Unutai e! Unutai e!

Kāi Tahu and Anne Noble

Anne Noble Taranaki Stream, farm runoff (detail) 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Unutai e! Unutai e!

Ko te wai anake, te au e riporipo ana ki mea roto, ki mea awa, ki te nuku o te whenua?

Aue taukuri e!

Pupū ake a Muriwai Ōwhata i a roimata He manawa piako te Papa ā-Kura o Takaroa

Waimate haere ana te waiora Kai hea rā taku ika e?

Kai hea rā te oraka mō taku iwi e!

What has transpired?

Only the rippling waters of this lake and of that river can be heard flowing across the land

Muriwai Ōwhata is over-flowing with tears

The great hīnaki of Māui, Te Papa ā-Kura o Takaroa, is like a hollow and empty heart

The life-giving waters are turning brackish and undrinkable

Where have our fresh water fish species gone?

Where are our people able to thrive?

“Who are we when we can no longer feed our manuhiri with the kai for which we are renowned?”

Kia ora. We invite you to immerse yourself in our tribal story and reflect on this pivotal moment – one that calls us all to take action in protecting the world around us.

Unutai e! Unutai e! harnesses the power of contemporary art to shed light on an urgent environmental crisis: the deteriorating state of fresh water across Ngāi Tahu tribal lands. In 2020, Ngāi Tahu filed a statement of claim with the High Court in Ōtautahi Christchurch, seek-ing recognition of our rakatirataka over wai māori within our takiwā.

To support this claim, Te Kura Taka Pini, the division of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu responsible for the case, enlisted photographer Anne Noble to capture and document the crisis. Her role was to provide an impartial perspective – capturing our people in their chosen waterbodies while also revealing the widespread environmental degradation we witness daily across Te Waipounamu. What began as a photographic assignment evolved into an extensive visual archive, illustrating not only the devastation but also the resilience of whānau, hapū and iwi striving to restore wai māori, uphold rakatirataka, and protect mahika kai practices.

These practices are integral to Ngāi Tahu identity and survival. They compel us to ask the existential question: Who are we when we can no longer feed our manuhiri with the kai for which we are renowned?

The individuals in these photographs represent the many who have supported us over the past decade, and we are deeply grateful for their dedication, wisdom and commitment. The landscapes captured are just a glimpse of the hundreds of waterways that are taoka to Ngāi Tahu.

This exhibition begins at the pūtake mauka – our ancestral mountains, the source of fresh water. It then journeys through the polluted waterways before concluding with a vision of hope – projects dedicated to restoring balance and finding solutions.

But this is not just our story – it is a shared responsibility. The degradation of wai māori is not isolated to our takiwā; it is a crisis that affects us all. Water is the essence of life, binding us together across cultures and generations. The images you see are not just records of loss but calls to action. They remind us that with knowledge, persistence and collective effort, we have the power to heal our waters, restore our ecosystems, and honour the legacy of those who have come before us.

Without our collective efforts, the status quo remains. The future of our wai māori, our people and generations to come depends on what we do now.

“Ko wai kē mātau e kore e taea te whākai i ā mātau manuhiri ki te kai i rokonui ai mātau?”

Kia ora. Tomo mai koe, kia ruku mai ki te kōrero o tō mātau iwi, ā, ka āta whakaarohia tēnei wā whakahi-rahira – he mea e karaka mai nei, he mea e whakaaraara mai nei kia korowhiti atu mātau ki te kaupare i te ao e noho nei tātau.

Ka whakarērea e Unutai e! Unutai e! te whakaaweawe o te toi o nāianei kia whitikina ki tētahi āhuataka totoa, ki tētahi āhuataka mōrearea: ko te whakaparahako haere o te wai māori puta noa i kā whenua katoa o Ngāi Tahu. I te tau 2020, i te tāpaetia e Ngāi Tahu tētahi tauākī kokoraho ki te Kōti Matua ki Ōtautahi, ko tō mātau rakatirataka ki te wai māori ki roto i tō mātau takiwā te take.

