Commentary

B.

Bulletin

New Zealand's leading

gallery magazine

Latest Issue

B.21701 Sep 2024

Contributors

Commentary

What We Talk About With McCahon

Where to begin when writing or talking about Colin McCahon? I remember seeing one of his paintings for the first time, a North Otago landscape painted deep green with a sunless white sky on a piece of hardboard, hanging at the Forrester Gallery in Ōamaru while on a family trip when I was a young teenager. I felt like I recognised the landscape depicted from what I saw around me growing up, but I hadn’t seen it reduced to something so stark and primal before.

Commentary

Power and Possibility

Jonathan Jones, art critic for the Guardian newspaper, described it as “a spectacle that displays the power and mystery of our planet”. Made more than forty years ago, Walter De Maria’s 1977 sculpture The Lightning Field remains one of the world’s most ambitious manifestations of light-based art.

Commentary

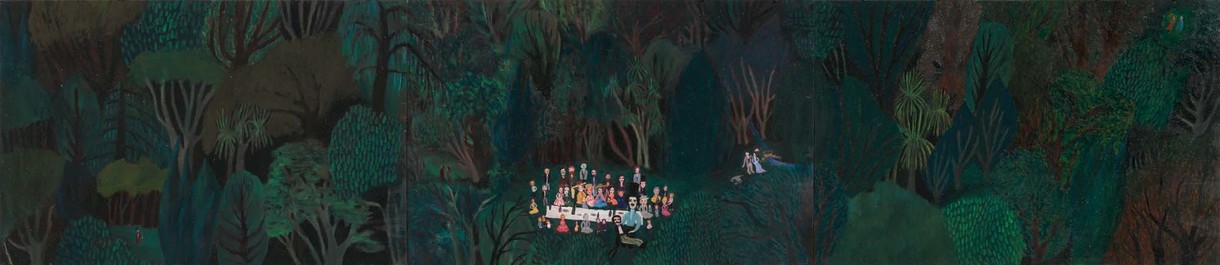

Doctor Jazz Stomp and the Webb Lane Sound

“Bill Hammond is long, lithe and tired, and was born several years ago. Is currently pursuing a Fine Arts course and trying hard to catch up. He is deeply interested in the aesthetic implications of sleep, sports the Rat-Chewed Look in coiffures for ’68, and dreams about blind mice in bikinis. He has never been known to sing outside the confines of his bedroom. Shows a marked but languid preference for the subtle textural nuances and dynamic shadings of washboard, cowbell, woodblocks, claves, cymbal, spoons, thimbles, tambourine, and the palms of the hands in percussive contact.”

Commentary

The Time Problem

Time is a problem in the contemporary world. There is simply not enough of it. Our to-do lists are too long; the time available to do what needs to be done is too short; the demands on our attention are increasingly brutal. Digital technologies track the minutiae of how we spend our days, but the sheer speed at which things seem to be happening makes it difficult to keep up.

