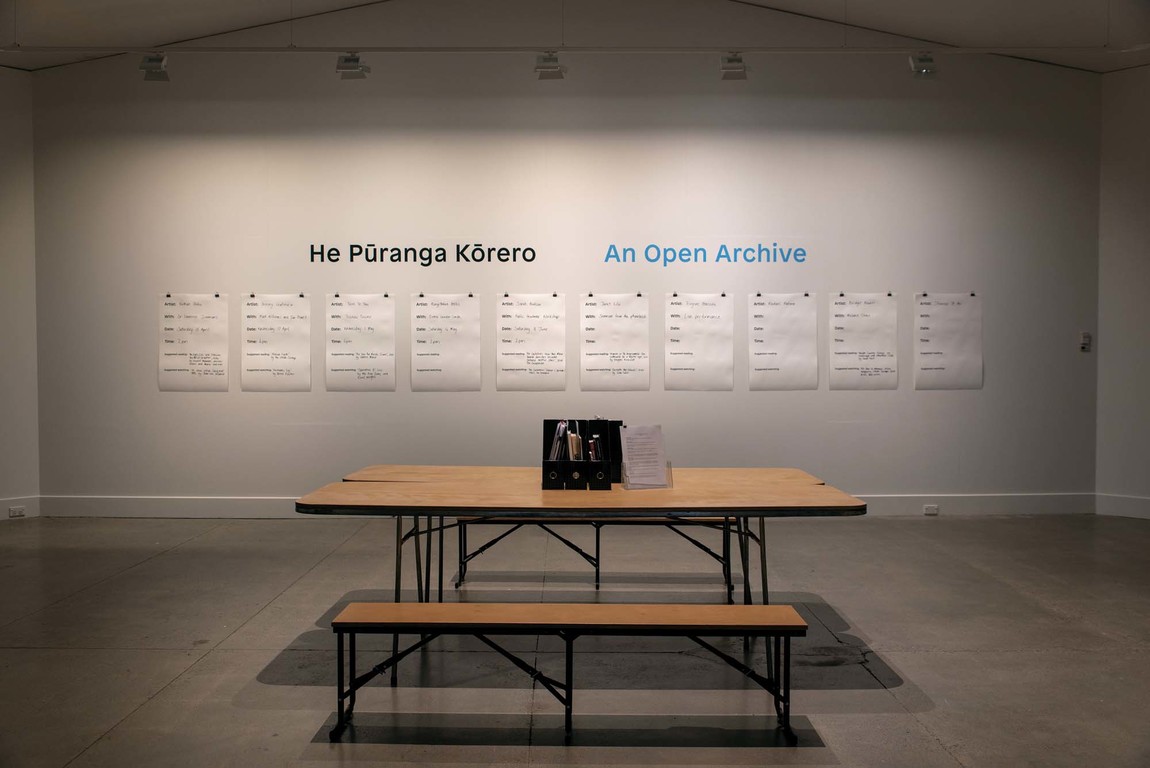

Bridget Reweti: The exhibition Māori Moving Image has an experimental aspect – it’s in the second half of the title: An Open Archive. For this part of the show, we tried to source as many texts about the twenty featured artists as we could. We knew we wouldn’t find everything written or published and that this would be an ongoing process. But we also learnt that there was very little published material about most of the artists. Within this space, or lack thereof, we recorded a series of talks, round-table discussions and performances that would contribute to the archive. What do you think we should do with the recordings?

Melanie Oliver: The exhibition certainly felt like a different way of curating. The archive space provided an opportunity to make public the research processes that generally sit behind an exhibition; a chance to ask questions and invite responses from the arts community instead of presenting a fully formed argument. Through the public programme, the ongoing conversations with artists, curators and interested participants echo the private discussions that usually inform the curation of an exhibition. So I think the documentation of these events needs to also become a public archive in some way, but it is not a finite resource. A print publication is perhaps the simplest way of distributing information, but the exhibition is not positioned as complete or authorised and incorporates the views of many others with wide-ranging knowledge and experience. As a living archive, an online forum could be best?

