Tim J. Veling Latimer Square, Christchurch, 2012, from Adaptation, 2011–2012. Digital C-type print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the artist 2012

City of Shadows and Stories

Tom Goulter considers communal foolishness in the history of Christchurch.

If cities are the ground into which we plant stories, the soil of Ōtautahi – later Christchurch – is undergoing a protracted tilling season. Five years is a long unsettlement in human terms; on a geological (or indeed narratological) scale, time moves more gradually. Christchurch exists today as a rich aggregation of narratives, propping up physical edifices of crumbling stone and cardboard.

Few cities were as rigidly planned and executed as the Christchurch of old. Four avenues – Bealey, Fitzgerald, Moorhouse and Deans – framed the central city, pinned in its centre by a cathedral spire. The latter’s shadow fell on a square whose soil once embraced dead from Puari Pā, whose cobbles would one day be trod by wizards.

Ōtākaro, the Avon River, ran through the city from northeast to southwest, a complementary winding line was formed by the grid’s diagonal overlays, Victoria and High streets, and the two grassed squares, Cranmer and Latimer. The box was then bisected horizontally by Worcester and vertically by Colombo, the creaking spine of the whole edifice.

Worcester. Gloucester. Avon. Beckenham. New Brighton. All pointers toward a desire to make an England more English than England herself. An ideal England, where long shadows still fall on John Major’s ‘cricket grounds [… and] invincible green suburbs’.1

The result was some theme-park version of Englishness: a place where the Jesters could be seen at the Court Theatre and the Bard hosted drinks by the Avon; where students told Canterbury tales and Manchester was the place for entertainment of negotiable virtue.

But equally, it’s long been a place that divides into harsh absolutes, splitting its culture into deep binaries. Freaks and normals, gang patches and skinhead leather, saturnine old boys and jovial youth.

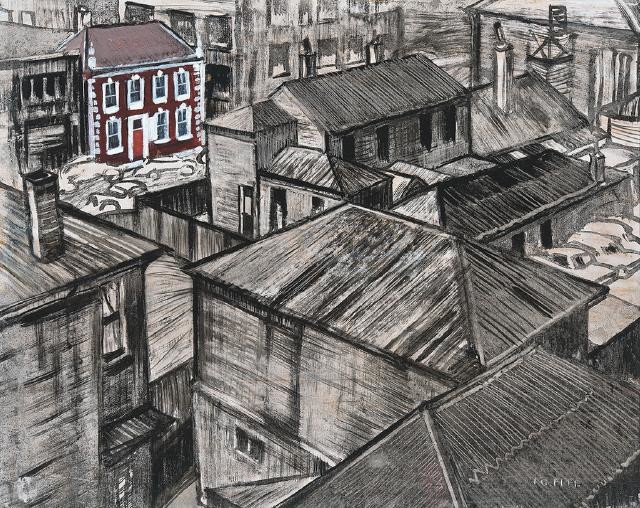

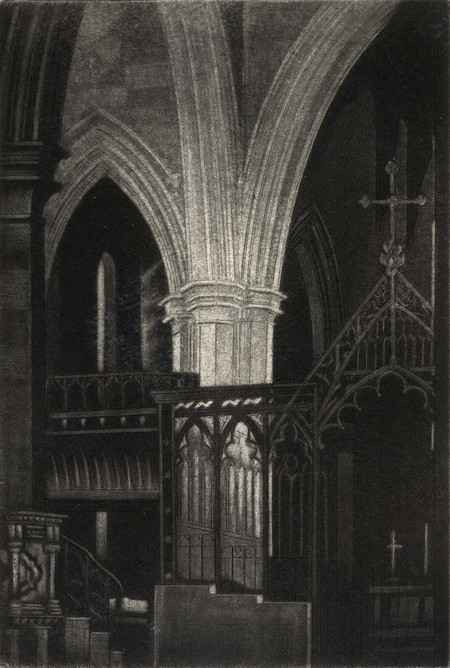

James Fitzgerald The Lighted Pillar 1925. Etching and aquatint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2001

The Christchurch sewerage system is one of the world’s flattest, meaning that pushing shit from A to B is an uncommonly difficult task. Perhaps it was this difficulty that led, in the years leading up to the quakes, to the trouble with the oxidation ponds in the city’s estuary – where the treated sewage is left after we’re done with it.

