Living Archives

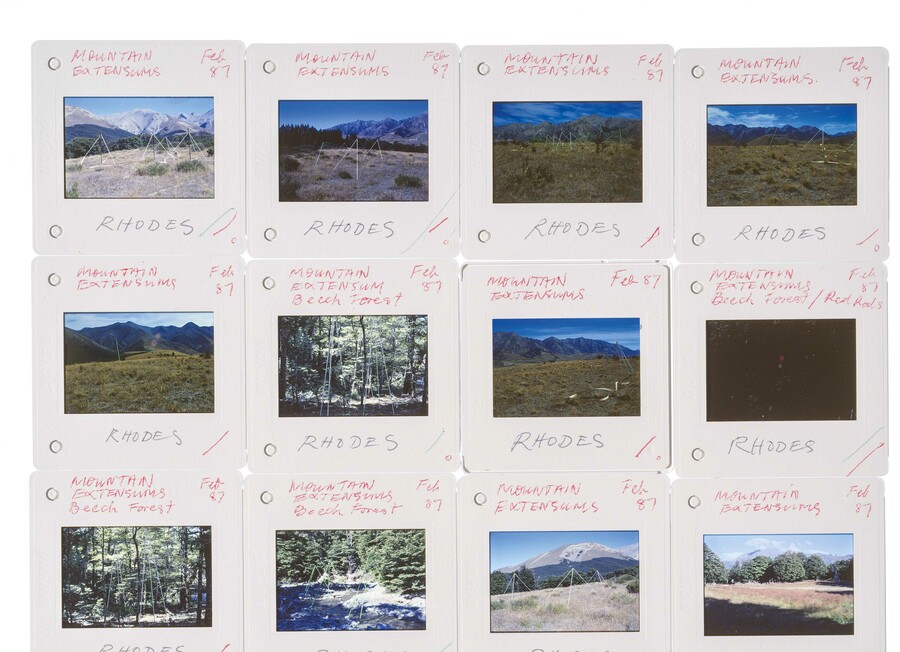

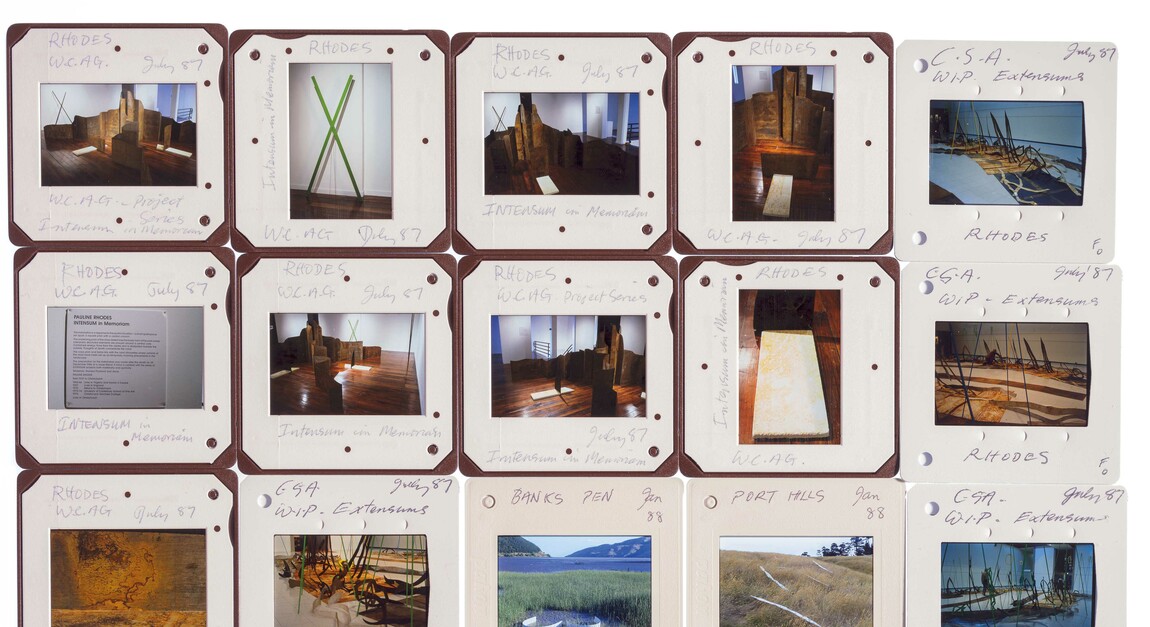

A selection of archival slides by Pauline Rhodes, 1987–8

Archives are collections of knowledge used to tell stories about artists and history. By drawing on the legacy of art historians Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, Julie King and Karen Stevenson, Living Archives focuses on intergenerational relationships, artistic lineage and creative networks. Gallery librarian and archivist Tim Jones and curator Melanie Oliver sat down to talk about archives and art history as they prepared for this exhibition.

