Ko Te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa

An interview with Shona Rapira Davies

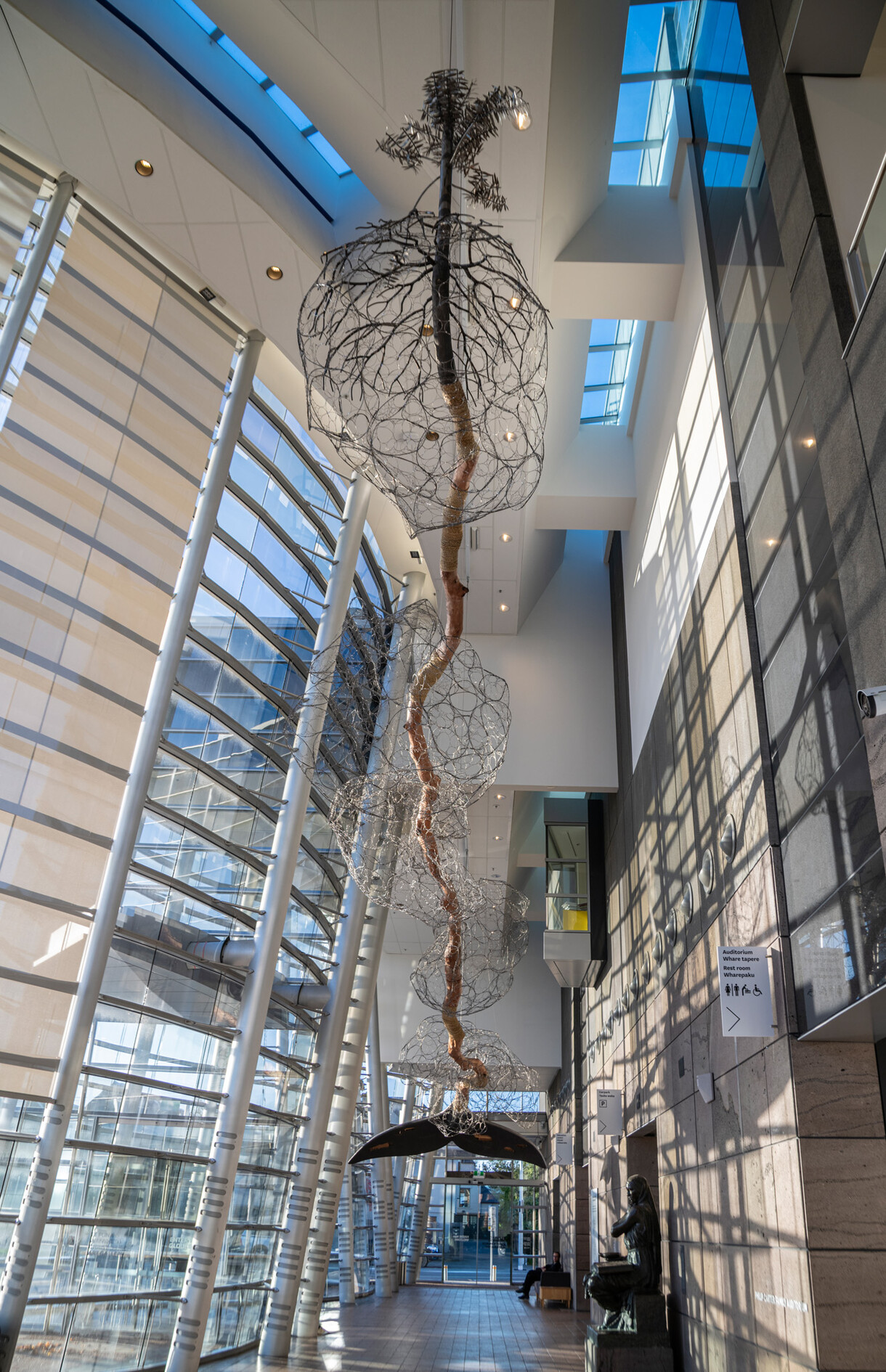

Shona Rapira Davies Ko te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa 2022. Pōhutukawa, steel wire, stainless steel bolts, plywood, graphite, harakeke. Courtesy of the artist

Chloe Cull: Tēnā koe Whāea, thank you for making time when I know how busy you are. We’re here to talk about your work – Ko te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa – currently installed in our foyer at Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery. Ko te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa has come here to Ōtautahi from Ngāmotu New Plymouth in Taranaki, where it was first commissioned by the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. It also brings with it kōrero from Aotea Great Barrier Island, where you’re from. Let’s start with Taranaki – can you talk about the specific history from there that this work responds to?

