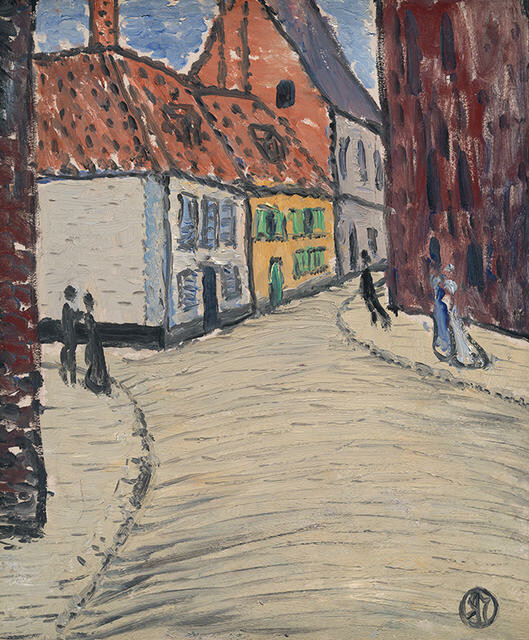

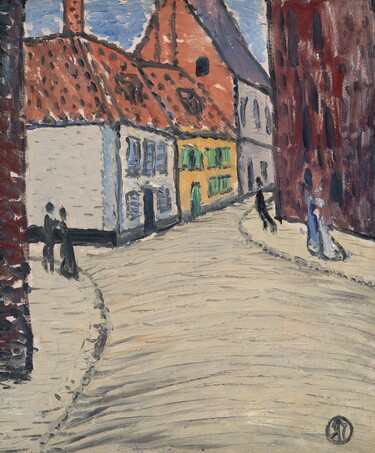

Raymond McIntyre Street in Saint-Valery-sur-Somme c. 1913. Oil on panel. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased with assistance from the Barbara Anne Ford bequest, 2025

Raymond McIntyre

Heave a brick at the clock, smash the ornaments, boil the piano

It’s been too long a time between exhibitions for expatriate Waitaha Canterbury artist Raymond McIntyre (1879–1933) here at the Gallery. Although his work is regularly included in group exhibitions, the last focused survey was forty years ago when Raymond McIntyre toured to the Robert McDougall Art Gallery. Maybe a few of our readers remember this exhibition, but it feels like time he was introduced to a new audience.

