B.

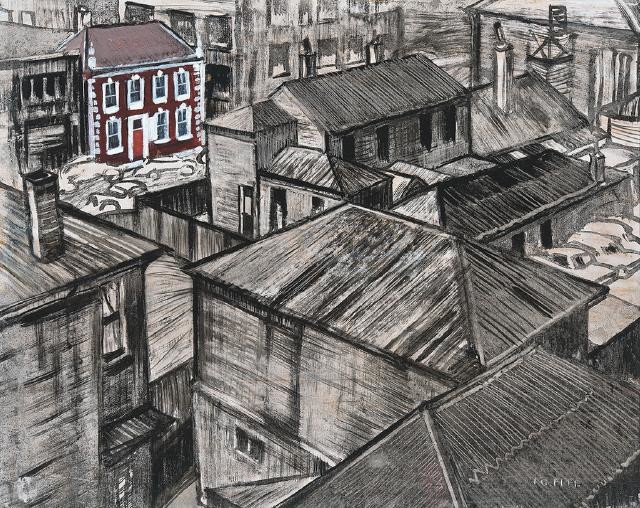

Louise Henderson, Addington Workshops

Behind the scenes

For many years, the piercing whistle of the railway workshops off Blenheim Road was Addington's alarm clock.

At 8am, a great battalion of working men biked in through the Clarence or the Lowe Street gates: at 4.30pm, the gates opened and they cycled home again across the city. At its height, this heavy industrial complex employed more than 1000 people, and built locomotives, wagons, and carriages for New Zealand Railways as well as steel girders for bridges. When Christchurch artist Louise Henderson painted the workshops in 1930, they had recently been overhauled and expanded as part of a nationwide initiative to modernise the railways.

Louise Henderson arrived in Christchurch in 1925. A Parisienne, she met her future husband Hubert Henderson, a New Zealander, at the Louvre. Shortly after they were engaged Hubert returned to take up a position as head of mathematics at Christchurch Boys' High School: Louise went through a proxy marriage at the Embassy in Paris and sailed off to join him in Christchurch, where they lived for many years on Papanui Road (the house is still standing). "Arriving in New Zealand," she later commented, "was like opening a door for me. I discovered things I never knew existed. It was a new world."

Born Louise Etienette Sidonie Sauze in 1902, Henderson grew up in a cultured environment. Her grandfather had been an academic painter who became under-secretary to the French Minister of Culture: her father, Daniel Sauze, was secretary to the French sculptor Rodin. As a child, Henderson played with marble chips from Rodin's studio. As a young woman she studied at the School of Industrial Arts in Paris and then worked as a designer of embroidery and interiors for the weekly journal Madame. A year after arriving in Christchurch ("A cultured place, dull but sound", as she noted), Henderson was employed to teach design and embroidery at Canterbury College School of Art. Her students knew her as 'Madame': she represented a direct link for them with one of the world's centres of art.

What did the railway workers at Addington make of the stylish Frenchwoman in the beret who stood sketching them amid the noise and grease of the machine shop? There is not a great tradition of social realism in New Zealand art. Henderson's painting is among a handful of significant paintings depicting New Zealand workers and industry from the interwar years, including Christopher Perkins's Silverstream Brickworks (1930) and Rita Angus's Gas Works (1933). Henderson depicts the workshop as a bright, clean, industrious place: men stand at their lathes and machines, engrossed in their work. In the foreground two men examine a blueprint; another worker glides above the scene in a bucket attached to a gantry crane.

Like Perkins, and Angus, with whom she was close friends, Henderson has simplified and flattened forms and washed the composition with a clear and even light. The emphasis is on the geometric design afforded by the scene, where straight lines are painted with the aid of a ruler and incidental details are left out. This distinctive style, associated with the Canterbury School of the 1930s, nods both towards international modernism and to contemporary commercial art.

As road freight overtook rail, the Addington Workshops declined until they were finally closed in 1990 and gradually demolished. But sixty years earlier, when Henderson painted them, the workshops were not just a major employer in the city – they represented a distinct culture of their own, fielding choirs and sports teams and holding gigantic annual picnics to which workers' families were invited. The long-demolished shed in which Henderson sketched the men at work stood adjacent to the site of the current railway station at Addington and behind the heritage water tower. All that's left of the workshops today is the water tower, built in concrete and steel in 1883, which now stands isolated in the car park at Tower Junction.

This article first appeared in The Press, 14 October 2014.