Doctor Jazz Stomp and the Webb Lane Sound

Let Those Heavenly Drums Keep on Drumming

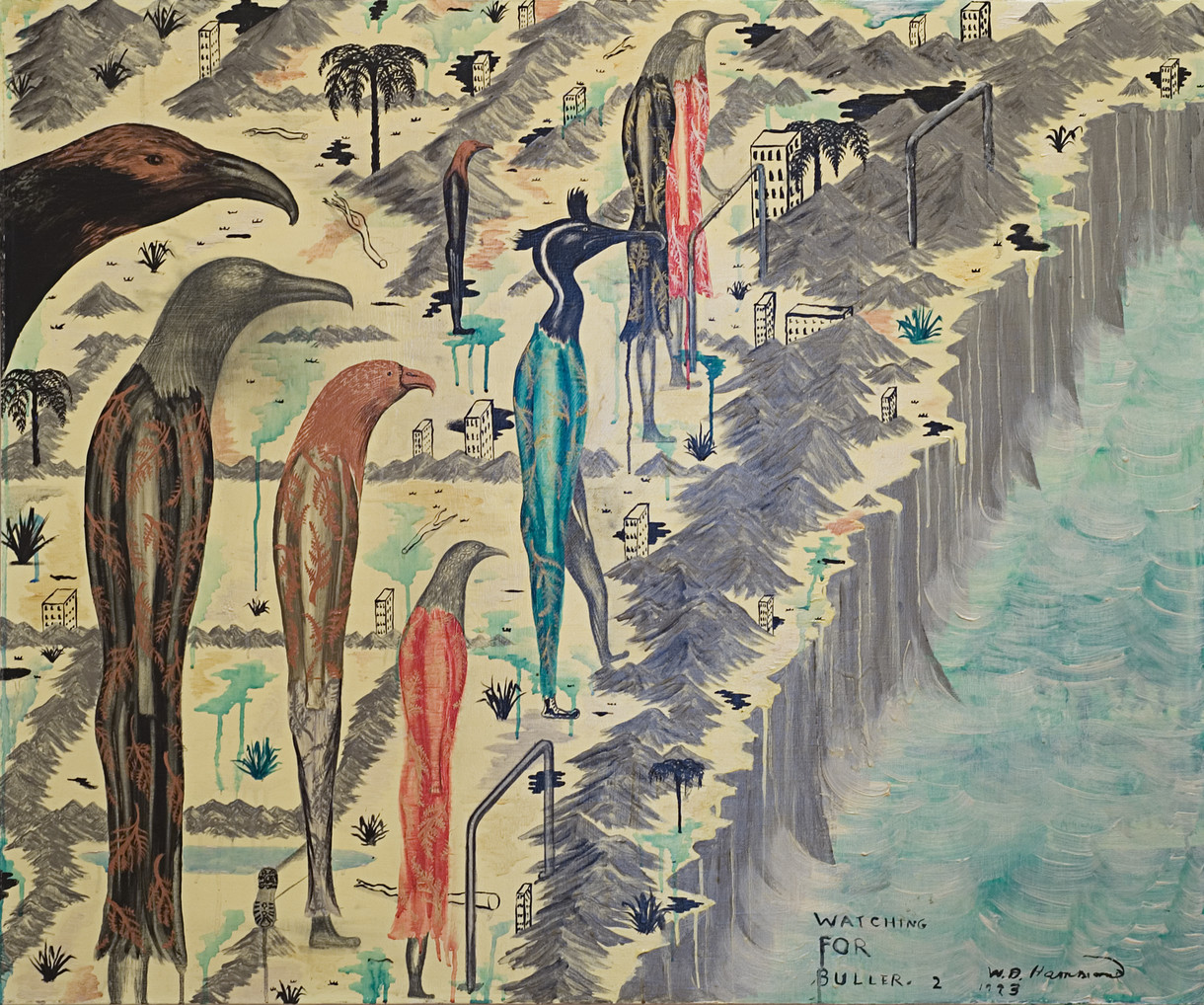

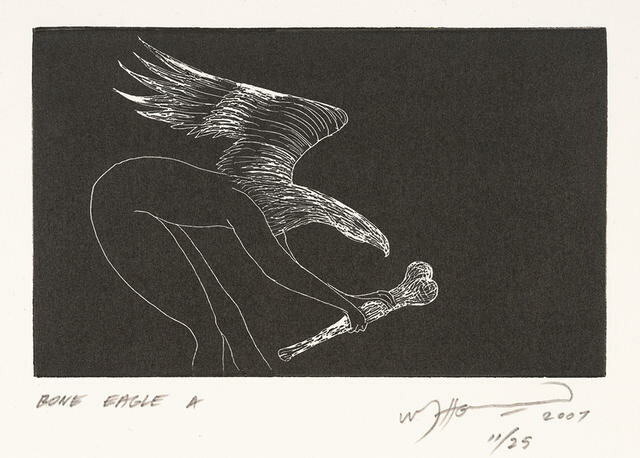

Bill Hammond Bone Yard Open Home, Cave Painting 4, Convocation of Eagles 2008. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and McLeavey Gallery

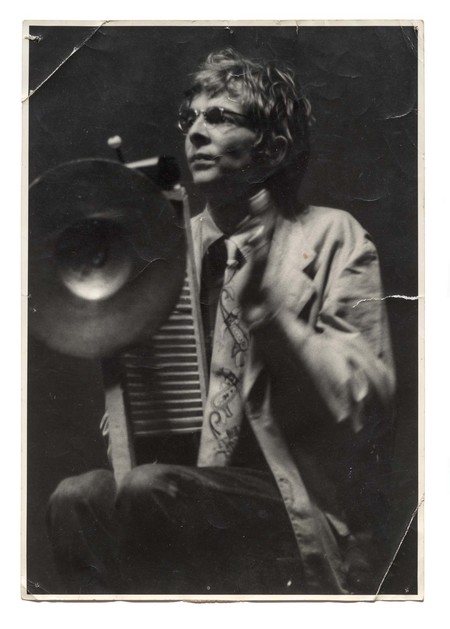

“Bill Hammond is long, lithe and tired, and was born several years ago. Is currently pursuing a Fine Arts course and trying hard to catch up. He is deeply interested in the aesthetic implications of sleep, sports the Rat-Chewed Look in coiffures for ’68, and dreams about blind mice in bikinis. He has never been known to sing outside the confines of his bedroom. Shows a marked but languid preference for the subtle textural nuances and dynamic shadings of washboard, cowbell, woodblocks, claves, cymbal, spoons, thimbles, tambourine, and the palms of the hands in percussive contact.” 1

Bill Hammond playing percussion with the Band of Hope Jug Band around 1967. Photo: Tony Ward

Drumming, percussion and an intense and wide-ranging interest in music have been constants in Bill Hammond’s life since he was a young boy out on the flatland suburbs of western Christchurch in the 1950s. Is it just me, or doesn’t every eleven-year old kid want to bang away on some drums? Drum up a storm in their neighbourhood and make their presence known sonically? Some of us had to improvise with kindling drumsticks, cardboard boxes and anything else with an inkling of percussive potential that may have been to hand. Bill was one of the lucky ones. His parents, Tom and Mavis, cashed in their son’s insurance policy to pay for his first drum kit when he was eleven – a brand new Beverley, the top of the line British drum at the time. Drums were to be a constant in Hammond’s life from this point.

Art was also there for Hammond from an early age as well. His father was supportive of his son’s interest and, a talented painter and decorator himself, taught him how to draw. There were nightly drawing lessons where the young Hammond was shown how to draw such things as a hoof, a hand, a horse or even his father’s Park Drive tobacco packet. 2 After attending Burnside High School during the early 1960s Hammond began studies at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts in 1966. His time at the art school coincided with a major folk music boom in Christchurch and the rise of New Zealand’s folk scene. And so, alongside his budding art career, Hammond’s interest in percussion saw him forming one of New Zealand’s most popular folk bands of the day, the Band of Hope Jug Band, in which he played a ‘trap set’ including tambourine, washboard, spoons and ‘percussive devices’.

