The hungry gap

Audrey Baldwin. Photo: John Collie

We invited artists, academics, city makers, curators, health specialists and gallerists to comment on the challenges and opportunities for the arts in our city and what art can contribute to the future of Christchurch.

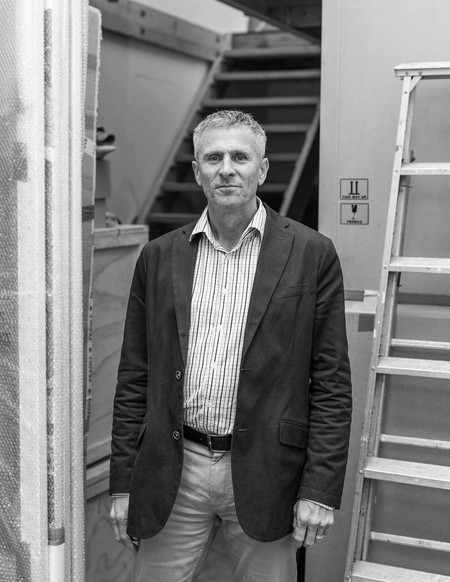

Philip Aldridge. Photo: John Collie

Philip Aldridge

We are good at catastrophe in the arts. The cataclysm might be a natural disaster, the crash of 1929 or fin de siècle decadence. The reaction might be community singing, the age of jazz or an Oscar Wilde. It’s simply the human condition. Show us an extreme and there will be an artistic reaction.

So it has been in Christchurch. Catastrophe has become defining for us as a city and created an artistic movement that will continue. Not because of blueprints or grants, although they may help, but because the gauntlet that nature threw down to Cantabrians—and humans’ inadequate response—continues to demand an artistic defiance.

The silt that Ma Nature shook off the river bed will take many decades to settle. We know that it will be a long haul to redefine the physical environment and we must brace ourselves that not all the battle scars have been inflicted yet.

So be it. We are changed. And we will change again. We must never settle. It ain’t over yet and that fat lady is still far over the horizon. And that’s not a bad thing.

Philip Aldridge is chief executive of the Court Theatre and chairman of BNZ in Canterbury.

Audrey Baldwin

The earthquakes stripped many artists and institutions of their familiar surroundings; however, I feel that we have met the challenge and benefited from opportunities unavailable before. We’ve grown stronger from our tragedy, producing a vibrant arts community that I hope will keep growing and self-seeding.

The arts and the communities involved with them have demonstrated a spine of steel and have encouraged people to remain in Christchurch, to stake a claim and make this city worth staying for. Art has acted as a salve for wearied souls; it has offered a motive to venture out over rubble-strewn sites and crooked footpaths—a reason to navigate ever changing street layouts and tackle road cone rally-tracks to witness and be a part of something transformative.

Christchurch artists have learned to be flexible, innovative and determined in a landscape that often operates outside the bounds of logic. The Social, a collective of Christchurch artists, saw me and many other recent graduates making work in public spaces such as the Re:Start Mall and various vacant lots in the CBD. From Liv Worsnop’s transformation of a Manchester Street demolition site into a Zen garden, to Tessa Peach and Heather Hayward holding a soup banquet for over 50 people along the tram tracks in Re:Start; surreal and ambitious projects have energised, inspired and surprised locals and visitors alike.

I see art as a key feature in shaping the future of our city. It’s an element necessary to help people through the transitional stage and beyond. The arts are key to creating a thriving, cultured, exciting city that consistently has more to offer.

Audrey Baldwin is an artist and arts enabler who calls Christchurch home. She curates First Thursdays Christchurch, jointly coordinates The Social with Gaby Montejo and is headmistress of the Christchurch branch of Dr. Sketchy's Anti-Art School, among other adventures.

Sally Carlton (left) and Suzanne Vallance (right). Photo: John Collie

Sally Carlton and Suzanne Vallance

Temporary art projects have brought colour, fun and life to Christchurch’s post-earthquake central city, positively impacting those involved as well as passers-by. These projects offer an alternative approach to orthodox rebuilding and renewal processes, challenging us to reflect on the importance of resourceful, experimental and imaginative urban environs.

Especially crucial to urban environments is inclusivity, and art can play a key role in incorporating, showcasing—and ultimately championing—diversity. Consciously attempting to fulfil this role, some temporary use organisations have actively solicited the involvement of those who rarely feature in formal recovery programmes such as marginalised or minority groups, enabling them to participate in project design and creation. Yet temporary use and other public art will only prove truly inclusive once the initiators of these projects themselves hail from non-dominant backgrounds. With its tradition of post-earthquake community action, Christchurch’s arts scene will hopefully continue to develop to accurately reflect the city’s contemporary identity and rich socio-cultural diversity.