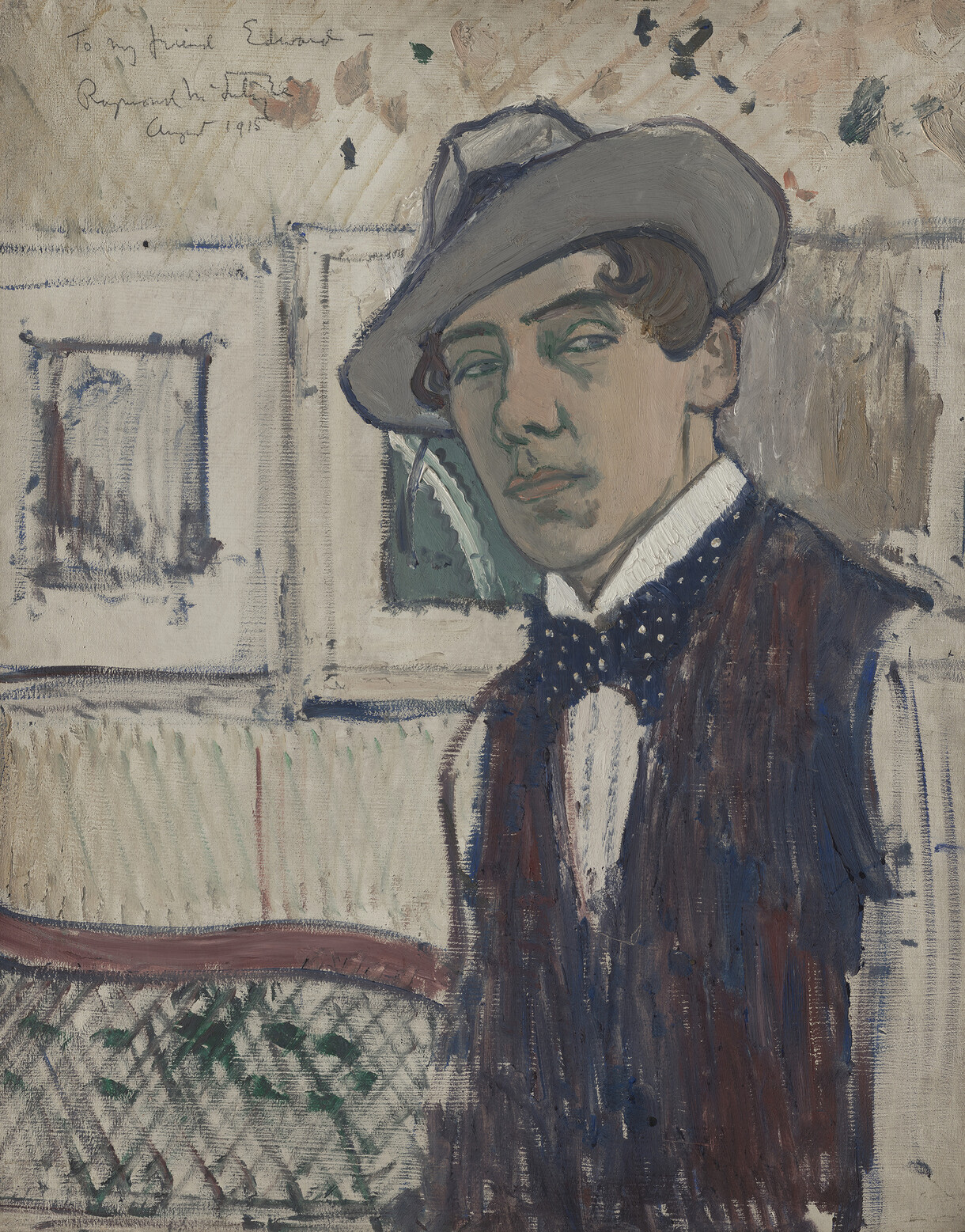

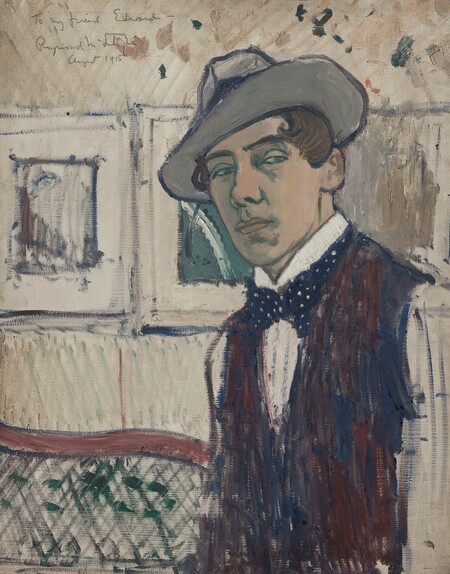

Raymond McIntyre Self Portrait 1915. Oil on wood panel. Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, gift of the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts, 1941

McIntyre was born in Ōtautahi Christchurch in 1879 to an upper middle-class family – his father was a successful businessman and mayor of New Brighton. It was a comfortable upbringing and the family lived in Wainoni. During the early 1900s when McIntyre was developing as a painter it was still an area of wide open sand dunes and tussock country. Favouring the twilight hours of the setting sun, he relished painting this gentle landscape rather than the rugged mountains of Otira Gorge or the Southern Lakes that attracted so many of his contemporaries.

In 2023 the Gallery acquired a vibrant landscape painting, Three Trees, Sandilands, New Brighton, which had belonged to Evelyn and Frederick Page. Like the majority of McIntyre’s works, it is a very small oil painting on panel, but it carries an energised vision of the Wainoni landscape that belies its size. It’s a striking painting, and the artist used a palette knife extensively to lay the paint down in a very expressive manner. Progressive and loose in style, it was very unusual for a work produced in Christchurch in 1908. It is the sort of painting that McIntyre’s local reviewers decried as an “abomination”. One described feeling unable to “… praise a picture that is so unlike anything in nature we have ever seen.”1 With works such as this McIntyre certainly raised his head above the parapet and the conservative art establishment and reviewers of the time obligingly took aim.

By 1908, he had had enough. Faced with a lack of recognition and the outright ridicule of local reviewers, it was time for McIntyre to leave Aotearoa New Zealand and experience the contemporary developments in Western art in more progressive international centres. In January 1909, aged 30, he set sail for England and never returned to his home country.

In London, McIntyre found himself right in the centre of a key moment in the development of British art as it under-went a remarkable transformation. A few months after his arrival he noted in a letter to his father that, “In London one can see every conceivable style of work.”2 One crucial event was Roger Fry’s exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists, which opened in December 1910. Included were artworks by Manet, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse and Picasso that inspired a new and modern approach in British art. Although when McIntyre visited the exhibition he was not immediately won over by the works, the exhibition, and particularly the paintings of Matisse, eventually came to have an effect on his work. This exhibition is widely viewed as a critical moment in British art and culture, and it signalled a shift in attitudes away from conservative Victorian ideals towards a more contemporary approach to art. Virginia Woolf famously described Fry’s efforts in championing modern art in Britain at the time as an “Art-Quake on British art”.

