Daisy Lavea Timo in promotional image for Brave—A Daisy Poetry Promenade

A Perspective on Pacific Art in Christchurch

Pacific art is one of the more internationally successful and innovative sectors of New Zealand’s art industry, but Pacific artists in Ōtautahi have struggled to be a visible part of the city’s cultural landscape. Due to our small population and distance from the Pacific art capital that is Auckland, our artists have often developed in relative isolation, relying on our Pasifika arts community to maintain a sense of cultural vitality, belonging and place within the city.

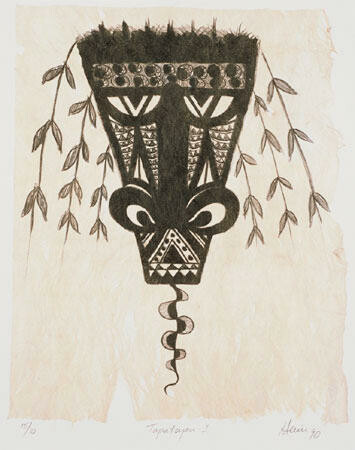

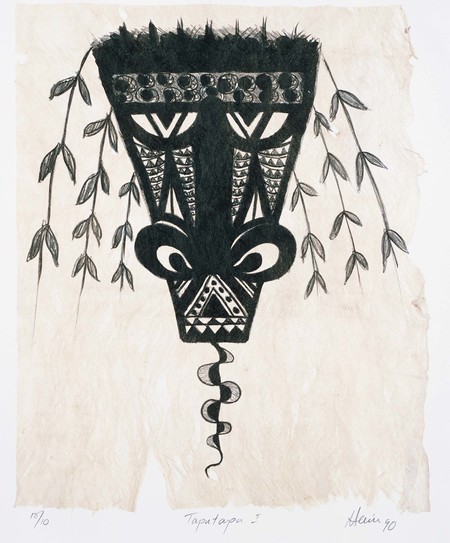

Fatu Feu’u Taputapu 1 1990. Lithograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1991

Intimately tied to identity and place, Pacific art flexes in and out of everyday life. For some artists, the notion of being categorised as Pacific still carries the stigma of difference and limiting expectations around what that implies. For others, it’s a difference that is integral to their experience and is deeply encoded in everything they do. All Pacific artists seek meaningful context and engagement with their work, but they often look for validation in the context of cultural institutions that predominantly serve the mainstream.

In Canterbury, this context was determined by the existence of our Pacific Arts Festival, the University of Canterbury’s Macmillan Brown Pacific Artist in Residence programme, tertiary courses on Pacific art, events like the Pacific Arts Association’s International Symposium (held in Christchurch in 2003), and exhibitions by Pacific curators. It was encouraged by galleries like the Salamander, which focused on developing a market for Pacific artwork, and by supporting galleries CoCA, Our City Ōtautahi, the Physics Room, Jonathan Smart Gallery and PaperGraphica and represented in collections at the University of Canterbury, the Canterbury Museum and Christchurch Art Gallery. These things all contributed to the visibility of Pacific art in Ōtautahi. But it is the people that activate these spaces and events who determine their success.

As the earthquakes shattered our buildings and performance venues, they also shook the foundations of our small arts community.

Lonnie Hutchinson Sista7 2003. Black building paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2003

A Pacific story

As the earthquakes shattered our buildings and performance venues, they also shook the foundations of our small arts community. One loss felt keenly has been Pacific Underground, which began as a creative vehicle for the likes of Oscar Kightley, Anton Carter, Dave Fane, Malo Luafutu (Scribe), Pos Mavaega, Dallas Tamaira, Joy Vaele and Shimpal Lelisi. As an independent theatre and music production company, Pacific Underground’s role extended to events management. Managers Tanya Muagututi’a and Pos Mavaega ran a central city office in the Christchurch Arts Centre and established the city’s annual Pacific Arts Festival. Forging strong relationships throughout the performing arts sector and within the Christchurch City Council, Pacific Underground became something of an institution, as did the festival. Providing a platform to develop and showcase local talent alongside more established artists, the festival’s focus was on Pacific entertainment. What began as a family day with a market, local cultural groups, dance crews, singers and musicians, grew to encompass an extended program of contemporary and heritage arts, workshops, exhibitions and evening performances.