Hai taunaki i te kokoraho nei, i taritaria e Te Kura Taka Pini, tētahi peka o Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu e kawea ana te mana o tēnei take, te kaiwhakaahua Anne Noble, kia whakaahuria, kia whakapūkete-hia tēnei tairaru pōautinitini. Ko tāhana, he whakarato i tētahi tirohaka matatika – Ka whakaahuria tō mātau iwi ki ō rātau ake wai, kai huraina ana te rakiwhāwhātaka o te tūkino ki te ao tūroa e kitea ana e mātau puta noa i Te Waipounamu rā atu, rā mai. I tīmata hai hinoka whakaahua, ā, i kukune ake ki tētahi pūraka wharaurarahi ā-kanohi, ehara i te mea e whakaaturia ana te whakamōtī anake, ekari he whakakiteka hoki o te kiri tuna o kā whānau, o kā hapū, o kā iwi e whakapau werawera ana ki te whakamāori anō i te wai māori, ki te tū rakatira anō kā rakatira, ā, ki te pupuri tou ki te mahika kai.

Ka noho ēnei mahi hai pūtake māria ki te tuakiri me te oraka toutaka o Ngāi Tahu. Ka ākina tātau te ui atu i te pātai tauoraka: Ko wai kē mātau e kore e taea te whākai i ā mātau manuhiri ki te kai i rokonui ai mātau?

Ko rātau kai ēnei whakaahua, ka noho hai kanohi o te tini mano i noho hai tuarā mō mātau i te kahuru tau ko hori, ā, e whakamānawanui ana mātau ki tā rātau ū titikaha, ki ō rātau kura, ā, ki tō rātau manawa tītī hoki. He karipihaka mata anake kā horanuku ko whakaahuaria o kā taoka arawai e hia rau nei o Ngāi Tahu.

Ka tīmata te whakaaturaka nei ki te pūtake mauka – ko ō mātau mauka tipua, te matatiki o te wai māori. Kātahi ka whāia ka ara ki kā arawai parakino i mua i ā rātau putaka atu ki te arokanui o tūmana-ko – ko kā hinoka e ū tou ana ki te whakatikatika, ki te whakataurite, ā, ki te whai rokoā anō hoki.

Ekari, ehara tēnei i tā mātau kōrero anake – he haepapa tahi tēnei o te katoa. Kāore te whakapar-ahako o te wai māori i tētahi pāka kino ki tō mātau takiwā anake; he parekura ka pā ki te katoa. Ko te wai te toto o te whenua, ko te whenua te toto o te takata e tuia nei tātau ki a tātau, puta noa ki ahurea kē, ki whakatipuraka kē. Ehara i te mea he mauhaka kōrero o kā mea ko karo, ekari ka karakahia nei mātau ki te poupourere. Kia maharatia mai, mā kā kura o nehe, mā te manawa tītī, mā te tū pakihiwitahi te oraka māria o ō tātau wai, te mana ki te whakarauora i te ao tūroa, ā, te whakarakatira i kā tukuka ihotaka o rātau mā.

Ki te kore tātau e tū pakihwitahi ana, ka mau tou ki taua āhua tou. Ko te anamata o tō tātau wai māori, o tō tātau iwi, o kā uri whakatipu ka whakawhirinaki atu ki ā tātau mahi o te nāia nei.

Gabrielle Huria (Ngai Tahu, Ngai Tuahuriri)

Chief executive Te Kura Taka Pini, Tumu Whakarae Te Kura Taka Pini.

Whakamāori: Tēnei te Ruru Ltd.

