Peter Robinson Cache (detail) 2011. Polystyrene, steel. Courtesy the artist and Sue Crockford Gallery, Auckland

De-Building

For many passers-by, Christchurch art Gallery is identified by its dramatic glass façade—the public face it presents to the world. but De-Building is an exhibition that offers a very different view. bringing together the work of fourteen artists from new Zealand and farther afield, this group exhibition draws inspiration from the working spaces gallery-goers seldom see: the workshops, loading bays and back corridors; the scruffy, half-defined zones.

What follows are closer looks at four works in the show, drawn from the De-Building handbook we've just published.

Instead of resting contentedly inside the Gallery, this art itches to go through and behind—to sand, cut and hammer away at the skin of the building and see what's uncovered in the process. along the way, it seizes the right to make creative misuse of whatever is lying around, from display cases, tools and screws to crates and packing materials. If the Gallery seems a little rattled or even offended by all this attention, that's only as it should be. any fascinated inquiry is going to generate some friction and tension along the way.

What follows are closer looks at four works in the show, drawn from the De-Building handbook we've just published.

Callum Morton

The crates in which expensive artworks travel are formidably well-built things. And the thing that they are built to do is keep the world out. Their security seals, vapour barriers and foil linings are all designed to repel any threat to the precious object within. But there are also plenty of stories about crates and shipping boxes that have trouble on the inside—crates whose interiors have been infiltrated by drugs, weapons, nasty insects, smuggled creatures and (in the worst of these stories) human cargo. The post 9/11 terrorist panic has combined with the fevered imaginings of Hollywood thrillers (snakes on a plane!) to turn crates into up-to-the-minute objects of anxiety. Forget about endangered artworks, this paranoid point-of-view suggests. That big box in the loading bay could be a threat to you.

In Callum Morton's colossal new sculpture, those two fears—the threat to art from outside the crate, and the threat to us from inside it—are spectacularly and noisily combined. What connects both threats in Morton's scenario is the fact they're more imagined than real. After all, a crate you can see inside is just a crate. A closed crate like Morton's, by contrast, is a mystery object, the start of a plot, a place for rumours and suspicions to germinate. And when the crate is big enough to park a small truck inside, our suspicions grow correspondingly grandiose. At once funny and fearful, Monument #24: Goodies turns the art gallery into a breeding box for anxiety—a place where mild and unthreatening things grow to tyrannical proportions, looming in the collective mind. Why's it so big? How did it come to be sitting in a room barely large enough to hold it? And why—this really is the unswervable question—does it shudder violently every few minutes and emit a very loud miaow? This is art-anxiety, supersized. Fear in a funhouse mirror.

Callum Morton Monument #24: Goodies 2011. Wood, pneumatic machinery, soundtrack, sound equipment. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne

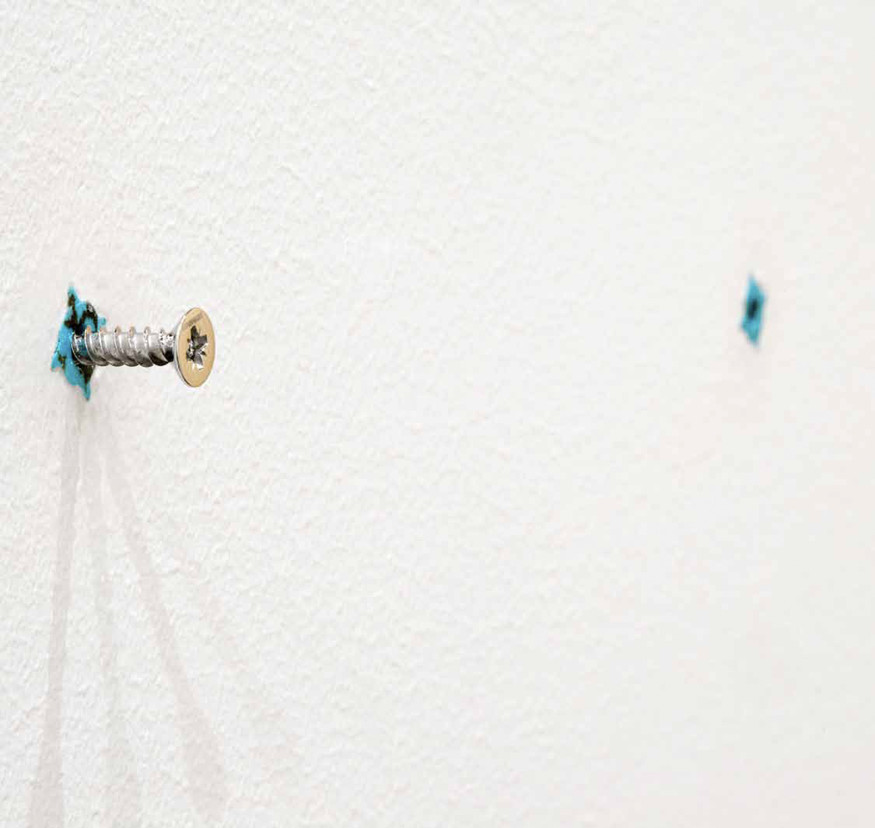

Susan Collis

Most gallery-goers will have a story of The Show They Just Missed—of trekking for miles across an unfamiliar city to see a wonderful exhibition, only to discover that it's just finished or hasn't yet started. The surest sign you've missed the main event is a row of screws on the wall—irrefutable evidence that the show is changing over and the art is somewhere offstage.

