Shifting Lines

Andrew Beck Unison (11.45am, 5 November) 2013. Oil paint, sunlight. Courtesy of the artist and Hamish McKay Gallery

It's where we live: the encrusted surface of a molten planet, rotating on its own axis, circling round the star that gives our daylight. Geographically, it's a mapped-out city at the edge of a plain, bordered by sea and rising, broken geological features. Zooming in further, it's a neighbourhood, a street, a shelter – all things existing at first as outlines, drawings, plans. And it's a body: portable abode of mind, spirit, psyche (however we choose to view these things); the breathing physical location of unique identity and passage.

This show is about drawing, as an idea and as a means of connecting us to different kinds of places. In doing so, it brings together the work of six artists – Andrew Beck, Peter Trevelyan, Katie Thomas, Pip Culbert, Gabriella Mangano and Silvana Mangano – all of whom use line to investigate space and structure in unexpected ways. The claim that their work might help redefine how we view drawing here seems reasonable. From tracing and rubbing, cutting and subtracting, measuring and ruling; to video performance and construction with delicate pencil leads, drawing as an idea is allowed to take very different forms.

The grouping conveys a sense of spacious minimalism; for some, perhaps, the thought that there's not much in it. A slowed down reading, however, allows each work to be recognised as a distinctive balancing act of simplicity and contemplative complexity. Each disrupts physical space with line, and deftly deals with imagined or symbolic space. Visual connections and metaphorical associations unfold into broader ideas, ranging from the planetary, geological or geographical to the personal, bodily or psychological. The artists' varied tactics show them to be engaged, agile and skilfully adept.

In Planetary Space

Auckland-based Andrew Beck is a 2010 MFA graduate from Massey University School of Fine Arts, Wellington who is already building an impressive local and international exhibiting record. In his investigations into the nature of matter and light, he acknowledges the influence of artists such as Nancy Holt, Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, Robert Irwin, James Turrell and Lee Ufan. His theoretical underpinnings range from classical philosophy (he cites, for example, Parmenides' theories and understanding of change) to Isaac Newton's understanding of inertia, and 'the Māori proposition of Te Korekore', an esoteric realm of potential being.1

From this framework, Beck has created for this show a striking, rigorously minimal work. At the time noted in the title, Unison (11.45am, 5 November) existed as an angular, hard-edged shape marked out in black oil paint in a window corner, falling at an angle from the place it began, an architectural segment of sunlight. Continuing in a band around a projecting column, it angled down again on a different plane, ending at the shadow's edge, neatly joining two portions of light. With each global rotation and within a few days, the alignment became increasingly inaccurate – if given one year's wall space, it would briefly realign. Located somewhere between drawing, painting and installation, this temporary intervention existed most plainly within a recurring moment of passing light. In pinpointing a moment and location in the universe – and in matching our preference for bringing the unfathomable to a scale we can deal with – it also proves the artist's position that time and space are materials to work with.

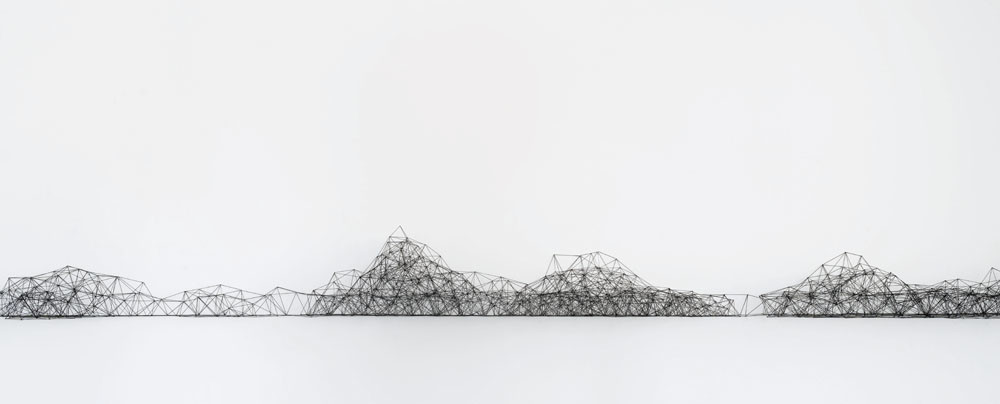

Peter Trevelyan survey #4 2013. 0.5mm mechanical pencil leads. Courtesy of the artist

Mapping Out

Wellington-based Peter Trevelyan's survey #4 (2013) is a quietly mind-boggling three-dimensional drawing that more obviously claims the territory of sculpture. At around four metres long, an elongated, wall-based structure constructed of 0.5mm mechanical pencil leads, it is a feat of originality and exquisite engineering precision. While the whole construction retains the detailed sharpness of its chosen medium – and much of its fragility – the interconnecting trigonometric systems that form its internal workings make it relatively robust. The work is airy and light, but within its interlocking geometry, fine darker points are formed in concentration where multiple lines converge.