At the time this exhibition was on, December 1910, McIntyre’s disruptive side is humorously summed up in a letter home to his father where he describes the numbing dullness of visiting his London relations, and what he wants to do to liven things up:

… saw the legs of the dining-room table nearly through – when it is heavily laden – and give it a “shove” when the family are assembled for food taking, and see if they would be astonished. Or say something frightfully shocking or dis-gusting. Heave a brick at the clock. Smash the ornaments. Boil the piano. This would probably do it good. Pull the heads off dogs and throw them in the fire. Slay the monkey. If they had one. Tear up the turtles. They haven’t any. Throw a bomb under the feet of the “heavies”. Calmly – when they are not looking – calmly I say, lift the roof off the house. I think even Mrs Campbell would glance up at the ceiling, with curiosity aroused as to what had happened.”3

For all this, the Campbells were to become important supporters of McIntyre during his later years.

Raymond McIntyre The Pavement, London c. 1913. Oil on panel. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by Mrs M. Good, London, 1975

By 1912 he had completed his studies under William Nicholson and Walter Sickert and given up on trying to get his work accepted for the Royal Academy, which was at the forefront of the conservative art establishment and some-thing aspired to by many young expatriate artists. McIntyre’s Self Portrait of 1915 highlights his growing confidence and reputation as an artist.

…with me it is an unfoldment, and when I do the work I want to do, there will be a place for it… As for the idea of going and studying under some well known man, my opinion regard-ing that also has decidedly changed since I left N.Z. One’s only chance is to be oneself.4

He wrote again to his father:

There is no doubt that o1cial (or Royal!!) recognition of Art has a very deadening effect. The R.A. [Royal Academy] is not in touch with the really significant things that are happening in the world of Art. The old order must pass, though. Well bother the R.A. anyway – away! – begone!5

McIntyre instead gravitated to the more contemporary New English Art Club and the London Group, which were spearheading modern developments in British art at the time. Throughout the 1910s he exhibited in numerous group shows alongside leading contemporary artists including Christopher Nevinson, Jacob Epstein and Paul Nash.

Another measure of McIntyre’s success during the 1910s was his work being reproduced in prestigious art magazines The Studio in 1914 and Colour between 1915 and 1918. For many in Aotearoa New Zealand The Studio was the main means of keeping up to date with international contemporary art. So it must have been a surprise for his detractors back in Christchurch when they opened that issue of the magazine to find McIntyre’s Phyllis reproduced with such prominence.

McIntyre supported his meagre earnings by taking students at his studio flat on Cheyne Walk opposite the Chelsea Embankment and overlooking the River Thames. This is the neighbourhood in which his favourite painter James McNeill Whistler had lived, and can be seen in McIntyre’s painting The Pavement, London. Among his neighbours were the feminist Sylvia Pankhurst and the Australian printmaker John Hall Thorpe, who shared McIntyre’s Christian Science beliefs and attended the same church meetings. In those early years in London, McIntyre is known to have caught up with fellow expatriate New Zealand artists Owen Merton, William Menzies Gibb and Grace Joel but surprisingly there is no record of him having met Frances Hodgkins, although the two would surely have been aware of each other’s presence and progress.

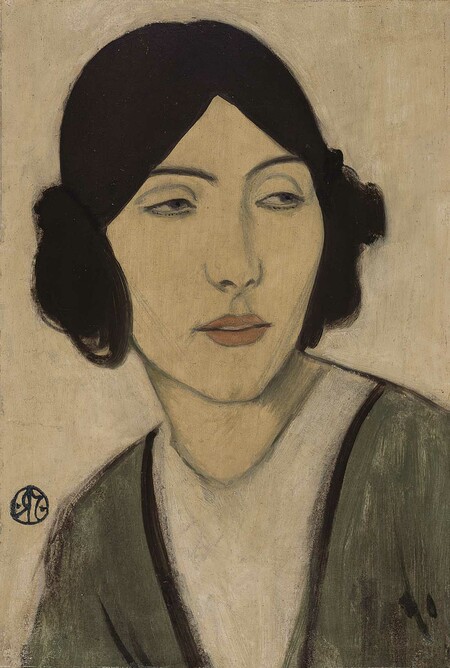

Raymond McIntyre Ruth c. 1913. Oil on wood panel Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the McIntyre Family through Miss F. M. McIntyre, 1938

While many of McIntyre’s contemporaries such as Sydney Lough Thompson, Hodgkins and Merton enjoyed travelling, living and working on the European continent, McIntyre himself seems to have been content to live and work in London. He is known to have made two trips to France, visiting Saint-Malo in Britanny and St-Valery-sur-Somme to the north in 1912 and Paris in 1920. These brief excursions appear to be the extent of his travels on the continent. In London he immersed himself in the culture on offer, enjoying the close proximity to all the art galleries, theatres and music venues the city offered.

