The Time Problem

Rebecca Baumann Automated Colour Field (variation 4) 2014. 44 flip-clocks, laser cut paper, batteries. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2014

Time is a problem in the contemporary world. There is simply not enough of it. Our to-do lists are too long; the time available to do what needs to be done is too short; the demands on our attention are increasingly brutal. Digital technologies track the minutiae of how we spend our days, but the sheer speed at which things seem to be happening makes it difficult to keep up.

In-boxes fill before they can be emptied. Data streams past at a rate impossible to comprehend. Events that would once have consumed media and society for weeks or months at a time now last only one or two news cycles before they are displaced by the next big thing. It’s increasingly difficult to remember when something happened. The contemporary moment is characterised by both urgency and fatigue: these states are, of course, related.

Artists, as ever, were on to these shifts in culture early. Time has been both a subject and an overarching presence in contemporary art for a while now. Although art’s requirement for contemplation and reflection has always provided some form of resistance to the notion of ‘productive time’, recent art supplies a critique of the increasingly precise measurement of time demanded in the digital era – a corrective based on subjectivity and unruliness. Art can offer alternative chronologies in which significant moments are recorded or connected to others; or through which the passing of time might be apprehended. It disrupts any sense of the regularity or ubiquity of time. Above all, art offers a way to account for the experience of time, which has very little to do with numbers and lists.

It wasn’t always like it is now. I can remember, in the dim and distant pre-digital past, being extraordinarily busy – yet somehow there was more time in the day to do things, and they required less communication and fewer iterations to complete. In the early 1990s I was just out of university and in my first curatorial job, at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, and the youngest person on staff. Time worked differently back then. When I needed to communicate with an artist or a lender, I’d generally write a letter. (We didn’t get computers, or email, until the mid-1990s. And ‘toll calls’ – as they were then called – were expensive and needed to be placed through the receptionist.) The process for sending a letter was as follows. I would write what I wanted to say by hand, and give it to the gallery’s secretary to type on an electric typewriter. Because I was at the end of the pecking order, my letters went to the bottom of the pile and could take several days to come back to me for signing. If there was an error, I’d correct it by hand and send the draft back for retyping. The whole routine could take a week. And then I’d post the letter, and wait for a reply.

Marie Shannon Car Stories 2018. Single-channel video. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2018

When I recall this now, it seems unbelievably old-fashioned, ridiculously historical, as if I’d sent the letter with a carrier pigeon; as if I’m writing about 1932 rather than 1992. But perhaps those dates, sixty analogue years apart, have more in common than the almost thirty-year post-digital gap between the early 1990s and 2019. Digital technologies have not only changed our experience of space but altered our relationship with time. The world is more connected and history appears to be speeding up, at the same time that our attention spans have shrunk.

Against this volatile background, Now, Then, Next is an exhibition of contemporary works from the collection that offer different ways to think about time. All except one of the works was made this century: the most recent, Marie Shannon’s Car Stories (2018), was made only a few months ago. There are works by different generations of artists, reflecting a range of perspectives on the current moment. The problem of compressing time into space – of imbuing an object or an image with a latent sense of duration – is addressed by works that chronicle the multiple anxieties of the future or observe the persistence of the past in the present. Interestingly, an untitled installation by the youngest artist in the show, Sophie Bannan, reaches back beyond her lifetime into the cultural memory of the city, and into the experience of her grandfather, the late architect Maurice Mahoney, who with his business partner Sir Miles Warren designed many of the brutalist buildings the city lost in the earthquakes of 2010 and 2011. Bannan made her shelf of fragile ceramics from clay dug from the demolition sites her grandfather’s buildings once occupied: they stand as elegies to a vanished future. Objects are lost: memory endures.

There are several recent acquisitions in this show – and as I was putting the list together, I looked at them again with a particularly critical eye. When we’re acquiring contemporary works for the collection, there are many considerations, but a particular concern for me is how the work might contribute to a perspective on the present moment. We think about the quality of the work and its place within an artist’s practice, and about its physical longevity and its significance to our audiences; but beyond that I also find myself thinking about the way the work situates itself in time. What does it say about the way we live now? How does it build on (or usefully confound) the long history of works acquired for the collection? How might it be seen in the future? (This last one is the hardest to determine of course, and can only be guesswork: but it’s beholden on all of us to do what we can for the future from the vantage point of the present.)

