A Dark and Empty Interior

Antony Gormley Event Horizon 2007. 27 fibreglass and 4 cast iron figures, each element 189 x 53 x 29cm. Installation view Hayward Gallery, London, 2007. A Hayward Gallery Commission. © the artist. Photo: Richard Bryant

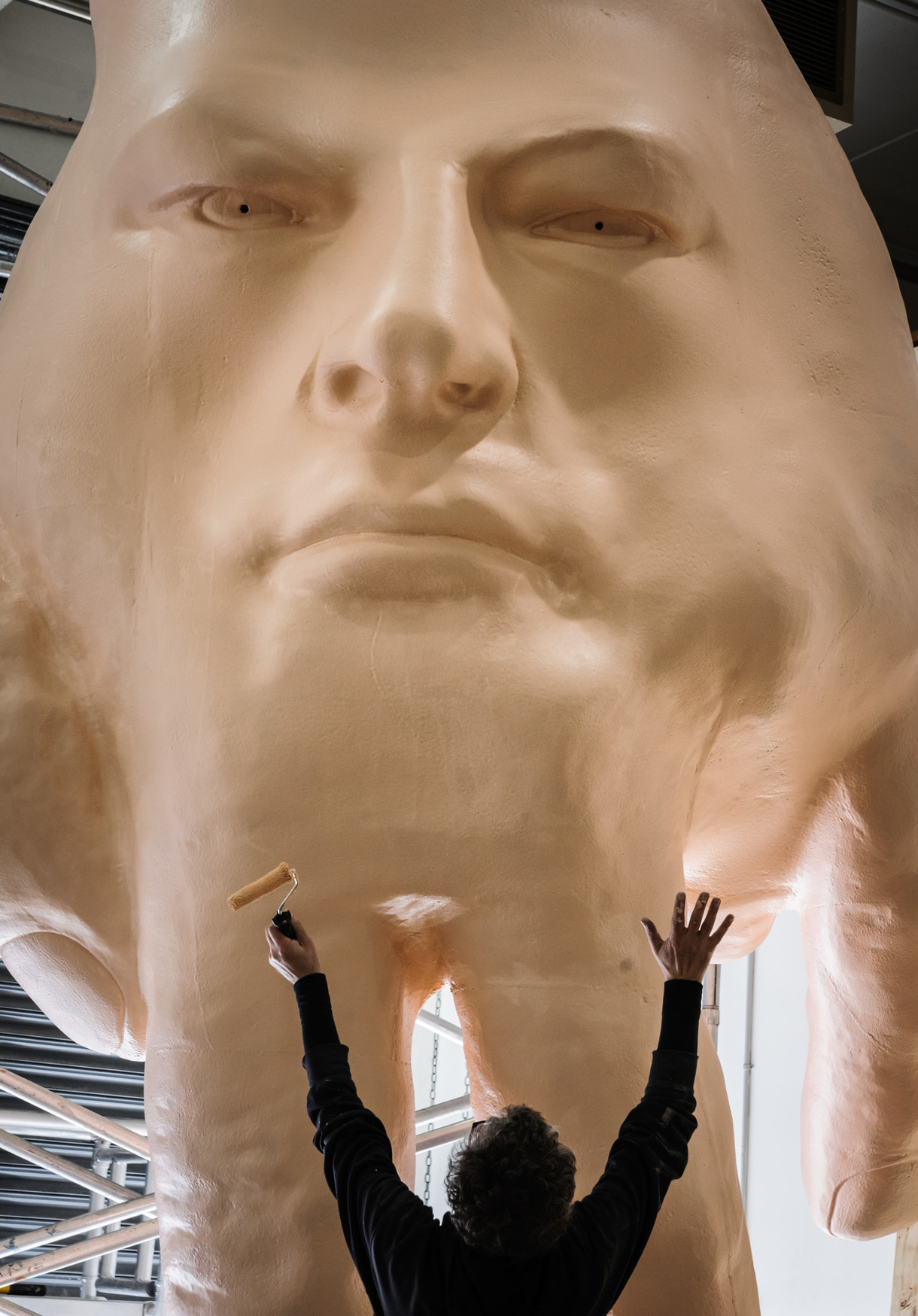

In B.167 senior curator Justin Paton documented his walk around the perimeter of Christchurch's red zone, and we featured the empty Rolleston plinth outside Canterbury Museum at the end of Worcester Boulevard. In this edition, director Jenny Harper interviews English sculptor Antony Gormley, who successfully animated another vacant central-city plinth—the so-called Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, London. Gormley filled the plinth with 2,400 people, who occupied it for one hour each, night and day, for 100 days. Here, Jenny asks him about his practice, the value of the figurative tradition and whether he has any advice for Christchurch.