Shona Rapira Davies Ko te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa 2022. Pōhutukawa, steel wire, stainless steel bolts, plywood, graphite, harakeke. Courtesy of the artist

Shona Rapira Davies: The specific history is, of course, the attack and the violation of Parihaka and the killing of children. It happens in every single war to do with land anywhere – you kill the children because they’re the inheritors. You wipe out the old people because they carry the history. You rape the women to make them unimportant, and you take all the men because you need them to make the roads and stuff. That’s what the Taranaki men did: they built the roads from Wellington all the way down south to Dunedin. They were considered convicts. And they sent some of them across to be imprisoned on other islands.

There are two thing that shaped my understanding of this. One was the writings of Niccolò Machiavelli, who wrote a whole series on what you need to do in war, and how you go about that. You still see it playing out in Ukraine and many other places. How does [Putin] do stuff? He just wipes out the people. Gets hold of the men, puts them in prison. It’s the same as it was centuries ago. When I was young I was interested in what would bring a huge number of people to this place, thousands of miles from where they came from, to do such a heinous thing. Why did they think they had the right, and why would they do that? And then, how would they do that?

Well, they followed Machiavelli’s principles to the letter, didn’t they? And that happened not just in Waitara, it happened all over the country. When you take land, there is only one way to take it from the people who have it. It’s that simple. If it wasn’t by the point of a gun, it was by starving them as they walked away, it was by harassing them as they went down the road, it was by pushing them through enemy territory so they got wiped out.

So this work came from that context, and then things happened around the world that amplified that for me. One was Myanmar and the displacement and killing of the Indigenous Muslims there. They just got rid of them, killed them, destroyed burial sites.

I thought, “What can I do about these pēpis, these babies, that are affected by war?” We’ve got monuments all over the country for all these different wars. Well, there’s not one single monument for the children. I heard stories about the sound of children in the early spring in Waitara being like cicadas, like kihikihi, and that really resonated with me. That’s where the title comes from.

CC: Can you talk about the form of the sculpture – you have a tohorā or whale tale at one end, and a kauri sapling at the other. Where does that come from?

SRD: We have a story up north about how Kauri and his brother Tohorā heard their father Tangaroa calling from the ocean, saying “come to me, come to me”. Tohorā said, “I’m going to see my dad”, so he buggered off down the hill into the water. Kauri stayed with his mother on the land. And then one day Tohorā was swimming by and he heard his brother Kauri crying for help because the iwi wanted to chop him down. So in an act of truly laying down his life, Tohorā threw off his shield, his cloak, his skin, and he beached – he died to give the people there his body to use instead.

This is the essence of that work. It’s about giving up one’s life for one’s family, one’s whānau, as a child. I’m not talking about older people, I’m talking about the kihikihi, the tamariki in spring.

Shona Rapira Davies Ko te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa (detail) 2022. Pōhutukawa, steel wire, stainless steel bolts, plywood, graphite, harakeke. Courtesy of the artist

CC: While this work responds to the history of Taranaki particularly, there is a relationship to Ōtautahi too. In 1880, 160 men from Parihaka were brought to Ōtautahi and held captive on Rīpapa Island in Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour. Some of the men died in captivity and were buried on Ōtamahua Quail Island. The hapū at Rāpaki reinterred their bodies in their urupā at Rāpaki, and at the urupā there is a memorial to the mothers of those men. There’s something beautiful about there being a memorial at Rāpaki to the wāhine, and this memorial here to the tamariki, who are often the people forgotten in wartime.

SRD: That’s right. And that kind of resilience is so important, marking our presence through our history and our continued remembrance of that, rather than us slowly forgetting. It’s actually quite hard because I remember crying through most of the making of this work.

CC: You made the work as part of a team that included your whānau, is that right?

