Not Quite Human

Ronnie van Hout talks to Lara Strongman

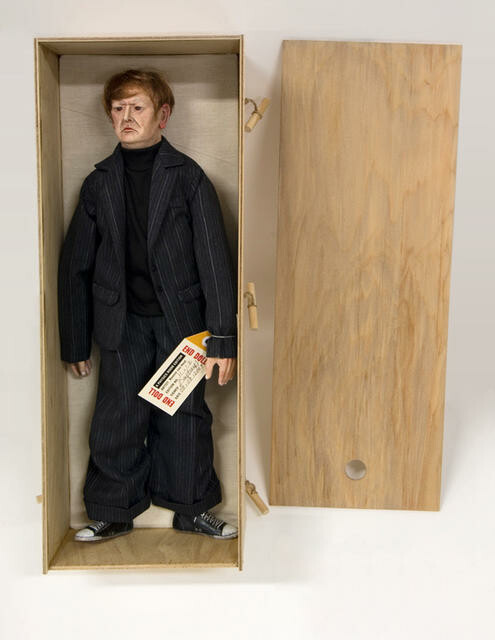

Ronnie van Hout Comin’ Down 2013. Painted polyurethane over VH grade machined polystyrene, glue, welded steel armature. Courtesy of the artist

Lara Strongman: The title of your new work for the Gallery is Quasi. Why did you call it that?

Ronnie van Hout: Initially it was a working title. Because the work would be outside the Gallery, on the roof, I was thinking of Quasimodo, from Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. I was coming out of a show and research around the idea of the freak, the outsider and things that are rejected—thinking about how even things that are rejected have a relationship to whatever they’ve been rejected by. And I called it Quasi, because it’s a human form that’s not quite human as well. The idea of something that resembles a human but is not quite human.

LS: You live in Melbourne now, but you grew up in Christchurch. You’re from Aranui, along with a lot of other extraordinarily creative people; Roger Shepherd, Nathan Pohio, Karoline Tamati, Malo Luafutu, Mark Adams. It’s a special part of town. You’ve made many works that refer to your childhood in Christchurch. I’m thinking of your dad’s shed at Te Papa; House and School, in the Gallery’s collection; Ersatz (Sick Child); and lots more. Can you talk a little bit about your experience of growing up here, and how it informs your work?

RvH: It’s hard to talk about your own personal experience. You have nothing to relate it to. The childhood you have is a closed space. It’s the eternal; childhood doesn’t change. You can go back and revisit it for that reason. I think it was only when I went to art school that I realised that other people had different childhoods to myself. Because that’s your first experience of being outside your own sphere. It’s also related to the type of child I was – my experience of the world and how I perceived it. I do think that Christchurch as a city probably had a big part to play in forming my feeling of my place in the world. Because it’s a such a flat city, you have a very horizontal, flat view of the world. The sky’s very dominant. You certainly have a feeling that you’re on the earth, and that contributes to the feeling of being small. And I think that must have had an influence on me in terms of my interest in UFOs and things coming from the sky. A strong sense that there are odd things in the world that you couldn’t see, but which are affecting you – forces beyond. That’s the kind of child I was.

Ronnie van Hout Comin’ Down 2013. Painted polyurethane over VH grade machined polystyrene, glue, welded steel armature. Courtesy of the artist