Jenny Harper: I'd love to capture some of your thoughts about Christchurch, but first I thought we'd start by exploring your own work and gaining some insights into your practice. From the 1980s at least, the body is always present—actual or implied—even, it seems, when it's abstracted. And I wondered why this very traditional subject in art history has held such fascination for you over all these years?

Antony Gormley: I don't think I had any choice really. My trajectory into working with things was first being a fairly proficient drawer and painter at school and winning art prizes and then going on to travelling. I went to Cambridge because I got in—nobody could believe I would—and I did anthropology and archaeology and then history of art. I knew I didn't want to become an academic, but I wasn't confident that I would be an artist and I wasn't sure that I wanted to be one anyway. So I went to India for three years—well, two years there and a year getting there. I suppose that's a rather long way of saying that my return to art happened quite late and an interest in the body even later. Certainly in Goldsmiths and at the Slade I was working with materials that were not figurative. I wasn't imposing form on them but discovering an inherent form.

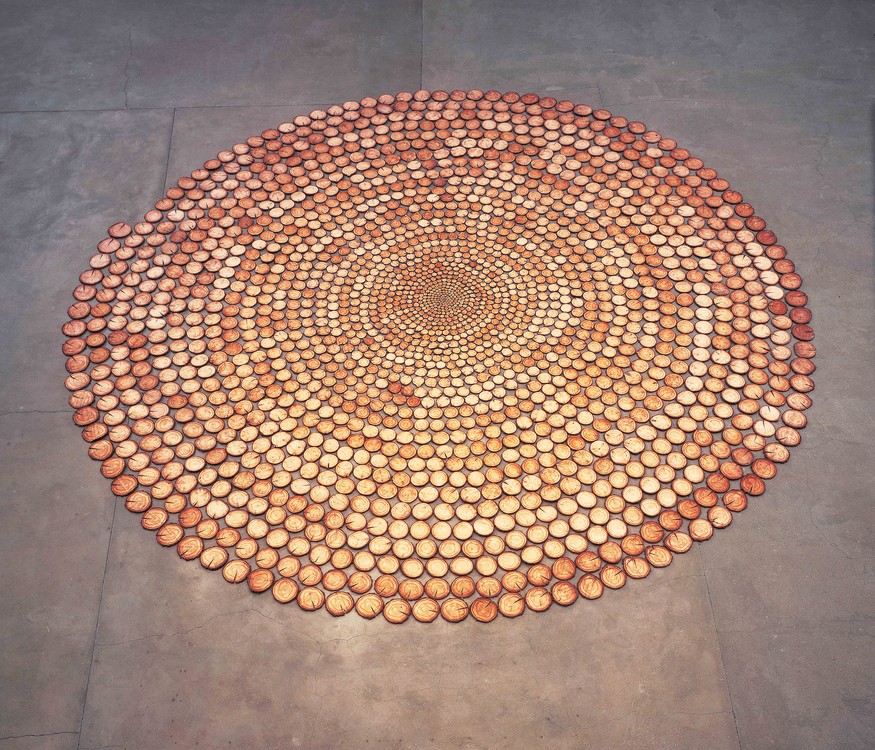

Flat Tree is a good example of that: a thirty-year-old pine tree carved into slices and then laid out in a spiral so it made a map, which also became a strange optical thing in which space became curved and disappeared down to the tiny discs in the middle. It was a way of seeing the time in an object. And Rearranged Tree was another example: a thirty-year-old pine arranged in thirty piles of little discs from one to thirty. Both of these were exhibited during my time at the Slade, and they were about examining the world around me in material terms and then allowing it to re-present itself. When I made Bread Line—a whole loaf of Mother's Pride laid out a bite at a time—here was a daily object somehow re-described in the way that it was physically experienced. I think that work was the beginning of my thinking about the processes of living, and that led me back to the body. I started out looking at rocks and trees and ended up looking at things and materials that were immediately connected to the intimate life of a human body, like clothes and food. I had been using bread as if it was a sheet material and cutting it with a marquetry saw, but it was really much more sensible to use my teeth...