Dr Sally Carlton's research interests include social impacts of, and community responses to, the earthquakes. Having completed post-doctoral studies at Lincoln University, she works for the Human Rights Commission.

Dr Suzanne Vallance is a senior lecturer in the Department of Environmental Management at Lincoln University with interests in sustainability and resilience.

Lucy D'Aeth. Photo: John Collie

Lucy D’Aeth

Art is good for health. Making art. Seeing art. Numerous studies support this[1]. As Christchurch regenerates, arts can play a fundamental role in creating an environment which supports all citizens to live healthy and fulfilling lives.

Since the earthquakes, art has been a means to expressing grief and finding healing. In a city full of cones and potholes, formal and informal public art has been an unpredicted joy of transitional Christchurch. From a public health perspective, we know that the environment plays a significant role in whether people can lead healthy lives—if our city is safe, clean, accessible and beautiful, the population will be healthier and happier.

The five ways to wellbeing: give, take notice, keep learning, connect and be active2, are scientifically proven steps to feeling good and functioning well. Participation in and engagement with art in all its forms enables people to practice these five ways. Prescribing an arts course to treat people suffering anxiety or mild depression can be as effective as prescribing drug treatment.

A city which invests in public art, in participative arts and arts education will see benefits in both population health and financial prosperity. As Christchurch people encounter a vibrant arts scene, as local artists of all kinds are able to thrive, as all Christchurch people feel inspired to explore their own inner artists, the health of the city will be restored.

Lucy D’Aeth is a public health specialist with the Canterbury District Health Board. Since the earthquakes, much of her work has focused on population wellbeing promotion.

[1] For a good local overview of the evidence see Susan Bidwell’s paper ‘The arts in health. Evidence from the international literature’, March 2014, Pegasus Health.

[2] Five ways to wellbeing were developed by NEF (New Economics Foundation) from evidence gathered in the UK government's Foresight Project on Mental Capital and Wellbeing.

Jessica Halliday. Photo: John Collie

Jessica Halliday

Since 2011 the arts in Christchurch, and many of those involved in the arts, have proved to be fleet-footed, agile, clever, caring and socially engaged. Our understanding and expectations of both art, and also the city, are broadened and now inform each other more closely.

The role of the arts post-quake demonstrates how important it is for a city to have or involve aesthetic aspects. In fact, the city really is an aesthetic cultural product in the broadest sense: the city affects our senses, our bodies, our minds, our relationships, and emotions. If we continue to see city-making as an art and art as part of city-making, we will grow a city in which simply being here can be more wonderful, rather than being something to endure.

Christchurch isn’t just an economic instrument or a complex system that meets purely functional needs. Christchurch should be a place that feeds us aesthetically, intellectually and socially; art is necessary for that.

Jessica Halliday is co-director of Te Pūtahi - Christchurch centre for architecture and city-making; and of FESTA, the Festival of Transitional Architecture.

Aaron Kreisler. Photo: John Collie

Aaron Kreisler

Looking at art since the earthquakes, my major concern would be that relying on art to memorialise our recent history isn’t enough. We have got to give artists space to do things beyond the feel-good. Art operates by not fitting into the system. You can’t zone art into a particular space. Where are the places for artists to make truly exceptional, challenging artworks?

People don’t question quality around material goods. But as soon as you apply quality to art you’re accused of being a snob. We started the rebuild by discussing quality of design, architecture and urban flow. But now people are saying, no, we just need to get it done, we’ve got the money now, if we don’t use it we’ll lose it.

We put money aside for an art project, bureaucracy absorbs most of the funding and then we shoulder tap an artist and say: ‘Can you do this?’ But we’ve already set all the terms. The project needs to be culturally aware, historically connected, place conscious... Projects go through so many hands that ideas are over processed. Then we ask an artist: ‘Can you put your name on this?’

There has got to be a way to not completely bureaucratise the regeneration of this city. We have to start to bring artists to the table. Artists bring a different set of values which will make more interesting work and change the process itself. We have to be willing to let go of a certain amount of control. And we need to respect that the people doing the work are taking always the greatest risk. The problem is we think that the greatest risk is the money.

Aaron Kreisler is head of the School of Fine Arts at the University of Canterbury and was formerly curator at Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

You can read an interview with Aaron Kreisler on this topic here.

Kim Morton. Photo: John Collie

Kim Morton

Art can open up doors that trauma and grief have firmly closed. The deepest impact is made when we have opportunities to participate in arts—rather than be an audience for others’ work—and through this, to connect with others. Artists can feel anxious when they first join shared spaces but once they feel at home they see possibilities—printmaking, sculpture, drawing, painting and much more—a creative spark is ignited. Isolation evaporates, replaced by a sense of belonging to a creative community which is welcoming, inspiring and encouraging.