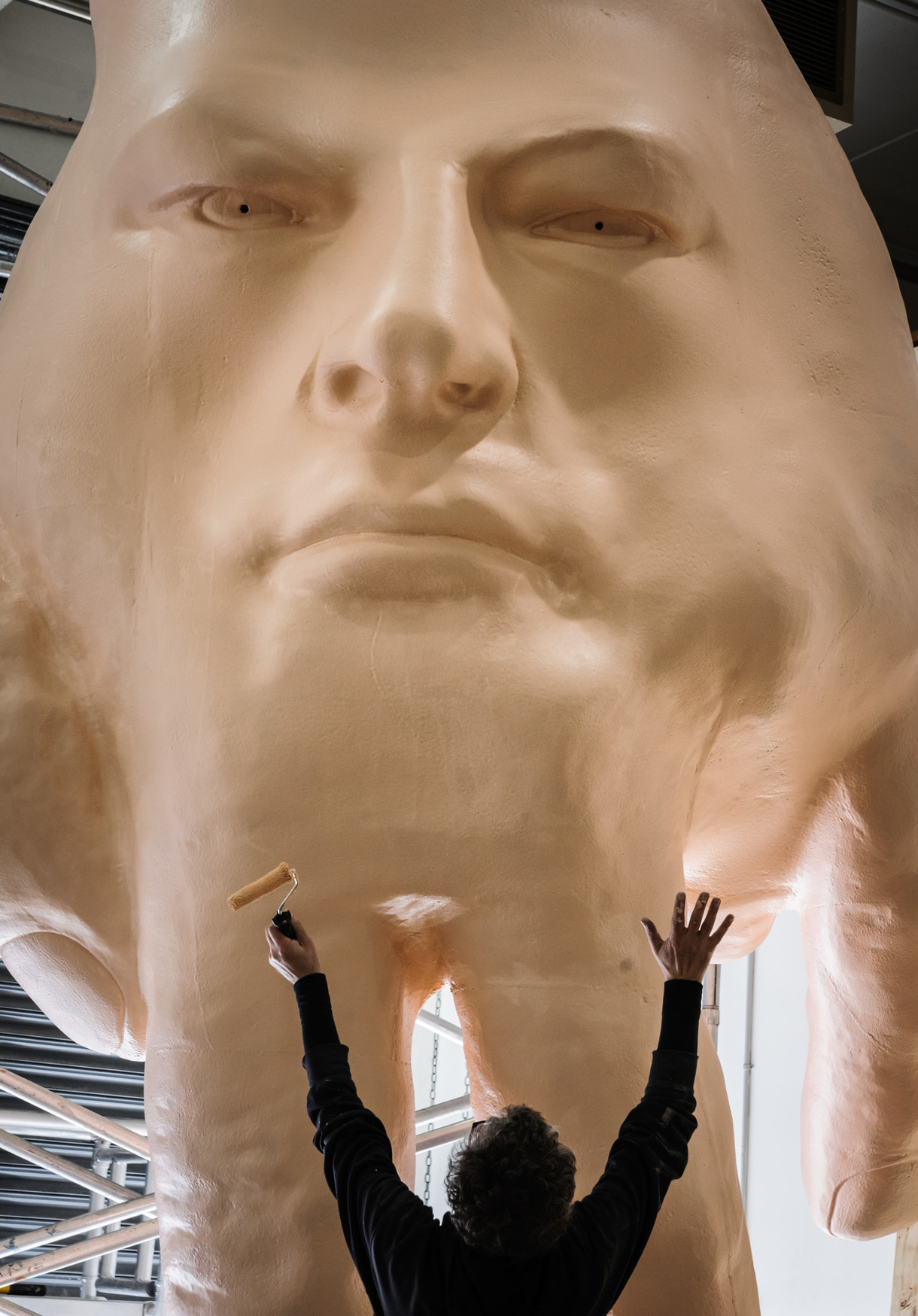

Construction of Ronnie van Hout’s Quasi (2016). Steel, polystyrene and resin. Commissioned by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Courtesy of the artist

LS: Does Christchurch have a distinctive kind of culture?

RvH: Christchurch is an introspective place. There’s a darkness to it, and a coldness. That’s kind of historical; the type of people that settled here, a sort of Protestant thing. People wear black, look a bit dour, unemotional – I will not be affected by happiness or sadness. But that’s an act, a way of performing. I always felt that pressure as I got older. The restrictions that were imposed, not by yourself, but from outside. It relates to the New Zealand past. There’s a coolness, but also, don’t show off. Why would you want to do that. Don’t put your head above the wall… because if you do you’re a show-off or a poser. I grew up thinking about how this held people back. At the same time, Christchurch historically has a very strong tradition in the arts – music, visual arts, writing. And that’s especially true with popular rock music; it’s had a huge history, the strongest in the country I would say.