“The traditional view of an archive is now being increasingly dismantled.”

Melanie Oliver: I think it’s interesting Tim, that when you go on holiday, you sometimes make sound recordings instead of photographs. I wondered what that says about the value of different forms of document and memory?

Tim Jones: Well, a sound is often more evocative than a photo isn’t it – the swish of the tube door closing, frogs in the dusk somewhere in the South Pacific. Neither of those can be photographed. So you’re right, different media can stimulate memories and can achieve different things in your mind. And sound is now such an easy one to capture.

MO: It’s also a form that sits uncomfortably in the archive at times, in terms of oral histories and waiata, sound art or performance. I think that cuts to the heart of what we’re trying to do with our exhibition as we think about what an archive is, or can be.

TJ: Archives are traditionally bits of paper from various places – even books fall into that category – but other media demolish that simplicity, don’t they? The traditional view of an archive is now being increasingly dismantled.

MO: It’s become more porous. And necessarily challenged in terms of representation.

TJ: Not that it’s ever been straightforward, because of course archiving bits of paper is also rich with complexity and challenges and difficulties.

MO: Haphazard, I think, is how we’ve described it. It’s always partial – in parts and fragmentary, but also in terms of the perspective of who’s collecting objects or documents and why. That effects what makes it into the archive and what is left out, the inclusion/exclusion of the archive.

TJ: Plenty of people have wrestled with this problem! And it is accentuated because being included in the archive acts as its own privileging mechanism – once you’re in, you’re doubly recognised. As archivists we generally think about our roles as gatekeepers, we try not to be, but we inevitably are. We have our own tastes and prejudices and views of the world that we try to neutralise, often without success. The archives are their own living, breathing, organic entity. We think we’re running them, but in many ways, they’re running us.

MO: The other side of the coin is that as curators and art historians, we’re going into that archive and accessing the stories that can be told from those documents. The histories that we write from those materials are in turn informed by that bias, whether that’s in terms of a lack of visibility of queer voices, class distinction or diversity of culture.

TJ: Absolutely, and language. I’m nervous of the word bias because that suggests a sort of a deliberate malicious intent, but there is inconsistency, absence and incompleteness. There’s absolutely no question about that.

MO: The archive is seen as the truth, if you like, but it’s riddled with fiction, rumour and silence.

TJ: That is the problem; something written down, or recorded, can be entirely incorrect. So the big question becomes what is correct and what’s not, and even that’s tricky. But once something is in the archive, it’s treated as truth. And there are so many known examples of inaccurate information – ‘alternative facts’, to use a current phrase – becoming standard fare for curators to use and reuse. Even first-person narratives need to be treated with caution.

MO: I’ve tried to treat all material as having that complexity.

TJ: I think having an awareness of the absences and the inconsistencies is the only way you can proceed, otherwise you’re lost, aren’t you?

MO: I often think about the archival language, rules or systems, and how to disrupt these in order to better reflect society. Theorist Doreen Mende talks about the progressive archivist as being an “undutiful daughter”, knowing the archival language or law, but also believing in its futuristic power, manifest through conceptual disobedience.1 I hope there’s a bit of unruliness in this exhibition and trying to rephrase the archive, how we might be productively undutiful.

TJ: I think that’s how scholarship advances, by being disobedient to what’s gone before. Otherwise, you’re just saying the same things over and over again, aren’t you?

Material from the Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives

“We are definitely privileged to have both her donation of art and her archive, which speak to each other beautifully.”

MO: We structured this exhibition around three art historians who worked in Ōtautahi Christchurch and played an important role in telling the stories of art and reforming the art history of Aotearoa.

TJ: Selecting those three was in itself an act of archival privileging, part of the very process that we’re trying to undermine and disrupt.

MO: That was intentional though, and while still believing in the future potential of the archive. One of the art historians that we’re highlighting is Jonathan Mane-Wheoki.2 He taught art history at the University of Canterbury, was honorary curator of Māori art for Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū from 1992 to 2004, and then director of art and collections for Te Papa Tongarewa. Over his career, his focus shifted from Victorian art and architecture to recentring the art of this place, especially Māori art, architecture and contemporary art.

TJ: The other interesting thing about his career is that he straddled the two worlds of museology and academia, moving effortlessly between museum curator and academic and back again. That gives him an incredible breadth of experience in all aspects of art history – what’s being collected and what’s then being taught about those collections.