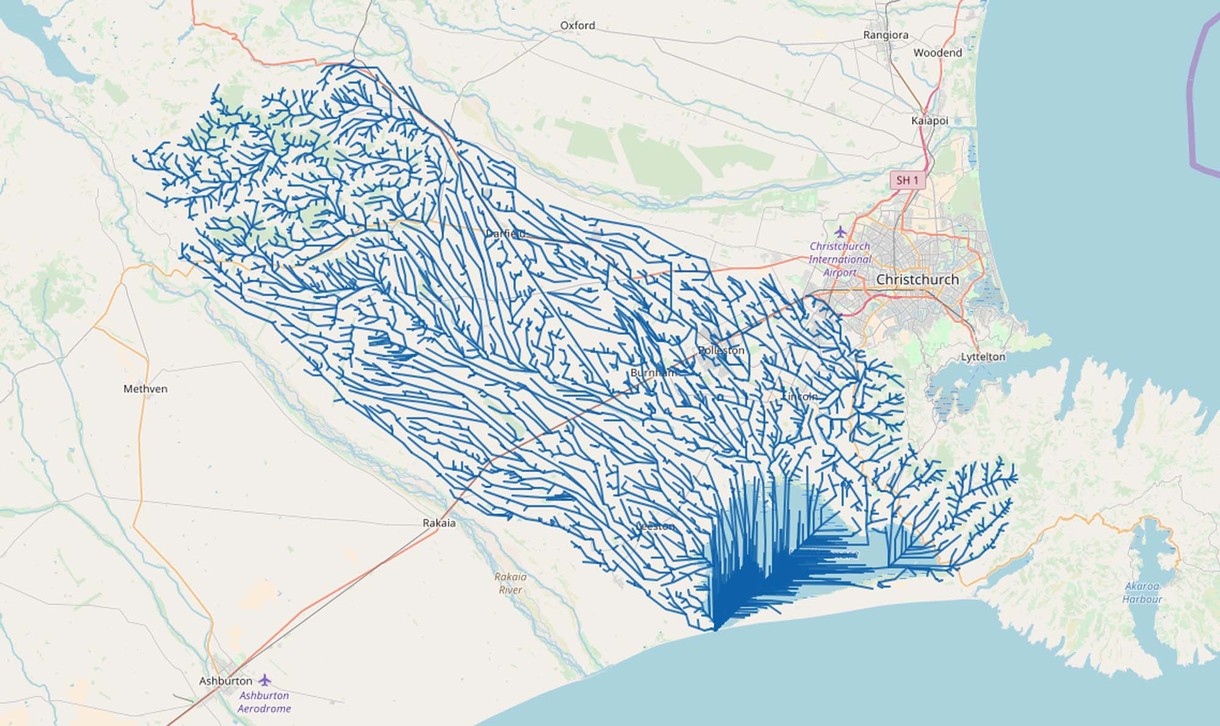

Rakahuri Ashley River

Te Maire Tau (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri)

Upoko o Ngāi Tūāhuriri, first plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae Tuatahi ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble Rakahuri Ashley River Estuary, toxic algal bloom in a now degraded and depleted mahinga kai site 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

What stands before me is a river that’s a shadow of its former self. People accept this as the Rakahuri today, but that’s not how it was. The name Rakahuri refers to the fact that the waters were strong enough to pull the trees out of the banks. Raka means to pull the stumps – to draw them out – and huri is to turn, so they’d be turned over and over by the time they got to the mouth. And that’s really a commentary on the power of the river, because it was a proper river with a strong flow.

One of the interesting things about the Rakahuri is that when we were young, our community would live on the river. We would camp there to get food, and we were permitted to live there through a Land Court Order that applied to our reserves on the river and some of the tributaries.

Tuahiwi families would relocate to these reserves in August, and they would camp there right through to November, getting whitebait. Every family had its hut and what you had was a thriving community living along the river. There might have been about twenty huts and houses with all the kids running around. They’d catch the school bus from there. They really did live off the river and it was all maintained and looked after.

Many New Zealanders wouldn’t know this, but in the 1980s we were forcibly relocated by the County Council. They removed our huts and prohibited any more camping on our river. This was despite a legal order from the courts that permitted us to do so. Our people were removed, and those camps no longer exist.