Antony Gormley Flat Tree 1978. Larch wood. © the artist

That may seem like an extraordinarily backwardlooking way of returning to the body but, having looked at matter within history's intrinsic time and at how time had inscribed itself within matter, I was simply thinking about what the primary relationships with matter were. I was looking at glacial erratic rocks as well and did some analytical work, but I guess I went back to the body because I was trying to deal with real things, with first-hand experience.

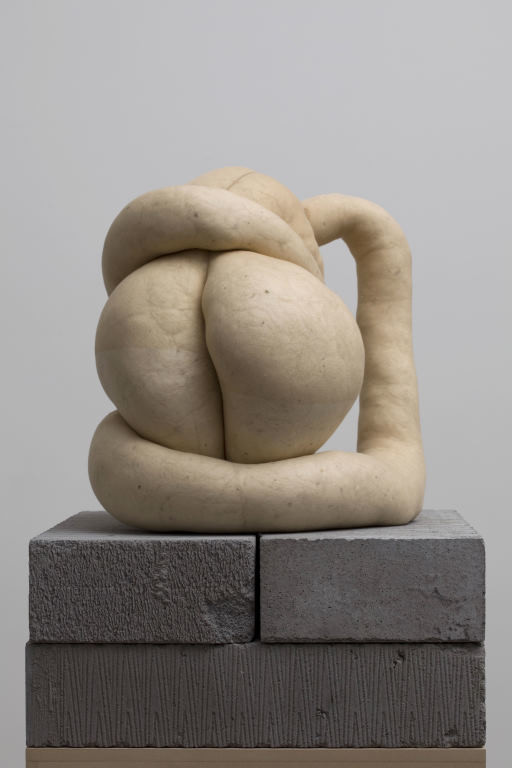

I've said this numerous times—I didn't want to start with the body as a given, I wanted to start with the body as a site of experience. I didn't want to start with the body as an image or as a figure. I think it's very important that the work is about the body, not about the figure. I am not putting the figure to work. Having had a protracted training with the historical, philosophical, meditational and then the physical in the syntax of art generally, and realising how much was so concerned with form and conceptual issues that were unique to the artworld, I wanted to deal with life or something much more connected with the real, whatever that means. So I made Bed, which was, I suppose, the first time in my early work that the body was actually figured in some way or acknowledged—that was the 600 loaves of Mother's Pride out of which I ate my own volume over about a three-month period. Concomitant with that I made Room, which was a set of my own clothes cut into continual strips and expanded to fill a room about twenty-foot square. Between Room and Bed I had identified the place of the body, so the next question was how to begin to deal with the body in a fresh manner; not as it were, where Rodin left off, but as a system, as a transformative place. In King's Cross, where we were squatting at the time, I made the first of the body moulds; that was called Mould and it was a mould and it still is a mould. It's a lead mould of my body, with the mouth I used for breathing open as it was open. It connect with Bread Line and withBed—here is the orifice, a bridge between body and earth that allows life.

And then I thought about that more and made Hole, which is the anus piece, and thenPassage—the one with the erect penis. I guess this was really just looking at the body as a site of transformation, looking at its entrances and exits and its primary connections with the material world, and that started me on my way. It's odd—when Vicken, my wife, moulded me for the first time I would never have dreamt that I would still be doing it thirty-one odd years later. I mean, I've got to find a better way of leading my life...

Antony Gormley Three Ways: Mould Hole and Passage 1981–2. Lead, plaster. Installation view, Tate Gallery, London. Tate Gallery Collection, London. © the artist. Photo: Tate

JH: You mentioned Rodin and whether or not to continue with the tradition he established. What is the value of that tradition?

AG: Well I don't know whether I am continuing it. I am very keen to acknowledge that the body has been in art as long as it's been conscious, but I would like to think that my work is a radical re-examination of what a body is. The value of the figurative tradition is little. I don't think of myself as making work in a tradition—I am a conceptual artist who has returned to the body because it is the site of being, of human being. I'm not interested in tradition for its own sake.