SRD: I did, yes. Members of my whānau, my install team of Chris Streeter and Martin Kelly, as well as a team of Taranaki whānau who helped on the install at the Govett-Brewster. Taniora Tamati-Rakete, who is Te Ātiawa, was a very important member of that team. My moko Rehutai was invaluable to the install in Taranaki and Ōtautahi. He knows how to weave, he just does.

He went up to spend time with Diane Prince to gain a bit more of an understanding and knowledge of harakeke. He was up there for a couple of days, and she sent him back and then I gave him the right to choose who could be in his team making the work. But he didn’t choose me!

As leader of a project like this, I don’t see myself as being a manager, my job is to make sure everybody is safe and supported by the kaupapa, and I produce all the food and the coffee, and say, “It’s okay”. At that end we can step back and say it’s a joint thing, and that’s the way it grows. Especially for young men – if young men said something I would really listen, because they have ears and eyes that are free of a whole lot of built-up processes that we might not be able to see through.

CC: The tail of the tohorā and the kauri sapling at the other end speak to that pūrākau of the brothers, but in what other ways have you brought your Ngātiwai whakapapa with you in the making and presentation of this work?

SRD: So my whenua at home... we’ve got very large, very ancient pōhutukawa trees. We’re talking two or three thousand years old. Tainui waka tied up to one of them, that’s how we know they’re old. I’m very proud of that. Pōhutukawa were also used as the waka tūpāpaku for our dead. Their long roots go all the way into the sea, and ours are so old they have these huge tentacle-like root systems. We used them over the centuries to make staircases back home too. Each one of those is like our tuākana. My aunties were talking all the time about them being sacred, and I remember when I was young, one of the boys was chasing a rabbit and it ended up going down a pōhutukawa hole. So then he lit a fire in the bottom to smoke it out but the tree caught fire inside and that fire became like a huge volcanic thing. I came around the corner hearing my nanny doing karakia and tangi, and it was hair-raising. It was awful, it was just – we were standing there while this old lady was calling and crying to this sacred tree who was her tuakana. It was the first time in my life I had ever witnessed that. And I realised for the first time what that meant. Because when we were little, you know, if you found a little bit of bone or something, you’d just push it under the tree, but it didn’t really connect on that sort of level, until that moment.

My sister remembers when she was swimming and she found a bone in the water and showed it to nanny, and she said, “Well, just push it under the tree”, because the tree had its root systems right into the seabed. That’s what it was about – we tied those that passed in the tree until all of their bones were released and then we had another ceremony and buried them in the many caves. The whenua up there is volcanic so little bubbles of lava have made caves so we also put them in there. Our trees are all like that, they’re our tuākana and I’ve never forgotten that.

The pōhutukawa that we used for this work wasn’t from home – it belonged to my dealer at the time. I couldn’t go home because of COVID so I had to hunt around for a tree. My dealer Penny had one in front of her house, and she said, “You can have my tree”. I said I had to go and talk to it, I have to make sure I’m okay with that because I don’t want anybody dying or hurting themselves. I went out, I have a chat with the tree and I sat there and just waited. Some tūīs came in and I thought, “Okay, this is the tree but we have to do it properly and say karakia and everything.” I’ve got pictures of them cutting it down and I was standing there and saying, “It’s okay”. It was sixty to eighty years old.

Every tree is important for me, especially pohutukawa, and that offering was gratefully accepted. We spent about eight months working on it, and I didn’t waste anything. I even boiled up the bark to make a black ink.

We were never, ever wasteful with our materials. I tried to follow my aunties’ example, those kind of processes. If I cut down a tree then there are things I have to do to ensure that everything is right, is tika. So that’s what the pōhutukawa was for. I couldn’t use anything else. I mean, I could have made one up, fabricated it, but I didn’t do that because I’m not talking about things European, I’m talking about things Māori, and that pōhutukawa signifies both life and death. There’s also the whole understanding of Te Kore and Te Pō inside of that, which is why I have mōteatea over the top.

"This is the essence of that work. It’s about giving up one’s life for one’s family, one’s whānau, as a child."

CC: As you say, the kaupapa of the work is heavy and tragic, but it’s on display in a very public, multi-use space. For example we have tamariki in the classroom next door coming through for their lessons, and events in the foyer. Can you talk about the role of that recorded oriori or mōteatea in terms of keeping everybody safe?