Hosted in the Arts Centre, the festival delivered inspired collaborations and magical performances. It turned Christchurch into a tour destination for Pacific musicians and became a televised feature on Tagata Pasifika. Facilitating an inter-island flow of creativity, the festival encouraged the innovative spirit and professionalism of our arts community, but more importantly provided a relevant context in which to see ourselves as part of a colourful cultural landscape.

Eventually, managing the festival impacted on Pacific Underground’s other commitments and the festival celebrated its tenth and final year in February 2010. After 2011, the breakdown of the city’s infrastructure, especially in the east, forced Pacific Underground to move to Auckland. In their absence, the voice of Ōtautahi’s Pacific arts community was lost amidst the clamour to salvage what was left of the city’s creative industry. Not long after, the University of Canterbury decided to restructure the Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies and the Pacific Artist in Residence programme was discontinued.

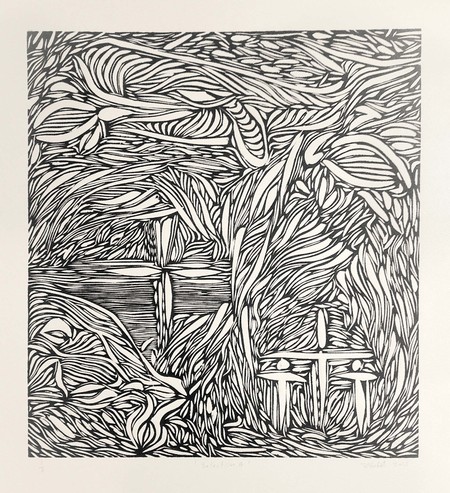

Josh Bashford Selection 3 2015. Woodcut on paper. Reproduced with permission, image courtesy of the artist

Home grown

The often conservative nature of Ōtautahi’s cultural and institutional landscape easily undermines the talent and cultural contribution of the Pasifika artists who regard Christchurch as home. Most reluctantly move north, but some flourish regardless. More than a decade ago Christchurch rapper Scribe’s musical debut, The Crusader, hailed his regional pride across the nation’s airwaves and we all learned to chant ‘not many, if any’. Similarly, for many years poet Tusiata Avia actively maintained her profile on the international poetry circuit from the eastside depths of Aranui.

Recently, the play Black Faggot, written by award-winning Christchurch-born Samoan playwright Victor Rodger, was performed in his home town, A multi-faceted coming out story, Black Faggot makes no concessions for polite society but was proudly presented as part of the 2015 Christchurch Arts Festival. While Rodger’s work plays to mainstream audiences in Auckland, Melbourne, Hawaii and Edinburgh, this was the first time in twenty years it had been commissioned in Christchurch.

Another South Pacific highlight in the 2015 Christchurch arts festival 2015 was the premier of The White Guitar. Produced and directed by Nina Nawalowalo and Jim Moriarty, The White Guitar was a family biography written by Malo Luafutu, his brother Matthias and father Fa’amoana, who performed on stage as themselves. As theatre born from the Christchurch earthquakes The White Guitar unveils the darker side of the Luafutus’ lives, the pains of migration, the effects of family violence and the unbounded legacy and redemptive power of creative expression.

The White Guitar was not just a story but an emotional homecoming for both the performers and those who lived alongside the Luafutu clan. Within Pacific circles, the musical prowess of Fa’amoana (John) Luafutu and the artistic talent of the Luafutu family is legendary. Malo Luafutu, Caroline Tamati (Ladi6), Mahalia Simpson (Australian X Factor), Matthias Luafutu (actor), Tyra Hammond (Opensouls) and artist Lonnie Hutchinson are all cousins. The White Guitar is a Christchurch story, a Pacific story revealing the strength of family and connections which underpin the collective nature of our individual expression.