The Canterbury University Folk Music Club was formed in 1964 and was soon filling the Repertory Theatre on Kilmore Street. Other central Christchurch venues included coffee bars and nightclubs such as El Segundo, King Bee, the Stage Door and the Plainsman Niteclub and were regularly packed out by folk bands. When the Folk Centre opened in October 1967, local and national folkies played with occasional internationals such as the Dubliners and members of Fairport Convention, who also sat in for some after-hours sessions at the Folk Club in Bedford Row. 3

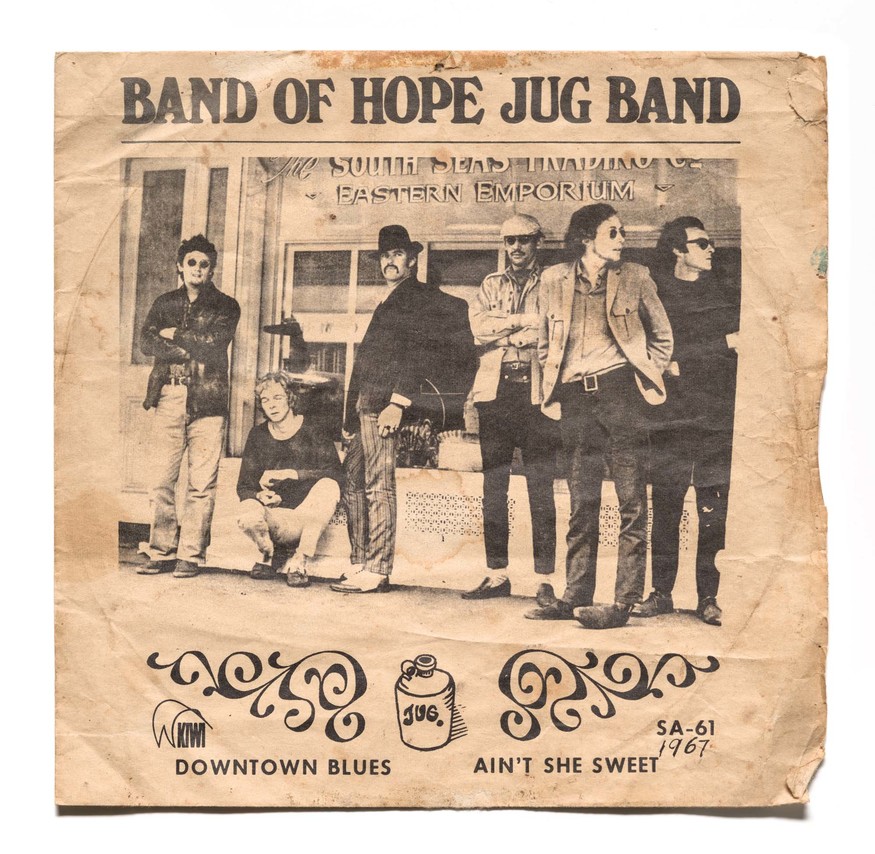

Cover of Band of Hope Jug Band’s ‘Downtown Blues’ 7 '' single, Kiwi Records, 1967

