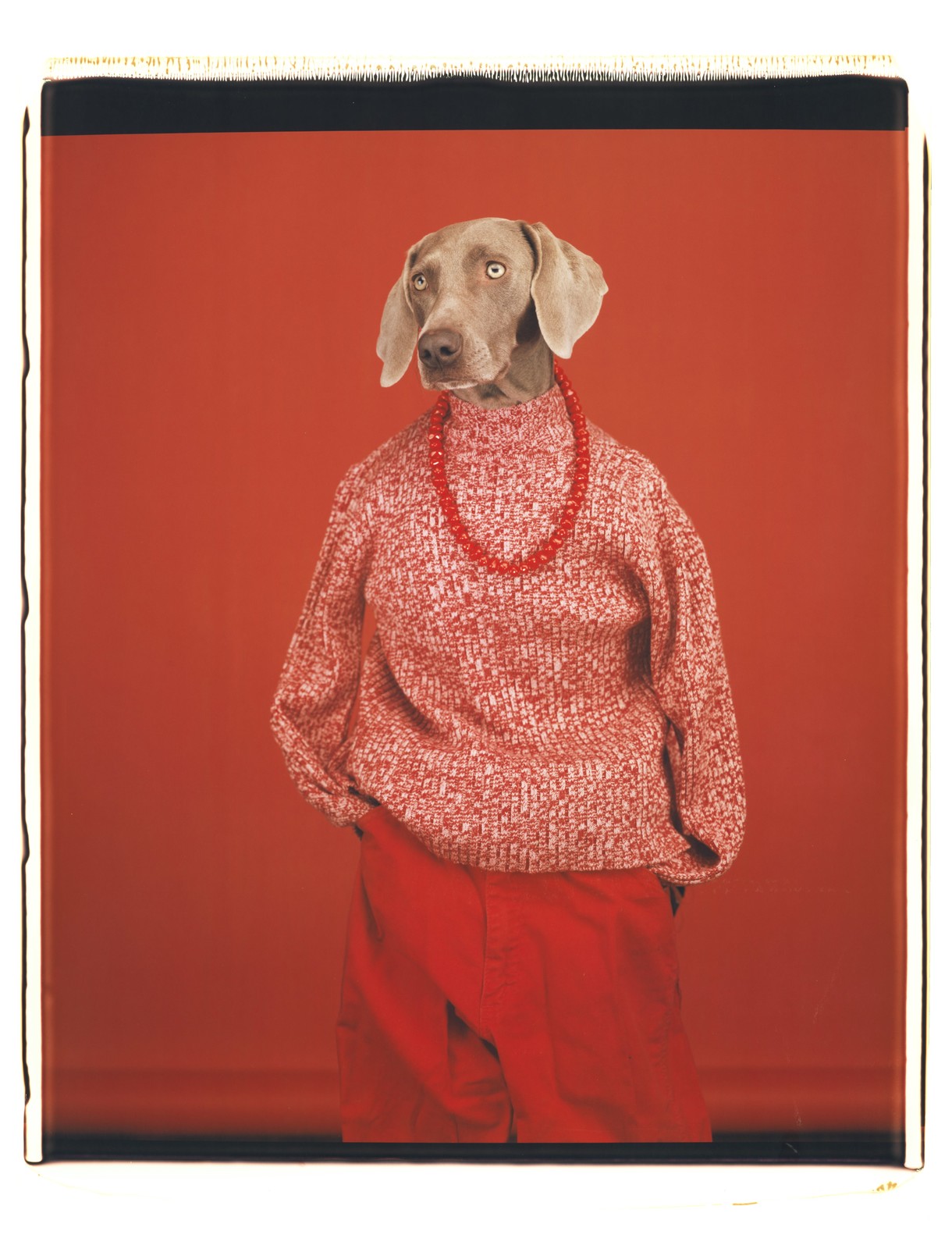

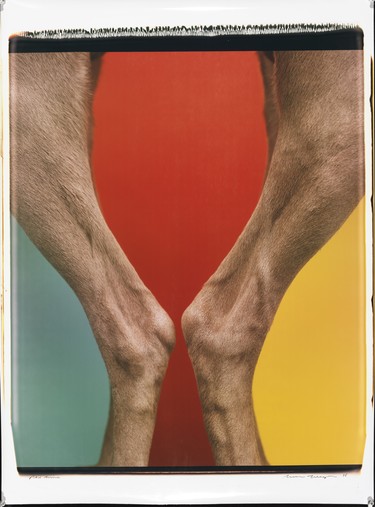

William Wegman Red Wine 1998. Colour Polaroid photograph. Courtesy the artist. © William Wegman