Now what we’ve got is the extinguishment of a river. The Rakahuri starts inland, it becomes a network of farm drains, water is taken out of the river for irrigation. Farm run-off is poisoning the waters of the tributaries and the lagoons with toxic silt and effluent, the fish life is under threat, the bird life is under threat – the environment is under threat.

The Rakahuri Ashley is an indicator of the slow destruction of all our riverways that is happening right now before our eyes. These are not the Canterbury Rivers that our ancestors knew and that the early settlers knew. What we are looking at is a wasteland. What should be sand and gravel is like a septic tank pit. There is faecal content in it. You feel ill eating the food from here.

We used to get watercress along the creeks and tributaries – but look at it. You wouldn’t get watercress out of this. I have, and it stinks. You can’t eat it and you certainly wouldn’t put it in a hāngi.

What’s happening here is that we are all bearing the cost of the environmental impacts of intensive dairy farming. We want to save these rivers – for the tribe, for Christchurch, for Canterbury and for the entire New Zealand public.

Anne Noble West Lees Valley looking towards the Puketeraki range, the source of the Rakahuri Ashley River 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Ko tēnei kai mua i ahau, ko tētahi awa, he tohihī noa tēnei o te awa tārere i rere i kā wā o mua. Whakaae ana a ētahi ko te Rakahuri i ēnei rā, ekari, ehara tērā tōhona āhua i mua. Hākai ana te ikoa, Rakahuri, ki te au kaha o te wai, e pērā ana te kaha i tōia kā rākau i te pārekareka. Ko te ‘raka’, ko te huhutitaka atu o kā kōtumu o te rākau, ā, ko te ‘huri’ ko te mahi a te awa, e takahurihuri ana i kā rākau tae noa atu ki te pūwaha o te awa. Kōia he takika kōrero mō te kaha rere o te wai o tēnei awa, i te mea he awa tūturu, he au kaha ōhona e rere ana.

Ko tētahi o kā āhuataka pārekareka mō te Rakahuri, nō mātau e taitamariki ana, e noho ana tō mātau hapori ki te awa. Ka noho puni mātau ki te mahi kai, ā, i whakaaetia tā mātau noho e tētahi Ture Kōti Whenua i tū ki ō mātou whenua rāhui ki te awa, ki ētahi hoki o ōhona kautawa.

Ka nuku atu kā whānau o Tuahiwi ki ēnei whenua rāhui i te Whā, ā, ka noho puni rātau tae noa ki te Whitu e hao īnaka ana. I ia whānau tō rātau ake wharau, ā, he hapori tōnui e noho ana ki te roaka o te awa. Kai te takiwā pea o te 20 wharau me kā whare, ā, e omaoma noa ana kā tamariki. Ka kakea te pahi kura i reira. Ko te awa te oraka tūturu o aua whānau, ā, i tiakina, i atawhaitia ngā mea katoa.

Ko te nuika pea o kā kiritaki o Aotearoa, kāore i te mōhio ki tēnei, ekari i te kahuru tau 1980, i kāhakina atu mātau ki wāhi kē e te Kaunihera. I turakina ō mātau wharau, ā, i rāhuitia te noho ā-puni ki tō mātau awa. I pēnei rātau, ahakoa he ture nō te kōti i whakaae ki tā mātau noho ki reira. I kawea atu mātau, ā, ko karo kē aua tōpuni i ēnei raki.

Ināianei, ko te mea ki mua i a mātau, ko te whakatīneitaka o tētahi awa. Kai tuawhenua te hikuwai o te Rakahuri, ā, ka huri hai whatuka waikeri ahuwhenua, ko tako te wai i te awa ki te hāwaiwai i kā ahuwhenua. Mā te wai tuhene nō kā pāmu kā kautawa me kā hōpua wai e paitini ai ki te parakiwai tāoke, ki te parapara tāoke, whakaraerae haere ana hoki kā ika me kā manu - ko te taiao tou e whakaraerae haere ana.