SRD: That mōteatea was given to me by Taipari Munro through Ngātiwai. I had to go to Ngātiwai first of all to be able to do this work because I’m taking one of our special stories and using that as a bridge between us and Taranaki. I took a little bit of time and effort from them too, for me to request – and I had to have all the drawings and everything sorted, and then just lay it down and say, “This is what I want to do”. And they were... when they saw the work in the end there was astonishment, but it took a wee while because this is in the modern format. Like, I have wire that is supposed to talk to the volcanic nature of Taranaki and Aotea. And I’ve got this big, long pōhutukawa tree, and I had to clarify, “Well, no, no, it’s not one of those, you know, tuakana trees from home.” And they accepted all that, because I had followed all the protocols for it. And then I asked for a mōteatea for it and they sent me Taipari’s one, and although it talks to flying over different areas of the Barrier, what it also does is fly over that work in the space to keep people safe, and at the end it talks about the crying child. It says “E Tama, tangi kino e!”

CC: I think it’s something that also helps people stop and spend some time with the work when they hear it. It invites pause and a sense of reverence around the work as well.

SRD: I suppose it has to do that because it’s in a multidisciplinary space that sometimes has food within it – that was my one thing, you cannot put this near food! And that’s why I used the mōteatea – to cover it and the space so that there was no chaos or anger as the result of it being in your place. It’s such a beautiful mōteatea. It’s one that Ngātiwai uses at every kaupapa.

CC: It’s lovely. Ko te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa has really transformed the foyer space – it’s an extraordinarily big work, isn’t it? But so are many of your well-known works, such as Nga Morehu. Do you conceptualise a work in advance at that scale?

SRD: I love three-dimensional space! When Megan [Tamati-Quennell] invited me to make something for the Govett-Brewster there was this wonderful space that went up like a cathedral, up the ramp to the Len Lye gallery. I said, “I want that one, and I also want that one down there”, which is the big wall space towards the toilets. I did Ko Te Kihikihi along the side there, which is a companion piece to Ko te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa. It talks to the actual wars.

So, I’m not scared of space. I really do try to do smaller work though, because then I wouldn’t be so bloody poor. Doing huge work also involves convincing people – I’ve got to get them really enthusiastic because it’s going to cost a wee bit. Funnily enough, if there’s mauri, if the work has mauri, people arrive to help!

There’s reasoning behind that, all the things that I do there’s always tohu or things happening that I allow to happen because they’re supposed to. Sometimes you don’t have all the skills that you need and I couldn’t make the works without those amazing people getting involved. You know how it needs to work, but you don’t have the skills to... like, I’m not going up fifteen metres to tie stuff to the ceiling…

CC: No, you need somebody else to do that.

SRD: I need somebody who loves getting one of those things that you have there, those lifts, you know. It’s serendipitous on one level but for me it’s also a tohu that I’m supposed to be doing something, and I was supposed to be doing this work. That’s how I’ve always worked. But I’m afraid the work is bloody big and I’m still poor and I look at those other artists and I really wish I was one of them because they can make a simple living.

CC: But you get the sense that it couldn’t be any smaller.

SRD: No. I can’t imagine Nga Morehu with only one figure, for example, or a little version. I can’t imagine Ko te Kihikihi Taku Ingoa any smaller – it had to go upwards to get that whole idea of space and elevation. I remember seeing that happening in real time: Hori Parata is a tohunga of tohorā, and when a whale died on the Barrier he came over, did karakia, and then he sliced some of the flesh from the tohorā and got his runner to run all the way up to the top where he could no longer hear the karakia, and then he buried it in the ground right at the top. And I needed to express that in the length.

CC: It’s a stunning work and we absolutely love having it in our whare, and so thank you, Whāea, for entrusting us with its care. We’re very grateful. Is there anything else you wanted to mention or talk about in relation to the work that you think is particularly important for people to understand?

SRD: I just think that you taking on board this big work was a real challenge and also an amazing effort on the part of Christchurch Art Gallery.

CC: Kia ora.

Chloe Cull spoke to Shona Rapira Davies (Ngātiwai ki Aotea) in October 2025.