Anthropomorphism

Artist William Wegman has been photographing his Weimaraners in endless humanoid situations for more than four decades. Starting with Man Ray in the 1970s, Fay Ray in the 1980s and her subsequent offspring ever since, Wegman’s most popular artistic foil has been his pet dogs. For a number of reasons, this has occasionally meant his work has been thought of as naïve or sentimental – a trivial comic enterprise not too dissimilar to Anne Geddes’s notorious baby photos.

Primarily, this has to do with the common assumption that anthropomorphism, the attribution of human behaviour onto other non-humans, is a taboo not worth exploring. More importantly though, it is because he works with pets, a class of animal which has, only until quite recently, been openly denigrated as a narcissistic symbol that provides solace for the presumed disenfranchisement of modern life. Take for instance Ken Coupland’s damming criticism of Wegman’s photographs as “potboilers that strip his dogs of their animal integrity, encouraging a sentimentality whose true impetus is to make animals scapegoats for human weakness”.1 This bears all the hallmarks of a reading of Wegman’s practice that focuses solely on the way the dogs are manipulated and made to author a voice not of their own making. Such criticism is guided by the defensive idea that anthropomorphism devalues the human, that it trivialises the exceptionality of human life. It’s a stance that is, up to a point, extremely valid. After all, it’s a terrible idea to assume that the human is the sole arbitrator of what consciousness might be. Not to mention that we, humans, have a long history of using animals, and particularly their behaviours, as a possible validation for human social rules. Rosalind Coward’s hilarious essay “The Sex Life of Stick Insects” calls attention to this failing, noting in particular how nature documentaries so often revolve around the property-owning, patriarchal consciousness of human society. 2 But it’s not just this convenient mimicry of human society that anthropomorphism so easily produces. Think how often the comparison to animals, and animal behaviour, has been deployed to devalue and dehumanise other races.

As I said before, it’s not just this anthropomorphic bias that so troubles the reception of Wegman’s work. It is also that his anthropomorphic representations are of pets, an animal that for too long has been considered not just trivial, but regressive. Take for instance Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s infamous condemnation, that “Anyone who likes cats or dogs is a fool”, a declaration that turned pets into the deeply symbolic “Oedipal animals” who “draw us into narcissistic contemplation”. 3 Such sentiment is similarly seen in John Berger’s condemnation of the pet as the acculturated symbol of consumer society’s “universal but personal withdrawal into the private small family unit”. 4 However in the last few decades, perhaps in response to an exponential increase in pet-ownership practices, critics have begun to look at other means of accounting for the pet in contemporary human society. Key to such studies is their ability to look beyond the symbolic reading of the pet, to acknowledge and account for the actual practicalities of incorporating pets into human families. One way of doing this is to recognise that whilst the relationship isn’t necessarily equal it is still an asymmetrical accord that allows pets to adapt and alter the human household and social roles they are inducted into. For example, Adrian Franklin has studied the way houses are physically remoulded to account for specific animal behaviours and routines, 5 whereas Emma Power has looked at the way pets change and adapt the rosters and routines of the household, from feeding time to clearing the dishwasher. 6 In both instances the focus is not on the symbolic role of the pet, but on the way the distinct animality of the pet opens up the family to different experiences and vastly more collaborative ways of living. One way of accounting for such an expanded definition is to say that pets make humans more hybrid, that is, they expose us to a mixed experience of the world. This is something we see over and again in Wegman’s photographs, even with their anthropomorphic bent; there is a playfulness and resourcefulness to these situations which suggests a partnership that, whilst not exactly equal, is surely adaptive.