Leave treated sewage in a shallow wetland, and if the wetland goes dry in a hot summer – well, what can you do? You can’t fight the sun. And if a northerly scrapes like sandpaper over those crud-caked pond-beds and whips clouds of sun-dried night-soil into a drifting cloud of airborne excreta, what are you going to do? Rich complexity of the ecosystem. You’re breathing shit. And then when the shit falls on the seawater and flows back to the shore, it washes up on the beach at Sumner by Cave Rock – known to Māori as Tuawera, which means ‘cut down as if by fire’. It settles on the tideline like the great black whale that gave the rock its name. Tūrakipō, a local chief, had put a death curse on a woman he couldn’t have, so the girl’s father climbed the hill above Tūrakipō’s beach and sang karakia that rolled down the hill and out to sea. The hymns of nemesis brought forth a whale, which beached on the shore. Tūrakipō’s men feasted on the whale, and caught a sleeping sickness from which they never awoke – cut down as if by fire.2

Christchurch’s residents may prefer a thing to be simply accessible, directly before them, but let it not be said that they are without a yearning for meaning. So it was that Arthur Worthington – Counsellor Worthington MD, until questions were asked – could drift into town from Parts Unknown, USA, and speak with an exotic accent about ‘substance’ and ‘matter’ and ‘forms’ and ‘ideals’ and become recognised, not as a kook, but as a prophet of ultimate truth.

A sermon transcribed for the ages began with Worthington taking the stage beside a table bearing a burning lamp. ‘Brethren,’ he told his congregants, ‘you think you see a lamp before me on the table. You think that lamp is an actual, concrete, permanent lamp. You are wrong. The only actual, real, and eternal thing is the concept of that lamp in your minds and mine.’3

Worthington elaborated on this theme, holding forth on Platonic idealism and Berkeleyan immaterialism, before knocking the flame onto the ground – crying triumphantly that the lamp was merely symbolic of the concept of a lamp and had no actual existence of its own. The crowd, thrilled by the realisation that they had not been burned to death, applauded and spread the word of Worthington’s transcendentally sensible philosophy.

It wasn’t long before Worthington had gathered enough capital from followers to erect, at Latimer Square’s northern end, a Temple of Truth from which to preach. Worthington’s flock constructed for him a lavish townhouse alongside the Temple, where later sat one of Christchurch’s longest-running hostels – now a car park.4

By the time Christchurch’s preachers, their congregations dwindling, looked into allegations of impropriety between the Prophet of Truth and his female-only Society of the Blue Veil, the lamp had been smashed and the flame extinguished. And once anyone inspected the construction of the Temple, whose Solomonic pillars and biblical-classical architecture masked a cheap wooden frontage painted to look like stone with sprayed-on sand, Worthington had left town as mysteriously as he appeared. He left behind him an out-of-pocket parish blinking in the sunlight of a world that now seemed but a figment – the signpost to an unreachable higher reality, populated by fickle confidence tricksters.

Arthur Worthington’s lusty depredations may have been bad magic or just good honest confidence trickery, but through ringing word and hidden deed, he taught his parishioners that the line between the two is thinner than we think. This, in itself, is not so dark a spell to cast.

The same can’t be said of the gatherings over the river from the Temple of Truth at the Barbadoes Street Cemetery. Here were held moonlit black masses – red wine and clove cigarettes – at the grave of Margaret Burke. The grave was said to display bloody handprints, and the city’s amateur necromancers would gather in the hope of contacting the hosts of the underworld. Their calls were answered by crystals of iron pyrites, slowly oxidising blood-red within the stone, but in 1929 The Press ruled that for graveside visitors from as far off as the USA, the macabre marker’s story was ‘too good to spoil by rationalising explanations’.5

