The wisdom of crowds

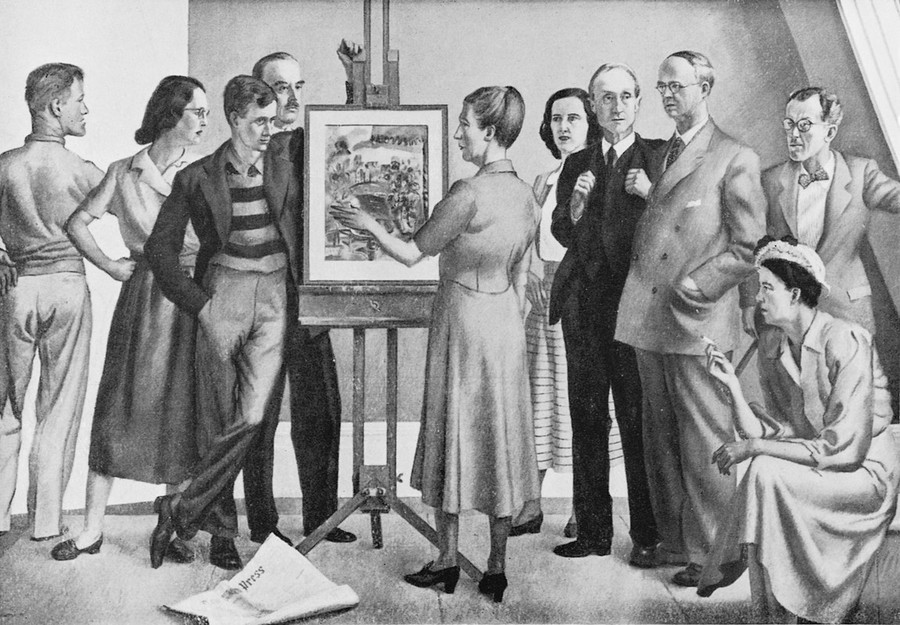

W.A. Sutton Homage to Frances Hodgkins 1951. Destroyed. Artist Bill Sutton, then a young lecturer at the art school, registered his protest at the rejection of Pleasure Garden by painting a large composite portrait of Hodgkins's supporters grouped around the work. It was an imaginary meeting; and likely to have been based on Henri Fantin-Latour's A Studio in the Batignolles (Homage to Manet) (1870), now in the collection of the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. At the centre of the image is Hodgkins and a young Colin McCahon. In the foreground, a discarded copy of The Press lies crumpled on the floor. Sutton's painting was damaged beyond repair a few years after it was painted, but photographs of the work remain.

In recent years, crowdfunding and crowdsourcing have become big news in the arts. By providing a funding model that enables would-be-investors to become involved in the production of new works, they have altered traditional models of patronage. Musicians, designers, dancers and visual artists are inviting the public to finance their projects via the internet. The public are also being asked to provide wealth in the form of cultural capital through crowdsourcing projects. The Gallery has been involved in two online crowdfunding ventures – a project with a public art focus around our 10th birthday celebrations, and the purchase of a major sculpture for the city. But, although these projects have been made possible by the internet, the concept behind the funding model is certainly not new. The rise of online crowdfunding platforms also raises important questions about the role of the state in the funding and generation of artwork, and the democratisation of tastemaking. How are models of supply and demand affected? Does the freedom from more traditional funding models allow greater innovation? Do 'serious' artists even ask for money? It's a big topic, and one that is undoubtedly shaping up in PhD theses around the world already. Bulletin asked a few commentators for their thoughts on the matter.