One of the aspects that you were particularly keen to include was the list of things that artists felt inspirational for their work – the suggested documents to read or watch – as a way to show the variety of influences and connections for practitioners. What did you expect to come out of this?

BR: We asked for a number of suggested texts from artists; whether films, essays or books, they were a way to show audiences what Māori artists are inspired by. I’m focused on allowing the diversity of Māori research interests to highlight our varied lived experiences. I think it’s important to provide points of access into an artist’s practice and, by learning their area of interest, provide another spark of connection. There were both national and international art theory texts sitting alongside RNZ web series and programmes from Māori Television. So while the archive holds texts about the artists’ work, the influences they suggested help to further unpack the depth of their work and practice. Did you come across any texts in the archive that broadened your understanding of an artist’s practice?

Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive. Installation view, the Dowse Art Museum, 2019. Photo: John Lake

MO: Definitely. The archive brought to light a lot of interesting texts for me and helped me to better understand some of the concepts that are foundational for Māori artists. There’s an early essay by Lisa Reihana that outlines the importance of moving image practice:

Māoritanga is not stuck in a nineteenth-century world view. Film and video is the major medium in which people now receive information, this medium has an important role to play in teaching people ways to perceive our culture. Māori filmmakers accept this responsibility as part of their kaupapa; and are constantly pushing boundaries, ideas, and ways of seeing ourselves, not only with Pākehā but also with other Māori.1

I really enjoyed the texts on the CD-ROM catalogue that accompanied the landmark exhibition Techno Māori (2001), and Maree Mills’s writing in the Aotearoa Digital Arts Reader (2008) provided a great description of the beginnings of contemporary Māori women’s new-media practice. Deidre Brown articulates well the significance of the architectural structure of the whare in her text ‘The Whare on Exhibition’ (2004), which documents also the important Whare exhibition that she curated in 2002. Of more recent publishing, I found writing by Cassandra Barnett and Natalie Robertson in Animism in Art and Performance (2017) was also enriching. And lastly, Rachael Rakena’s master’s thesis was particularly helpful. It’s not often that you get around to reading academic documents, and in this she provided a clear sense of the kaupapa that underpins her work. Rachael created the term “toi rerehiko” to describe her moving image practice – “art that employs electricity, movement and light”. For the work that we included in the exhibition, ...as an individual and not on behalf of Ngāi Tahu (2001), the depiction of water overlaid with a string of email communication created an insightful metaphor for new forms of connection; a way of considering how we converse and find belonging in a contemporary world.

Something that I hadn’t expected from the exhibition was the way that the quality and texture of the images would shift across the different formats. The technological aspect of each work was sometimes challenging, securing a 16mm projector or a CRT monitor for example, but the way the images looked on these different apparatus surprised me – the richly textural, sculptural aspects of moving image practice.