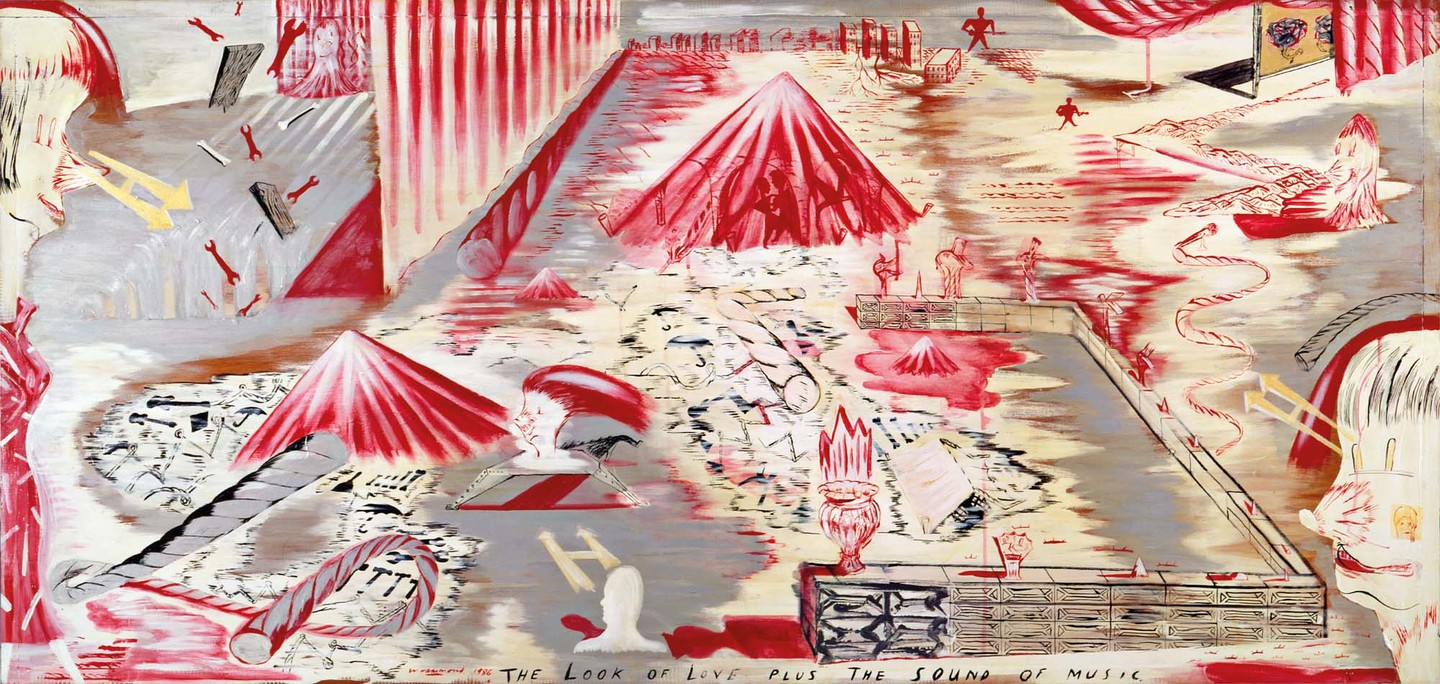

Photographer Mark Adams, who was a year behind Hammond at university, recalls seeing the Band of Hope Jug Band on numerous occasions and describes Bill’s washboard playing as legendary. (Mark went on to form his own jug band – the W.C. Fields Jubilee Memorial Junk Spasm Band – in which he played bass.) Certainly when listening to the extremely rare vinyl releases of the Band of Hope Jug Band (three 7” singles and an LP) Bill’s clickety-clackety-tap-tap-clackety-tap washboard adds an incredible sense of rhythm. The guy can hold down a beat, extend it and bend it over on itself. Hammond got the spotlight treatment with the release of the single ‘Coney Island Washboard’, in which he plays lead washboard. Intense, unrelenting, frenetic, fast and fun, the washboard rhythm conjures up similar feelings of intensity as I find when looking at some of Hammond’s earlier paintings like The Look of Love Plus the Sound of Music – a wonderful landscape painting brought inside and presented as if it’s a stage setting. Justin Paton has said of Hammond’s earlier paintings, “He does strange things with the acoustics of his rooms. The space will be weirdly funnelled or laid open or it will be concertinaed … Your eyes are being pulled around the space in a way that you are simply not used to. The effect of those paintings is this kind of incredible cacophony.” 4 There’s a fast-paced visual rhythm to many of his paintings from this period, and as Paton says often your eyes are dragged around the imagery at a frenetic pace, just like your ears are pulled this way and that when listening to that famous spontaneous be-bop drum off between Elvin Jones, Art Blakey and Sunny Murray in Copenhagen in 1968. 5

Bill Hammond The Look of Love Plus the Sound of Music 1986. Acrylic on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1986