Ka noho mai ko te Rakahuri hai paetohu o te orotā ukauka o ō mātau arawai katoa kai mua tou i tō mātau aroaro. Ehara ēnei i kā awa o Kā Pākihi-whakatekateka-a-Waitaha i mōhiotia e ō mātau tīpuna, i mōhiotia rānei e te takata pora. Kai mua i a tātau he whenua tuakau. Te tikaka ia he onepū, he kirikiri, ekari he kura rua parakaingaki kē. He hamuti kē ki roto. Ka māuiui koe i te kai i ngā kai nō konei.

I mua rā, i kohia ā mātau wātakirihi i ngā awaawa, i nga kautawa – ekari, titiro. E kore rāia e kohi wātakirihi i konei. I pērā au, e, he hauka. E kore e taea te kai, e kore rāia e tukuna ki te umu.

Ko te mea e pahawa nei, mā mātau te utu o kā pāka kino ki te taiao o kā pāmu ahumīraka kakati e kawe. Kai te hiahia mātau ki te whakaora i ēnei awa, mō te iwi, mō Ōtautahi, mō Waitaha, ā, mō te marea katoa o Aotearoa.

Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere

Dr Elizabeth Brown (Kāi Tahu, Taumutu)

Chair, Te Taumutu Rūnanga / Toihau o te Rūnanga o Taumutu; executive director, Office of Treaty Partnership University of Canterbury / Kaihautū Matua, Te Tari Mana Tiriti, Whare Wānanga o Waitaha; plaintiff for the Ngāi Tahu Freshwater Statement of Claim / Kaiwhakapae ki te Tauākī Kokoraho Wai Māori o Ngāi Tahu.

Anne Noble Huritini Halswell River, entering Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere 2024. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

I remember my taua, Aunty Ake, talking about how the lake was clear enough that you could see the shingle on the bottom. When we were growing up it was never a consideration that you couldn’t just swim in the lake, or that you needed to think carefully about how healthy the fish were. Nowadays the number of times there are restrictions on accessing the water because of toxic algae increases every year, which means we can’t have total confidence that we can do our mahinga kai practices safely.

The biggest change in my lifetime is the quality of the water. Te Waihora has become the polluted repository at the end of all the rivers, tributaries and waterways that drain into it through the farmland around it.

Taking a ki uta ki tai approach, we can’t just think about Te Waihora, we must think about how all the rivers, tributaries and waterways feeding into Te Waihora impact upon water quality. While Ngāi Tahu had the lakebed returned as part of our treaty settlement, we got it back in a very degraded state. We have nitrates and phosphorus feeding into the lake, as well as the legacy of phosphorus and nitrogen sediment within the lakebed that will cost millions of dollars to remedy.

Eighty percent of the wetlands around Te Waihora have gone, and they were a key supporter of water quality and our mahinga kai practices. Originally the lake was four metres deep and when you drove through Lincoln, the waters of Te Waihora would have been lapping on the shores of the town. That tells you how much the lake has shrunk and the extent of wetland loss.

Currently, when the lake level rises to about 1.3 metres there is a risk of farmers’ land around the lake edge being inundated. This triggers a discussion about the opening of the lake, but we would prefer the lake is kept at around about 1.8 metres to improve the quality and quantity of the water and assist us to carry out our mahinga kai practices. We also need some wetland restoration to restore mahinga kai habitat and to address the turbidity of the water and the suspension of legacy nitrogen and phosphorus in the lake. So, there is a clash of cultures to negotiate. How do we reach a balance between our values and needs and the needs of the farming community when higher lake levels and wetland restoration projects impact on the economic viability of land at the perimeter of the lake?

Our vision for wetland restoration is to restore the mauri and the mana of Te Waihora. Te Waihora is our identity, it’s who we are. It is part of the life of Taumutu, and degradation of our lake reflects on us and affects our identity as Te Ruahikihiki. It is the environment that shapes our culture – not the other way around. Without the wetlands, we no longer have the access to our mahinga kai practices and that then changes us significantly as a people.