Commentary

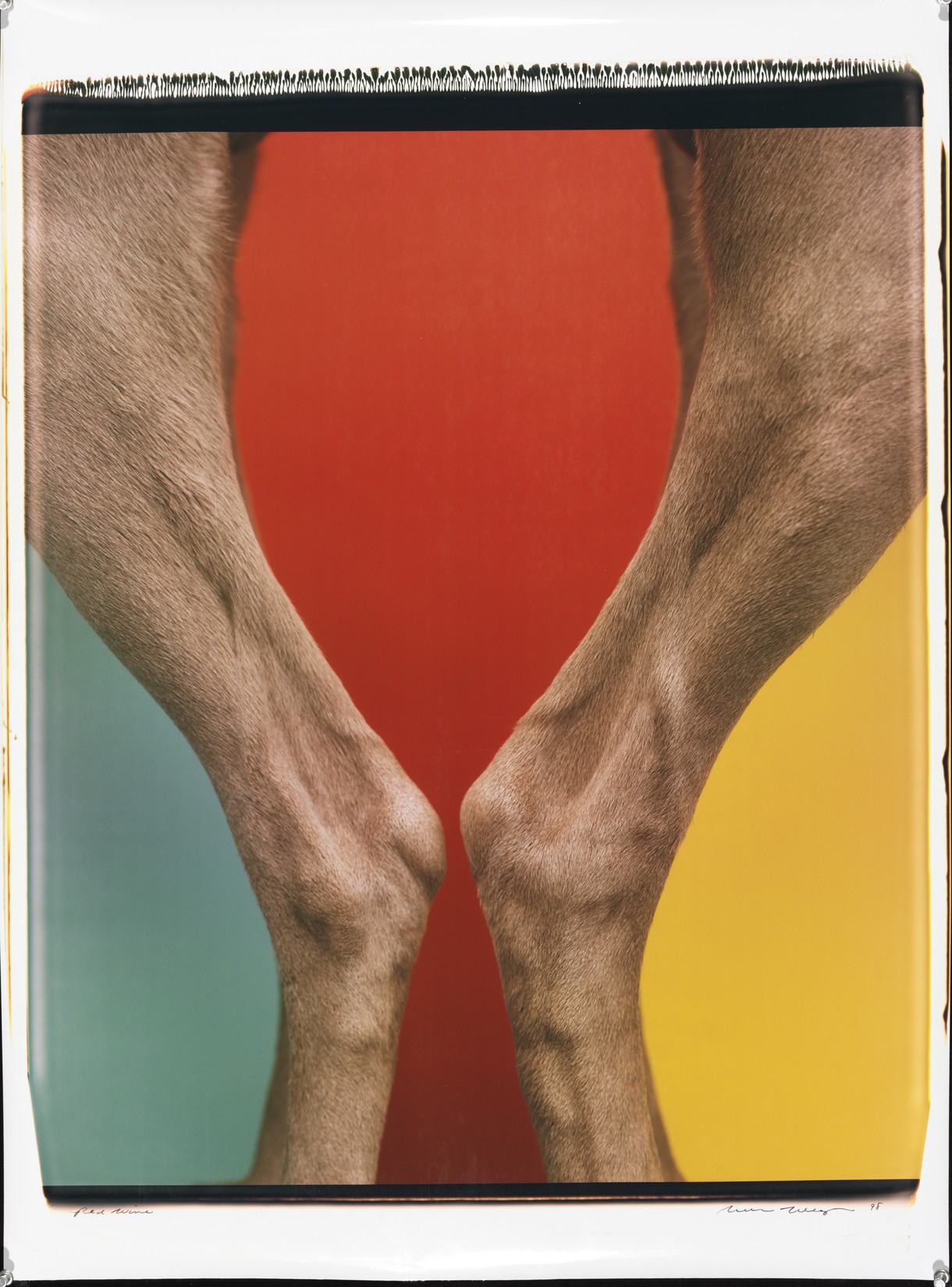

Anthropomorphism

Artist William Wegman has been photographing his Weimaraners in endless humanoid situations for more than four decades. Starting with Man Ray in the 1970s, Fay Ray in the 1980s and her subsequent offspring ever since, Wegman’s most popular artistic foil has been his pet dogs. For a number of reasons, this has occasionally meant his work has been thought of as naïve or sentimental – a trivial comic enterprise not too dissimilar to Anne Geddes’s notorious baby photos.

Commentary

Portraits for the Million

Scottish-born brothers John Tait (1836–1907) and Alexander Tait (1839–1913) established themselves as photographers in gold rush Hokitika in about 1866, the period in which Catton’s The Luminaries is set. While building up a broader picture of photographers for the Hidden Light: Early Canterbury and West Coast Photography book and exhibition, I recalled an interview with the novelist at around the time of her 2013 Man Booker Prize success, and her mention of having restricted her reading for a year before starting the novel to nothing published after 1866, giving the National Library’s Papers Past credit as a vital source. The trails and condensed stories of many of the photographers in Hidden Light were largely brought together via this same indispensable means.

Commentary

Do You See?

With the death of Julie King late in 2018, art and art history in Aotearoa New Zealand lost one of its great champions and major scholars. Julie was born in Yorkshire and grew up and was educated in Alnwick, Northumberland; she moved to Christchurch in 1975 to take up a role lecturing in the newly formed art history department at the University of Canterbury. She retired three decades later, having pioneered the teaching of New Zealand art in Canterbury.