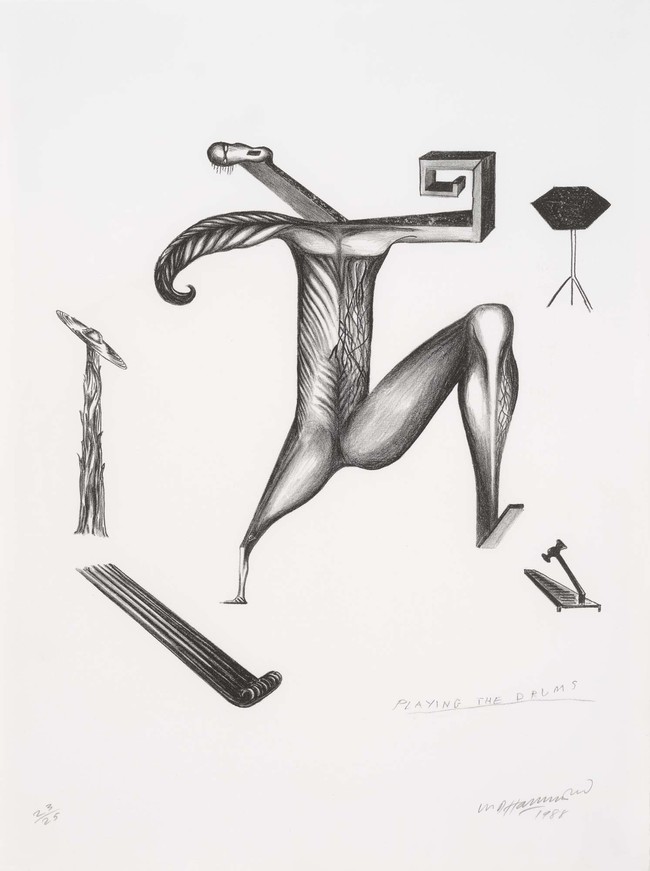

Rock drummers and guitarists, classical musicians, DJs and flamboyant singers all make appearances in Hammond’s work, often accompanying song titles or lyrics – The Tattooed Bride, The Look of Love, Love Will Tear Us Apart, Radio On, All Shook Up, Not Fade Away, Lose This Skin and You Make My Heart Sing. One of Hammond’s early exhibitions at the Brooke Gifford Gallery was titled Lines from Songs. My favourite is Playing the Drums, a lithograph based on a painting of the same title. Here, the drummer is possessed with those far-away eyes, listening rather than looking, gazing off into the void as he plants the beat down. Four on the floor – one foot pumping away on a hammer kick pedal, the other suspended above a long wave of shimmering ride cymbal, the feathery arm delicately tapping on a cymbal while the other arm folds out machine-like and thumping the electronic snare drum with robotic precision and timing.

By the early 1970s Hammond had left the flatlands of Christchurch and settled in Lyttelton where he has lived ever since. I was fortunate enough to visit his studio at the old Masonic Lodge on Canterbury Street, on a couple of occasions before it was damaged by the earthquakes. This building actually housed two studios. Up the stairs past an array of beautiful Jason Greig monoprints, then through the door and into the vast hall where some of his recent large eagle paintings were scattered, propped up on a raised stage that went round the edge of the room or pinned on the walls, while paintings in progress were sat on easels… The other studio, which immediately caught my attention, was across from the entrance downstairs; a drum kit sat pride of place in the middle of the room. Hammond had had special acoustic rubber flooring laid, which meant he could bang away on those drums anytime he liked without annoying the rest of the town.

Bill Hammond Playing the Drums 1988. Lithograph. Private collection

Hammond’s current Lyttelton studio overlooks the harbour and on my last visit loud music was blasting away as he worked. He’s a retired drummer now, having given his last drum kit to his grandson, but there in the corner of the studio sits a beautiful old Beverley floor tom, repurposed as a table for his paint tubes and brushes but never far away.

Bill Hammond: Playing the Drums brings together a wide selection of Hammond’s work, early and late, from some of his smallest works on paper to some of his largest paintings on canvas. One highlight will be the opportunity to see The Fall of Icarus, a Christchurch Art Gallery collection favourite, on the wall for the first time in over a decade. Another will undoubtedly be the inclusion of Bone Yard Open Home, Cave Painting 4, Convocation of Eagles. Painted in 2008, it is more than two metres tall and four metres long, with strong local connections that Peter McLeavey described as “the result of the artist’s perambulations around the hills of Lyttelton and Banks Peninsula and Redcliffs / Sumner.” 6 This will be the first time Bone Yard Open Home has been shown in Christchurch and only the third time it has been displayed publicly. Bill Hammond is one of Christchurch’s own; the exhibition is a great opportunity for locals to see some well-known works alongside rarely seen paintings and drawings from the artist’s own collection.