Anne Noble Waikirikiri Selwyn River, entering Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere 2024. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Mahara ana au i taku taua, Hākui Ake, e kōrero ana mō te mārama tou o te wai o te roto, i taea te kite i te kirikiri ki te takere. I a mātau e tipu ana, kāore i paku whakaaro mō te kaukau ki te roto, ki te oranga rānei o ngā ika. Engari anō ēnei rā, te hia nei ngā wā ka rāhuitia te toronga atu ki te wai i te mea ka piki tou te nui o te pūkohu paitini i ia tau, hai aha? E kore rāia e whakapono e taea ana e mātau te puta haumaru atu ki te mahinga kai.

Ko te panonihanga nui i te wā ki a au, ko te hekenga o te horomata pū o te wai. Ko huri Te Waihora hai purunga parakino kai te pūwaha o ngā awa, o ngā hikuawa, o ngā arawai e rere atu ana ki reira i ngā pāmu e karapotia nei te roto.

Kai tā mātau aronga ko ‘Uta ki Tai’, ehara i te mea ka whakaaro anake mō Te Waihora, engari me whakaaro hoki mō te rere iho o ngā awa, o ngā hikuwai, o ngā arawai katoa ki Te Waihora me te pānga o aua wai katoa ki te horomata o te wai i reira. Ahakoa i whakahokia te takere o te roto ki a Ngāi Tahu i te kerēme, i whakahoki parangetungetu mai. He pākawa ota, he pūtūtaewhetū e rere atu ana ki te roto, ā, kai te parakiwai ki te takere o te roto kē he pūtūtaewhetū, he pākawa ota nō ngā ngahuru tau i mua, e hia manomano tāra te utu ki te whakatika.

Waru ngahuru ōrau te nui o ngā repo o Te Waihora ko ngaro, ā, he mea whakaora wai matua, he wāhi mahinga kai anō hoki aua repo. I ngā rā o mua he whā mita te hōhonu o te roto, ā, ka hautū waka koe ki Lincoln, ko ngā wai o Te Waihora ko paki atu ki ngā tahataha o te tāone. Mā reira koe e mōhio mō te hekenga mārie o te wai, me te korahi o te whakatahenga o ngā repo.

I nāianei, ka piki ana te kārewa o te roto ki runga ake i te 1.3 mita, ka waipukehia te whenua o ngā kaipāmu kai ngā pārengarenga o te roto. Mā konei ka tīmata te kōrero mō te whakapuare i te roto, engari anō mātou, e pīrangi ana kia 1.8 mita kē te hōhonu o te wai, kia ora pai ai te wai, kia nui pai ai te wai, e taea ana e mātau a mātau mahinga kai te tutuki. Kai te hiahia hoki ki te whakarauora anō ngā repo, kia pai ai te mahinga kai, kia ora ai te whaitua, ā, kia kore nei e ehu tou ai te wai, kia māmā ake te kawe i te pākawa ota, i te pūtūtaewhetū i te mauroa ki te roto.

Heoi anō, he tukinga tikanga hai matapaki mā te Māori me te Pākehā. Ka pēhea e whakataurite ai ngā uara, ngā matea me ngā matea o te hapori ahuwhenua ina e pā kino atu ai te pikinga o te hōhonu o te roto me ngā hinonga whakaora repo ki te oranga toutanga o te ōhanga o te whenua kai te āwhiotanga o te roto?

Ko tō mātau arongapū ki te whakarauoratanga mai o ngā repo, ko te whakaora anō i te mauri me te mana o Te Waihora. Ko Te Waihora tō mātau tuakiri, ko mātau tou ko Te Waihora. Ko Te Waihora te oranga o Taumutu, ā, ko te āhua parangetungetu o te roto, he mea whakahuritao ki a mātau, ā, ka pātahi mai ki tō mātau tuakiri hai uri o Te Ruahikihiki. Ko te taiao kē te kaiwhao o tā mātau tikanga – ehara i te mea ko te tangata. Ki te kore he repo, kāore he mahinga kai, ki te kore he mahinga kai, ka tino rerekē rawa atu nei mātau hai tangata.

