B.

What sort of city do we want our children's children to live in?

Comment

Martin Trusttum, project manager for Ōtākaro Art by the River, and founder of temporary gallery space ArtBox, writes on the role of art in Christchurch.

There was a groundswell of collective energy following the Canterbury earthquakes; a culture of collaboration and possibility that was unrivalled in a town where, in the main, we had preferred to go it alone. There was a palpable sense that we could lead the way, off the back of such widespread devastation and tragic loss, to a more inclusive, collaborative and positive place.

We each felt in our own way like architects of destiny and we truly believed that what we thought, dreamed, imagined, could materialise. There was a sense of urgency and nerves and promise in those early days, which was ultimately distilled into a clear, shared objective to connect people with each other and to our new environment.

Individuals and communities forged alliances and both offered and provided support, which led to a great deal of discussion but also, importantly, to a lot of productive activity. And the arts were not simply an example of this phenomenon but a catalyst for it. People believed art could make a difference; bringing people together to share, to grieve, and to begin to heal.

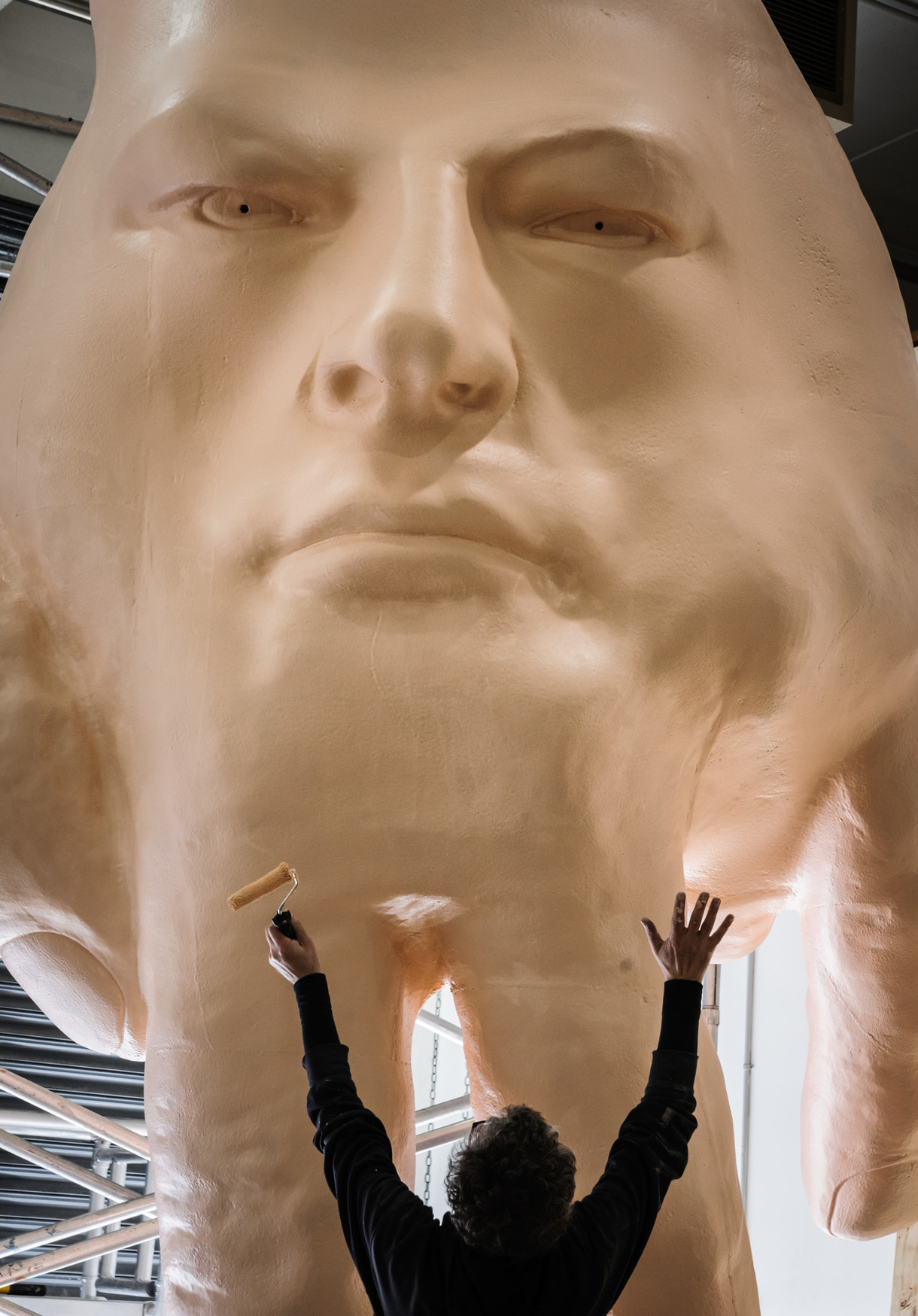

Consequently, the arts and artists received support from industry and corporates, institutions and organisations on a scale that hadn't been seen before in Christchurch. Artworks appeared across the city like random expressions of optimism and people from all walks of life began to respond.

Art galvanised the people of Christchurch at a time when the only other conversation was loss. A perfect example of this phenomenon was the number and diversity of people who embraced the RISE and 'Oi You' events. Here we had street art—a niche, post-graffiti art form with roots in social and political protest—presented in a museum and on numerous walls across the city drawing the single biggest audience an art event in this city has ever seen. It was astonishing and heartening and completely inspiring. Art was front and centre and people loved it.

But as time passes and our city slowly regains a more solid form, the once shared collaborative objectives are facing the perils of fatigue, habit and pragmatism.

For the local arts community that only yesterday rode the wave buoyed by popular enthusiasm and support, the challenge is twofold: to nourish the shared objective, the collaborative purpose, the unique enthusiasm that hatched in 2011; and to keep the local community engaged not just as an audience, but as conscious participants in the arts. And the challenge for our city is to make the link between them.

We know the value of the arts, especially public art, is always loudly debated and when compared to infrastructure, services and amenities, is generally ranked as being of lesser importance. However, the earthquakes made clear to me that people value an item for its emotional association often as much as they value one for its functional benefit. We hold things close to us as reminders or signifiers of associated memories and hopes. The flourishing of arts in the public realm after 2011 seemed to respond to the same need to build emotional links with and within our new landscape.