When Michael Parekowhai’s bronze bull – Chapman’s Homer – goes on display, its label is a crowded affair. It includes the names of twenty-seven corporate donors and private individuals, as well as ‘1,074 other big-hearted individuals and companies’ who gave money to purchase the work for Christchurch. Chapman’s Homer caught the public imagination as a symbol of the resilience of local culture when it was exhibited amid the devastation of the Christchurch earthquakes; a successful crowdfunding campaign kept it here. While online crowdfunding for art and culture is a recent phenomenon, the practice itself is not. Historical antecedents cited by the US funding platform Kickstarter include Alexander Pope, who generated 750 subscribers for his translation of Homer’s Iliad in 1715; Mozart, who crowdfunded the performance of three piano concertos in Vienna in 1784; and the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in 1885, which was paid for by more than 160,000 New Yorkers after a fundraising campaign run by Joseph Pulitzer, mainly through individual donations of less than $1 apiece.

Christchurch Art Gallery has a long history of crowdfunding. Many of the Victorian paintings and sculptures in the collection were acquired by the Canterbury Society of Arts (and later transferred to the Robert McDougall Art Gallery) from the 1906 New Zealand International Exhibition with a fund of £2,442 raised from council members and local businessmen. A ‘group of citizens’ purchased Dame Laura Knight’s Les Sylphides from the Back of the Stage in 1935 after an exhibition of her work toured New Zealand; Jonathan Mane-Wheoki persuaded a group of ex-Christchurch students each to chip in £5 to buy Karel Appel’s Personnage Jaune in London in 1973. Other groups came together over the years to acquire works for the city’s collection by Raymond McIntyre, Louise Henderson, Eric Lee-Johnson, Archibald Nicoll, and Marté Szirmay, among others.

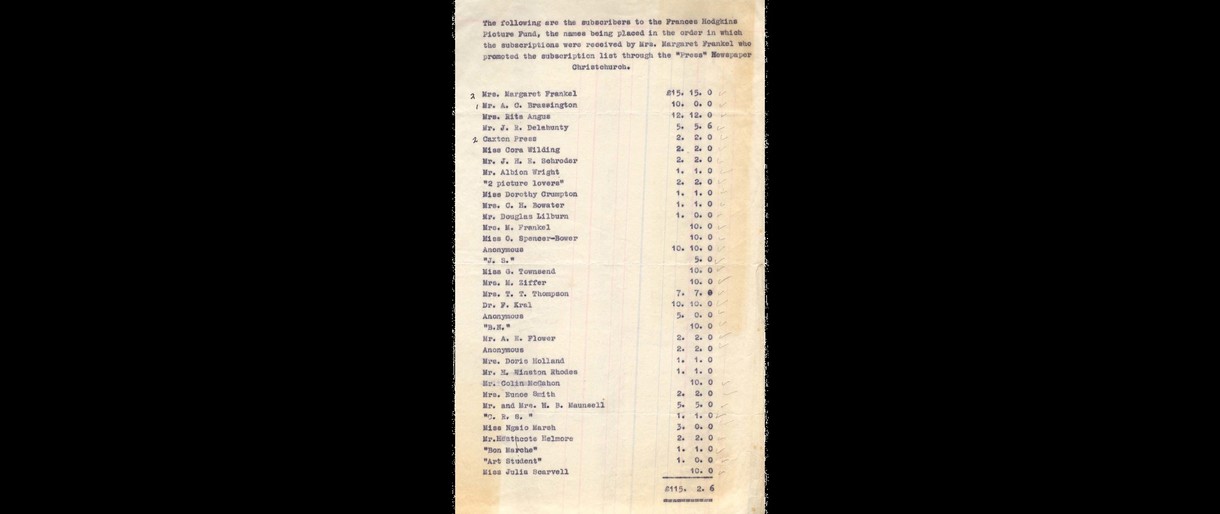

Controversial crowdfunding campaigns were behind the acquisition of two well-known modern works in the collection. The long list of subscribers to the picture fund for Frances Hodgkins’s Pleasure Garden in 1949 included artists Rita Angus, Olivia Spencer Bower, Doris Lusk and Colin McCahon; led by local potter and painter Margaret Frankel, they battled for many months to have the work accepted into the city’s collection. Frankel wrote that ‘it had not been at all difficult to find subscribers ready and willing to give money for this painting so that the Robert McDougall Art Gallery might have at least one picture by this famous New Zealander.’ What had been difficult was the heated argument over the merits of modern art (later described as Christchurch’s ‘Great Art War’) which took place at public meetings and in the pages of the newspaper.

