What We Talk About With McCahon

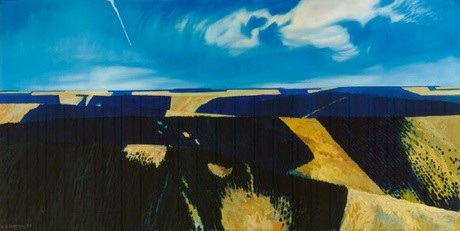

Colin McCahon Canterbury Plains (detail) 1951. Oil on canvas. Gifted by the family of Mary and Arthur Prior, 2017. Reproduced courtesy of Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Where to begin when writing or talking about Colin McCahon? I remember seeing one of his paintings for the first time, a North Otago landscape painted deep green with a sunless white sky on a piece of hardboard, hanging at the Forrester Gallery in Ōamaru while on a family trip when I was a young teenager. I felt like I recognised the landscape depicted from what I saw around me growing up, but I hadn’t seen it reduced to something so stark and primal before.

That initial effect has since worn away for me. I find McCahon weighty and in some ways unknowable now. I find it hard to untangle McCahon the person, his paintings, and the myth-making that wraps itself around him and his art. At the moment, I live in Waltham in Christchurch, the same neighbourhood that McCahon lived in from late 1948 to 1953. His house was on Barbour Street, a short walk across the railway tracks from mine, and he lived there with his wife Anne and their four children. It is still there, though it has been converted into a car parts supplier called Beachy’s Auto Spares.

One morning, while researching McCahon, I visited the house and tried knocking on the side door – the front door was covered with an overgrown vine and car tyres and bumper bars were piled in front of it. The doorstep had a pair of gumboots on it, and through the window I could see a white timber and cast iron fireplace with William Morris-esque flower tiles. No one answered the door. A coal train rumbled by as I left.

McCahon completed many paintings while living here; landscapes, often of the Canterbury Plains and Port Hills (which he had a clear view of from his front room), religious paintings, and some of his first abstract paintings. In August 1951, he went on his first overseas trip, to Melbourne, and was inspired by the art he saw (Cézanne, El Greco, Goya…) and by a chance encounter with the painter Mary Cockburn-Mercer, who gave him lessons in cubism.

Between July and September 1952, McCahon painted one of his best-known paintings, On building bridges: triptych, using the living room sofa as a makeshift easel for the hardboard panels. During this time, the Waltham Road overbridge was being constructed not far from the house. McCahon must have walked or cycled past the construction site many times, back and forward from his house to the central city. The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament was nearby too. Around the corner from his house and across Lancaster Park, the Cathedral’s bell towers and copper dome would have loomed over the skyline.

Ron O’Reilly, the city librarian from 1951 to 1968 and a supporter and close friend of McCahon, wrote in the introduction of the catalogue for McCahon’s 1972 survey exhibition that McCahon was not a Catholic, though “he has been attracted by Catholicism and gratified by the interest the Catholic Church has taken in his works”. In the same catalogue, McCahon wrote “my painting is almost entirely autobiographical – it tells you where I am at any given time, where I am living and the direction I am pointing in.”

This is the centenary year of McCahon’s birth, and he casts a long shadow in Aotearoa New Zealand. But how long? The idea of McCahon as being inescapable for artists is perhaps taken for granted. For this article I wanted to talk to artists who did not, on the surface, seem to be much influenced by McCahon, and I also wanted to talk to artists who make art in different mediums: textile and sculpture artist Emma Fitts, mixed-media and film artist and dancer Sriwhana Spong, and painter Tjalling de Vries. I asked them what they remember from seeing McCahon’s work for the first time; whether they have a favourite McCahon painting or series; whether they believe their own art is influenced by McCahon or they relate to it in some way; and what they think about his legacy or continuing influence. Here’s what they had to say:

Emma Fitts

Emma Fitts The Huntress with Silk and Felt on the Deck 2018. Courtesy of Melanie Roger Gallery

I don’t have a particular McCahon moment and I think part of that is because his paintings were so drilled into me at high school as a very popular folio board artist. There wasn’t a lot of room left for appreciation outside of this. It wasn’t until much later that I started to gain my own understanding of his work. This came from having the opportunity to see his work outside of the pages of a book in public galleries. His were some of the first really large- scale works I experienced. The idea that you could move past/along a painting as a process of comprehension was really memorable. I liked the way that the body was drawn into the experience of viewing his work, looking up and along; this was an experience totally other to the one I’d had of his work in books. I’ve always been interested by the way his work changed so much with getting out of the bush and experiencing an international scene. I find the journey of those paintings really inspiring.