Writing has been one of the more popular creative vehicles for the Pacific community. First Draft Ōtautahi Pacific Writers group was established in 2007. A year later they published their first illustrated anthology, Fika, and went into intermittent hibernation until 2011 when they regrouped as Fika Writers. Providing a forum for all genres of writing, from performance poetry to blogging, Fika have become the unofficial face of Pacific writing in Canterbury. The group facilitates support for younger writers and development through workshops with established writers, such as David Fane, Albert Wendt and Tusiata Avia.

Fika’s Danielle O’Halloran and poet Alice Andersen mentor a regional workshop series for Rising Voices, an Auckland-based youth poetry movement and national slam competition, inspired by poets Grace Taylor and Jai MacDonald. A global phenomenon, slam poetry has a strong youth following, and has become a powerful medium for the voice of Pacific youth. Last year, for the first time, a Christchurch poet, Sophie Rea, won the Rising Voices Grand Slam, and young Rising Voices Moana Thompson and Damien Taylor took the top two places in the Christchurch qualifier for the NZ Poetry Slam, going on to form the Faultline Poetry Collective with Sophie Rea and Courtney Petelo-Luamanuvae.

Two young Samoan producers are making their presence felt: Sela Faletolu of No Limits Theatre, supported by her partner, Silivelio Fasi, and Daisy Lavea- Timo, of Judah Arts Productions. Both women are leading the creative management of young performers in their school and church communities. Motivated by the need she saw for young people to have a voice and creative outlet following the earthquakes, Sela created No Limits. Speak Your Truth premiered at the Court Theatre in 2013, the first of many productions highlighting Pasifika youth issues. Collaborating with The National Academy of Singing and Dramatic Art, the majority of No Limits actors, singers and dancers are untrained but they perform sell out shows and evoke strong emotional responses from the audience. In contrast, Judah Arts Productions are a collective of experienced artists and musicians, who also work with youth. A recent performance was Brave—A Daisy Poetry Promenade at Aranui High School, a collaborative showcase of photography, music, spoken word and performance, woven into an experience of ceremonial Samoan art forms, including gift exchange and tattoo.

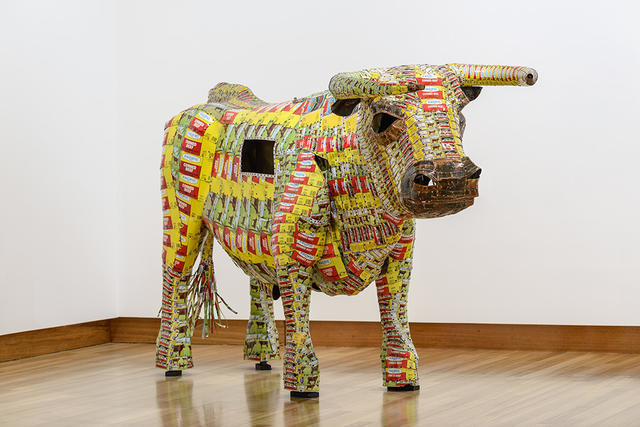

Historically Christchurch galleries have been graced with work by some of the best Pacific artists the country has to offer. Audiences have long been wowed by the likes of Lonnie Hutchinson, Michel and Sheyne Tuffery, Fatu Feu’u and Andy Leleisi’uao, but currently only a handful of Pacific artists actually live and practice here and most work or exhibit in relative isolation.

Residing in Aranui, Samoan carver Raphael Stowers’s tall pou carving Unification commands the entrance to Wainoni Park. Aside from his studio practice, he is also a carving tutor at Crossroads Trust. Working on the periphery of the art establishment, Raphael’s creations are stylistically eclectic. Inspired by a number of different carving traditions, his works bear a life and personality of their own.