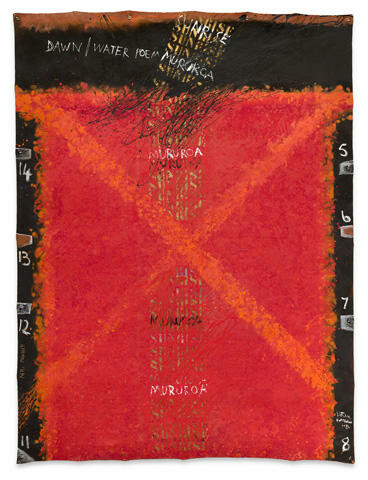

Taranaki Stream Te Awaawa o Taranaki

Gabrielle Huria (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri)

Chief executive Te Kura Taka Pini, Tumu Whakarae Te Kura Taka Pini.

Anne Noble Dominic Murphy, Taranaki Stream, Whanau inanga site 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

The Taranaki was always a very gentle place to whitebait. It’s good for the older people because they’re not having to battle the winds and the strong incoming tides like the younger men do out at the mouth of the Rakahuri.

Our family wakawaka is here on this part of the Taranaki. My grandfather and his brothers built one of the early floodgates and our whole family history is connected to the Taranaki and the Rakahuri. We are responsible for maintaining the wakawaka in the season. You look after it. You go down pre-season and make sure everything’s tidy, otherwise you lose your rights to be there. My cousin held the rights after his mother and grandfather died and when he recently had a stroke, my family have now taken over that responsibility.

The 2024 season was the first time in our whole family history that we couldn’t whitebait here. The water is foul. It is too dirty. Some brave relations still go there and whitebait, but I know too much about the science and what is in that water to risk it.

The hard thing for me personally is that every time we fish here, we know we are doing the same thing that our ancestors have done for generations. This is who we are. But if we can’t practice our mahinga kai, and if we can’t pass our traditions on to our kids because there’s nowhere to fish anymore, who are we? And I don’t want to be part of a generation that saw the destruction of our culture and our values. We are facing an existential crisis, and the reason we are taking a claim to the High Court is to fight for all we are losing – not only for us. Our fight is for everyone.

Consecutive governments have failed all the people of the South Island. Whereas fifteen years ago our rivers were clean, from the eastern seaboard to Otago and Southland, they’re genuinely filthy, overallocated for irrigation and unswimmable, and it’s getting worse every year.

Who said this is acceptable? It’s not acceptable to us. Pollution and environmental destruction are happening fast. The decline in the quality of our waterways has crept up on us since agriculture was enabled to transfer to intensive dairying on a huge scale. No one is holding those responsible for the resulting environmental degradation to account.

For the last fifteen years we’ve been putting our efforts as a tribe into researching how these catchments work. We marry our collective traditional knowledge with the science. We are thinking carefully and know that things must change to ensure future generations can benefit in the way we have. The reason this work is so important to us as a tribe is so we can be the conscience that holds the government to account. The Taranaki was once a beautiful little river. When I can smell a clean river, I know where I am, but this river smells sick and sad. If our Taranaki had feelings – and I think it does – I wonder what it might be telling us?

Anne Noble Taranaki Stream, farm runoff 2023. Digital print, pigment on paper. Collection of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

He wāhi māmā te Taranaki hai wahi hao īnanga. He pai ki ngā taua me kā poua i te mea kāore he hau e pūawhe kino ai rātau, ā, kāore he tai pari e whakararu ana i te tangata pēnei i ngā taitamatāne kai te waha o te Rakahuri.