I was intrigued by the Northland panels and the way that they brought a much wider influence in to the Titirangi studio. They were made all over his home – on the deck, in the living room, in the studio, everywhere – which I found really fascinating; the landscape can infiltrate the domestic in such a strong way, but it’s much less frequent to have the domestic infiltrate the landscape in a series of works.

I was interested in ideas of privacy and the domestic life of the McCahons while I was Parehuia Artist in Residence at the McCahon House. The house is really wonderful, and also really small. They had to be very clever with space to fit a family of six in there (baths becoming tables, exteriors becoming interiors) and it really does function as one body, one section moving into the next, a lot of it reconfigured by Colin himself and to his scale, I felt. The series of canvas works that I made for In the Rough were made for the interior spaces of the house; they were envisaged as partitions to offer moments of privacy from the kitchen to the living room, from the laundry to the bathroom or the bedroom to the forest.

Although I had gone to the residency with Anne McCahon at the forefront of my mind, the whole environment – their house, the museum, the huge kauri trees, the incessant rain, the studio hovering amongst it all – felt very intense and it was hard to escape McCahon’s paintings, which become so caught up in the landscape and conversations had. When it came to documenting my works, I tried hanging them in the house, but they felt more alive on the exterior of the home, where they intermingled with the textures of the landscape.

I began the residency with an interest in the life and work of Anne – I was curious about how she managed her life out there in the Titirangi bush and tried to keep her at the forefront of my mind. Everything always gets mixed up though, and I like that about life and people. Life is messy. McCahon and his legacy is messy.

Sriwhana Spong

Sriwhana Spong Ida-Ida 2019. Performance documentation, Spike Island. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett.Photo: Max McClure

My school-friend’s father had a collection of New Zealand artworks, and visiting her house was the first time I ever saw paintings that weren’t in books. I still remember the Hammonds in one room, the Fomisons in another, staring down at me from on high. In the foyer was a McCahon, one of his Teaching aids paintings (to my memory), and we would put our shoes underneath it when we came inside. I hadn’t been into a gallery before or seen modern art – not that I can recall anyway – so this was quite a formative experience for me at twelve. I remember being pretty ambivalent about the Hammonds, terrified by the Fomisons, and curious about the McCahon – roving numbers and just black and white. Who knew that could be art? What was this art thing?

Perhaps my favourite paintings would be his late works based on the book of Ecclesiastes. It seems to me that McCahon sublimated his struggles into his work – his battle with faith/God being the most present. And it seems so ridiculously poetic and apt that his last paintings were based on Ecclesiastes, which proclaims all human acts to be futile. For an artist to declare the futility of their own work at the very end, is to me a powerful gesture of submission to the cycle of life and death. I seem to remember reading somewhere that they were found face down? Perhaps I’m romanticising somewhat, but I do like them.

My work is not influenced by McCahon, although perhaps my very early black and white Super 8 films were unconsciously partly influenced by his black and white paintings. I relate to the works on a more personal level. I was raised in a rather dogmatic religious environment, which I was lucky enough to be able to walk away from. Leaving a system that I was indoctrinated into was a very difficult process of unbuilding and rebuilding; indoctrination is a very, very sticky thing to untangle. The Law, The Word, attaches itself to everything, and I see this in McCahon’s work. He’s the only artist I’ve encountered that somewhat captures this particular experience. I don’t know whether he ever resolved his questions, but his practice encapsulates to me a very deep struggle with faith and doubt, and the work contains a rawness and vulnerability because of this.

His shadow is only as long as New Zealand, and I do love that about his work. I remember reading somewhere that his exhibition A Question of Faith at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam was an attempt to bring him into an international modernist history that ultimately failed. If this is true, I think it says so much about the kind of artist he was. I think it’s an excellent thing not to be translatable into an ‘international’ canon – this failure is perhaps his greatest achievement as an artist.

Tjalling de Vries

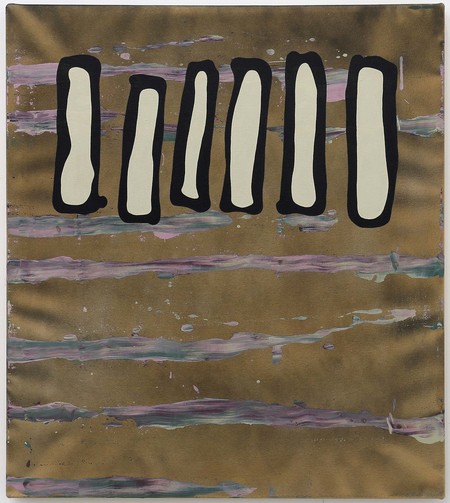

Tjalling de Vries Slab Crude 2019. Courtesy of Jonathan Smart Gallery. Photo: Vicki Piper

To be honest, I don’t know when I first encountered McCahon’s work. I remember reading about him when I studied art via correspondence school at Akaroa High. I’m sure I would have seen reproductions in art books – something that we all know does no justice to paintings, particularly not in black and white photocopies. I would also have seen his work at the Robert McDougall, but at that time the works that stuck in my mind were very different.