History repeated itself in 1960, when the gift of McCahon’s work Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is – funded through a public subscription organised by the city’s librarian, art patron Ron O’Reilly – was initially refused by the director of the Robert McDougall, W.S. Baverstock, who had been instrumental in the rejection of Hodgkins’s work a decade earlier. The work was finally accepted in 1962, and is now regarded as one of the Gallery’s most important modern paintings.

Lara Strongman is senior curator at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Crowdfunding is both an opportunity to increase the role of individuals in supporting creative projects and a potential threat to the democratic investment of the whole of society in culture and the arts. This apparent paradox is older than the internet or crowdfunding: every time a voluntary organisation supports an institution or offers a service that amounts to a public good, it means that local and national government don't have to provide; and if they don't have to provide, then someone might argue that it's not their place to do so.

When it comes to crowdfunding, we have heard the argument already. In the United States, where the money raised by Kickstarter alone has long-since surpassed the disbursements of the National Endowment for the Arts, the Republican candidate at the last presidential election pledged to end Federal contributions to the fund; whereas in the Britain of new austerity and the Big Society, the role of the Arts Council established by Keynes in 1946 is routinely questioned. Taking part in a debate hosted by The Economist, Adam Smith Institute researcher Pete Spence declared that 'The dead hand of the state doesn't have much going for it – we should put it to rest and embrace the messy, diverse, vibrant tapestry of commercial funding.'

The rhetoric is familiar, and the key word is 'commercial'. Although major institutions such as the Louvre have used it to secure funding for permanent exhibits, crowdfunding in the arts has mostly been successful to date as a mechanism for pre-selling, whereby individuals might invest in a project in exchange for a book, CD, DVD, print or concert ticket. But the arts aren't the sum of consumer products, including live performances or exhibitions, nor is commercial success the only measure of an artist's work. Crowdfunding is often said to democratise patronage and investing, but art is a public good, and ensuring that the state remains committed to its support means above all protecting a collective democratic stake. Our methods for determining artistic value may be imperfect, but this doesn't mean that we should defer the responsibility of making those decisions solely to the market, or to the people with enough disposable income and time on their hands.

This is not to deny the value of crowdfunding, which lies precisely – and it is no paradox – in creating more opportunities for the public to participate in those decisions; in extending and deepening the commitment we make as a society to activities that cannot be reduced to a cost-benefit analysis, yet define us.

Giovanni Tiso is an Italian writer and translator based in Wellington. He has written about media and politics for a range of publications including The New Inquiry, The New Humanist and The Guardian, and is a featured writer for the Australian literary journal Overland. He blogs at Bat, Bean, Beam (bat-bean-beam.blogspot.com).

Crowdfunding is a new take on an old method for funding the arts: patronage. Count Ferdinand von Waldstein earned lasting fame by his early sponsorship of Beethoven. While patrons supporting the arts through Kickstarter can hardly expect similar name recognition, they can similarly enjoy a sense of part-ownership of the final production.

Arts patronage was typically, and remains, the domain of the wealthy. Smaller patrons could never really be sure how much difference their contributions made. Consequently, donations can suffer from what economists call a public goods problem: because everyone can benefit from a work when it is produced, it is often best to sit back and wait to see whether the work might be produced without your contribution. And so arts organisations provide special bonuses for members of their affiliated groups of supporters.

While this comes some way towards solving the public goods problem, crowdfunding alternatives provide a more direct approach: no donor is charged unless the project has enough pledged support to go ahead. Each donor can then feel part-ownership of the project. Because of the donor's support, along with that of like-minded others, an artist could make something new and beautiful – as judged by the donor. The New York Times reported in January that the traditional fine arts have some of Kickstarter's highest success rates.1

The public goods problem remains where some would-be supporters delay pledging in hopes that the threshold is reached without their contribution. Clever crowdfunding initiatives can mitigate the problem by providing bonuses to early pledgers, like signed tokens from the artists that can be produced at low cost but are of high value to supporters as it enables them to display their affiliation and support.

