Studio Visit

Ron Mueck

I was in London last October and keen to visit Ron Mueck, but he wasn’t there: he’d gone down to Ventnor, on the Isle of Wight, where he has a studio. I spent my childhood in England, but I’d never been to the Isle of Wight. It’s in the English Channel; a Victorian retreat beloved by Tennyson, who wrote ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ here. It was also the home of the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, who made portraits of many of Tennyson’s guests. (When Tennyson took the American poet Longfellow to Cameron’s house for a portrait, he reportedly warned: “You’ll have to do whatever she tells you. I’ll come back soon and see what’s left of you.”)

I took the train down to Portsmouth, and then a ferry to Ryde, following an invitation from Ron. It takes about twenty minutes to make the sea crossing to the island, presumably it took longer in Tennyson’s day – he had enough time to write his elegiac meditation on sailing, ‘Crossing the Bar’, during one trip. (“May there be no moaning of the bar/ When I put out to sea …”) I’m not a great sailor, so I was delighted to disembark and take the sea air with the walk along Ryde Pier, an extraordinary piece of Victorian engineering, nearly 800 metres long, that carries you over the shallow waters to the small seaside town. At the other end, Charlie Clarke, who works with Ron on special projects, was waiting for me. It was another half hour in the car to Ventnor.

I’d last seen Ron and Charlie twelve months or so earlier, in Lyttelton for coffee: they’d been in Melbourne to work on Ron’s installation for the National Gallery of Victoria, and came over to talk to us about the work he was making for Christchurch. But I’d first met them during the exhibition of Mueck’s sculpture that toured to the Gallery from the NGV in 2010. The show opened not long after the first Christchurch earthquake and generated an audience of 135,000 people, with visitors in huge queues snaking around the block. There was something about the emotional vulnerability of Mueck’s figures that struck a nerve with Christchurch people, having come through a natural disaster; their introspection, their air of abstraction, the tension held in their bodies. The context for the work changed in Christchurch, as the sculptures became analogues for a set of recent experiences brought to them by local viewers. When it came to identifying the fifth ‘great work’ for the collection, in the series which marked the number of years the Gallery was closed for repair after the earthquakes, a sculpture by Ron Mueck seemed an obvious choice.

Mass, Mueck’s commission for the NGV, was monumental: a hundred human skulls in fibreglass and polymer paint, each five metres high, piled in giant heaps among historic paintings in the collection galleries. An ossuary. A bone-house at the heart of the museum. When I walked into it I felt overcome by its immensity, dwarfed by the scale not only of the works but of the human history that they represent: all those bodies, all those minds, once here and now gone, and us left, spectators among the wreckage.

That’s what Mueck’s work does: it quietly encourages you to contemplate your own humanity. His hyper-real figures are astonishingly life-like, but he very rarely sculpts them at human scale. Instead they are vast yet somehow vulnerable, like Wild Man or A Girl, or diminutive and intense, like Two Women or Youth. Their altered scale sets up a particular physical relationship – we loom over, we peer in, we circumnavigate their bodies. It is in the establishment of this relationship and its unfamiliar power differentials that a strange moment of emotional intimacy occurs with figures who are simultaneously human-looking but not-human. The sort of people you’d encounter in your everyday life, we’re less compelled to wonder who they are as to imagine what they may be feeling.

In Ventnor, we climb the stairs to Ron’s studio; a big open room on the first floor of an old building, pearly grey sea-light filtering through tall windows. The walls are lined with plywood. Shelves are stacked with boxes of materials. There are dozens of cans and bottles and jars and cups on tables and trollies. There’s a large pot of the plant known as mother-in-law’s tongue. There’s an elevated courtyard outside where Ron feeds crows. There’s a couple of massive white skulls, prototypes for Melbourne, and what turns out to be the first large-scale skull model, made – improbably – of cardboard.