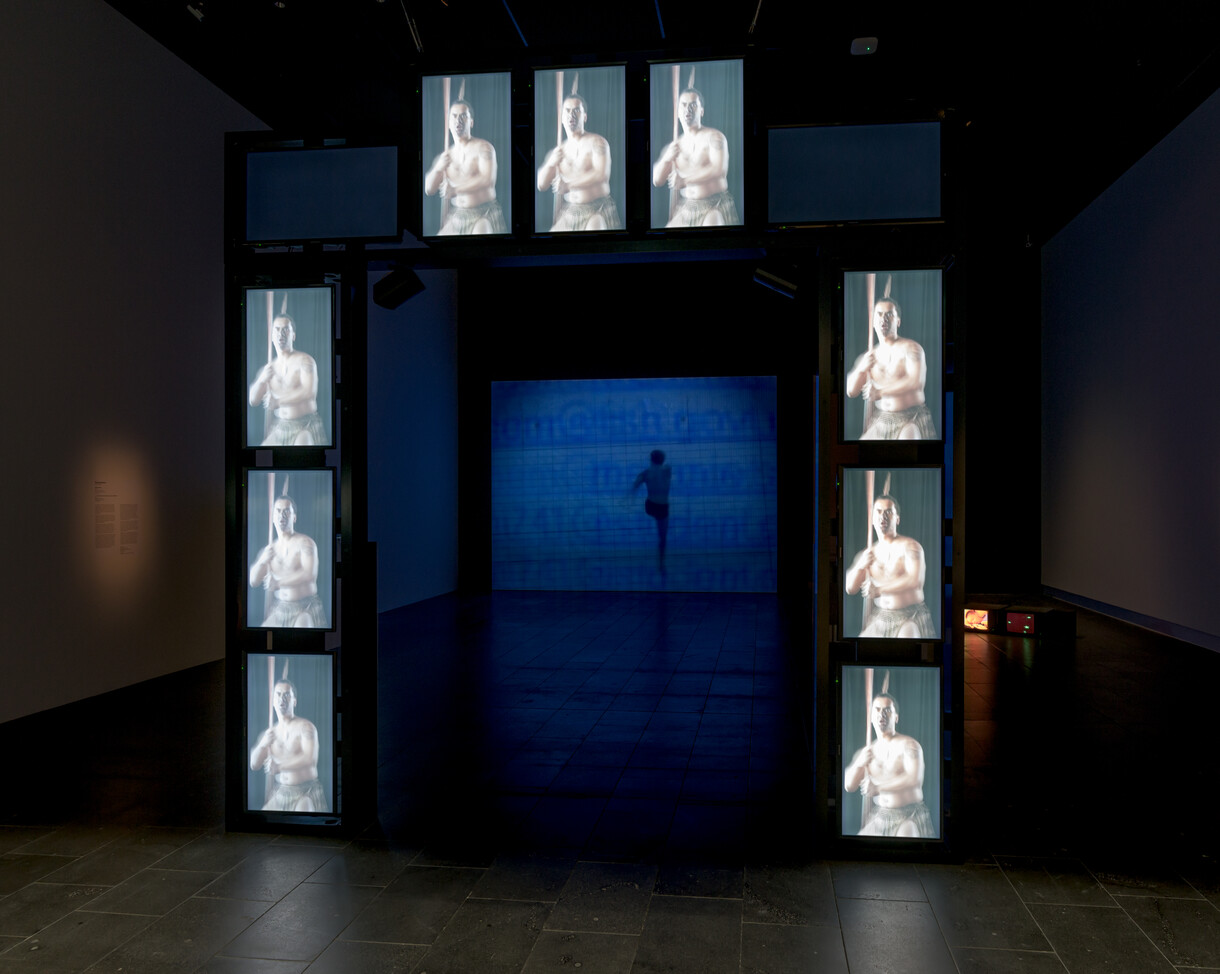

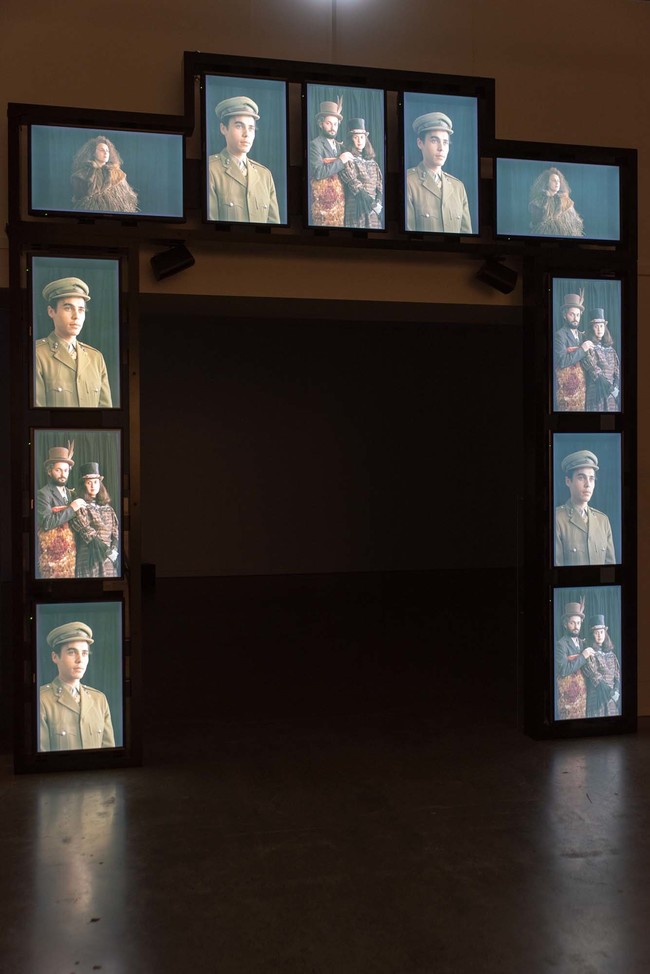

Lisa Reihana Native Portraits n.19897 (1997). Eleven-channel video waharoa. Courtesy of Te Papa Tongarewa. Photo: John Lake

BR: There are so many practical spatial elements to consider when exhibiting multiple moving image works. Showing works on the formats they were made for is important to maintaining their integrity. This is also true for giving the works space, especially in terms of sound and light bleed. Whilst it is somewhat inevitable that ambient sound from one work will be present when viewing another, it’s incredibly important to spend time getting the sound levels right; making sure the works are in conversation and not competing. We’ve spent a lot of time discussing how to exhibit as many Māori moving image artists as possible, whilst honouring their work with space. What did you think about these curatorial challenges?

MO: People sometimes think that showing a video is easy… and I would completely disagree! As you say, exhibiting moving image works alongside each other is tricky at times, and spatial considerations are key to ensuring the works are seen in the way the artists intended. Some need to be given a cinematic environment, others are better at a more intimate scale; some are immersive experiences, others can be viewed on a simple screen. With the first iteration of the show, we hoped that the rotating schedule would encourage visitors to return and spend time with the works. Time-based art is demanding in that sense – you need to sit with it (although a good painting will make you do that too). It’s very exciting that there is enough space to present all of the works simultaneously at Christchurch Art Gallery though, as this will enable us to read them together and form new connections.