Viewed from a distance, its spread out form suggests topography, hills outlined from far away, as seen from shipboard by late-eighteenth or early-nineteenth-century European explorers. While alluding to mapping or surveying for future reference, Trevelyan's investigation is also evidently about testing and proving provisional structures, an aspect aligning it to drawing's traditionally understood role. Part of a growing body of work, survey #4 displays Trevelyan's pleasure in seeing drawing being made to exist in a literal, three-dimensional sense, and his interest in setting up layered propositions. Whether tiny or vast, his spatial drawings can seem impossibilities, and in existing at all neatly knock the stuffing out of complacency or boredom.

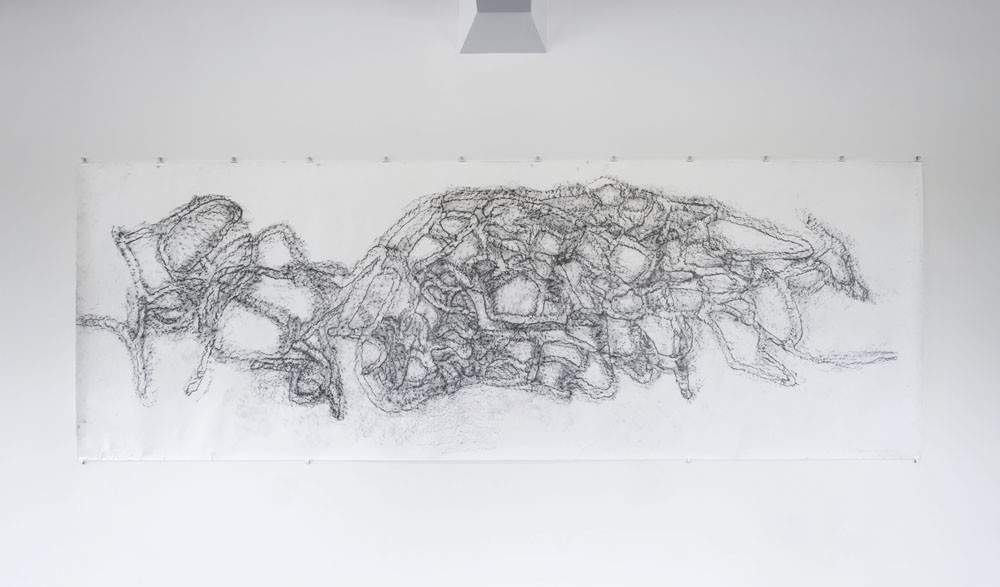

Katie Thomas Westenra Terrace 2011. Graphite rubbing on paper. Courtesy of the artist

Zooming In

Graphite, topography and a sense of risk come together in different ways in Katie Thomas's 4.25 metre drawing Westenra Terrace (2011), a frottage rubbing from the surface of a road on the Cashmere hills. Thomas was at the Christchurch Arts Centre on 22 February 2011, hanging a solo exhibition just as everything shook, meaning that her MFA Painting (School of Fine Arts, University of Canterbury) show was a bit delayed. In the time that followed, her attention was drawn to the clusters and patterns of lines starting to appear on city roads: temporary repairs to cracks, intended to keep out water and to prevent further damage. Thomas's interest in the amorphous 'found drawings' resulted in several large-scale rubbings (with assistance during the process from thoughtful locals sailing in with protective orange cones).

These are less about a historical moment or posterity, however, than they are aligned to the surrealist impulse of collecting imagery connected to an evolving and established painting practise. As Max Ernst used the frottage technique from 1925 as a starting point for more elaborate painted or collaged compositions, Thomas has viewed the large drawings as reference material; plus-sized notebook diagrams connecting to and feeding into her painting. With its smudged hand-marks, fine road texture and abraded directional lines, this drawing holds completion as an entity, and with its organic, macro/micro structure links strongly to her recent canvases. Despite being unorthodox, even extreme, it may in this sense be the most traditional type of drawing in this show.

