Philip Trusttum and the Squashed Painting

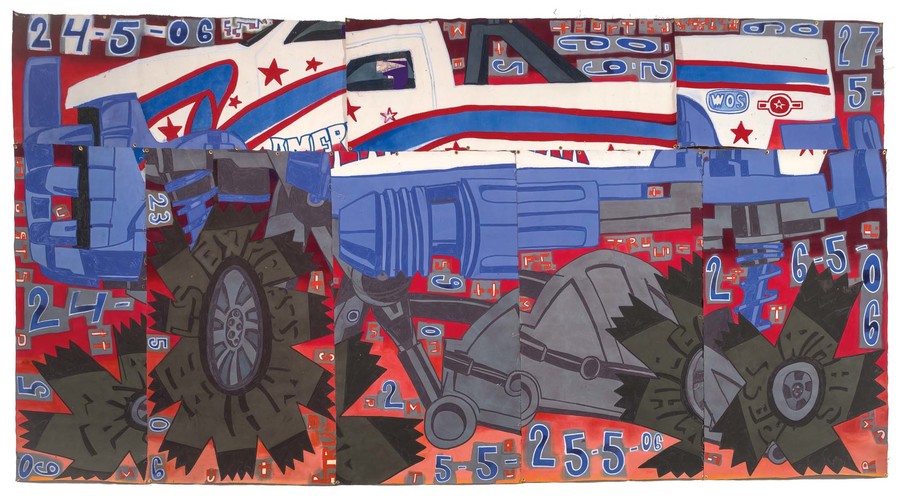

Philip Trusttum Amer 2006. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the artist 2009

The painting is of a head on the end of a knife; it’s called Not Good (2014). Trusttum is better known for paintings that exude pleasure, their subject matter including physical exercise, sensuality and music, childhood, games and toys, animals, and ordinary domestic tasks such as mowing the lawn—life. There is pleasure and life too in the way he paints—in dancing, hyperactive line and luscious colour. It might seem anomalous, then, for Trusttum to paint something that is “not good”. When I interviewed him for Art New Zealand in 2011, he hinted at a bleaker side to his work, but said: “Stay away from explaining any darker meaning. I mean, we’ve got the earthquakes here.”1 There is something to be said, though, for complicating the perception of Trusttum’s pictures as purely hedonistic.