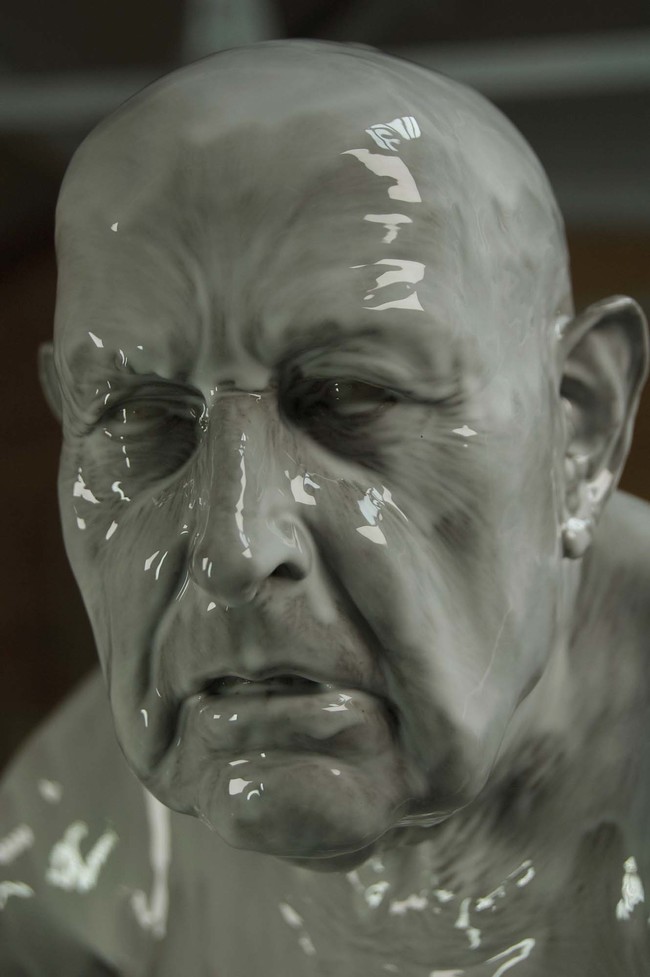

There’s a huge portrait head of a man with a very serious expression on his face, who looks so like a dear friend of mine from Christchurch that I’m taken aback. There’s Ron himself, shy, warm, welcoming. There’s a lot to take in.

The sculpture Ron’s making for the Gallery is one of the intense, compelling, smaller-than-life studies. It’s positioned on a table, in a lower level of the studio. It’s not yet finished. I’ve been sent a photo of it at an earlier stage, but nothing could have prepared me for the existential strangeness of the work when I finally see it: an old man, naked and irascible-looking, seated at a kitchen table, fists clenched, shoulders hunched, squaring off against a chicken who stands at the other end of the table with its chest thrust out like a tiny feathered general. The man and the chicken stare balefully at one another, locked in some eternal moment of precisely-balanced tension. I’m hard-pressed to say who the protagonist is: I’m immediately imagining a complex inner life for both the man and the chicken.

Is there a title? Not yet. “I usually title things late in the piece,” says Ron, “because you don’t know what you’re making until the end.”

I ask about the genesis of the work. Ron tells me he’d had an image of a solitary, contemplative figure at a table in his mind for some time. He started with sketches of the man at the table by himself, but they felt a bit sombre. He wondered what he might put on the table. “The idea of the chicken was as big a surprise to me as to the man at the table. But I knew immediately it was just the right blend of the mundane and the surreal.” He discovered he needed to use dove feathers to get the proportions right for the chicken, a little smaller than life size. After the sketches he made a smaller model, which caught the gist of the relationship between the two figures, their humour undercut by a feeling of profound uncertainty. Who is the model? An old family friend from the Isle of Wight, says Ron. A person who is frequently outraged by things. Things in the modern world. He recently told Ron a story about being outraged that there was nowhere to sit down at a gathering he attended. His figure-in-progress is bald right now, but there’s a full head of white hair coming. And underpants. The freckled skin on his back sags slightly. A mask of his face

ies by the figure’s feet. It’s slightly macabre. Some hair is attached to this one.

Ron works slowly. The works take a long time to make, and the ideas develop over time. He comments that he needs to find the idea for a work rather than invent it. It’s a long process.

“I’m very happy,” says Ron, looking straight at the figure, “with the skin. Its translucency.” From the closest inspection, it’s utterly convincing. I’m on my best behaviour, so I don’t reach out and touch the work, but if I were to, I imagine that its lack of warmth would be puzzling.

Ron and Charlie tell me about the table and chair: Ron is sculpting them in order to get the proportions right, which is a challenge, but he hopes that in the end no one will even notice them. The Formica table top, too, which Charlie is hoping to locate, needs to be exactly right: “It’s to do with the patina.” In the car on the way to the studio Charlie told me about the painstaking detail with which things are made, how Ron will spend a day making the specific tool he needs for the smallest job, if such a tool doesn’t already exist. He made something to apply the feathers one by one: they’re laid out in order of size on a piece of cardboard adjacent to the work.

It’s suddenly clear to me that the extraordinary physical realism of the sculptures is utterly at the service of their latent emotional content. They need to be completely convincing so that you don’t notice them at all. The details fall away, and what you experience instead is their psychological affect.

I catch the return ferry, but miss my train, and have to take a slow one back to London that stops at all the country stations. There’s a young couple in the seat adjacent who travel almost all the way with me; they’ve clearly been together for a while and don’t talk much. She stares out of the window and he looks off into the middle distance, his arms folded defensively. I’m in full Mueck mode after the hours in his studio, and I imagine them as potential sculptures in much the way you do when you’ve been looking at landscapes by a painter and then travel to the place where they were painted. But how would they see me? “Middle-aged woman scribbling in notebook, tired eyes.”

I’m thinking, too, about the untitled work back at the studio, the man and the chicken gradually becoming more and more vivid and real over the months to come as the final feathers are applied and the hair put in; and then about the work’s journey to London via Portsmouth, across the Solent from Ryde, before its final long flight across the world to Christchurch. The next time I see it, I think, it’ll be coming out of its crate at the Gallery. What will people in Ōtautahi make of it? What narratives will they bring to it? What personal histories? Face-to-face with the almost-humanity of Mueck’s work, we all find ourselves imagining the lineaments of his figures’ inner psychological worlds – and navigating the complexities of our own.