Even better, arts organisations can use crowdfunding mechanisms to gauge support for the different initiatives they might undertake. A gallery could propose commissioning several different works; patron support through PledgeMe would determine which were commissioned, and supporters could receive small versions of the commissioned work in acknowledgement, from pins through prints.

PledgeMe supporters of a [hypothetical] Christchurch Art Gallery commission of a new painting (by an artist like Jason Greig, for example) would hardly earn Waldstein's fame. But, a supporters' limited-edition lithograph of the newly commissioned work could be fame enough for many supporters – including me.

Eric Crampton is head of research with the New Zealand Initiative in Wellington. From 2003 to 2014, he lectured in Economics at the University of Canterbury.

'The crowd' is now also capable of creating value for an institution directly, through their participation rather than their donations. But successful use of this social currency requires us, paradoxically, not to think of 'the crowd'. Instead, we must work to ensure that the act of a single participant offering a single contribution is as meaningful, effortless and joyous as possible.

Members of the public arrive already filled with enthusiasm for our cultural heritage institutions. Tapping into that reservoir of goodwill requires empathy as much as technical savvy or financial resources. Without an understanding of the motivations of potential participants, even the most generously funded project has little chance of receiving their time and attention. The key questions are: What things in our collections do they find most interesting? What makes them want to contribute something to those collections? And, crucially, what makes them want to continue to do so?

Some collections are more charismatic than others, in that the stories that they tell are entertaining and readily understood. It's no accident that the most successful project of this type that I've worked on was a collection of restaurant menus. Anything related to family histories, local communities/iwi, maps, beautiful pictures – and yes, food – is always innately interesting to people.

Software interfaces for crowdsourcing are crucial to their success, and need to be relentlessly tested and edited. When evaluating a design, I am constantly looking for its 'core gesture'. An early prototype that might require four or five steps to get anything done must be revised until it's ground down to one. This is the hard work of design: the sanding-off of all of the sharp edges until the participatory flow is as free and easy as possible. If an interaction is the least bit difficult to get through once, forget ever asking people to repeat it over and over.

Crowdsourcing appeals to participants' better nature. When as little as ten seconds of 'micro-volunteering' can create some new value, both institution and volunteer benefit. While editing, correcting and adding to a collection, a participant gains a deeper knowledge and understanding of its inner workings than she could ever get from a simple Google search. It's a very active form of learning. The sense of ownership this engenders has the side effect of keeping the quality up; I commonly hear from managers of these projects that the bad input or vandalism they initially feared turned out to be almost non-existent.

When everything comes together, though, the act of contributing becomes its own reward. That same simple thing that makes people spend hours playing Candy Crush on their phones – a satisfying response to a simple gesture – can be harnessed in the service of improving a part, however small, of our shared cultural heritage. And the double good feeling that that instils in the participant will make her want to come back often, and to share her experience with others.

Michael Lascarides is the manager of the National Library online team at the National Library of New Zealand in Wellington. Prior to joining the NLNZ, he managed the web team at the New York Public Library, where he helped create a number of successful crowdsourcing projects. He is a contributor to the recent book Crowdsourcing Our Cultural Heritage (2014, Ashgate Press, edited by Mia Ridge).

Arts philanthropy is about participation. Being part of it, close to the action, this is what excites people to donate to the arts. Crowdfunding is fast philanthropy in a modern context. Artists that engage with donors understand the potential for deeper relationships when they share their creative process.

At Boosted we provide a simple plan that significantly increases an artist's chances of success with online fundraising. As part of the plan we advise artists to invite audiences into their studios, to collaborative sessions and on research trips during their campaigns. Audiences that experience an artist at work become invested and sometimes lifelong supporters.