As the city is rebuilding, creative arts give us a space to rebuild our lives so that we can be active participants in the regenerating city. Using art as a point of connection allows everyone to help shape our new city—including the hidden people who don’t leave their houses, and who don’t feel they have a voice.

Just as the earthquakes were a catalyst for change, art can also transform our lives. Let’s not revert to the way things were before the earthquakes. Let’s look beyond the CBD and support the villages that make up Ōtautahi to get creative together. Art represents the human dimension of the city as it is re-made and our city’s manifesto should enshrine the vital role of art in the wellbeing of our communities.

Kim Morton is the leader of Ōtautahi Creative Spaces, an arts and wellbeing initiative, which is based at the Phillipstown Community Hub and is expanding to other sites in Christchurch East.

Jonathan Smart. Photo: John Collie

Jonathan Smart

This might be an odd thing to say post-quake, but it seems to me that the big challenge for art in the city today and of the future is the same as it always has been—how to overcome a lack of opportunity.

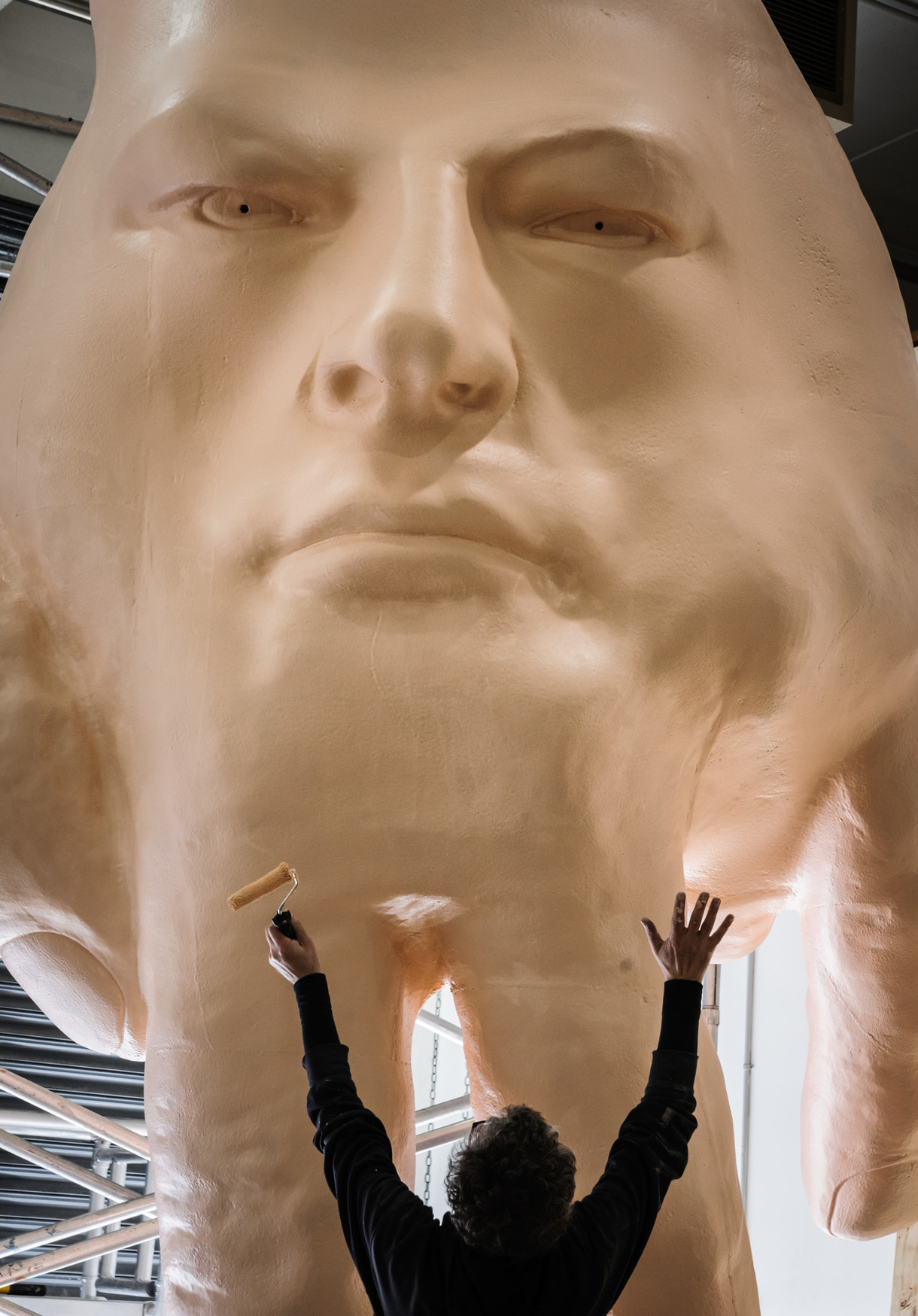

We know that good art presents something energizing for people, something that stops us in our tracks and gets us thinking. The new Gormley work Stay will do this, I think.