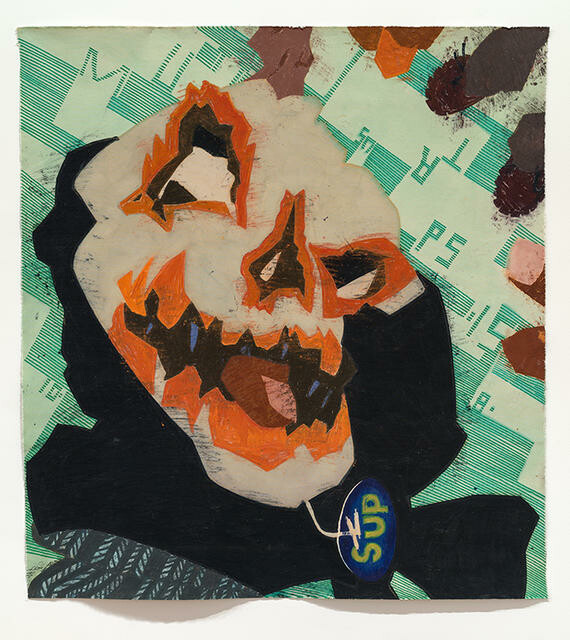

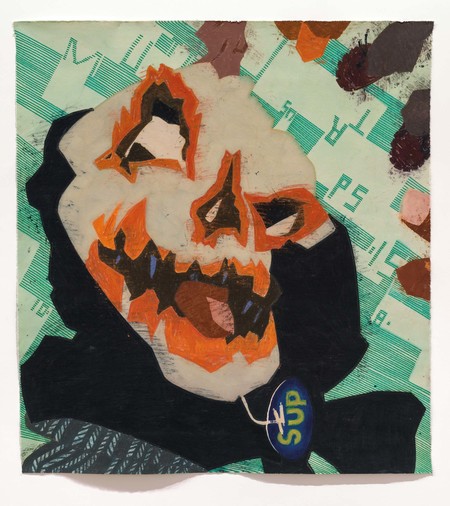

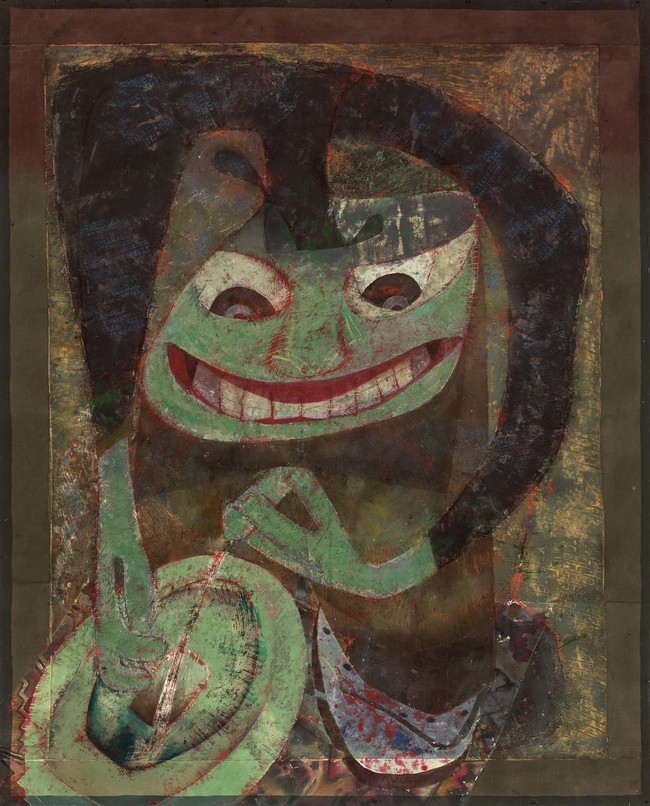

Philip Trusttum SUP 10 Aug 2015. Acrylic and marker on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the artist 2018

SUP (2015) comes from a series of works based on wearing his grandchildren’s Halloween masks and cleaning the house; innocence, comedy, hoovering and horror all mixed up together. Writing about the series, Warren Feeney came up with this wonderful sentence about the pent-up rancour that gets unleashed through seemingly innocuous, or merely tedious, household chores: “Tangled chords in claustrophobic interiors disrupt familiar ideas about home in aerial perspectives of rooms invaded by the ghoulish scowl of the culprit with the vacuum cleaner readied to do the damage.”2

Not Good is more explicitly ghoulish. There is little to distract from the head and the knife. Trusttum was painting in response to violent events around the world—conflicts in the Middle East, ISIS, and so forth. He sourced gruesome images, which, oddly, lose none of their gruesomeness in being translated from media photographs to bobble-eyed buffoons in weird cut-out shapes and gleefully bright colours. The knife may be a mere domestic trinket, one that Trusttum himself has owned for many years, but it says “terrorism” loudly enough. The head of the figure is an off-cut from another canvas, and at its crown the outline of an AK47 machine gun lends, so to speak, a disturbing edge. Weaponry earlier featured in Trusttum’s Alphabet series of the 1990s, albeit covertly, overpowered somewhat by the letter-forms.

Trusttum rarely tackles sociopolitical hotspots directly. Even his direct experience of the Christchurch earthquakes has tended to be channelled into drolly aesthetic reflections on their lingering aftermath. In Here We Go Again (2015) juddering patterns and hues register aftershocks, as much human and faintly irritating as geological or seismic—a simplification of the infernally complicated, ever-changing configurations of cones and signs navigated daily by the city’s long-suffering inhabitants. However, there is a certain violence in the aesthetic or formal construction of Trusttum’s pictures, such that whatever the subject matter—malevolent or beneficent—there is a tension that wrenches the pictures away from any bland or easy pleasures. Gifted colourist that he is (and his colour has been frequently extolled), it is Trusttum’s ability to bend, rend and, above all, squash that turns whatever he is painting into something thoroughly compelling.

The word “squash” does not usually have good connotations. It might mean to damage something, to reduce it from usefulness to uselessness, or to suppress or reduce its vitality. It is not a word that seems to go with painting at all: whoever heard of a “squashed painting”? How could even the effect of a painting be described as such?

The early twentieth-century modernist Wassily Kandinsky used the word “quetschtechnik” (“squashing”) to describe his technique of pressing a paint-laden brush firmly into the canvas so that it left small raised specks of paint around the edges of the mark. In this instance, squashing produces an inverse result, lifting the paint through the action of pushing it down. Lisa Florman has written that Kandinsky’s technique was designed to produce not only a sense of the materiality of the painting—the flat surface from which paint projects—but, when viewed from a distance, of immateriality or the illusion of space within or beyond that flatness.3 The latter, she argues, allowed Kandinsky to paint abstract works that nonetheless retained pictorial and spiritual qualities and evoked an imaginative world, rather than literal or decorative surfaces that might have seemed, in the early days of abstract art, to be dangerously close to not being “art” at all.

Trusttum’s paintings are not, or not purely, abstract. He is not anxious about the frankly material qualities of his paintings. If anything, he accentuates these qualities by, for example, cutting and layering canvas. Trusttum’s particular kind of squashing is about compressing the fullness and richness of life into his materials, into pigment and fabric. The painting is (roughly) flat: much has been written about—and much has been said to complicate—this simple fact that the much-maligned American critic Clement Greenberg had the temerity to point out. Life has a bit more body to it. So getting the fatness of life into the flatness of the canvas is likely to necessitate a degree of force. Historically, painters restrained themselves by using illusion—perspective and tonal gradation—thereby distracting the viewer from the materiality of the work. But Trusttum tackles the problem as vigorously as one of the protagonists of his 2011 rugby players series. He wrestles his subjects to the ground.