In the material world of Susan Collis, that kind of evidence should never be trusted. Since encountering her beautifully duplicitous sculptural variations on the lonely row of screws, I doubt I'll ever turn and leave a space where 'nothing' is on show without taking at least a quick second look. Collis's work As good as it gets consists of nothing more than three blue Rawlplugs and a single screw embedded in the gallery wall. Except that the screw is not really a screw at all but a meticulously crafted dupe, an undercover artwork fashioned from no less a substance than 18-carat white gold. The Rawlplugs are the product of an equally exotic bit of subterfuge, with turquoise doing its best imitation of hardware-store plastic. Ever since Marcel Duchamp came up with his 'readymade' artworks in the 1910s, artists have been granting value to mass-produced objects by relocating them in the gallery context, short-circuiting the old expectation that artists should handcraft their work. But when Collis handcrafts an object that pretends to be mass-produced, the outcome is more wayward and perverse. Screws after all are worker objects, so cheap they're bought by the sack-full. So is Collis honouring the role of these humble items by recreating them in luxury metals? Or is she demonstrating the arbitrariness of that value by concealing precious metal as mass-produced steel—performing an act of reverse alchemy in which gold is forced to come down in the world and lead a normal life? Whatever the answer, there's no missing Collis's larger point, which is all about attention. In this artwork, riches only come to those who look very close.

Susan Collis As good as it gets (detail) 2008/10. 18-carat white gold (hallmarked), white sapphire, turquoise, edition of 10. Courtesy the artist and seventeen, London

Fiona Connor

When Fiona Connor came to Christchurch Art Gallery in mid 2010, one of the first things she asked about was the row of windows on the building's south façade. It took me a moment to remember which she meant—and for good reason. Though the windows in question were designed to connect the exhibition spaces with the flow of life outside, they've been walled up internally ever since the Gallery opened. In that state, they bluntly bear out Brian O'Doherty's famous assertion about galleries obeying 'laws as rigorous as those for building a medieval church. The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off.'

Windows and what lies behind them were on Connor's mind for good reason. She was visiting the Gallery to look at a location for What you bring with you to work, her installation of facsimile domestic window frames that are inserted directly into gallery walls. The usual function of windows in a building is to let the outside in, admitting light and air into the dark interior. What makes Connor's work so memorable is the clarity with which it reverses this equation, effectively letting the inside out. The homely ordinariness of the windows is startling enough in the institutional setting, as if a home-building demo yard had suddenly commandeered the Gallery as a showroom. But the real shock and delight occurs when you step closer and find yourself peering into the working space behind the wall, the dusty landscape of the de-build.

By opening new windows inside a building, Connor provides a giddying sense of how thin and provisional that thing called a gallery really is—a matter of white paint and some hastily buttressed walls. Yet it would be wrong to characterise Connor's work solely as a back-of-house exposé or hard-headed 'intervention'. These are not anonymous openings, after all, but specific domestic windows. In fact, the look of each window is the product of Connor's collaboration with some very specific viewers—a group of gallery attendants whose bedroom windows she has faithfully duplicated. With this back-story in place, approaching each window becomes an even stranger and more intimate business, as if you're looking into someone else's space through someone else's eyes. In addition to all the materials she reveals behind the scenes (sawdust, four-by-twos, paper), what Connor brings into play here are the 'immaterials' of gallery life—the thoughts, memories, imaginings and dreamlife of those who walk through and mind the exhibition.

Fiona Connor What you bring with you to work (detail) 2010. Window frames, glass, timber, fittings, wax, paint, 7 windows exhibited from a group of 9. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2010