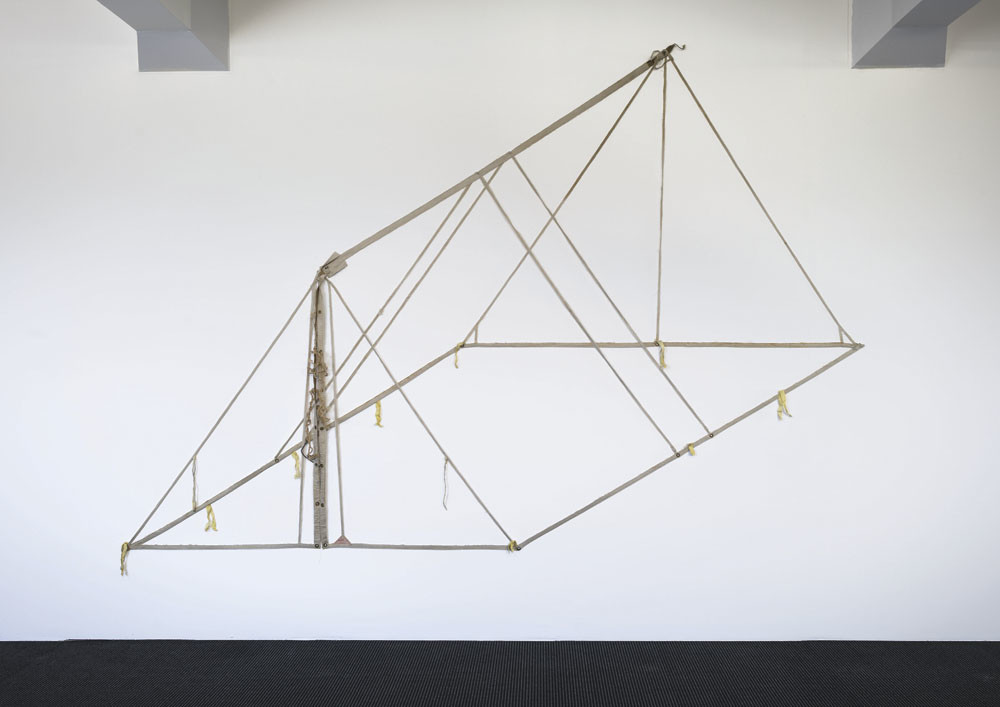

Pip Culbert Pup Tent 1999. Canvas, metal, rope. Courtesy of the artist

Finding Shelter

Drawing is further redefined by Pip Culbert, a British artist based in France with whom (I hope it's alright to say) we feel something of a family connection.2 Culbert graduated from the Royal College of Art in London in the early 1960s, her specialities then being industrial design and engineering. She began exhibiting her fabric-based works in 1985 and first showed in New Zealand in 1993.3 Pup Tent (1999) belongs to a significant body of work that began in found objects constructed in cloth (her inventory also includes shirts, tarpaulins, flags, pockets, surf sails, trousers, quilts, ties, bags, ironing boards, upholstery, parachutes, aprons and handkerchiefs). Culbert's technique involves cutting away to remove everything but the bones – the essential, strengthened lines of stitching. Drawing in effect by subtraction, this is also drawing in the sense that it renders three-dimensional objects two-dimensional. Pinned to the wall, her diagrammatic tent projects like an isometric plan, denied perspective but retaining a spatial sense.

As with all of her reductive cutaways, Pup Tent holds divergent metaphors; the tent in its temporality is a very old metaphor for the body. Like one of Plato's ideal forms, it also speaks here of structure, shelter and support. In a city that has been shaken back to its pioneering roots, awaiting new structures again on almost every street, for me its A-frame form recalls the well-known 1864 photograph by early Canterbury Association settler A.C. Barker, as well as paintings in the Gallery and Canterbury Museum collections featuring tents by artists including William Holman Hunt, William Fox, James Edward Fitzgerald and Austen Deans. (That I mention these is possibly due to an odd fact: with the city's public art collection presently safely locked away, Culbert's 1999 work might now be one of the most historical works of art currently on public display.)

Gabriella Mangano and Silvana Mangano Rewind 2012. Single channel high definition digital video 16:9, black and white, 4 minutes. Courtesy of the artists and Anna Schwartz Gallery

Body Work

Through performance, video and sound, Melbourne-based Gabriella Mangano and Silvana Mangano bring a particular kind of symbiotic relationship and understanding to their art, having worked collaboratively since 2001 (they completed BFAs in drawing at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne in 2001 and 2003 respectively). They have featured regularly in their videos – sometimes drawing, choreographically and simultaneously – and maintain strong links in their work to ideas around drawing.

The digital video Rewind (2012) feature shows a solo performer and her shadow, and is structured around the body's movement, rhythm (including through a quietly pulsing soundtrack) and changing compositional balance. With balletic poise, she manoeuvres a rectangular black shape, carefully held at each end, which moves and divides the screen, sometimes disappearing out of frame. With face concealed, the performer appears to respond to her shadow as well as her own ghosted image, which is simultaneously screened. The camera zooms slowly in and out; movement changes pace to the changing tempo of a digital heartbeat. The black shape is the dominant form and a kind of riddle: what is this thing that the artist carries and treasures? Is it changing identity and self-definition, a capital 'I'? A stand-in for the other? Or simply a formal graphic device? It is fine to stay guessing. As with each of the artists' works shown here together, it will nonetheless have me trying to figure it all out.

Ken Hall

Curator

Shifting Lines is on display at 209 Tuam Street until 19 January 2014.

NOTES

-------

1. Te Korekore was defined as 'the realm between non-being and being: that is the realm of potential being' by Māori Marsden, quoted in Te Ara http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/te-ao-marama-the-natural-world/page-3

2. Pip Culbert is married to Bill Culbert, who recently represented New Zealand at the Venice Biennale, in Front Door Out Back, curated by Justin Paton.

3. She has also shown her unique brand of minimalism in solo and group shows in UK, France, Australia, Japan, Germany and the US.