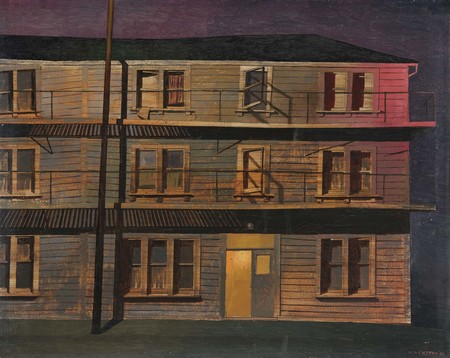

W.A. Sutton Private lodgings 1954. Oil on canvas on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1959

Margaret Burke had come from Ireland to become a kitchen-hand in the Cambridge Terrace house of wool-man William ‘Ready Money’ Robinson. In 1867 Robinson had travelled to Latin America and brought back from Panama a manservant named Simon Cedeno, whom literature identifies for us as slight, handsome, around twenty-eight years of age, ‘of negro extraction’ and ‘in all respects a superior member of his race’.6 Otherness marked his time in Christchurch. Cedeno would later testify to the racial harassment which Ready Money apparently considered a condition of employment.

In January 1871, officers were called to the Robinson house, where Margaret Burke and another servant had been stabbed by Cedeno. The first man on the scene had to pry Cedeno’s hands from around Burke’s neck. ‘You’ll kill her, you brute!’ the officer said he told Cedeno; to which Cedeno reportedly answered, ‘Yes, I kill.’

The money-line of the case comes when Cedeno is being cuffed and being removed from the premises. ‘You kill cows and Māoris’, he is quoted as telling arresting officers. ‘For my part, I kill English girls. People call me wildman, madman, but I am not.’

Writing up the case in the 1930s for New Zealand Railways Magazine, Charles Treadwell strongly suggested that Cedeno’s colour and accent biased the jury from the start, adding that an insanity plea would have saved him in a modern court. Treadwell and crime writer Dudley Dyne take pains to put Cedeno’s more salacious lines in the mouths of unreliable witnesses.

Simon Cedeno’s body hung from the Lyttelton gallows before joining Margaret Burke’s at Barbadoes Street, where the two immigrants lie beneath the ash and broken glass.

‘As a nation’, wrote Robin Hyde in response to the Worthington affair, ‘we seem to be too repressed, and consequently seize on almost any pretext for making communal fools of ourselves.’7 We leave our shit in shallow pools. We curse the sun for shining and the wind for blowing, and we are ourselves cursed for eating the wrong meat. We spray a wall with sand and call it stone and wait for bloody handprints to appear, and we don’t know whether this is magic or a stubborn insistence on things being the way they aren’t. We don’t know objects from the ideas they represent, or the other way around. It’s only because we know so very much about the way of things that we are so surprised when they turn out not to be that way at all.

