Good game, but is it art

Pippin Barr The Artist Is Present (still) 2011

Like any young medium, video games increasingly find themselves the subject of that age old question: is it art? Play itself has a strong presence in the artworld, from Yoko Ono's all-white chess set Play It By Trust to the amusing interactions possible with Franz West's Adaptives, but video games are often regarded with suspicion. Aren't they all just shooting and looting? And even if they're not, how can you tell if they're art?

To the extent that context is king – this artwork is in a museum, that artwork is stuck to the refrigerator door with a magnet – we have some validation. Recently, the Smithsonian in Washington DC opened the Art of Video Games exhibition and the Museum of Modern Art in New York held a game-oriented conference called Contemporary Art Forum: Critical Play. And in fact at Critical Play there was never a whisper that digital games simply might not be art at all. Instead it was generally agreed that digital games are a medium of expression, an artform capable of yielding everything from the lame to the sublime.

True story: I was invited to the Critical Play event as an artist because last year I made a game called The Artist Is Present in which you attend a digital version of a performance of the same name by Marina Abramović. In the game, you enter the Museum of Modern Art, buy a ticket, and then walk through a series of gallery spaces until you reach the back of a long queue. Then you wait, potentially all day, for the chance to sit in a chair and look into digital Marina Abramović's eyes. When the game is shown in European galleries the virtual museum is almost always closed because it operates on New York time. You can't get in, all you can do is stand outside the door and wonder what's going on in there.

When I thought up the game I chuckled to myself about the idea of a game in which you just stand around in a queue. But when I actually made and played the game it turned out to be more interesting than that. The act of waiting was surprisingly intense, and the correspondences between gallery rules and video game rules came to the forefront. 'Don't touch' becomes a literal inability to touch any of the art, symbolic tape indicators of a performance space become an uncrossable line, and celebrities cannot jump the queue. MoMA becomes a Platonic museum.

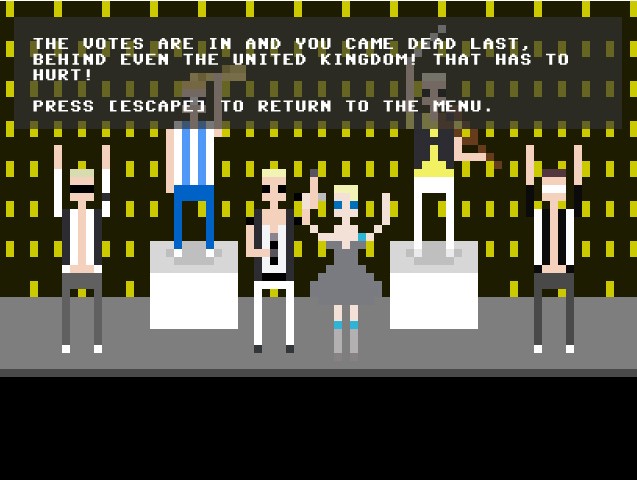

But although The Artist Is Present (the game) has been designated as art and is shown in galleries, most of my games haven't and aren't. For instance, I also made a game called Epic Sax Game in which you take on the role of a Moldovan saxophone player called Sergey Stepanov (known as Epic Sax Guy on YouTube), living the dream of getting to Eurovision. Trust me when I tell you that nobody called that one art, but a lot of people liked it anyway— even saxophonists.

When I made Epic Sax Game I wanted to allow people to have a small experience of musical performance. You can practice the little saxophone solo that the Epic Sax Guy played. Or you can ad lib and express yourself within the six notes available: A#, C#, D#, F, F#, G#. You can play most of the refrain from 'In The Hall of the Mountain King', for example. The virtual saxophone can even play chords.

For my money, it's that playfulness on the side of the player that's the most interesting and creative element of games. When we play games we're not always trying to score goals, shoot aliens, or fast-track our fictional careers. We don't always have to save the universe or rescue eggs from green pigs. We have other options. Sometimes we slip out of the mad rush to victory and find ourselves experimenting, playing, letting the universe go to hell while we dress up in a bright red space suit. These are things that aren't productive in any obvious way, but we want to do them anyway. They mean something to us.

We, the players, are making art in there. That's what should be art the heart of any 'games and art' debate.

Pippin Barr Epic Sax Game (still) 2011

In Skate 3 you're technically supposed to be skateboarding around a city performing tricks for photographers and participating in competitions for fame and glory. But step back only a small distance and you can start to appreciate each movement for itself. You launch yourself into the air, skateboard spinning on all its axes, and float framed against blue skies before landing and swooping off. As you get better at this, you're not so much skateboarding as dancing with a city.

In Red Dead Redemption you're a cowboy in a receding Wild West who kicks ass and takes names in an exceptionally bloody, almost genocidal, tale of revenge. But you're also living inside a surpassingly lovely series of landscape paintings created in a collaboration between your own choices and the game's world. Each town you set eyes on, each river you ford, each rocky vista you frame as you ride your trusty steed can form part of a self-curated exhibition.

In Minecraft you can veer away from the more obvious activities of sword fighting with zombies and building castles to take on more personal challenges. It's possible to replace a mountain with glass, for example, smelting sand into glass blocks and then painstakingly excavating the surface of the mountain and positioning the glass in its place. Then you can sit back and watch the sunset from inside your glass mountain while the zombies stumble and groan outside and know that it's a beautiful thing.

In many games we find ourselves dancing via the movement controls, stopping to stare at and frame the beautifully rendered world around us, or making our own sculptures with the materials available. In fact, this is one of the best and most foolishly kept secrets of video games. It's not so much that we should regard games themselves as stand-alone works of art to be placed in museums with game designers credited as artists, it's that we, as players, collaborate with games to make our own artistic experiences and expressions. That's what makes games special.

The art isn't just in the game, it's also, perhaps much more, in our play.

In Art Game, a game I haven't made yet, you create sculptures with Tetris blocks, make performance art as Mario, and paint paintings with Snake. After you've created a number of these artworks, you have a big show at a gallery. You go to the opening to look at the digital people looking at your work. They ask you questions. They ask, 'But is it art?' And you can reply however you like.

Pippin Barr

Pippin Barr is a digital game-maker, critic, and teacher currently working at the Center for Computer Games Research at the IT University of Copenhagen.

Rockstar Games Red Dead Redemption (still) 2010. Reproduced with permission