Inspiration and Consolation

Anthony d’Offay in Conversation with Justin Paton

Anthony d’Offay with Ron Mueck’s In bed 2005. Polyester resin, fibreglass, polyurethane, horse hair, cotton, second edition, ed. 1/1. Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, purchased, Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2008. © Ron Mueck courtesy Anthony d’Offay, London

In 2002, after two decades as one of the world’s most influential dealers of contemporary art, Anthony d’Offay closed the doors to his commercial gallery in Dering St., London. The years since, however, have been anything but quiet for him. In 2008, Tate and the National Galleries of Scotland acquired more than 700 works from d’Offay – a collection worth more than £125 million at the time, but acquired for the British public at its original cost price of around £27 million. Including works by Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Gilbert and George, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, Agnes Martin and Anselm Kiefer, the line-up is remarkable. Just as remarkable is the way the works are now being presented, in the form of more than fifty ‘Artist Rooms’ which travel not just to high-profile metropolitan institutions like Tate but also to small and often underfunded regional galleries – so that viewers might encounter Diane Arbus in Nottingham, or Ed Ruscha in Inverness. In addition to his work curating the Artist Rooms, d’Offay has continued to work closely with just one artist from his Dering St. stable – Ron Mueck. Senior curator Justin Paton spoke with d’Offay about Artist Rooms, his own formative gallery-going experiences, and his thoughts on Ron Mueck and his sculptures.

Justin Paton: What have you been up to? Which Artist Rooms have you installed most recently?

Anthony d'Offay: Well, we’ve installed a new Andy Warhol room at Tate Modern, which is extraordinary. There’s a big four-part camouflage painting, which is a masterpiece. There are six skulls, six self-portraits, a large dollar-sign painting, and a diptych from 1972 of dealer Alexander Iolas who worked with Andy all his life and commissioned the famous Last Supper paintings. And finally two large gun paintings, which are so important because, of course, they are of the same type of gun with which Andy was shot.

JP: Clearly it’s exciting for viewers to see these works for the first time, but this must also be the first time you’ve seen some of these works in many years, and certainly in these new groupings?

AD: Yes, many of the works I bought five, ten, fifteen years ago have been in storage, so one is seeing them, in many cases, afresh. It’s very exciting to see works of art which look stronger and stronger every time they come out.

JP: Why do the Rooms exist? What do you want them to do?

AD: Well it’s very simple. We want them to be seen by young people, who should begin to ask themselves questions about the meaning of the works, which stimulates them to ask questions of themselves. For instance, how is it that you and I are talking? I dare say that we had, when we were relatively young, experiences with art that made us ask questions of ourselves and perhaps got us to apprehend truth in some way – got us to find some strong ground to stand on for the first time. In my case, I began to see the world in terms of the experiences I had in my local museum as a young man, and that was something on which I was able to build. It was some sort of inspiration and consolation. Very often, I think, children experience intense unhappiness, as teenagers especially, and encounters with works of art can take that sort of experience into a different realm.

JP: So where did those moments of inspiration and consolation occur?

AD: I was brought up in Leicester, a medium-sized city in the English Midlands, and they had a really wonderful museum there with early twentieth-century German painting, painting by Francis Bacon, eighteenth-century pottery and porcelain, and stuffed animals and Egyptian mummies in the basement – a range of things to think about which were very important.

JP: And these things were transformative?

AD: They gave me some sort of basis on which to know myself, know who I was. I became very interested in looking at things, comparing things, and trying to work out why one was more powerful than another. As a child I was very interested in the Egyptian antiquities, and made models of them at home. And I was enormously impressed by the fact that there was a painting by Francis Bacon in the museum, and that it was by a living artist. That a living artist could be in a museum seemed an extraordinary thing.

JP: In public galleries today there’s often an anxiety that complex works of art will prove difficult for young audiences to digest – that they need to be explained or made entertaining. How does that tally with your own early experience?

AD: It was important that the museum was free, and one could go again and again. I never went on museum visits with schools, I just went on my own. My mother sort of parked me there when she went shopping. In some way I felt that I made friends with the works of art; that the works of art were very strengthening – I certainly felt that. And, you know, you can buy a postcard and take it home and feel that you possess it. It’s amazing how many people’s lives have been changed by looking at postcards after museum visits.

JP: You have spent your life since then working with art and artists. When you are going to see new works today, what do you hope for? What do you want from the experience of art?

AD: Well I think that all of us who are involved with contemporary art want that extraordinary breakthrough experience of falling in love with a young artist, or even falling in love with an older artist who one hasn’t totally appreciated properly before. Because that is such an intense experience. It’s a sort of revelation of knowledge.

