Te Āhua o te Hau ki te Papaioea

Terri Te Tau Te Āhua o te Hau ki te Papaioea 2015. Suzuki Carry van with projection and sound. Music composed by Rob Thorne. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: John Lake

The ‘Operation 8’ anti-terror raids in October of 2007 were the culmination of a police investigation that led to the raiding of homes across New Zealand. The raids were conducted after an extended period of surveillance, which was enabled through use of the 2002 Terrorism Suppression Act. In 2013 the Independent Police Conduct Authority found that police had “unnecessarily frightened and intimidated” people during the raids.1

In Noti Teepa’s reflection of that time in The Day the Raids Came she mentions noticing that one of her mokos kept looking to the corners of the whare.2 She understood this to be a sign of ongoing trauma from the terror raids. Noti’s reference to the “corners of the whare” invokes a well-known whakataukī which takes on a hauntingly different aspect when viewed through the context of surveillance: “He kokonga whare e kitea, he kokonga ngakau e kore e kitea – The corners of a house can be seen, but not so the corners of the heart.” Sixty homes were raided during Operation 8, and in each home every corner was carefully scoured in search of evidence to support plans for terrorist activity. But after one-and-a-half years of surveillance the intentions of those targeted were still unclear – the corners of their hearts remained unseen. The people caught up in the raids were Māori and allied activists, and the predominant narrative written by those responsible for leading the investigation was framed around terrorism – this was the lens through which all activities and data were viewed. This terrorist narrative, however, was far removed from my personal experiences of the people who were implicated and for me it raised questions around what we assume to be empirical evidence derived from surveillance data, and how susceptible it is to cultural bias and prejudice.

My memories of the morning our house was raided are a bit fragmented after twelve years. My partner Teanau Tuiono had arrived back in the country the night before. I remember our sixteen-month-old running in to wake us up in the minutes before the police knocked on the door; a crowd of police holding a search warrant that said they were searching for guns and other weapons; being questioned in our bedroom while I breastfed our three-week-old and the officer cutting it short because I think he felt uncomfortable; another officer – the only woman – standing by my bedroom door looking really apologetic; being asked to leave my bedroom so they could search it; going to the kitchen to feed the toddler breakfast while one of the Pākehā officers talked about how cool it was that we spoke Māori to our boy and how more people should learn; Teanau cracking a joke when someone was searching through the nappy bucket that “the only pū you’ll find in there is the crap on my kid’s nappy” (pū is a Māori word for gun).

There were police everywhere inside and out, going through the sheds and backyard. I hid my feelings away during the raid but became upset afterwards when I saw that our family photos, old letters and personal things were tipped over the floor and bed. The real frustration and worry came in the days that followed as I tried to understand how friends and acquaintances could be facing charges of terrorism.

When family and friends asked why our home had been raided, my standard answer was that it was about my partner’s activism – his involvement with, and support for, indigenous and marginalised communities in different struggles – and also the fact that he’s really good at facilitating connections between people. I felt that perhaps it was something an agency dedicated to finding terrorists might deem suspicious – Māori Tino Rangatiratanga activists hanging out with Pākehā snail-saving environmentalists? Dodgy, right!