MO: He was a pivotal figure who inspired many others, and part of an art historical genealogy or network. For example, Buck Nin included Jonathan as an artist in one of the first exhibitions of Māori contemporary art, held at Canterbury Museum in 1966; Jonathan later conceived the 1999 retrospective exhibition of Buck’s work among countless other projects that told a distinctly Māori art history; Jonathan taught, curated, wrote, advised and encouraged other art historians, one of whom is the second art historian that we focus on, Karen Stevenson.3

TJ: The Pacific histories Karen concentrated on are a recent contribution to this institution, both in terms of collecting works of art and generating archival material that supports and elucidates those works of art.

MO: Karen has very generously given the Gallery fifty-seven works from her private collection so that ours can be more representative of the practices happening in Ōtautahi and across Aotearoa, and her own research archive. I love the story of how she met Jonathan. When she came to New Zealand from Los Angeles, Bottled Ocean was one of the first exhibitions that she saw. Then she was gifted a box of cuttings and notes by Jonathan, who said “you might like to take a look at this”. And that spurred her on to develop relationships with a range of Pacific artists and tell their stories.

TJ: We are definitely privileged to have both her donation of art and her archive, which speak to each other beautifully.

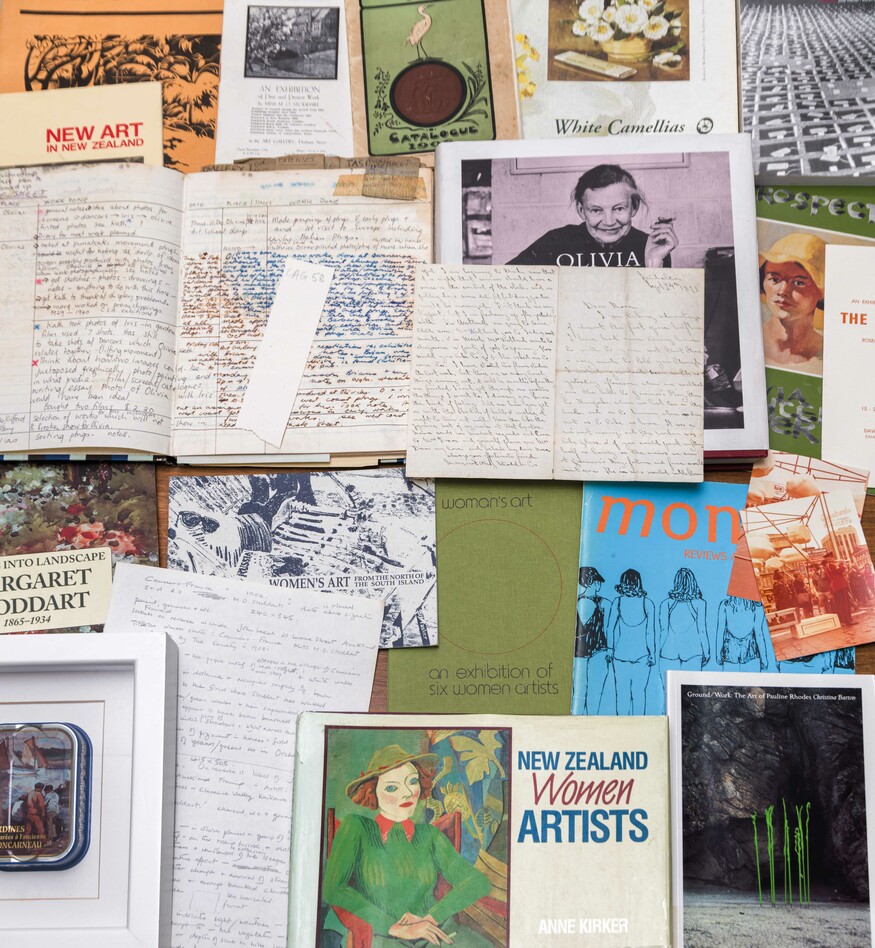

MO: The third of our art historians is Julie King,4 who was another much-loved art historian and lecturer. We have recently been donated her archive of teaching notes and her research into several of the artists that she wrote books on. So we have things relating to the processes of artists in the show, but we also have the processes of art historians.

TJ: We’re still organising Julie’s archive, which was given earlier this year, but it illustrates the breadth of her thinking and the connections that she, as an Englishwoman, had between Britain, France and New Zealand. The whole expatriate New Zealand experience and the women artists who had been underrepresented in the art history that she found when she came here.

MO: Looking out and looking in – we that see across Jonathan’s art history as well.

TJ: For all three it wasn’t just local history, it was where Aotearoa fits into world art history.

MO: A repositioning of us within a global discourse.

TJ: Julie did a lot of her research in the library here using other people’s archives – her research depended on their research. A lot of the material she worked with was incomplete, had been filtered by other hands and was not utterly reliable as evidence for whatever argument she was making. So she also wrestled with the archival problems that we do.

Material from the Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives

“We need to remember that stories can be told in all sorts of different ways – in objects, on bits of paper, on slides, on computer screens, and through music.”