LS: It’s very much about not making a spectacle of yourself. But actually, your work continually makes a spectacle of your self. You’ve taken that restriction, that cultural limitation that you see in the city, and inverted it.

RvH: Though I don’t really see it as myself. Tony Oursler talks about David Bowie and the performed personality... It is you, but it’s not you. You create this other person that you perform with, and under. So I never really have a lot of personal relationship with it. It’s a sort of performance. And a kind of disembodied personality.

LS: A stand in, or a surrogate for you?

RvH: Yes. Or for someone else. Someone who is me but not me at the same time. It’s a form of acting. A kind of masking. It always comes from somewhere else. Your personality is formed through your relationship to other things, or other people, usually. That’s why I was interested in childhood and revisiting sites of the past. But in the visual arts, things just stand for things, they’re not the actual things, they’re just in-place-of. It’s very complicated today. There’s another layer added... You’re pointing to something that points to something else.

Installation of Ronnie van Hout’s Quasi (2016). Steel, polystyrene and resin. Commissioned by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Courtesy of the artist

LS: One of the things I enjoy about Quasi is its quality of comedy-slash-horror. It’s like a giant prop from a B-movie, something Roger Corman thought better of. It’s less scary than it is funny, but the funniness tips sideways into pathos. This comedy/horror thing is something you’ve often been drawn to. I’m thinking of those photographs from the mid 90s with the low lighting and the block letters rising from the blasted landscape. There was one called The Living Dead, referencing the Romero film as well as, I think, the situation of New Zealand art at that moment. What is it that interests you about the comedy/horror thing in particular?

RvH: I’m interested in film, I guess. Comedy and horror – they deal with the same things… the outsider, the concept of outside. The horror and the monsters are the projected fear of our bodies being destroyed. Classic horror films are to do with home invasion – the classic set up is that life’s normal and happy and something comes along to disrupt that, then it returns back to normal, but there are clues to say it could happen again at any moment. There’s something in the house… We’ve traced the call! It’s coming from inside the house. Chaos ensues. It’s not the stranger but the thing inside that we’re trying to stop. It’s unresolved stuff from childhood; and I think art is an outcome of dealing with those things. We make art because there’s a gap we can’t solve, that language can’t deal with, that we can’t communicate in other ways. It’s like poetry: it exists because it heals language, heals the damage of existence. It’s also why we have to sleep. We externalise an interior state. So Quasi – it’s the idea that monsters aren’t always bad things.

LS: But the idea of the disembodied hand in films… It never means anything good when the disembodied hand turns up.

RvH: That’s what we fear the most. But it’s become quite standard. I remember any time I mentioned zombies in my work, I’d get heh heh heh [mimics pompous laugh]. But now it’s standard. That Living Dead thing, imagining McCahon and Lusk – they are the living dead, they wander our landscape. It was hard to even look at the landscape without imagining them there. They don’t have that effect any more, but at that time they were so huge, kind of monsters.

LS: Do you feel those ghosts are laid to rest now?

RvH: They’re part of some other world. Their discussions are about something else. They’ve become historical.

LS: Today’s view of history seems flatter than the old. Michelangelo is the same as McCahon or van der Velden, they’re all historical and therefore equivalent.

RvH: Time is not a line but a circle. It’s around us.

LS: The individual stands in the middle of each of those circles. Whereas we inherited the canon, that sense of history as a line with us at the end.

RvH: Yeah, but that canon had only recently been put in place when we were at the studying age. It was only people within the art world who were trying to canonise McCahon. And even in the art community, not everyone liked him. He was still being ridiculed.