Commentary

In Search of Rose Zeller

Enveloped in her dark brown coat and wearing an unconventional and distinctive striped shirt, Rose Zeller looks out from the canvas with an engaging and knowing smile. Painted around 1936 by her friend, fellow artist and teacher in craft and design, Daisy Osborn, it’s a rare view of an artist who, while scarcely remembered today, was an unconventional and respected figure during the interwar years.

Commentary

Everyone to Altitude

Late on a mild spring afternoon in mid-September, I travelled out of the city to a farm paddock somewhere up the line near Amberley, up front in a battered van carrying six drone pilots and their gear. The sun was low in the sky and Ōtautahi was framed in an arch of nor’west clouds. It was the first fine day in weeks.

Commentary

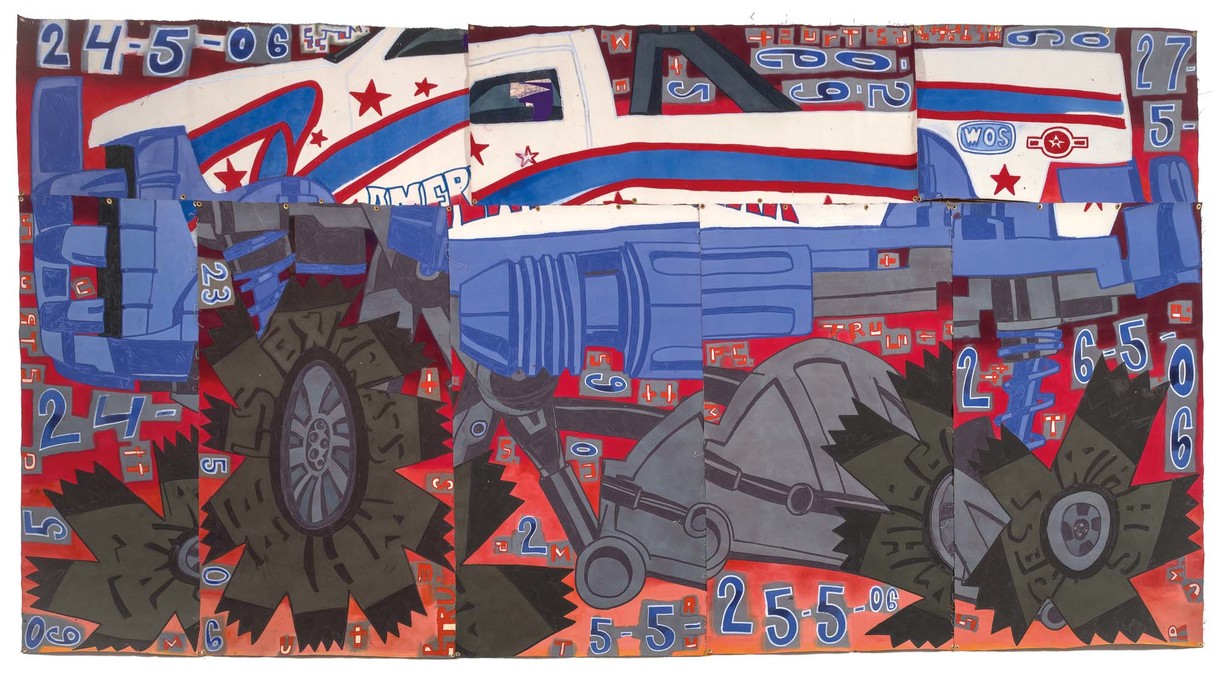

Philip Trusttum and the Squashed Painting

The painting is of a head on the end of a knife; it’s called Not Good (2014). Trusttum is better known for paintings that exude pleasure, their subject matter including physical exercise, sensuality and music, childhood, games and toys, animals, and ordinary domestic tasks such as mowing the lawn—life. There is pleasure and life too in the way he paints—in dancing, hyperactive line and luscious colour. It might seem anomalous, then, for Trusttum to paint something that is “not good”. When I interviewed him for Art New Zealand in 2011, he hinted at a bleaker side to his work, but said: “Stay away from explaining any darker meaning. I mean, we’ve got the earthquakes here.” There is something to be said, though, for complicating the perception of Trusttum’s pictures as purely hedonistic.