McIntyre is best known today for a series of portraits of young modern women that he began in 1912. Small in scale and focusing on the head and shoulders, the subjects of these paintings are invented personas and represent an idealised beauty. McIntyre was candid in describing his approach to composing these portraits when he wrote to his father:

…I have invented her type. Though all the things I do are like her – yet it is the particular points about her which interest me and which I accentuate – and bring out – and I leave the parts that do not help. One [visitor] said what lovely hair she had. Now in this particular picture the hair was pitch black – and she hasn’t black hair at all. Whatever the scheme is, I vary the hair to suit it.6

His repeated depictions of hair coiled into buns over the ears was influenced by the customary hairstyle worn by women in Britanny that he had seen on his visit to Saint-Malo.

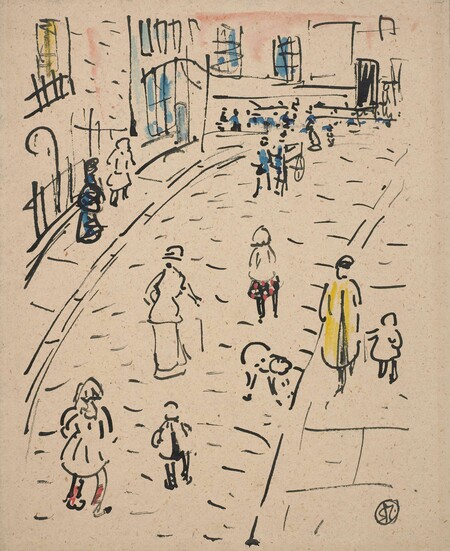

By late 1917 McIntyre had moved into a studio flat on Redcliffe Road, a short distance from Cheyne Walk. His flat overlooked the street and from this viewpoint he began producing a remarkable series of ink drawings of pedestrians coming and going or chatting together below. The use of ink provided McIntyre the opportunity to draw quickly and spontaneously, reducing his subjects “to a sort of shorthand in which nothing is lost of character and movement.”7 He would then add touches of watercolour to enhance the drawings.

Raymond McIntyre Street Scene with Figures c. 1917. Ink and watercolour on paper. Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, gift of the estate of C. Millan Thompson to mark the occasion of the retirement of the director, S. B. Maclennan, 1968.

In 1918 McIntyre held a major exhibition of forty-nine paintings and drawings at the Eldar Gallery in London. It was his only major solo exhibition during his lifetime. From this point on his profile as a painter begins to decline – although he continued to paint until his death aged 54 in 1933, he exhibited less frequently and his last public showing was in London’s Goupil Gallery Salon exhibition in 1926. The reason for this is unclear. He may have simply had enough of eking out a living on the limited income he received from his art. Although he was a full-time artist he never made a lot of money and relied heavily on regular financial assistance from his family in the form of the pound notes they enclosed with their correspondence. From 1923 he established himself as a noted art reviewer for the Architectural Review, which supplied a welcome regular income at this stage of his life.

In curating this exhibition, I was truly struck by how generous McIntyre’s family, friends and collectors had been throughout the twentieth century in ensuring his work entered New Zealand’s public collections. His work was rarely acquired by New Zealand galleries during his lifetime. The National Art Gallery, now Te Papa, received the extraordinary gift of McIntyre’s sketches, prints and paintings from the estate of C. Millan Thompson in 1968. McIntyre’s sister, Nina Slater, donated several excellent Christchurch period landscape paintings to the Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena in 1973. Here at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, McIntyre’s Christchurch family presented three key examples from his London period through his sister Hilda, and Mary Good, a close friend of McIntyre’s in London, gifted two key paintings in 1975. The remark-able painting Street in Saint-Valery-sur-Somme, recently discovered and repatriated from England, was acquired by the Gallery through the generosity of the Barbara Anne Ford bequest.

I missed McIntyre’s survey exhibition in 1985, so it has been an absolute treat to spend time looking at and learning about this remarkable painter’s life and art. Raymond McIntyre: A Modern View is an opportunity to celebrate the achievements of one of Waitaha Canterbury’s most successful expatriate artists, and one that I’m sure our audiences will enjoy.