B.

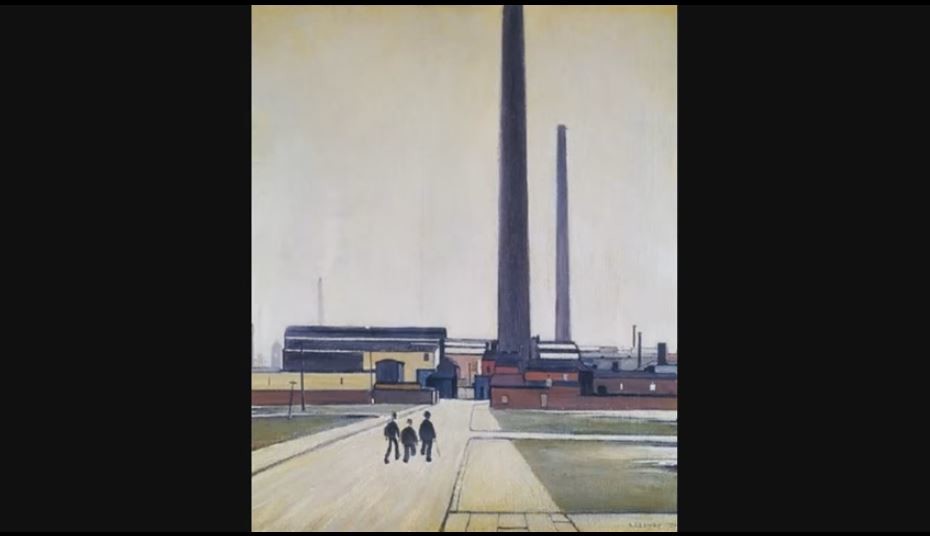

Factory at Widnes by L.S. Lowry

Collection

This article first appeared in The Press on 13 October 2004

Laurence Stephen Lowry painted Factory at Widnes in 1956, at which time he was Britain's most famous living painter. Lowry's fame increased in that year as he became the subject of a BBC television documentary, though his work had already been popular in British homes and schools as reproductions since the end of the war. If appreciation for his individualistic painting style was widespread, there was also fascination with L.S. Lowry the artist, who had projected in the press the image of a lonely recluse.

Though Lowry was less reclusive than his public persona, such an image was not without basis. A gangling figure with strong features and thick, cropped silvering hair, always dressed as if ready for the office, Lowry was a teetotaller who never married, and never owned a car, a television or telephone. In his brick house in Mottram-in-Longdendale near Manchester he surrounded himself with clocks, all set at different times. He was also intensely private, and throughout his life studiously kept friends unaware of each other.

A greater fiction he maintained was that he had never worked at anything but his art, while in fact he had been in paid employment since his teens, having retired in 1952 on full pension after 42 years with the same company - as a rent collector and clerk. Sensitive to opinions that might regard him as anything but a serious painter, Lowry guarded jealously his slowly-wrought success. It was not until his death that the public learned of the artist's unique industrial vision having been developed as he traversed Manchester on foot as a rent collector, committing wry and sundry observations to notebook or memory before their working into paintings in evenings and on weekends.

As with Lowry himself, Factory at Widnes seems intended to remain enigmatic. Wrought with great confidence and painterly skill, its formal qualities are tight and flawless. It is a carefully constructed image of balance and restraint. Anchored by strong horizontals and verticals - black chimneys surrounded by white industrial haze - the painting's focal point by the distant factory gates is strengthened by selective use of concentrated colour. Three comic bowler-hatted figures head nonchalantly towards the imposing distant towers and factory, suggesting an unfolding yet oddly impenetrable story that almost certainly reflects Lowry's characteristic impish sense of humour.

The iconography of this work is typical of the artist, with elongated industrial chimneys and human figures who are almost shorthand notations, dwarfed and somewhat dislocated by their surrounds. While L. S. Lowry is known best for his expansive vistas with multiple towering chimneys and crowds moving in rhythmic patterns, Factory at Widnes is a more sparse and elegant composition, in its formality surprisingly reminiscent of work by Lowry's modernist contemporary Ben Nicholson - though London art world manners and sophistication are completely absent here.

Lowry's view of the absurdity of human nature was a key inspiration. Those who knew him recorded his fascination with accidents for the people they attracted, patterns they formed, and the atmosphere of tension. Lowry had an individual turn of mind that found cripples comic, and managed his painted world - with its images of human oddity and suffering - like a Greek god or a puppet master, without sentiment.

Widnes, the setting for this particular miniature drama, is located on the Mersey between Liverpool and Manchester, and is a place where apart from major industry, little else worthy of mention has ever happened. An early postcard of the town shows a mass of chimneys pouring heavy clouds of dark grey (and the droll legend ‘With Compliments from the Smoke'). The birthplace of the giant ICI chemical company, Widnes in the 1850s had 6,500 people working in the chemical factories alone. For every ton of soda produced, there were two tons of alkali waste, leading eventually to the burial of the local ancient Widnes and Ditton marshes, and the description of the town in 1888 as "the dirtiest, ugliest town in England". When Lowry painted this work in the 1950s, 45 major factories still existed there - today its principal attraction is a museum of the chemical industry.

One of Lowry's friends, gallery owner Tilly Marshall, recalled recently the painter's particular feelings for Widnes, in that ‘he did think of the town as a place where nothing happened ... I do remember it was quite often used jokingly when we were not to be doing anything exciting in an afternoon. "Are you doing anything this afternoon Mr Lowry?" "Ooh I might go to Widnes Mrs Marshall" he would reply.'

It is tempting to believe Lowry also knew Widnes as one of those places where anyone famous who has ever been there becomes thenceforth mentioned in connection with it forever. One such person, whose visit is still recalled, was (a very young) Charlie Chaplin, who performed at Widnes' Alexandra Theatre before he hit the big time. Another who played there was Stan Laurel, before heading for America and meeting up with Oliver Hardy. For Lowry, whose own humour was irreverent and slapstick, and who had a known affection for Chaplin's art, the possibility that he could be mischievous enough to allude to these well-known comics in his work is real. Though somewhat on the wane, all three in the 1950s were still in the British public eye, with Chaplin having been exiled from America in 1952 for his political views, and Laurel and Hardy having made three recent British tours.

Having developed his work outside the fashionable circles of artistic critical debate, Lowry was comfortable in placing himself within the world of popular culture, a position from which he was almost certain to offend refined aesthetic taste. The contrast at this time between L. S. Lowry and the leading names of the London art crowd (Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson) is great. Lowry is fascinating for his ability to live and work by his own dictates. A long-term result, however, is that even today, many art critics and historians have difficulty knowing exactly where to place him.

As with the best humorists, and with the best of Lowry's paintings, serious notes are being sounded here. Far more than a highly-aesthetic jibe at Widnes for its tedium, the painting seems also a wistful reflection on popularity and impermanence, of passing humanity in a man-made, constructed world. "Will it last?" was one of Lowry's regular catchphrases, as part of a recurring fixation with the long-term value of his work. For me, this carefully considered work is one of Lowry's most beautiful and interesting. Admiration is only strengthened by an appreciation of its and the artist's enigmas, so the verdict on his question from this quarter is a resounding yes.

Ken Hall