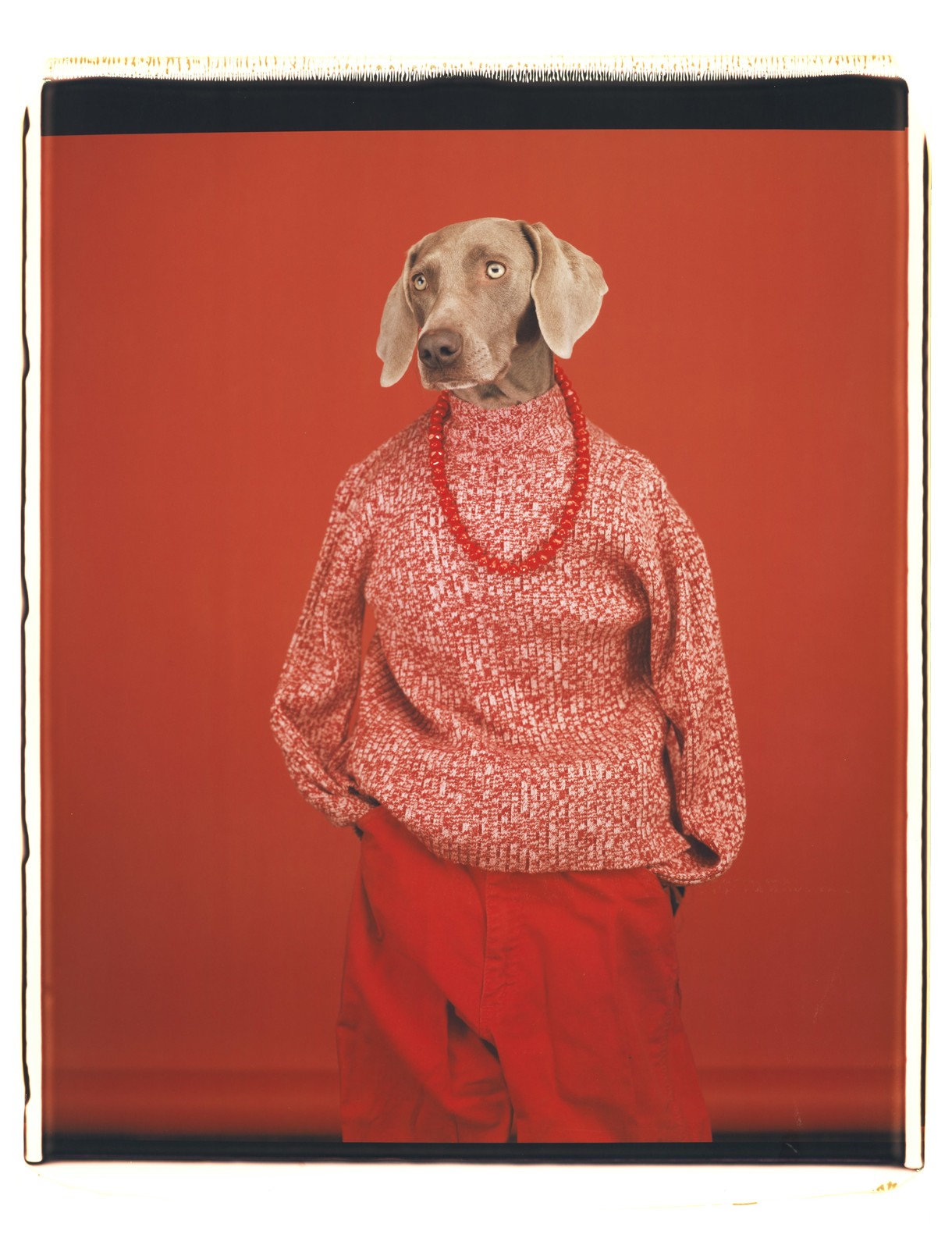

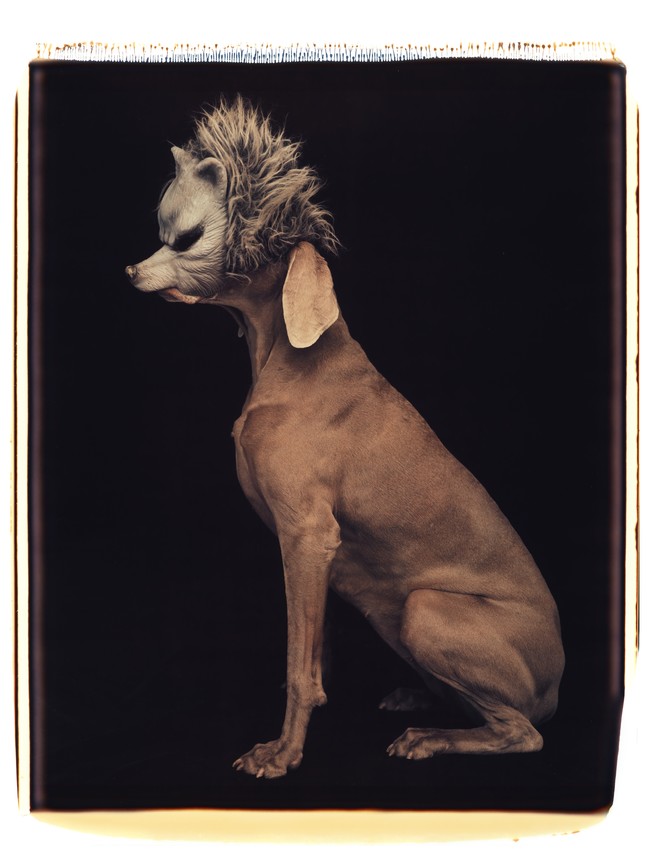

William Wegman Madame Butterfly 1997. Colour Polaroid photograph. Courtesy the artist. © William Wegman

Take Wegman’s earliest work with his first Weimaraner, Man Ray, in which he made videos and photographs of the dog balancing upon a ball, dressing up as a frog, partaking in spelling exercises, or posing in high heels. These works call into question the symbolic reading of the pet, exemplified by Berger’s condemnation of the pet as a device that aides the individual in their retreat from communal responsibility, particularly as it is guided by the faithful, unconditional love of “man’s-best-friend”. Indeed, in an early interview, Wegman specifically highlights the constraints of this “falsely sentimental” model of human-pet kinship, something exemplified for him by “dog food ads” and the Hollywood franchises of “Lassie or Trigger”. 7 Turning from this stereotype, Wegman chose neither to deliberately script, nor to rehearse any aspect of his photographs or short films, opting instead for an improvisational technique developed through the use of props to create and sustain scenarios that can be actively explored by both human and canine. Such collaboration is evident in the video work Dog and Ball (1973), in which Wegman follows Man Ray’s various poses as he attempts to engage with a large rubber ball. Keenly depicting the dog’s indifference to the apparent routine, as well as his ability to subvert such gestures by hunching over the ball and making it disappear from view, Dog and Ball is a good example of the way Wegman allows the animal’s point of view to disrupt the disciplinary parameters of stereotypical human-pet relations. This collaborative engagement is also evident in the video work New and Used Car Salesman (1973), in which Wegman, holding Man Ray upon his lap, monologues a brief speech about the trustworthiness and familiarity invoked by the appearance of a dog in advertisements, only to have Man Ray squirm about and unsettle such soothing symbolic representation. Picking up on these traits, Susan McHugh usefully suggests that Wegman’s practice is characterised more by “negotiation” than “subjugation”. 8