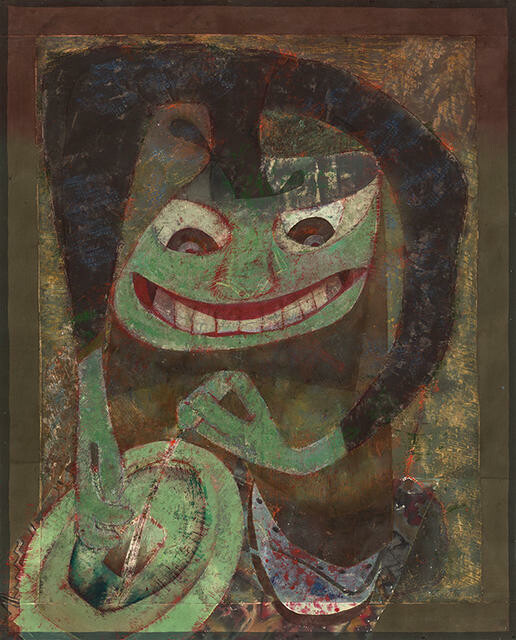

Philip Trusttum Peeing 1988–2001. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the artist 2009

Trusttum’s squashing technique is often so natural-seeming that it becomes invisible. After all, we are accustomed, as a result of the innovations of the early modernists and their successors, to seeing recognisable objects reduced to simple shapes. At times, though, Trusttum makes us more aware of his exertions, as in those works that have a top-down viewpoint. The crazed expression of the urinating figure in Peeing (1988–2001) merely exacerbates the unsettling effect of the splayed body and unreadable space—a space not aligned with our own upright orientation to the painting when hung on the wall. Text is a prominent feature of some Trusttum paintings, with the artist’s name and the date of the painting circling around the perimeter of the surface rather than confined to just the lower edge, again suggesting a view from above and around the surface. In the late nineteenth century, the aerial viewpoint was so unfamiliar that the French Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte’s Boulevard Seen from Above (1880) prompted one critic to describe it as “meaningless” unless the painting was shown on the floor.4 Trusttum’s pictures-without-horizons invoke the strange sensation of the artist standing over his subjects, stamping them down like someone trying to close an overstuffed suitcase.

In contrast to Kandinsky’s squashed/raised brushstroke, Trusttum’s method typically involves pressing the paint with newspaper to produce a blotchy, disembodied kind of surface. Moreover, his canvases tend to remain unstretched, more like textiles or mats, lightly crumpled, imprinted with paint. In an exceptional case, Martin’s Sewing Kit (1983), fabrics are both subject and material, the work taking the form of a kind of portfolio of canvases, which can be opened out or closed up, each canvas imitating samples or patterns from Trusttum’s son’s collection of sewing examples.

Earlier in his career, in paintings such as Red Berries and Still Life Garden (both 1973), Trusttum painted in oils on board, in what might be called an expressionist manner (closer in some respects to Kandinsky, but closer still to Vincent van Gogh). He had studied under the larger-than-life Rudolf Gopas, who seemed to encourage him to, effectively, go nuts; to lay it all bare. Expressionism in this sense has a rawness about it, as if whatever is inside you, or whatever you feel deeply about, has to be extracted and represented in such a way that it leaps off the surface, jumps out at the viewer and makes them feel something similar. Trusttum’s personality, though less erratic than Gopas’s, is effervescent—restless and voluble. But increasingly, from the late 1970s as he moved closer to his current styles and methods, rather than splashing and squirting, he started not to repress, but to compress— so the paintings are, on the surface, more placid but also denser, fuller and more concentrated.

Some of the largest of Trusttum’s paintings seem particularly crammed with action. Amer (2006) is one of a series of works based on the toy trucks of a grandchild, the vehicles flattened, fragmented and inflated so that small details fill vast swathes of canvas joined together to occupy, in the case of Amer, an area two-and-a-half metres high by almost five metres long (others in the series are even larger, such as the sixteen-and-a-half metre long 2007 painting Depot). Not only do we see the various surfaces and components of the truck, but scattered around, like debris from the artist’s act of flattening the truck, are the specific dates on which Trusttum worked on the painting. A long period of time is compressed into the conjoined surfaces.

To squash something need not be to ruin or kill it. Squeezing a piece of fruit, such as an orange or lemon, is the best way to get the juice out of it. With Trusttum, painting is a forceful but fruitful and life-affirming act.

Philip Trusttum Here We Go Again 2015. Oil on hardboard. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the artist 2018