Above Ground

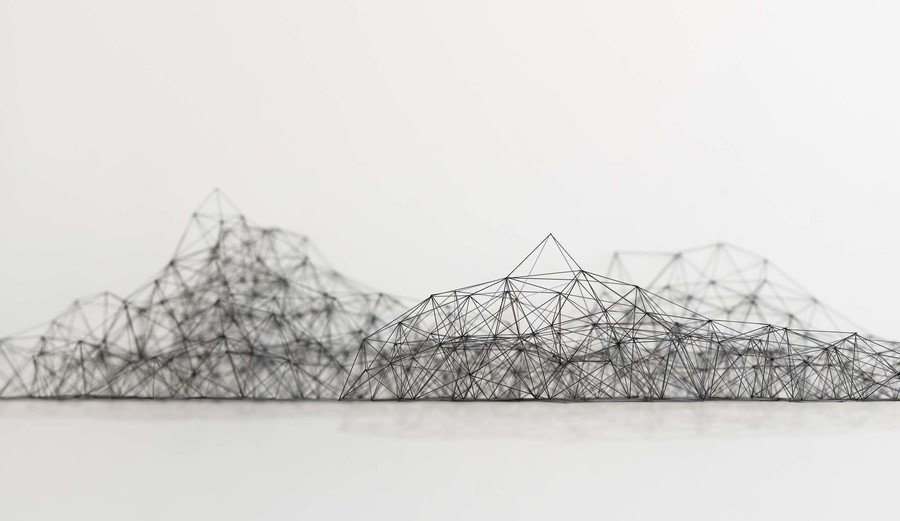

Peter Trevelyan survey #4 2013–14. 0.5 mm mechanical pencil leads. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū,

purchased 2014

I go into the Gallery. Haven’t been there in a while. Building closed. It was open to begin with. Civil Defence HQ in the weeks following the shock that laid the city low and who knew glass could be so strong, so resilient? Then the Gallery closed. It was cordoned off, behind wire netting. Something was going on in there. Someone said something had cracked in the basement. Someone said they needed to insert a layer of bouncy forgiving rubber beneath glass and concrete, ready for any future slapdown.

It feels good, going into the Gallery. Feels like civilisation when, outside, the swamp has bubbled back and the frail fabric has been torn away and we’re back to river bed. Feels like a layer of civilisation. Bouncy forgiving civilisation, our cushion against cyclical slapdown.

There’s an exhibition. Above Ground. About cities. Buildings.

Panoramic photographs of old Christchurch, people walking about or riding their bicycles between sturdy Edwardian masonry. How safe they seem, in their long skirts, in their lumpy jackets and cocky hats. Unaware of cracks, of faults. Alive and well in the Workers’ Paradise. All dead now. Rot. Bone. A thin layer of dust in France or the Dardanelles. Or over in the cemetery by Barbadoes Street. Eighteenth-century engravings of classical temples, classical façade, perfect rational geometry to be pasted over cities constructed on the proceeds of imperial rapine, invasion, genocide. A layer of ash.

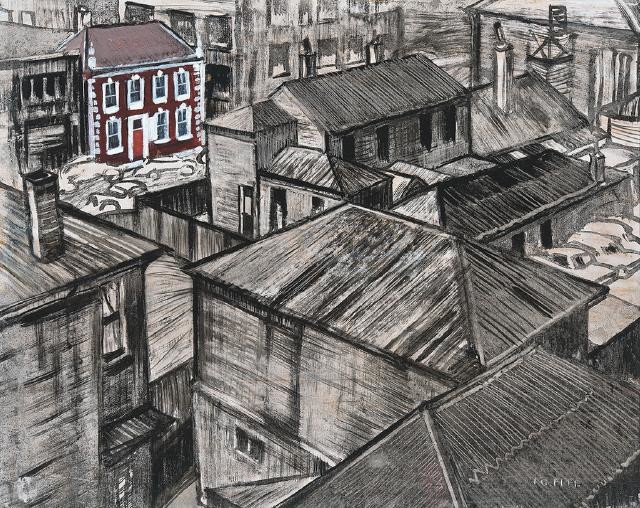

Paintings. So amazing, I always think, who cannot draw. How do artists do that? Suggest three dimensions on a flat plane? How do they see those colours, the hectic flush on a rumpty boarding house? How do they see the pallid cubes, the geometry of an industrial cityscape? How do they see the layers?