The collection of video or time-based media is challenging for institutions for a number of reasons, so it’s been a good opportunity to bring out a number of historical works that might not otherwise be seen alongside contemporary practice. As a moving image artist yourself, what do you think about the difficulties of collecting and archiving video?

BR: To be honest I’m not sure how often this actually happens, but as artists we need to be archivists as well. Backing up works and migrating them to different formats, whilst maintaining the integrity of the format they were originally made and shown in is incredibly important, but difficult once you’ve moved on to a new project. Which is partly why the institutional collecting of moving image works is so essential. Christchurch Art Gallery acquired Rachael Rakena’s Rerehiko (2003) from one of their opening exhibitions in 2003,Te Puāwai o Ngāi Tahu. And when we knew Māori Moving Image would be shown at the Gallery, there was enthusiastic discussion about being able to show Shannon Te Ao’s Untitled (Malady) (2016), which they had recently acquired. However, collecting moving image works is a slowly growing practice; Lisa Reihana’s Native Portraits n.19897 (1997) and Robert Jahnke’s Te Utu (1979) are on loan from Te Papa and Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision respectively, but all other works have been provided by the artists themselves. As an online platform, I think CIRCUIT has been really helpful for a number of artists in assisting with the visibility of and critical discourse around their practice.

In order for more works to be collected, they need first to be exhibited, which is a significant aspect of Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive in that we cast our net as wide as possible to show as many important works from Māori artists as we could find. This exhibition is the first of two and in the second iteration we plan on commissioning new works and producing a publication to document and support it. So it’s exciting times!