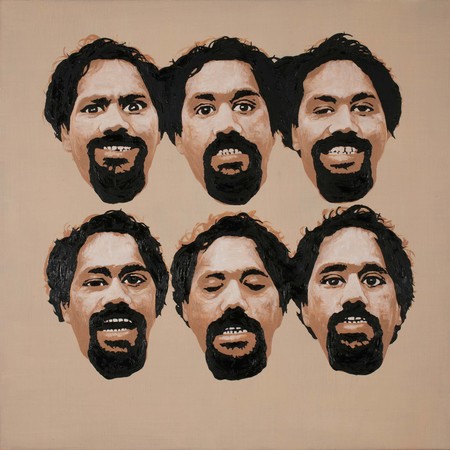

Jon Jeet Me Myself and I, a Commodified Mokomokai 2013. University of Canterbury Art Collection. Reproduced with permission

On the other side of town, Tongan artist Kulimoe’anga Maka uses a traditional method of producing Ngatu ‘uli (an elite form of tapa making). Kuli has won numerous awards and was the 2009 Macmillan Brown Artist in Residence. He is also one of thirteen artists in Pataka’s 2014 exhibition Tonga ‘i Onopooni: Tonga Contemporary, curated by Nina Tonga, now touring galleries nationwide.

Painter Teina Ellia, of Cook Island heritage, lives in Rāpaki and experiments with mixed media to explore ‘the autobiographical potential and possibilities of painting’.1 A Dunedin graduate, Teina participated in Dunedin School of Art Gallery’s 2012 Pasifika Cool, curated by Graham Fletcher and Victoria Bell, and in a follow up 2013 exhibition, Art in Law IX—Pasifika Cool Remix, curated by Peter Stupples.

Samoan printmaker Josh Bashford lives in Little River and produces woodcuts that relate his experience of faith, family and nature. Taking guidance from artist Fatu Feu’u, he has developed a deeper relationship with his Samoan heritage. Josh exhibits locally at the Little River Gallery and also in Auckland and Samoa.

Jon Jeet, of Fijian, Māori and Indian heritage, has two aspects to his practice: one loosely based around portraiture, the other comprising interactive art-making through workshops, public drawing and pounamu carving. Jon describes his portraiture as being ‘ethnocentric without bathing in sentimentality, or preaching the cultural revival movement’.2 He exhibits at the Eastside Gallery and was part of Minotaur, a 2014 group exhibition curated by Warren Robertson.

Multimedia artist Nina Oberg Humphries, of Rarotongan heritage, participated in Drowned World, curated by Daniel Satele, an online exhibition launched in December 2014, accompanied by performance at the Physics Room. Her work explores ‘cultural tradition and popular culture to create a visual language which represents me and hopefully others as a second generation New Zealand born Pacific Islander.’ 3

The future of Pacific art in Christchurch lies with our youth, and how they choose to acknowledge the voice of their ancestors.

With the resonant awakening of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, the city’s cultural enthusiasm has been revived. Although historically Pacific artists have been poorly represented by the Gallery, the reopening exhibition featuring Lonnie Hutchinson’s spectacular cut-out Sista7, and the reappearance of Pacific works from the collection, coupled with the Gallery’s new mantra ‘Art makes me’, indicates new energy from curators and staff for a more open engagement with Pacific art.

There are other positive signs. The reinstatement of the Macmillan Brown Pacific Artist in Residence programme and possible teaching opportunities for Pacific art historian Dr Karen Stevenson, also bodes well for Pacific art in Ōtautahi. Fika writers plan to perform new work and publish a second anthology, Faultline Poetry Collective, and the reopening of CoCA, means our visual artists and curators may have another opportunity to exhibit within the four avenues.

Within the Pacific arts community itself there is a greater sense of urgency around the creation of a more cohesive vision for the future of Pacific art in Ōtautahi. This was borne out by the Christchurch Pasifika Creatives Fono in 2015. While acknowledging the need for better networking and community support across the sector, the immediate result of the Fono was a call for new Fika members and creation of a Christchurch Pasifika Creatives Facebook page to keep our fragmented arts community informed.4 Every like is an affirmation.

So will 2016 be a year of ‘more’ for our Pacific Community? More art, poetry, music, theatre and exhibitions; more Pasifika creatives creating, engaging with social media and building relationships with mainstream institutions? Will there be more than a handful of Pasifika visual artists living in Christchurch and more people wanting to engage with Pacific art and cultural events? The future of Pacific art in Christchurch lies with our youth, and how they choose to acknowledge the voice of their ancestors. Will they feel the ongoing pull of the collective and understand the continued relevance of their Pasifika heritage? And will they find representation within our local arts framework?