The American psychologist Abraham Maslow might agree that the arts are less important in a 'hierarchy of needs' than infrastructure, but I don't believe it's a competition. The arts are very rarely at the expense of infrastructure in our modern environment. An investment in a public work of art does not mean a sewer line won't be repaired, or a road resurfaced; it doesn't necessarily follow that a hospital bed or an additional teacher won't be provided. The funding for such projects is not interdependent.

People need a rich network of associations and links to feel happy and safe—to thrive. We clearly need to meet our physical needs, but as human beings, we have emotional needs too. Art, in the broadest sense, goes a long way towards expressing and satisfying this emotional requirement.

To anyone that argues this is not the case I would say remove all the non-essential, arts related activities from your lives and tell me what sort of life you lead. Imagine if there was no drama—no school productions, no Sparks in the Park, no Buskers Festival; no music—bands or orchestras so no radio apart from talkback; no dancing (or dance classes); no festivals at all. And then, to extrapolate further: no theatre, no films, no books, no magazines, no video games, no sculpture or decoration in our parks, or on our streets, or in our homes.

And to those who would maintain that these have no relationship to our wider lived experience, I can guarantee this isn't the case. Artists are interpreters both of their own situation and the context they inhabit. They identify and address problems or interests in their own way. They appropriate influences, ideas and concepts from any source that seems relevant and in so doing develop, extend, and reframe conversations over time and distance—conversations that affect all of us and enrich our lives. Their influence extends to other artists, designers, architects, engineers, to the automobile and technology industries, to the world we all share.

The arts for example are typically used in the commercial context here in New Zealand to add the zing a developer couldn't capture in one of his/her developments alone, and most often as an afterthought. The project and the artwork both pay a price for this.

Putting the arts at the centre of any debate about the city's growth is part of a long-game plan and is the hallmark of a mature culture. But the arts need to be included at the genesis of the process. The collaborative development of the arts and the built environment ensures that we inherit public spaces we are both proud of and wish to inhabit. This should be the goal we all have in mind and it's a very far-reaching goal. We need to be thinking fifty years into the future, 100 years even, and asking ourselves: what sort of city do we want our children's children to live in? If we do this I believe we will come to see that the arts will need a seat at the planners' table. Today.