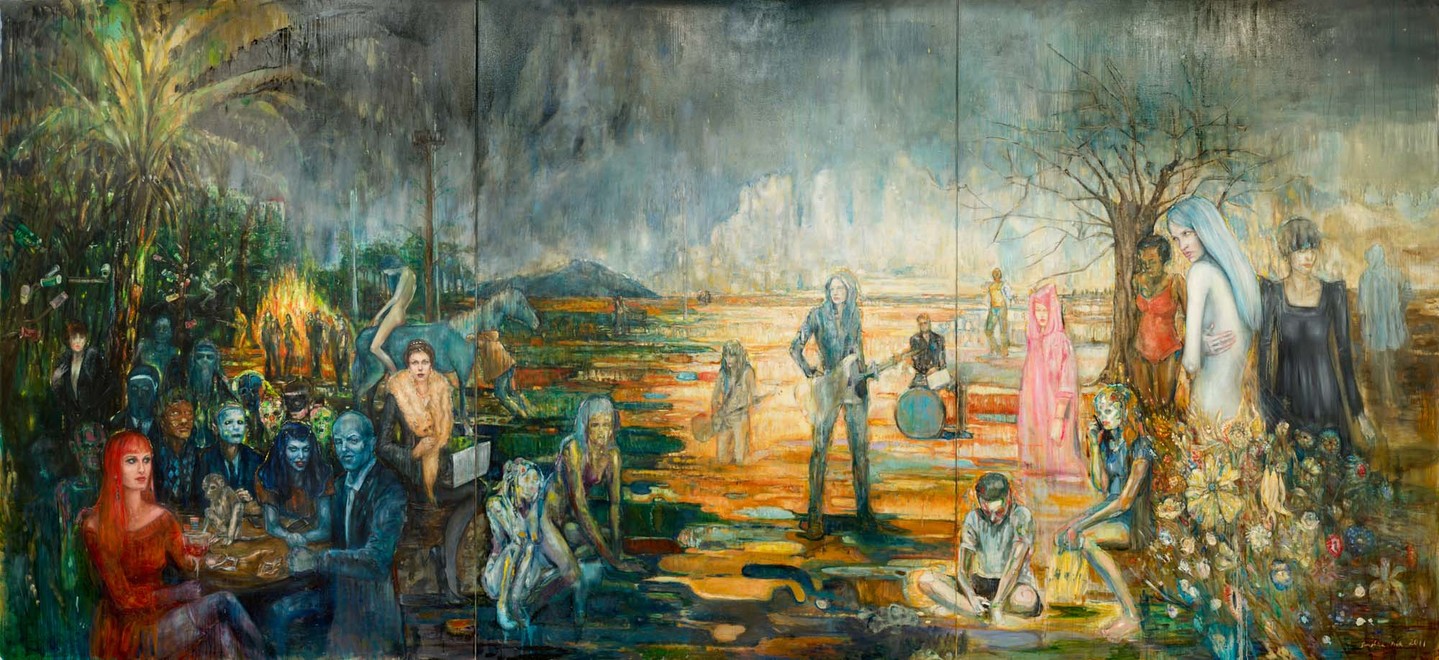

Séraphine Pick Everything Old is New Again 2011. Oil on linen. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the W.A. Sutton Trust, 2019

Séraphine Pick’s monumental Everything Old is New Again (2011) is an anchoring work in this exhibition. It was purchased earlier this year by the Sutton Trust, in memory of the modernist artist Bill Sutton, who retired as senior lecturer in painting at the University of Canterbury’s School of Fine Arts just before Pick arrived there as a student in the 1980s. It takes up a lot of space, and it brings together multiple time zones. For the past few years, Pick has been trawling the internet for figures in particular poses – “second-hand life models”, as curator Sian van Dyk has referred to them – reassembling them in new configurations on the canvas. In this work, people are texting on their phones and hunched over laptops while a vaguely 1960s-looking rock band fronted by a female guitarist plays on barren, blasted ground. Figures in a variety of historical attire rise like wraiths at the edges of the image. It looks like the end of the world, and it looks like a kind of 1960s utopianism gone bad, and it looks like right now.

While Pick’s work points to the cyclical nature of time, a different kind of cycle is intimated in Rebecca Baumann’s Automated Colour Field (variation 4) (2014). Baumann has assembled a grid of 44 flip clocks, replacing their number displays with coloured cards. Internal motors powered by batteries change the pairings of colours on the work almost continuously. Baumann says that when she was making these works she “was thinking about everything you feel in a day. Everything is always about that perfect moment, but really life is just a series of many moments.”

Neil Pardington Te Whare o Rangiora (Chair) 2002. LED/C-print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2018

Time can be measured as a series of fleeting moments, or in an idiosyncratic personal chronology spanning many decades. Car Stories is a road movie shot through the front windscreen, presenting a narrative of all the cars Marie Shannon has ever owned or regularly driven. She comments: “I’m using each car as a prompt to talk about times and events in my life, whether related to cars or not.” Or time can be manifest instead in what we leave behind, like Neil Pardington’s Te Whare o Rangiora (Chair) (2002), in which the kowhaiwhai-style patterning marked on the wooden arm of an institutional chair speaks of long hours of boredom and confinement by an anonymous patient. Pardington took the photograph in the disused psychiatric ward at Porirua Hospital, and notes that “it suggests a cry for help from within the asylum with no spiritual hope of any kind”. At the same time, it might also represent a person taking the time that they have available to remake an unsympathetic environment in a more congenial way.

While each of the recent works included in Now, Then, Next takes a different perspective on the nature of time passing, Tim J. Veling’s 2015 photographs of vegetation in the Christchurch red zone reveal the true no-man’s-land of the contemporary, in this instance pictured as an ex-urban no-place caught between history and the future. Veling has photographed the trees that used to stand in suburban gardens but now mark the vanished boundaries of properties, following the demolition of houses in the river suburbs following the Canterbury earthquakes. No one knows yet what’s going to happen with this land, and meanwhile, the trees continue to grow, the seasons change, and nature takes its course. In the distance are the volcanic Port Hills, continuing to form themselves in an implacable process whereby climacteric events like eruptions and earthquakes alternate with slow erosion over centuries. The present, in Veling’s photographs, is figured as uneasy ground in a state of flux and becoming – a place haunted by ghosts of the past, while its future is not yet determined. However we might think about time in our daily lives, the world we live in is operating on its own clock.

Tim J. Veling Halley Place, Avonside, 2015, Autumn 2015. Archival pigment print on gloss baryta paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2018