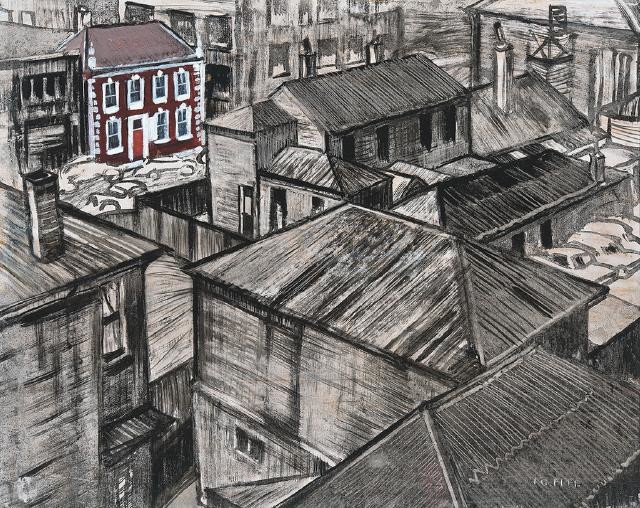

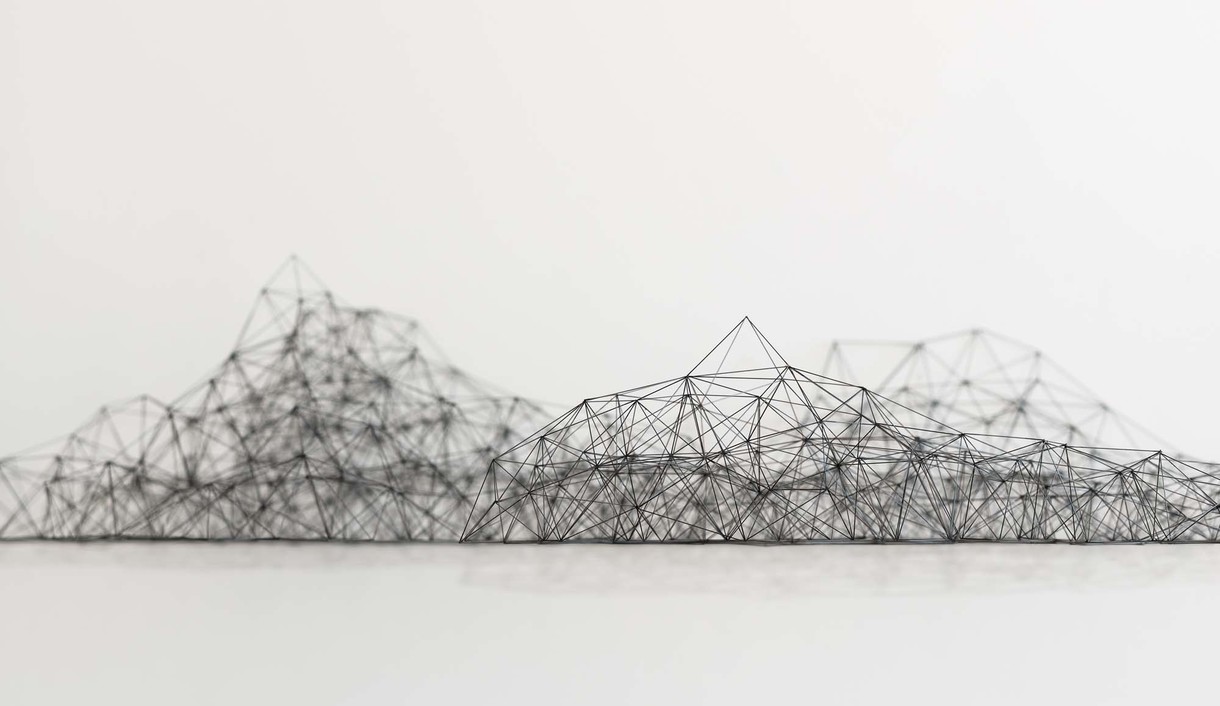

Peter Robinson

For many viewers, I suspect the most 'live' and memorably unstable work in De-Building will be Peter Robinson's installation—memorable precisely because it leaves viewers unsure of both the art's physical safety and their own.

Consisting of approximately 100 cubic metres of polystyrene and over 300 metres of steel reinforcing rod, and completed only days before opening after a week of in situ experimentation, Cache is the latest and most spectacular of Robinson's meditations on the strange objects that galleries employ to protect works of art. The curious origin of this obsession was a trip Robinson took in the early 2000s to London's Tate Modern, where he saw Robert Morris's famous mirror box sculpture of 1965/71 fenced in by protective stanchions. Not only was the experience of the work, in Robinson's words, 'completely destroyed by the very device that was meant to protect it', he also found himself seized by anxiety that visitors would trip on the stanchions and thus do double damage—to the art and to themselves.

In a series of installations since then, Robinson has pushed this brand of institutional overprotectiveness into overdrive, creating worlds in which there is no longer any telling the protective devices from the things they protect. While much has been said about Robinson's spectacular deployment of that familiar packaging material, polystyrene, his De-Building installation marks the fullforce arrival of a new preoccupation with steel reinforcing rod. Bent into abstract snarls and tangles, angling across the floor, rising up four metres and more in the form of shelves or two-footed 'super stanchions', mutely blocking our paths or threatening to snag us as we squeeze past, and generally filling the room with a kind of vibrant three-dimensional drawing, Robinson's new steelwork calls to mind a dizzying range of art historical precedents, from Picasso and Julio González through to Anthony Caro and Jesús Rafael Soto. But in its teetering height and jungle-gym profusion, and its constant combination with slabs and rocky lumps of polystyrene, what it calls to mind most forcefully is the look of half-completed buildings, where rusty steel rod protrudes in every direction from freshly laid concrete. Where the role of this steel in the construction industry is to hold buildings together, Robinson uses it here to opposite effect—creating a portrait of the gallery as a profoundly unstable place. A place where we need to watch our step. A de-building site.

Peter Robinson Cache (detail) 2011. polystyrene, steel. Courtesy the artist and sue Crockford Gallery, Auckland