But winning such opportunity is never easy. The All Blacks talk about ‘earning the right’ (for this and that), but they get to play quite a lot. As a gallerist in Christchurch for 27 years now, I look for opportunities for our best artists every day. And in the public domain, in the foyers, on the walls, or outside the buildings of our future city for example, there is precious little will to allow artists any opportunity to play.

Sadly, I think this is a lack of daring and trust, a crisis of commitment and imagination, as much as it is a challenge to the purse. Still, it is my job to prospect and dream of making the possible happen.

Jonathan Smart is a gallerist and angler who runs Jonathan Smart Gallery, where for many years he has shown and sold contemporary New Zealand art.

Martin Trusttum. Photo: John Collie

Martin Trusttum

There was a groundswell of collective energy following the Canterbury earthquakes; individuals and communities forged alliances, which led to a great deal of productive activity. And the arts were not simply an example of this phenomenon but a catalyst for it. People believed art could make a difference; bringing people together to share, to grieve, and to begin to heal. Consequently, the arts and artists received support from industry and corporates, institutions and organisations on a scale that hadn't been seen before in Christchurch. Art galvanised the people of Christchurch at a time when the only other conversation was loss.

But as time passes and our city slowly regains a more solid form, the once shared collaborative objectives are facing the perils of fatigue, habit and pragmatism. For the local arts community the challenge is to nourish the unique enthusiasm that hatched in 2011 and to keep the local community engaged. The arts might seem less important in a hierarchy of needs than infrastructure, but I don’t believe it’s a competition. The arts are very rarely at the expense of infrastructure in our modern environment. People need a rich network of associations and links to feel happy and safe—to thrive. We clearly need to meet our physical needs, but as human beings, we have emotional needs too. Art, in the broadest sense, goes a long way towards expressing and satisfying this emotional requirement.

Artists appropriate influences, ideas and concepts from any source that seems relevant and in so doing develop, extend, and reframe conversations over time and distance—conversations that affect all of us and enrich our lives. Putting the arts at the centre of any debate about the city's growth is part of a long-game plan and is the hallmark of a mature culture. We need to be thinking 50 years into the future, 100 years even, and asking ourselves: what sort of city do we want our children’s children to live in? If we do this I believe we will come to see that the arts will need a seat at the planners’ table. Today.

Martin Trusttum is a project manager for the arts. Recent roles include managing development and operations of ArtBox, a relocatable gallery space designed and built using a bespoke modular system, and Ōtākaro Art by the River, a public art project as part of Te Papa Ōtākaro/Avon River Precinct.

You can read an expanded version of this article here.

Gap Filler team clockwise from bottom left: Ryan Reynolds, Rachael Welfare, Bec May, Simon Gurnsey, Anita Parris, Rosaria Ferguson, Sally Airey and Richard Barnacle. Unable to be present were Coralie Winn, Hannah Airey and Trent Hiles. Photo: John Collie

Rachael Welfare

After the earthquakes, the loss of public art spaces and galleries was quickly felt in the city; the value of art was recognised more than ever when it was seemingly lost. Whilst Gap Filler and other similar organisations made significant physical contributions to the public art scene, perhaps more importantly they helped to provoke conversations about, or subtle shifts in, what art means.

What we have seen as an organisation is a huge opportunity to try new things, nurture initiatives and create without boundaries. Projects such as the Pallet Pavilion and Dance-O-Mat are perhaps not immediately identified as art; but as creative and emotive outlets that are beautiful as well as provocative, they sure fit our definition!

The huge variety of public art that sprung up after the quakes became a source of colour and hope in a city deprived of both. It created a shared sense of purpose and became a way to reclaim space, show support and give people a voice. The conversations have continued to evolve in recent years; more than hope and healing, art has become a way to voice defiance and frustration. The sense of shared purpose and community remains—and art is created not just by artists but by anyone with something to say.

As a result, the Christchurch public is more open than ever to a broad definition of art, and is appreciative not only of the physical outcomes but also of the purpose, energy and processes behind the acts of creation. These are the legacies of the arts in post-quake Christchurch—and long may they continue.

Rachael is the operations director of Gap Filler. Gap Filler is a creative urban regeneration initiative that aims to innovate, lead, and nurture people and ideas. Their projects catalyse conversations about city-making and urbanism in the 21st century, whilst being engaging, quirky and fun.