That doesn't mean to say that I don't admire some figurative artists from the past, but I want my work to be compared with the work of Richard Serra, Carl Andre and Walter de Maria rather than with figurative sculptors. It's very upsetting to me at the moment that my work is on show at Tate Britain next to an Epstein and a golden male figure by Leonard McComb: an acknowledgment of failure in my view. My intent is to give form to the truth that we all live at the other side of appearance. The work at Tate Britain is an untitled work, a standing lead body case made in 1985 with piercings in the position of the stigmata referring to St Francis. But those five stigmata points are transformed into eyes or eye-shaped holes that give access onto a dark and empty interior. And that is my subject. My enquiry is: what is a human space in space at large? The fact that it has a human form is an accident.

You could say the human body is my found object; equally it's the lost subject of modernity. Mondrian rejected the body, I have a great interest in and respect for Mondrian and the principles that he developed for a pure art of contemplation. I would like to think that my work also uses principles of stillness—the abandonment of unnecessary gesture, of movement, of narrative—in order to engage in the body as a place, not a thing.

JH: You mentioned your time spent in India, and it's interesting to consider how images of the Buddha are valued for their very conventional and recognisable form but are pure in their simplicity— totally without that sense of artistic renewal that we value so much in the West.

AG: It is interesting isn't it. I love Gupta art, and Gandharan sculpture is interesting because of its interplay between Greek traditions and those of the subcontinent, but I think that for me the Belgola Jain image of a tirthankara or the Chola and Pala bronzes from South India are the high point of Indian art. It's to do with the invention of an abstract body. I think that in contrast to, say, the sex and death theme of the Western trajectory—the desire to produce either a narrative or heroic art—the Buddhist trajectory is one of highly conventionalised, proportional rules, a made body that has very little to do with a perfect copy. Yet, through that, notions of timelessness and I suppose samadhi or concentration, an embodied void or sunyata is conveyed and I have found great empathy with that.

But I'm not making votive images for a religion that doesn't exist. I'm trying to do for the body what Mondrian did for painting; liberate it from all of the burdens it has had to carry.

Antony Gormley Event Horizon 2007. 27 fibreglass and 4 cast iron figures, each element 189 x 53 x 29cm. A Hayward Gallery Commission. Presented by Madison Square Park Conservancy, New York, 2010. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, New York and White Cube, London. © the artist. Photo: James Ewing

JH: I think that's a good moment perhaps to mention Rosalind Krauss's Sculpture in the Expanded Field, and her assertion that sculpture has detached itself from the plinth and become nomadic. I'm wondering how your work has engaged with the idea of the figure in the world?

AG: Passages in Modern Sculpture, that's a Biblical text. Rosalind may have gone her own way since then, but certainly for me growing up as a sculptor it was a critical text in many, many ways. Her engagement with Merleau-Ponty, phenomenology, the legacy of Husserl and Heidegger, the idea of sculpture as a medium of first-hand experience and indeed the way in which she posits sculpture as the most radical force in art... The reason I came back from India was to make things that changed the world; to do what she suggested that sculpture could by being an object in the world and not being a representation, by being a thing in itself, by being a self-referential displacement of the way things were. To change the way people saw, thought about and related to the facts. In considering the object you are forced to reconsider your own relationship to the world and that's one of the key reasons that I attempted to reconnect with the taboo subject of embodiment, because I thought this was a tool that could be used for awareness. At the same time, from very early on, I wanted to put the work directly into the world rather than having it mediated or framed by institutions or the conventions of an exhibition.

I believed in the expanded field; I grew up in the sixties, took part in happenings. I was involved with dance and performance and got a lot of inspiration from it, whether it was Trisha Brown or Fluxus. And with the spirit of that work comes the idea that an artist doesn't need the validation of institutions. You can work directly in the world, even if your work is as internalised as my performances are. My work comes from performance but it is a very internalised performance.

Antony Gormley Event Horizon 2007. 27 fibreglass and 4 cast iron figures, each element 189 x 53 x 29cm. Installation view Hayward Gallery, London, 2007. A Hayward Gallery Commission. © the artist. Photo: Richard Bryant

JH: Thinking about the settings and contexts for art and your desire to place works outside the institutions, let's talk about Event Horizon. I was very lucky to see this both in London and later in New York, and was so impressed with it—and its different receptions—in both cities. Because people were interpreting its figures very differently— in New York they seemed rather worried about whether or not someone was about to jump. How crucial a part does the given city play in a work like that? How does the work become a source of intrigue or inspiration within a given context?