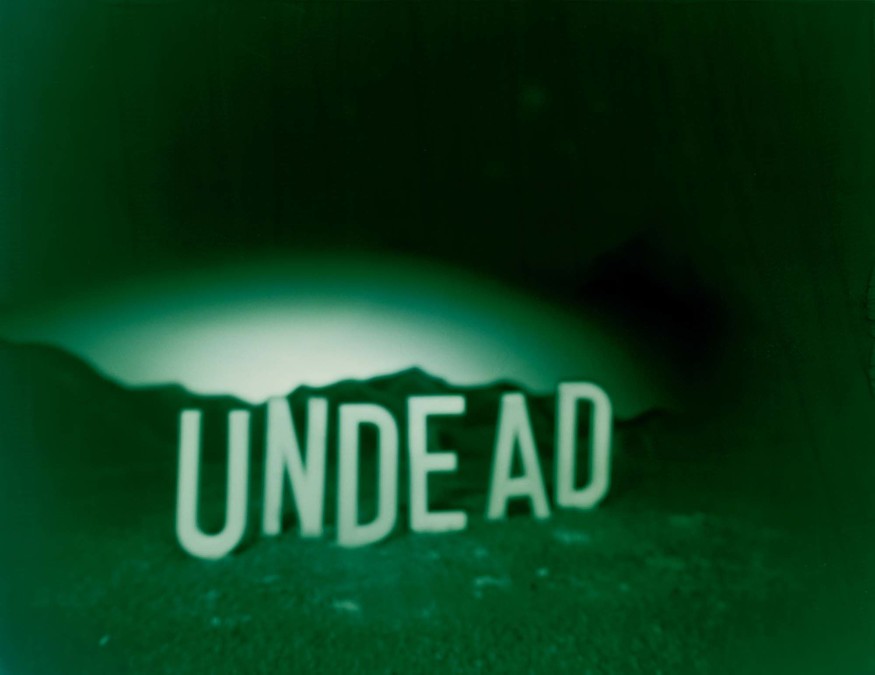

Ronnie van Hout Undead (Green Version) 1994. Photograph. COllection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased, 1995. Reproduced with permission

David Cook Cathedral Square 1983. Photograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1987

When much of Christchurch fell in February 2011, a visibly disturbed Prime Minister Key summoned a gift often overlooked by his detractors: the natural hierophant’s ability to craft instructive stories out of subjective feelings. To speak – often disarmingly frankly – less of what just happened than how to feel about it. He spoke of the city’s ‘aching hearts’ and ‘great spirit’ in battle with raw nature in her ‘violent and ruthless’ aspect.8

His words felt true; this is Key’s talent. Brethren, look to the lamp. Key will often begin by observing just what New Zealanders are seeing (‘yeah, well, I think if you look…’), following causatively to suggest how we might then feel about it. And if we recognise the feelings described, it follows that we’ll accept our place within the narrative in which Key situates those feelings. For a people as famously reticent as New Zealanders – or at least the New Zealanders of Key’s stalwart base – his confessions of feeling are powerful tokens.

But to personify a location like this is as tempting as it is impossible. Regardless of how we look at it, Christchurch only exists because we say it does. The place itself, tight shingle and steadfast rock, doesn’t think of itself as Christchurch or as Ōtautahi or as anyone’s home. The earth didn’t shake because of anything we did upon its surface – it moved because that’s just what the earth does. Not to spite us, but in spite of us.

Druidic architects once stirred human blood into their foundational cement. More recent builders laid Bibles or effigies of human significance into the cornerstones of their constructions. Reminders of a universal principle of building, that when we lay down foundations – whether for a shack, highrise or city itself – we extend our own human meaning down into the earth, idea and narrative mixing awkwardly with clay and loam.

It had been easy enough to incorporate September 2010’s pre-dawn shiverings into the Christchurch narrative. Seismic trembles rocketed up through the strata even as primal sparks rang out through sleeping brains, touching off reptilian fight-or-flight synapse patterns. We rushed to make sense of the event, to fit it into a narrative. Tight faux-English grid and village-green suburbs tested by Antipodean ring-of-fire wildness. Earth’s fury. Why didn’t ‘They’ warn us? City and story alike were cracked but repairable. Look back or move forward? Either seemed feasible.

But after February the following year, it was clear the graft had never taken. Blood and Bible alike sit dead in the soil, neither swallowed nor spat back. The land doesn’t want to reject or revise our story. It simply doesn’t care. No longer can we feel we’ve sunken our awareness of place and community into the earth. The only place Christchurch truly exists, it’s become clear, is in its people. We might all agree upon what Christchurch is or isn’t. If nothing else, we all agree that it’s there. But there’s one party that reserves judgement on even that most basic fact, and that’s the location itself.

The earth doesn’t move out of malice or ruthlessness. The earth simply moves. Any attempts to ascribe human meaning would be like trying to read a buried Bible. Like Tūrakipō and the whale, Worthington and the lamp. We’re left with a place made out of narratives and experiences, streets forever trod by those who’ll never tell their stories.

Tom Goulter was born in the Canterbury town of Lincoln and raised in the Port Hills of Christchurch. He wrote an early draft of this article in an office that was crushed by falling boulders in February 2011. He holds a master’s degree in creative writing from Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters and writes about literature and local culture for Wellington’s FishHead magazine.