Ron Mueck Dead Dad 1996–7. Silicone, polyurethane, styrene, synthetic hair, ed. 1/1. Stefan T. Edlis Collection, Chicago. © Ron Mueck courtesy Anthony d’Offay, London. Photo: Michael Tropea

JP: So tell me about your first experience of a Ron Mueck sculpture?

AD: It was very simple. It involved going to the exhibition Sensation at the Royal Academy in 1997, where Charles Saatchi had commissioned Ron to make some new sculpture, and standing awestruck by the sculpture Dead Dad. I asked Charles how to reach Ron, then made a date and went to see him, and made friends really. There’s a great innocence about Ron. He has no guile. He’s not worldly in the sense that Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst are. He’s a very retiring person. His world is really his life at home and what happens in the studio – those two things.

JP: And that sense of concentration and intensity is present in the sculptures.

AD: Absolutely, yes. He’s an extraordinary artist. It always feels like an honour to be involved in helping him to make exhibitions round the world and encouraging him, I hope, to make new work.

JP: He is the one artist you have continued to work very closely with since closing your gallery in 2001. Why is that?

AD: I would like to think it’s because we’re very good friends and trust each other. And maybe that trust was more important to him than having high-profile dealer shows. In fact, pretty much most of the time there’s a museum exhibition of his somewhere in the world, and I’ve been involved in helping to make those things happen. The work, when it’s sold, usually goes to museums, and I think Ron appreciates that.

JP: Across the thirteen or so years since the breakthrough sculpture Dead Dad – a surprisingly short time when you reflect on it – how would you say his work and his concerns have evolved?

AD: I think that he always takes risks, always makes something new, something he’s never made before. Just think for example about the recent sculptures. Drift is completely unlike anything else he’s ever made, and the same is true of Youth and Still life and Woman with sticks.

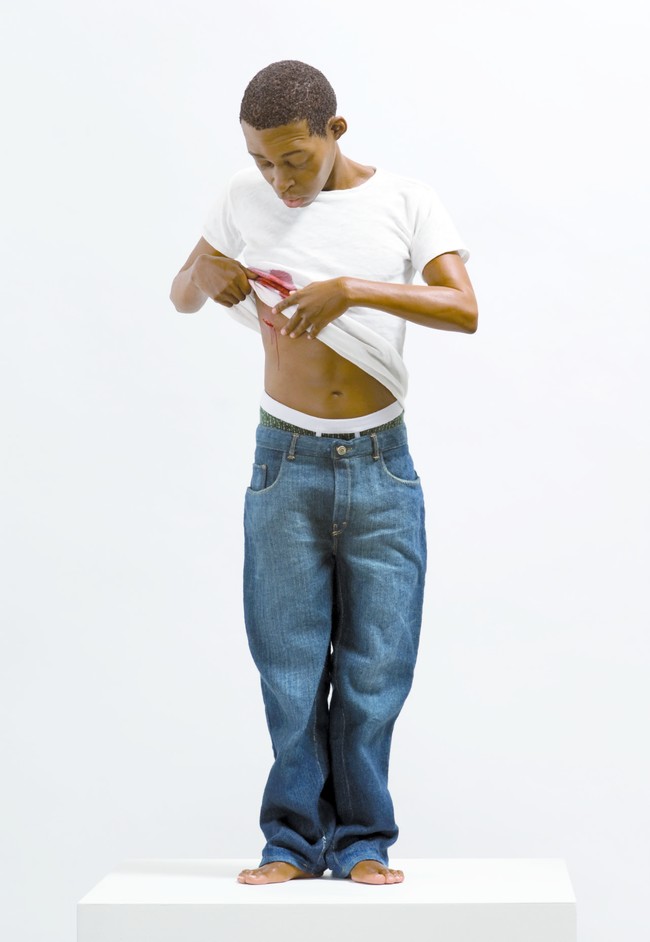

Ron Mueck Youth 2009 Silicone, polyurethane, steel, synthetic hair, fabric, ed. 1/1, Anthony d’Offay © Ron Mueck courtesy Anthony d’Offay, London. Photo: John Spiller

JP: I was very struck, visiting Ron’s London studio, by how incredibly small and modest the setting is. I’m not sure what I was expecting – somewhere larger and more clinical.

AD: I always think that it must relate in some way to the place where he made toys and puppets when he was a child in Melbourne.

JP: And not only how small the space is, but how intensely hands-on and observational and even intuitive Ron’s making process is. Do you think this makes him unusual among contemporary artists, where work is often outsourced or put in the hands of other makers?

AD: I think that he stands alone as an artist, in the same way as you could say the painter Lucian Freud stands alone as an artist. And interestingly enough, both of them have come from German origins, were brought up speaking German and have some kind of relationship, however vague, with the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity artists of the 1920s, and perhaps even with German romanticism.

JP: And a ‘northern’ pallor and sombreness…

AD: Yes, a Northern Renaissance feeling to the work. There’s a show of Lucian Freud at the Pompidou at the moment which makes him feel extremely German in a very French atmosphere.

JP: Ron’s exhibition in Melbourne received an extraordinary number of visitors by any standards – and his shows do this wherever they open. Why do you think this occurs? What accounts for the extraordinary reach of the work?

AD: If you take the trouble to speak to people in Ron’s exhibitions, and ask them how they came to see the show – Was it because they read a review? Was it because they saw advertising? What was it? – they all say pretty much the same thing, which is that a friend told them that under no circumstances must they miss this extraordinary experience. You know as well as I do that if a friend says you’ve absolutely got to read this book, or you absolutely must not miss this film, then one takes that seriously. I think also that Ron bypasses that rulebook for understanding the development of twentieth-century art – that is to say, the idea that you have to know about abstraction and cubism and surrealism and all those categories. I think, with Ron’s work, you can respond to it in an immediate way because it speaks to you at a deep level. People feel moved immediately by the sculpture, because it draws out strong emotions, very often to do with fear, loneliness, melancholy, daydreaming – things which people experience all the time but don’t always speak about. I can’t think of another artist who investigates those territories so thoroughly.

JP: When Ron emerged as part of the controversial Sensation exhibition he was discussed alongside the other so-called Young British Artists of that moment, Damien Hirst chief among them. A decade and more later, do you think he still sits with that group, or do other connections now seem more relevant?

AD: I don’t think he really sits with that group at all. I think he’s an artist apart. He comes from his own place. As we’ve said, he seems to belong to, if anything, that Northern European world of feeling. There are two ways of thinking about European art. One is the warm Mediterranean – voluptuous nudes, a guitar and a bottle of wine. And the other is, if you like, German painting, which is much colder and harder and hits in a much more sensitive place.

JP: When you returned to London from Ron’s exhibition in Melbourne, you were planning to visit Sacred Made Real, the National Gallery’s exhibition of hyper-realistic seventeenth-century Spanish religious sculpture. Did you see the exhibition?

AD: I certainly did. And it was impossible not to see some parallels with Ron’s sculptures. If you consider that Ron’s sculpture is all secular, and that the Baroque show was all to do with the spiritual world, it made a very interesting contrast.

Ron Mueck Still life 2009. Silicone, polyurethane, aluminium, feathers, stainless steel, nylon rope, ed. 1/1. Anthony d’Offay. © Ron Mueck courtesy Anthony d’Offay, London. Photo: John Spiller

JP: There are overt references to historical Christian art in several of Ron’s new sculptures – to crucifixions in Drift, to the wounding of Christ in Youth, and to imagery of sacrifice in Still life. What do you think Ron is saying in these works about the relationship between contemporary art and matters of faith and belief ?

AD: I think one of the things art must do is address the human condition. And mortality is something one comes back to again and again – the meaning of life, and the brevity of life, and the suffering that people have to endure. I think that the only difference about being older is that people grow more used to suffering; not that suffering lessens or ceases. And Ron seems more conscious of that in his recent works. That suffering is part of the power of the works.

JP: And strangely, human suffering seems especially present in the one work where Ron portrays a nonhuman subject – Still life.

AD: What a daring work to make. What an extraordinary idea, and to be able to bring it off. The work is truly shocking, isn’t it?

JP: It is. And while being a simple still-life subject, it seems also to be about all manner of larger things – amongst them violence and even war.

AD: It seems to relate to us in a very real way. And it also has extraordinary sexual overtones or undertones. It’s one of those works of art, and I think it’s characteristic of Ron when one says this, that once you’ve seen it it’s with you for the rest of your life. You’ll never forget it. Ron is so clear, so focused, so right. You can imagine that sculpture going wrong half a hundred times. But he’s incredibly sure-footed.

JP: This is a rather cruel question to end with, but if you were forced to do without all but one of Ron’s works, which would you stay with, and why?

AD: I know which work I’d stay with, and that is Mask II, the sleeping self-portrait, which is a work we are always lending to museums – twelve months a year. And that is because, according to my own understanding, it is the artist making his work. He’s dreaming his dreams. He’s dreaming the sculpture. He’s going to wake up and say, ‘I’ve got a good idea’. And there’s something very beautiful about the way you look at it from the front and it takes your breath way because it’s so lifelike, even though it’s colossal, and then you walk around the back and you see how it’s made – that it’s just a made thing. Come round the front again and it’s almost breathing. It’s a miraculous thing.

Ron Mueck Mask II 2002. Polyester resin, fibreglass, steel, plywood, synthetic hair, second edition, artist’s proof. Private collection. © Ron Mueck courtesy Anthony d’Offay, London