AG: Well the figures in Event Horizon are literally foreign bodies aren't they? They are nameless and placeless things that you bump into on the street or see on the skyline; the antithesis of the plinth and the titled public statue. For me, putting these bare bodies in the street and in the sky in these key urban sites was a way of asking the question: what is a human space within space at large in a site of dense habitation?

Event Horizon is nomadic. The bodies come one day and are gone the next. I always thought of them as like benign watchers, the ones who could see a horizon that was lost to us walking in the chasms between the cliffs of a built world. But in New York certainly the typical response was that this was freaky and do to with death.

JH: So it's revealing about the cultural context into which these things are placed.

AG: That is important to me. This is to do with what I think of as a changed function for art. To a degree, art has to be adequately empty and silent in order for it to work as a focus for the projections of the public. I don't mean to say that I don't have ideas about why I'm doing it, but I do think that these things are acupuncture—in their disruptive or provocative presence they release latent energies which can be quite dark but this is a necessary and good function for art.

Antony Gormley One & Other 2009. The Mayor's Fourth Plinth Commission. Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London, England. © the artist

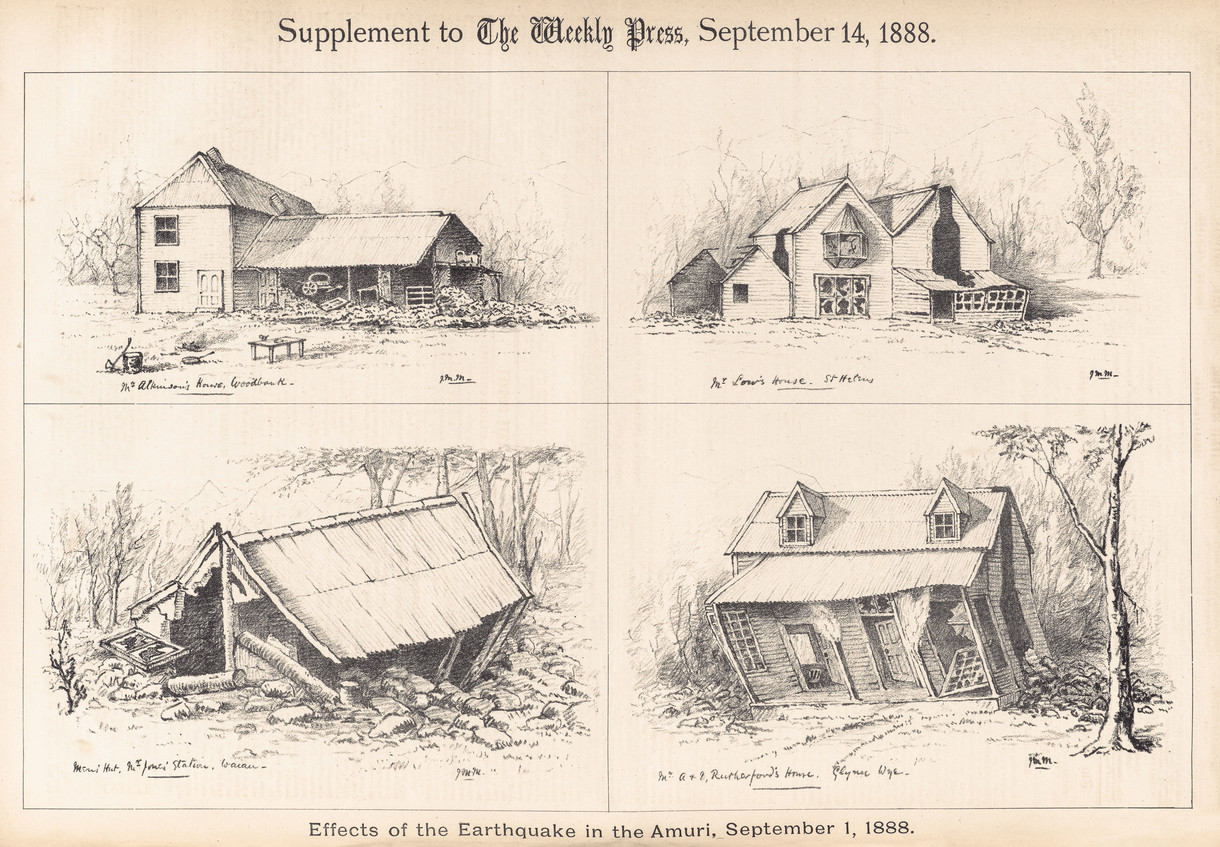

JH: It certainly is. So shall we turn to Christchurch, where obviously issues of permanence and impermanence are paramount at the moment. We've had a number of important public works which have literally toppled from their pedestals and a range of significant buildings lost. Just to give you a sense of the scale of the demolition, within a few months, the inner-city block on which our art gallery stands will only have two other buildings on it. The whole of the city is so dramatically changed. It was pretty empty before in many respects and not all was perfect, but obviously we've now got an interesting chance to rethink living and working in the inner city. What role do you think art can play, both in helping the grieving process and also in a post-disaster environment?

AG: Well, it's an old cliché, but in every disaster there's opportunity. I think this issue of how memory can be reconciled with anticipation and the rightful joys of renewal is important because, as is so often the case within urban environments, there's a reluctant acceptance of city plans or the grid or the relationship between public and private. But I'm very sorry about what happened to Christchurch. I was there once and my memory is that it was rather blessed with open spaces and relatively wide streets and no great high-rises, so it was a generous and a fine example of a demographic space where there was, I think, a nice dialogue between commercial interests, civic institutions and dwellings.

But the opportunity is to get artists themselves involved in the re-imagining of what the collective life of the city should be and how to balance that with the necessary acknowledgment of this particular tragedy. Maybe we could then think about how the rather disparate languages of what is left by an unplanned historic remnant could become more focused.