Coupled with this is that although I was brought up by two practicing artists, their artistic background was very much European, and that filtered into my own artistic interests. So I’m a latecomer really, but I have warmed towards his work over the years. There was no great knockout moment with McCahon and I... Taking all that into account, I don’t think his work has much influenced my own directly. I do think, however, that there are wider connections, in particular those relating to the process of making a painting.

Despite often being consumed by the landscapes around me and finding energy from being in, and a part of, the New Zealand landscape, generally I don’t use it in my work. Obviously McCahon does, and I see a strong reflection, particularly of the South Island, in his work. What strikes me most, in relation to my own practice, is that I am drawn to many of his works by the familiarity of the landscape and the emotional weight of the shapes, colours, and text. There is something in them that makes me think into and through the painting about the depicted world. At the same time, there are motifs that draw me back again to the fact that I am looking at an object, a painting made with a brush and a support. The works brilliantly ‘contain’ both these seemingly contrasting elements for me.

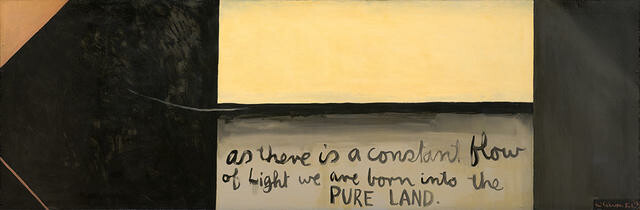

I don’t think I have a clear favourite work or series, although two from the Gallery’s collection are definitely up there for me. As there is a constant flow of light we are born into the pure land first pulls me into a seascape between two dark forms that feel like headlands, my eye is then drawn to the orange triangle and line to the left that flattens and distorts the painting. I am constantly moving between the two. It’s slightly uneasy, but that’s something I like a lot in paintings.

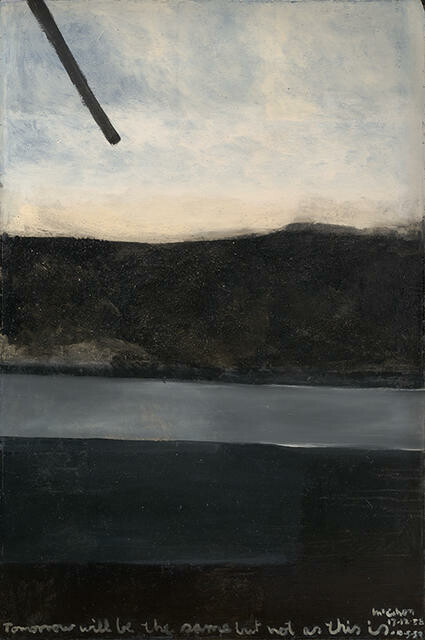

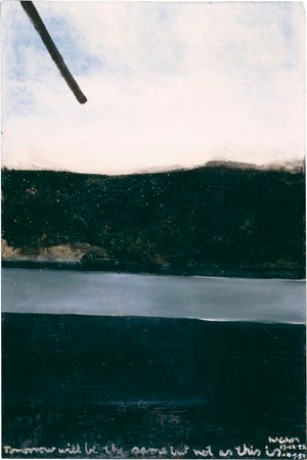

Something similar happens for me with Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is. It’s in the depth in the colours (despite using house paint!) and the basic landscape composition of horizontal sections against the text at the bottom and the linear motif hanging down from the top. I feel like text is a very difficult thing to use successfully in paintings, but McCahon made it function on multiple levels. I also enjoy the top-right chipped corner against the painting’s box frame. The kind of thing that is unlikely to be intentional, but does nice things for the reading of the edge of the work. And what a fantastic title.

I also found a work online that I liked the look of; it’s by no means a great work in his oeuvre but tickles my fancy nonetheless. It is a potato print called Hoeing Tobacco, a simple black print with clumsy yet attractive shapes depicting a figure doing just as the title suggests.

And as for the shadow he casts, I guess this depends on context, I have never particularly felt it myself but I am sure it was most strongly the case for artists that came directly after him and worked in a similar field. I suppose that if it means his work is still relevant and at the forefront of artists minds, then it is probably often true. I do think that his work reflects a New Zealand that was, and of which some elements remain.