MO: Others might have been tempted by a more creative or speculative approach. Another archival problem we touch on is around digital archives and impermanence. If something exists on Instagram, how does that become part of a record? Or a website – even that can be there one day and gone the next. We’ve included a Tumblr account, a now less fashionable platform, which illustrates the instability of digital.

TJ: This is a fundamental problem for archivists, a major issue that people are wrestling with. The National Library harvest websites, but more ephemeral things like Instagram or Tumblr or TikTok, even email, I don’t think have been grappled with at all. So there are two problems: the ephemeral nature of some of that material, and then also the technical problems of changing formats and obsolescence. Can you even open it or read it or understand it. But context is perhaps the third aspect there. One email tells you something, but you often need to know the chain of emails it was in to make any sense of it. Stripped out of that format or context it’s quite hard to understand. I’m sure we’ve all used the Internet Archive and been amazed by what they’re doing. But personally, I wonder about the sustainability as decades go by and more and more content is there. In this exhibition, we are at least highlighting it as an issue.

MO: I think collectivity is another archival issue – when something is made by more than one person, that creates a problem for the archive. How do you attribute or catalogue it?

TJ: Most of the archives that we have, and it seems to me most of the research that makes use of them, are based on individual artists. That’s how we organise the archive. And I’m not sure which comes first, the research need or the simplicity of organisation. If it’s collaborative or it’s collective,

that’s almost as difficult as it being not on paper. Those are all challenges. In a way, they are not new problems though. We’ve got quite a few slides involved in this exhibition. And whereas once they were considered a standard form of presenting all sorts of information, they are no longer technologically so straightforward. They are considered archival, but how stable are they, and how easy are they to manipulate and reuse? Can you even get the equipment?

MO: We’ve done a bit of work on digitising.

TJ: Which makes them easier to manipulate and easier to exhibit today. But for how long? Another issue is different artists and their attitudes to archiving. Some are diligent recorders of their own practice, and some aren’t. And I don’t know whether that has a significance to the art history that will emerge later.

MO: If we only have the artwork to read, if there aren’t any research notes or contextual writing, it does mean less certainty around the concept, inspiration, and even materials that went into the making of the work. So sometimes artist archives can provide really valuable information for how you interpret a work and talk about it. I think you learn a lot from an artist’s notes on production, process and the thinking that informs the final artwork. The other nice thing you discover in artist archives is the interpersonal stuff. We’re trying to highlight that a little bit too – the friendships or influences, and we talked about collaborative making, but there’s also collectivity and community more generally.

TJ: Having conversations, or studying together.

MO: We’re trying to show those genealogies of artistic practice and the networks that go into making art. Because an artwork doesn’t just pop out one day – it comes from conversations and community.

TJ: I think that’s a paradox in archival organisation there! That does all happen, but when we organise the archives, we demolish that and say “this is the archive of artist X” and it’s contained in these boxes or files or whatever. In doing that we risk losing those connections with their tutors, friends, co-exhibitors, curators or anybody for that matter. Artist archives in New Zealand are not, in my opinion, terribly well served by the cataloguing and organisation that we have. It’s a small country and we should be working more collaboratively on making it easy to say, “here’s all the information that exists on artist X”, without expecting people to duck and dive across multiple catalogues, lists, indexes, finding aids. That’s something I would love to see improved.

MO: An aspect of the exhibition that we haven’t mentioned is the inclusion of publishing. It’s interesting to think about what has been published and therefore made more widely available, but sometimes even publishing something doesn’t mean it survives. There are books we’re really struggling to get hold of, books that are very rare and yet hold a critical role in telling art histories in Aotearoa.

A selection of archival slides by Pauline Rhodes, 1987–8

TJ: And after all, publications are routinely the output of archival research, and they represent the work that people like Jonathan, Julie and Karen have done with archival material. So yes, we’re pleased to present a broad selection of New Zealand art publications that seem significant to us and relate to those three art historians and to other material.

MO: Perhaps that pulls us back to where we started, and talking about audio. We also have some beautiful Ngāi Tahu waiata that will play in the exhibition space to reinforce the idea that archives, memory, whakapapa and storytelling exist in multiple forms.

TJ: Yes, we need to remember that stories can be told in all sorts of different ways – in objects, on bits of paper, on slides, on computer screens, and through music. They’re all valid and they all need problematising by scholars to work out where the connections are.

MO: And hopefully we’re providing useful material for future researchers to work with.

TJ: I think we are asking more questions in this exhibition than we are providing answers to, because these are all quite tricky issues. We wouldn’t presume to have those answers, but the exhibition should stimulate thought and debate on how some of the questions might be tackled.

Tim Jones and Melanie Oliver spoke in September 2025.