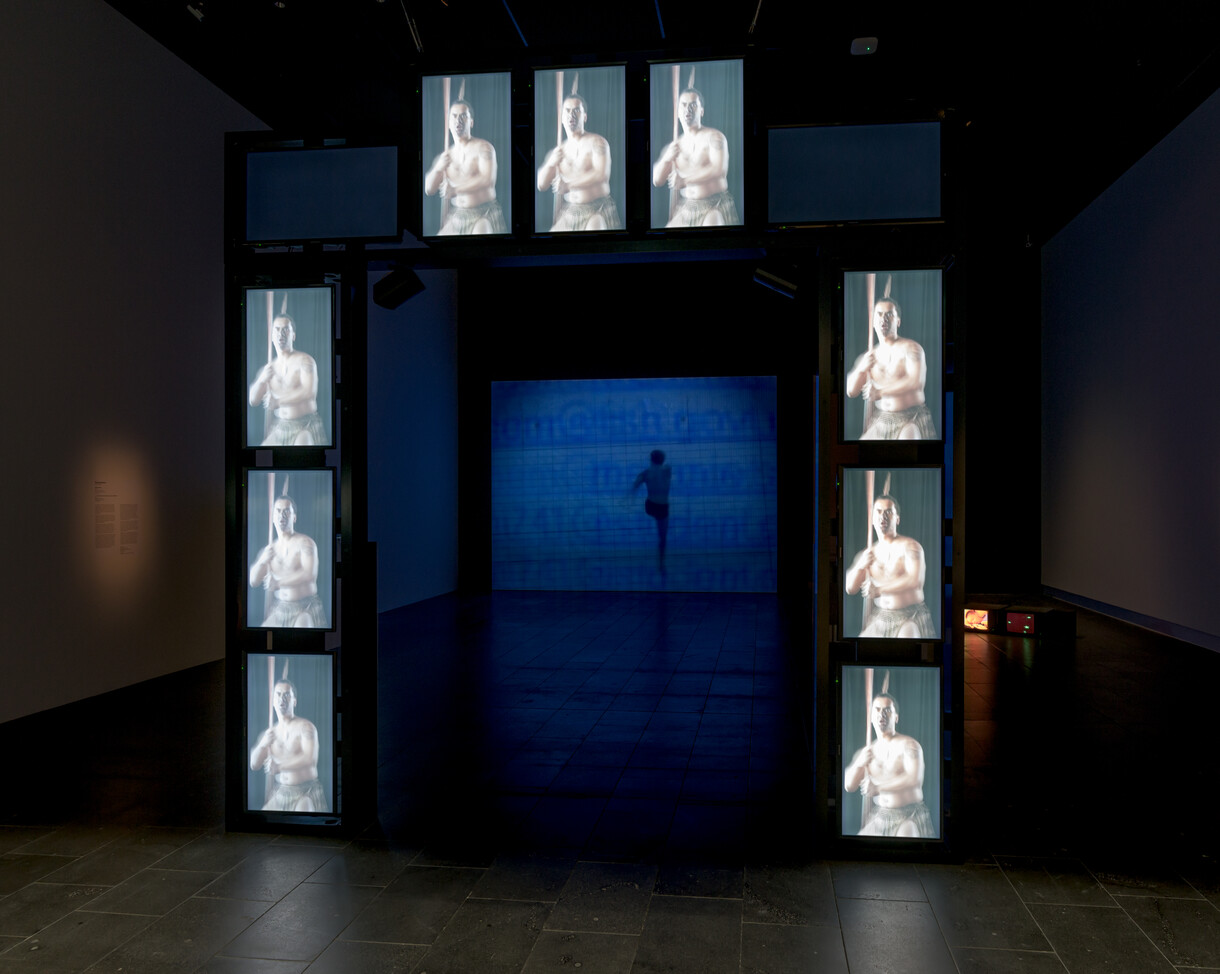

Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive. Installation view, the Dowse Art Museum, 2019. Photo: John Lake

My answer to that question now would be simpler. Operation 8 and the raids were the result of racism. Around the same time I remember there was an image floating around online of the National Front; a group image of white men all holding their guns. They were very open about their hateful ideology, but savvy enough to know they didn’t need to worry about being the subject of a police investigation. That’s a reality that has been brought into brutal focus by the Christchurch terrorist attack and the revelation that in ten years of state surveillance there was no mention of White Supremacy.3

When people become aware that they’ve been under surveillance and part of an investigation it can open a psychological door that’s hard to close, causing them to modify or guard their behaviour. This can be related to the forms of surveillance that we experience in everyday life, such as speed cameras; when they are known or visible these can act as external motivators, a way to remind us that we’re seen and accountable. At the extreme end this form of surveillance can take on a dystopian Black Mirror quality, but it’s worth thinking about, especially as systems like China’s Social Credit are increasingly utilised.4

The presence of surveillance as an external motivator raises questions about the possible effect on intrinsically motivated actions like self-direction and benevolence, which are often associated with challenging convention and the status quo. This is of particular concern when such systems are disproportionately focused on Māori, Muslims, migrants of colour and activist communities – how, for example, does Māui slow the sun and fish up Te Ika a Māui in a reality where all his movements are recorded and monitored by ubiquitous surveillance?5 It seems clear that those needing the most support in our society are the most likely to be targeted, because our systems are imbued with race, class and gender bias. The technologies that we increasingly apply to these systems can’t fix them by themselves because they are also a product of the world and of the human prejudice that exists within it. Machine learning and AI learn from and reflect the information that is available, where people of colour, migrants and low- paid workers are paired with negative associations.

After the raids of Operation 8 there was a strong response across art communities to raise awareness and funds to support impacted whānau. There were art exhibitions and auctions, even a compilation album made by supportive musicians called ‘Rise Up’. For me, exploring this kaupapa as an artist was quite different to the kind of direct action that stems from activism, where there are definite objectives and desired outcomes. If the kaupapa was a ball then an activist might have a clear direction they want to kick it, while an artist might want to deflate it and turn it inside out before putting it in a gallery.

Te Āhua o te Hau ki Te Papaioea is a surveillance vehicle that sits within a gallery space. The fi playing on the windscreen follows the van as it drives past each of the four houses raided in Palmerston North. It’s a bit like those old movies that show people ‘driving’ in a car while a screen behind them shows scenery passing, but in reverse – visitors are invited to sit inside and watch as the van navigates the road ahead. The surveillance van is calibrated to capture qualities of the ‘unseen heart’ referred to in the whakataukī earlier. These qualities are imagined as hau – an invisible aura that encompasses people and land. Hirini Moko Mead described hau as “wairua in the form of coloured rays coming off the body”.6 Te āhua o te hau is the aura, a “material form of the invisible hau” which encompasses personality and lingers after people have left.7 Encapsulated within the concept of hau are qualities such as mauri, mana and tapu – values that define and express individual and community relationships to life and the world. Mauri is a life force that Māori Marsden described as a “bonding element creating unity in diversity”.8 Tapu is an energy that surrounds people like a force field and which Katarina Mataira expressed as representing “sacred boundaries within which power is used for purposes of good virtue”.9 Mana is often described as a creative energy. Charles Royal said that “while mana is a creative entity in itself it does not encompass the negative aspects of the kind of power that leads to harm in society. This is why mana fosters relationships and community, whereas power does not necessarily foster relationships.”10

The first iteration of the van played a different film, gathering data as it drove through the streets of a small town. The graphics were based on the head-up displays we see in sci-fi films, where simulations mediate the interface between the viewer and their environment. As the journey progresses the volume of onscreen information increases until the contextual information from the landscape is obscured. Te Āhua o te Hau ki Te Papaioea is also a simulation but of elements that are intangible. I was conscious when making this work of the way explorations of surveillance tend to rely heavily on the visual, which was something I wanted to resist, when so much of our prejudice stems from how we physically present or are represented in the world. The outcome is a visual representation of a type of surveillance that involves ways of seeing while alluding to things unseen – a gaze reorientated from policing to one that imagines the interconnected relationships between mana, tapu, mauri and hau, attributes that reach beyond the corners of the whare.