Construction of Ronnie van Hout’s Quasi (2016). Steel, polystyrene and resin. Commissioned by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Courtesy of the artist

LS: I was re-reading an interview you did in the 90s with Robin Neate – the Hangover interview. You talked about feeling unable to fulfil the concept of yourself as a genius artist, and instead taking small steps, doing small acts. That would be the course of your work. Quasi is a pretty big act, but in a way it’s a small gesture.

RVH: It’s something small made big. It’s a simple idea, and I’ve built towards it. It seemed logical, it seemed like the right thing. But that comment – which I still sort of believe in – came out of thinking about the generation of people I went through university with, grew up with. Not being able to find a place within the art system, which at that time seemed not to include you. And not just because you were young and unknown, but… there wasn’t really an obvious road. There was a lot of mistrust of what we would have considered the old world, the idea of the genius and the masterpiece, which was the way they still talked about art – that just seemed to be impossible. How could I, simple me, ever become that? So there was a sense of not even trying. Certainly the music scene was a bit like that as well. Everyone was making these terribly complicated expensive studio albums, and there was no point in

attempting to do that – you’ve just got to make art for the community that you’re in. When I reflect on it now, people shared similar goals. One of them was not being big time; it was always about the local. Taking apart the hierarchy and levelling it out.

LS: How does Quasi relate to the previous rooftop work you did in Christchurch, on the old Post Office building?

RvH: Maybe it’s the hand of the pointing figure that has detached, flown across the city, and landed, superhero-like, on the roof of the Gallery. Gestures of the hand are being read as a form of language; and the hand has become the centre of speaking and taken on the language of the head. Merging the two together. I see hands everywhere now in art. Also it’s how we read the body and understand it simply. It’s those things we understand without thinking that are interesting. That relates to the idea of the alien and how centric we are. We always interpret things from our own position – it’s impossible not to. We see the hand, and the fingers become legs – it’s easy to read them like that. I made a video of some hands walking around to test it. It plays with empathy as well. You can project into it.

Installation of Ronnie van Hout’s Quasi (2016). Steel, polystyrene and resin. Commissioned by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Courtesy of the artist

LS: Empathy is an emotion that runs through your work. It’s funny; but with a vein of sadness and pathos. Something to do with the sense of not being quite adequate, or being subordinate, or wanting to do something but not quite being able to say it or reach it or do it.

RvH: Which I guess is a sense of failure. Or aspiration that falls short. Failure is a big part of art; a big part of life, or existence. I don’t go along with the idea of the artist as a producer of perfectly finished forms and high production values. My process is still studio-based; it’s still me, working on things, and all my inadequacies at doing that. I’m not particularly interested in outcomes. I’m more interested in the things that I learn as I’m making.

LS: What have you learned from this one?

RvH: The ideas of the gesture – and that you can empathise with your hand. That other people can connect to it. It puts you in a weird space. I like to do that in terms of art; it puts you in between adulthood and childhood, between being in control and not. The hand is the device of control that we normally associate with handling things. Dealing with stuff. Then you subvert it by creaturising it and it suddenly becomes a bit more chaotic and less controllable. Something like a monster.

LS: But because it’s your hand, it’s also the hand of the artist. So the alien hand that’s flown across the city and landed on top of the Gallery and is silhouetted against the sky, that’s also an artist’s hand. It points to the idea of creation – and the hand as the source of the artist’s genius. The point from which the mark is made.

RvH: And anyone who’s ever had to make anything knows that that’s where failure occurs, between here [points to head] and there [gestures with hand]. The brain visualises something and you try to make it happen. But then there’s a bit of a gap. Between thought and expression, as the Velvet Underground would say, lies a lifetime.

Lara Strongman talked to Ronnie van Hout in Christchurch in June 2016. Quasi will be on display on the Gallery roof until mid 2017.

Ronnie van Hout Quasi 2016. Steel,

polystyrene and resin. Commissioned by

Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū.

Courtesy of the artist