I am excited by the potential for crowdfunding to inspire artists to increase engagement with audiences; to open up the process of creation as part of the experience for audiences in the final work. This won't suit all artists, but for some it could be an enriching part of their process.

Eliot Collins launched his Boosted campaign on Auckland's waterfront with the opportunity for people to paint the first strokes of his mural. He had a ceremony to hoist a flag and a party. Eliot said 'I want to reintroduce the romance of the waterfront to the people of Auckland'. Boosted helped Eliot create engagement in his message and investment of hearts, minds, and wallets in his project.

Opening up the creative process and/or providing ways for audiences to help artists create work provides a new level of artistic risk. The deeper the relationship with the audience, the less financial risk there is to reach a crowdfunding target. Invested audiences donate.

Crowdfunding has the potential to dynamically increase the level of knowledge people have about the arts, but it does not turn the public into curators. The relationship between donor and artist is one on one; it is very rare for donors to visit a crowdfunding site to choose between projects. The artists with the best philanthropic strategies are the ones that reach their targets.

Public engagement in the funding of arts projects has the potential to increase government and civic funding. Projects that are funded on Boosted demonstrate innovation in raising funds and a high level of engagement with audiences. Artists that achieve targets on Boosted can increase the confidence of funders by providing tangible evidence that audiences care.

We can't wait to see artists use Boosted to create work with audiences. The potential for audience interaction to become integral to the art experience is one of the most exciting things about the future of crowdfunding.

Simon Bowden is executive director of the Arts Foundation and creator and trustee of Boosted.

Let's start with taste making, for I'm not sure that public institutions do so much of this these days. Private collectors have their own ideas and, in a culturally-active city, dealer galleries, artist-run spaces, academics and auction houses also play a role; advertising, magazines and journals further shape tastes (I prefer to think of them as multiple and diverse) as well. Relatively speaking, art galleries in New Zealand are less able-to-buy than an active range of private collectors.

Public galleries certainly confirm and maintain a record of what's visually significant at a given time. And we operate within a broader market place; dealer galleries may discount works for art museums; artists will list collections they are in, public as well as well-known private collections. But relative to some, our means are limited.

It's part of our job to be aware of market values and negotiate appropriate prices for collection items. But we work with an eye for the longer term and it's important to know when a collection will be so enhanced that it's necessary to pay top price for a given work, to wager that this specific investment will pay off in terms of cultural understanding and community pleasure. The price might seem high at the time, but a gallery's reputation is judged on what it collects, not what it fails to acquire. Others trust our judgements – and we anticipate market catch up.

Now to sources of funding. There's a big difference between receiving public funding and being fully funded. About three-quarters of Christchurch's operational funding is secured via the ratepayer base and we could not maintain the city's collections nor open to the public without this reliable core funding. So Gallery staff are expected to maximise an income stream in support of what we do – more than the current allocation from rates is needed to maintain the quality and relevance of what we present.

Our situation is worsening, however. In this city with multiple priorities, the new long-term plan proposes halving acquisitions funding from July 2015. Our task of representing this time and ensuring the city's collection remains nationally significant continues. We'll become even more reliant on our Foundation raising money from private individuals for at least the next four years.

This institution needs to be increasingly clear about the importance of our role as visual archivists of a place, our histories and our cultures. We know how much good art really matters – we've seen how it shapes a community, inspires us, make us laugh, helps us to think and reflect. Collections like ours (and the exhibitions through which we interpret it) are a key means of ensuring our community respects the past, debates the current and is given tools to imagine the future.

This Gallery, its partners and friends, will work energetically to ensure all our key tasks are supported to play their part. The means may change from time-to-time, but the fact of fundraising is not new. Various mechanisms are used, with online crowd-funding a recent innovation. We know from experience that this takes careful planning and a heap of personal energy. You couldn't do it often.

Is it me, or does our role as taste-maker suddenly seem a bit inconsequential?

Jenny Harper is director at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū.