Confonting Portraiture

Ron Mueck Mask II 2002. Polyester resin, fibreglass, steel, plywood, synthetic hair, second edition, artist's proof. Private collection. © Ron Mueck courtesy Anthony d'Offay, London

When it comes to creative encounters, there can be few that match the first sighting of a Ron Mueck sculpture. As with other landmark events, I suggest you are unlikely to forget exactly where you were when that formative experience took place.

For me it was the 1998/9 exhibition New Neurotic Realism, at the Saatchi Gallery in Boundary Road, London. An Antipodean, I had the feeling of being thrown in at the deep end, amongst so much new and unfamiliar work by equally unfamiliar artists. The viewer became voyeur when confronting Martin Maloney's large and deliberately badly painted images of urban subcultures at play, and was then forced to walk the plank for immersion in Richard Wilson's vertiginous oilfilled installation. Every work in this exhibition conspired to stop visitors in their tracks, and none more so than Ron Mueck's. One of the first challenges was dealing with his wilful manipulation of scale, after which it was a matter of approaching with caution to examine in closer detail his astonishingly lifelike creations. Once over the shock of the new, first-time viewers could then stand back and observe other visitors coping with similar sensations.

Mueck began crafting his signature sculptures in 1996. His style emerged as if fully formed, and within two years had given rise to such celebrated figures as Pinocchio, Dead Dad, Angel and Mask (Self Portrait). He has an aversion to working at life-size, but whether they are dramatically larger or disturbingly smaller than nature, all his sculptures achieve a larger-than-life quality. The previous standard for three-dimensional realism in New Zealand was set in 1988 with the touring exhibition of American Duane Hanson’s Real People. But while the work of both sculptors depends on an intensely lifelike detail, Mueck’s subjects occupy an entirely different realm.

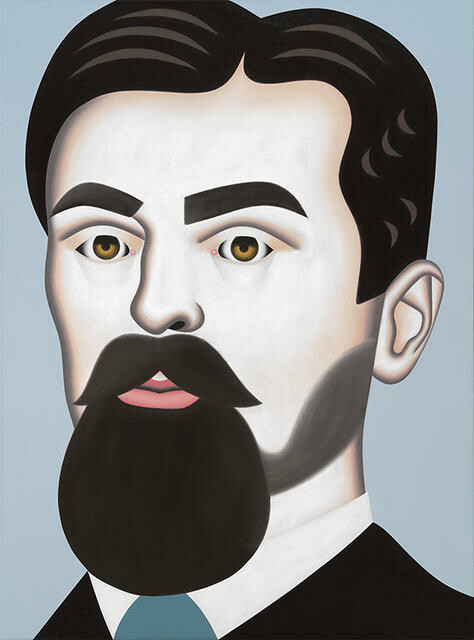

Through his deliberately unsettling changes to size and scale, Mueck deflects any direct comparison with ‘real life’, and so draws attention to his main point. And while Hanson’s ‘real people’ are a celebration of the mundane, in a sense Mueck’s are even more so. Many are presented in natural states – newly born or asleep or dead – and with minimal props or clothing. They are obviously based on particular individuals, but with the exception of Dead Dad and Mask II (which depict the artist’s own father and the artist himself respectively) they are not identified. As representations they go far beyond – and beneath – their immaculate finishes in their immortalisation of various stages of life. Human characteristics are laid bare and presented for scrutiny. In Mask II, for example, the artist is oblivious to our intrusions, while his monolithic scale suggests a timeless quality, and is perhaps a reminder that deep sleep can be likened to a near-death experience.

Among the issues raised by Mueck’s unique vision is the very nature of portraiture itself, one which might be approached from the point of view of the more familiar painted image. Although a vital part of the art history of this country, the portrait has long been overshadowed by a popular preference for the landscape. The latter has been the default setting, stimulated by the sheer quantity of suitable and accessible subjects, and further assisted by a generally agreeable climate. Not surprisingly perhaps, New Zealand’s search for distinctive local themes has been somewhat self-effacing, focusing on interpretations of the landscape rather than the people who inhabit it.

Following the invention of photography, the death of painting was announced – somewhat prematurely – in 1839. The tradition survived and was transplanted in New Zealand, and by the second decade of the twentieth century Christchurch had taken over from Dunedin as the country’s leading centre for the visual arts. This pre-eminence also became evident in local portrait work by such artists as Elizabeth Kelly, Archibald Nicoll, Sydney Thompson and Elizabeth Wallwork. Later, this city produced what would become the country’s most popular of all such images, Rita Angus’s 1942 Portrait of Betty Curnow, famously described by Peter Tomory as ‘a portrait of a generation’ and by Frederick Page as ‘more than a portrait … a revelation of the subject’.

But the landscape continued to dominate the easels of New Zealand, and the painted portrait faced further competition in the late 1940s with the arrival of abstraction. In 1968 Gordon H. Brown observed that the previous half-century had seen the practice fall into ‘general disrepute’, largely because artists were disinterested and had allowed it to be taken over by photographers. But if it had reached a low point in the late 1960s, portraiture was about to be revitalised. The focus now moved north to Auckland where the challenge was taken up by a new generation, among them Ian Scott, Michael Smither and Robin White, who had trained at the Elam School of Fine Arts.

In the face of being labelled irrelevant and conservative, the painted portrait has not only survived, but flourished. It has dealt with the alleged threat posed by photography – and all other technology, for that matter – by simply embracing it. Diversity continues to be its keynote, as demonstrated in the work of such current artists as Gavin Hurley, Mary McIntyre, Richard McWhannell, Liz Maw and Peter Stichbury. Perhaps it is the hyper-real and billboard-scale portraits of Martin Ball that best prepare us for the sculpture of Ron Mueck. But, once again, any similarity may be misleading. At first sight Ball’s close-cropped paintings appear like giant photographs, but on closer inspection they become increasingly fugitive, and lost beneath layers of delicately applied pigment. On the other hand, Mueck replaces two-dimensional metaphor with a more tangible reality in the round. His sculptures remain hard-edged from any distance, and their focus has shifted from the particular to something more universal.

Basil Hallward, the artist at the centre of Oscar Wilde’s 1890 novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, observed: ‘Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist.’ One hundred and twenty years on we may be able to go further, and ascertain that these sculptures by Ron Mueck are also portraits of ourselves.