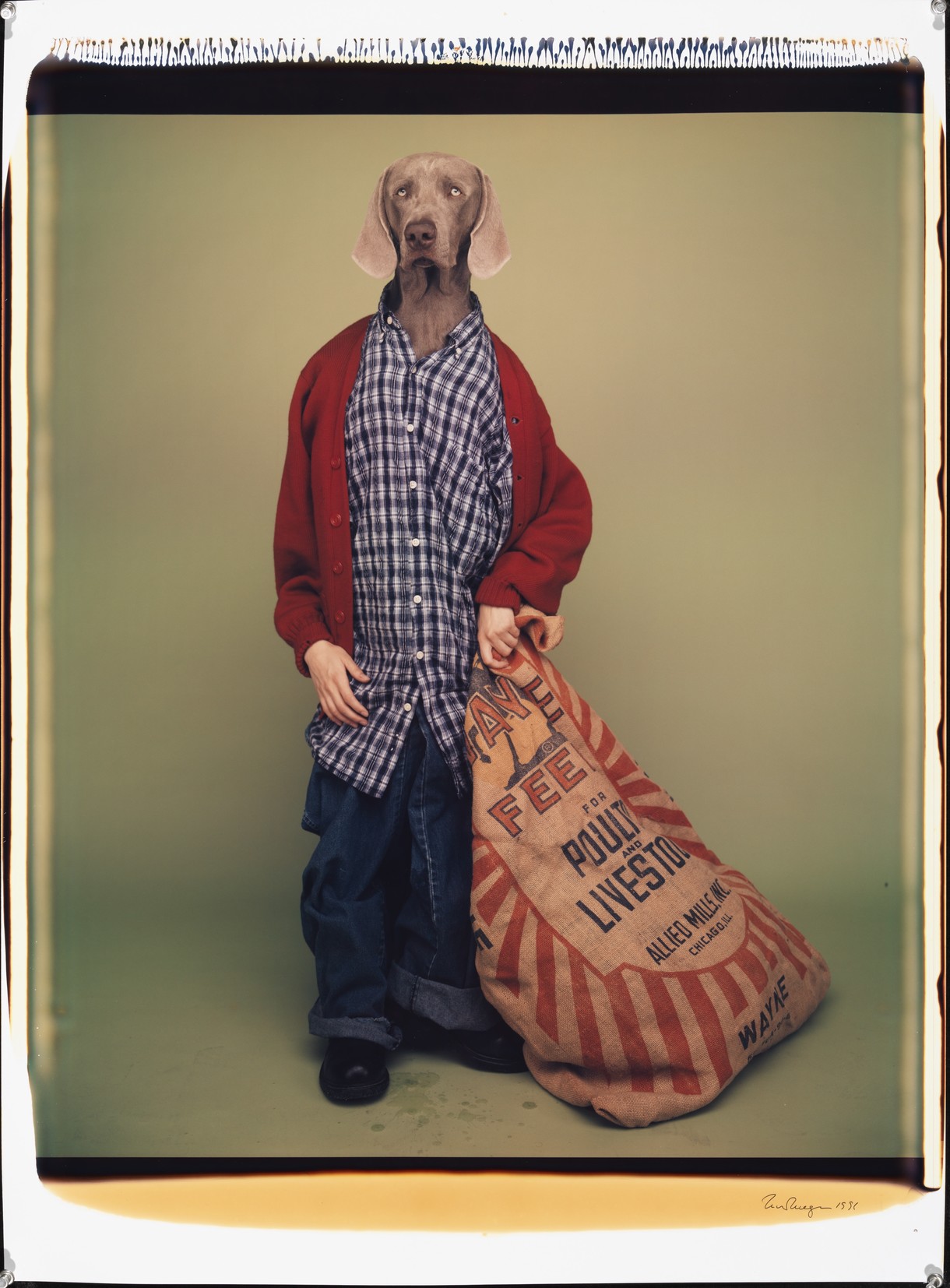

But this disruptive potential of Wegman’s work isn’t what significantly distinguishes it. Sure, he may be rehashing the velvet-painting stereotypes of cigar-smoking, poker-playing dogs, inverting their representation as a kind of rescued narrative, but there is also another element at play. This is perhaps more obvious as his practice develops from those original works where disruption and comedy were so apparent. Now what we get are increasingly moments of camouflage (of dogs becoming elephants or elegant women) or of a different kind of mimicry, in which the dogs echo classical sculpture or modernist cubes. What emerges is a more playful hybridity that points to an expanded register of possible human-canine collaboration. There is after all a kind of zoomorphic energy to this work, a fluid interchanging of animal registers we are familiar with from the overabundance of such frisson in the work of local painter Bill Hammond. Indeed it is this fluid interchange, this kind of dalliance with the human that is also so plentiful in Wegman’s work, granting it a similar sort of frisson – a moment of chance, or slippage in which we begin to glimpse something else.