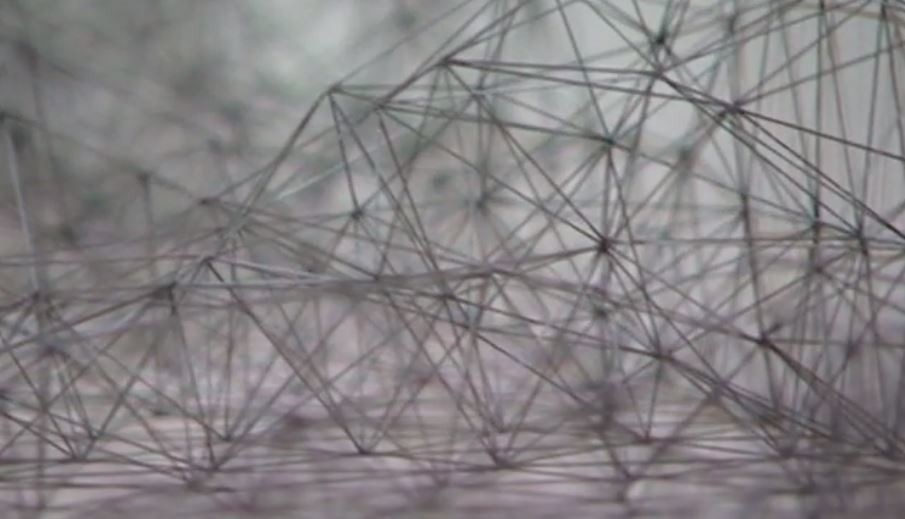

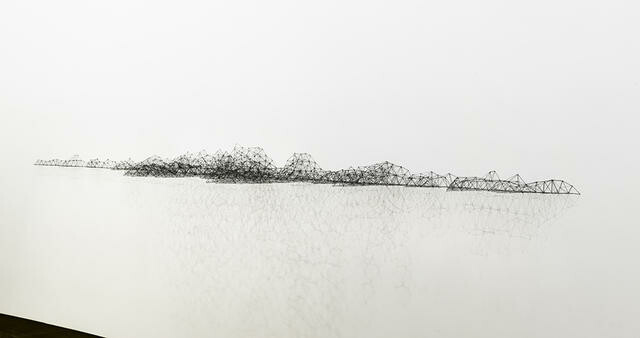

And on one wall, a web-like structure, several metres long. Low and horizontal, made up of interlocking triangles constructed from lead, the thin lead that’s found in a propelling pencil. Lead that snaps at the slightest pressure.

A little note attached. Peter Trevelyan. survey #4. Hung at eyelevel. Black and white, like those seventeenth-century engravings of Haarlem or London, where each building is individually identified, their steep gables and steeples making fretwork of the city skyline. Or closer to home, one of those trigonometrical maps of this country created from the deck of a bouncy sailing ship. The spine of mountains. Foothills. Coastal plains. Harbour inlets. River mouths. Swamps. Cliffs.

The preliminary survey. Preparation for what came after. Harbours measured in fathoms so ships might anchor. Load up with timber, gold, flax, coal. The country’s beauty as yet unsullied. In silhouette. In geometry.

And beneath the work, on the wall, is its shadow. Cast by the gallery lighting through the structure onto white plaster. Its pallid twin. The deeper layer. The subtext that lies, has always lain, beneath our feet. The web that can pull the whole geometry askew, snap all those frail interlocking shapes. Dust.

I walk out of the Gallery. The image is pinned to the memory. Not foremost. That layer is taken up with the drive home and should I pick up some avocados, another 500gm of coffee on the way, or will that mean I’ll be late, get caught up in the traffic down Lincoln Road?

But Trevelyan’s work is there nevertheless. Something to think about as I drive through the city and out along the straight darkening roads to the Peninsula.

Fiona Farrell has published novels, short fiction, poetry and non-fiction, and currently holds the Creative New Zealand Michael King Fellowship. She lives and works at Otanerito on Banks Peninsula.