I found myself wondering what will happen to the sculpture of Sir Robert Falcon Scott and whether he can be brought down from his plinth to live with us on the ground as a fellow companion. He suffered his own disaster, didn't he, but he's still a fantastically powerful figure and could become part of life on the street. Maybe it's an opportunity to think about how he could be combined with another idea of possible futures. What motivates explorers is a very powerful idea and human beings need continually to reimagine what's possible. We should be aware of how powerful the reimagining of what's happening in Christchurch can be.

In London, for example, the twentieth century was utterly hopeless in providing new forms of public space that represented the changes in a liberalising democracy. We're really lucky to have our squares and parks and civic spaces here, but they were all determined in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. If you consider the High Line in New York, however, here is a completely new kind of public space in which engagement with the past and the present happens in equal measure. It informs its views onto the West River and onto buildings that you don't normally see from the outside at that height. And there are all sorts of really lovely opportunities for social engagement, people reading the newspapers on loungers, running, chatting, taking their dogs for walks or walking by.

I think we need to think in a new way about how people like to live together in towns and this is a good opportunity to do so.

JH: Is there anything else you'd like to say about city spaces? Of course, I think about the power of the Fourth Plinth project in Trafalgar Square, an extraordinary intervention in London.

AG: Well, I think all spaces invite a certain kind of inhabitation and we need to continually reinvent them. So this is an exciting time for Christchurch. It can completely reinvent itself in a way that could become an example to the rest of the world. You know, there's no question that human futures are going to be determined by cities. We've passed the point where over fifty per cent of the human race lives in cities. We know environmentally cities are the lightest per person carbon footprint that we can have.

What I love, and I think the Fourth Plinth project was an example of this, is spaces in which citizens become both the viewers and the viewed. In other words, we create spaces that can be used as instruments by which we look at ourselves again. Washington Square in New York is a good example. So many different activities happen at once—you have skateboarders and frisbee players, along with dog lovers and card and domino players and people who just sit on benches and chat. I think the great Mies van der Rohe space on Fifth Avenue is another example of a fantastic idea of what a collective space could be in the city. And how that then relates to all of the basic pleasures that we have: eating, walking, talking, looking—looking out and looking in, looking at each other and looking at the distance. All of these things need to be reconsidered. At the end of the twentieth century we have seen this massive process of the privatisation of collective space, either through the dominance of advertising or through the literal commercialisation of space. Between advertising and shopping, public open space has been lost to commercialisation, which has a profound effect on how we relate to each other as citizens. It suggests that we only have value as consumers, which is a passive and non-celebratory idea of the citizen.

We need to treasure our parks, our runners and our skateboarders and our BMX riders and the people that in some way animate the city by playing with it. Manhattan's High Line is a very good example of how pleasure becomes a spectacle. And we need more of that. The twentieth century failed, well certainly in London, to give a new vision to collective space—and I'm sure we can learn from Christchurch.