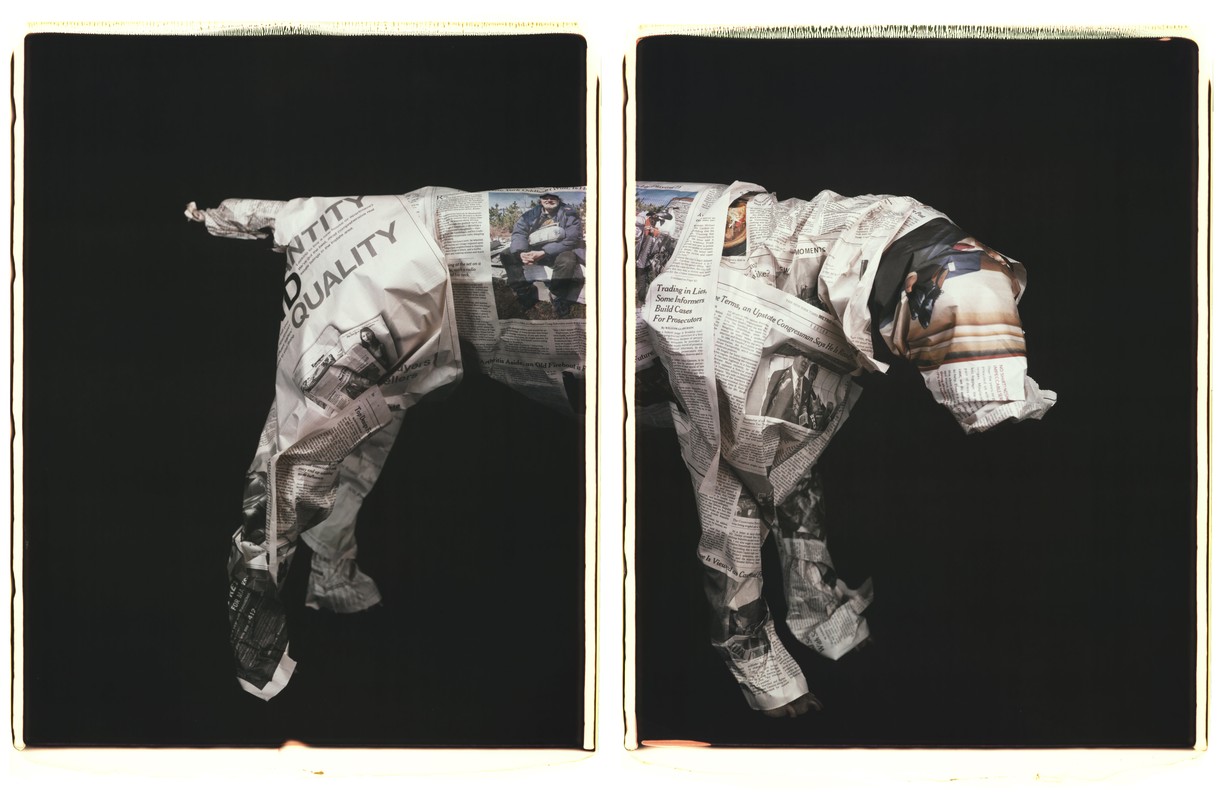

William Wegman Wolf 1994. Colour Polaroid photograph. Courtesy the artist. © William Wegman

William Wegman White Out 2014. Pigment print photograph. Courtesy the artist. © William Wegman

What I am hinting at here is easier explained in connection to the very slippage of how we define the human, in that as a category it is registered not by what it is but by how it behaves. When Carl Linnaeus tabled all the animals in his grand classification he left for homo sapiens the peculiar categorising attribute of an animal that is capable of knowing itself. 9 We can register this also in the words sapience and sapidity which define a very practical kind of taste, not only of being able to taste but of being able to enjoy and identify taste. 10 It is this kind of cognisance that has always defined the human, which is obvious when we consider our fascination with the apparent wolf- children (children reared with limited contact with human society) that recur throughout history. Indeed, only recently we proclaimed yet another group of humans, this time a family from Turkey who walked on all fours, as a kind of progenitor of and for the human.

The trouble is, of course, when we start to treat the human as sacrosanct, rather than expanded. This expanded connective notion of the human, whereby it is defined by a collaborative agency that connects it to the world, is a much better definition than a kind of reverse engineering in which we are constantly trying to defend the human. It’s this that makes Wegman’s practice so valuable. His work is less about how we depict dogs than about how we might expand the ways we think about our connection to non-humans. Which is why anthropomorphism is becoming so increasingly popular. Indeed it’s not surprising to go to biennials these days and see a wide array of non-humans doing all sorts of different activities. Whether it’s Francis Alÿs’s peacock strutting through Venice, Pierre Huyghe’s golden- legged dog interloping Kassel’s Documenta, or Hito Steyerl’s musings on the expanded possibilities for robots at Munster’s Sculpture Project, there is an ever-widening preoccupation amongst artists with what it might mean to live in the here and now of a contemporary culture that is willing to think beyond the scope of the purely human. In Wegman’s work we are similarly given the chance to glimpse this slippage of the human, so that we might see how the sapience that defines us may indeed be much more open, much more hybrid and much more collaborative than we have ever thought possible.

William Wegman Cursive Display 2013. Pigment print photograph. Courtesy the artist. © William Wegman