Kai konei, kai tēnei wāhi, te wakawaka o tō mātau whānau. Nā taku poua rātau ko ōhona tuakana-taina tētahi o ngā ahuriri tuatahi i hanga, ā, ko te kōrero tuku iho o tōhoku whānau katoa ko herea ki te Taranaki, ā, ki te Rakahuri anō hoki. Nō mātau te haepapa whakapaipai i te wakawaka i roto i te tau. Ka tiakina. Ka haere atu i mua i te tīmatanga o te tau kia mōhio ai koe, he pai rānei, he tika rānei, ki te kore, ka ahimātao tō ahi. Nō taku karangatahi te mana i te matenga o tōhona hākui, o tō mātau poua hoki, engari inatata nei pāngia ia e te ikura roro, nā reira, nō tōhoku whānau ināianei taua haepapa nui.

Ko te tau 2024 te tau tuatahi i te kōrero tāhuhu o tōku whānau kīhai i taea te hao īnanga ki konei. I te pīrau te wai. He paru rāia. Ka haere tou ētahi whanaunga mātātoa ōhoku ki te hao, engari nā taku mōhio ki te pūtaiao, ki ngā mea kino kai te wai, kāore au i te hiahia tūpono atu ai ki taua kino.

Ko te mea uaua ki a au ake, ia wā ka puta ki te hī, ki te hao rānei, kai te tino mōhio mātau e mahia ana e mātau te mahi tou a ō mātau tīpuna nō ngā reanga e hia kē nei ki mua. Ko mātau tēnei. Engari ki te kore e taea te mahinga kai te mahi, ā, ki te kore e taea te tuku iho i ā mātau tikanga ki ā mātau tamariki i te mea kāore he wāhi e pai tou ana ki te mahi ika, ko wai hoki ia mātau? Kāore au i te pīrangi, ki tōhoku reanga tou, te kite atu i te orotā o ā mātau tikanga, o ō mātau uara. He tairaru tauoranga kai te aroaro, ā, ko te take e kawea atu ana e mātau tā mātau kaupapa ki te Kōti Matua, ko te whawhai ki te pupuri ki aua mea e ngaro haere ana – ehara i te mea mō mātau anake. Mō te katoa tēnei whawhai.

Kāwana atu, kāwana mai ko mūhore tā rātau tiaki i ngā tāngata o Te Waipounamu. Ngahuru mā rima tau ki mua, he mā ngā awa katoa, ināianei, mai i te ākau rāwhiti, tae noa ki Ōtākou, ki Murihiku, he paru tūturu, he nui rāia te whakaratonga hāwai, e kore e taea te kauhoe, hai ia tau e piki ake ana te kino.

Nā wai ia nei tēnei āhua i whakaae? Ehara nā mātau. He tino wawe te parahanga, me te orotānga o te taiao. Hūrokuroku ana te paru haere o te horomata o ngā arawai, ko paru ake nei, ko paru ake nei i te whakaaetanga o te mahi ahuwhenua ki te whakawhiti atu hai pāmu ahumīraka kakati, hai pāmu kau korahi. Kāore tētahi i te whakawhiu i te hunga nā rātau te taiao i parangetungetu.

Nō ngā tau ngahuru mā rima, i te āta whai, i te ngana, hai iwi, ki te rangahau i te rerenga o ēnei riu hikuwai. Kai te āta whakaaro, kai te mōhio hoki mātau, me panoni ā tātau mahi kia whai hua ai ngā uri whakaheke pēnei i a mātau. Ko te take he whakahirahira rāia te mahi nei ki a mātau kia taea ai e mātau te tū hai ngākau whakawā e whakatikaina ai te kāwana.

Ko te Taranaki i mua, he awa ātaahua. Ka rongo ana au i te kakara o te awa mā, kai te mōhio au kai hea au, engari ko tēnei awa nei, he haunga kē, he māuiui. Ina he whatumanawa tō te awa nei – ko tāku e whakapae nei, āe he whatumanawa tōhona – he aha kē pea āhana kōrero mai ki a mātau?