Pip Culbert

b.1938, d.2016

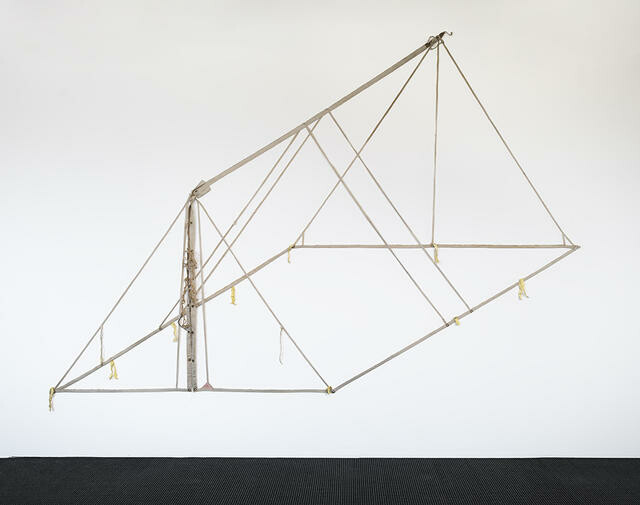

Pup Tent

- 1999

- canvas, metal, rope

- Purchased 2013

- 2400 x 3650mm

- 2013/080

Tags: line drawings (drawings), perspective (technique), tents (portable buildings)

In this deconstructed tent, Pip Culbert has removed everything except the seams. What’s left is like a line drawing, or a plan of a tent at one-to-one scale. Culbert’s work claims space, yet sits lightly on the wall – much as a tent sits lightly on the land while providing a temporary home for its inhabitants. Culbert was a British artist who often exhibited in Aotearoa New Zealand, regularly travelling to visit friends around the country. Her ‘ghost tent’ evokes a sense of movement through, and temporary encampment within, the local landscape.

(Te Wheke, 2020)

Exhibition History

Above Ground, 18 December 2015 – 12 February 2017

The tent, one of the most basic architectural structures, is also a symbol for temporary shelter and a metaphor for the body. Pip Culbert has investigated its essential form by removing everything but the reinforced stitching, laying out its structure like an isometric plan. The tent is denied perspective but retains a spatial sense.

Culbert was a British artist based in France who graduated from the Royal College of Art in London in the early 1960s. Culbert showed her work extensively in solo and group shows internationally, and first exhibited in this country in 1993.

Christchurch Art Gallery acknowledges with sadness the recent passing of Pip Culbert.

Shifting lines, 9 November 2013 – 19 January 2014

Pinned to the wall, Pip Culbert’s diagrammatic tent projects like an isometric plan, denied perspective but retaining a spatial sense. Pip Culbert works with found objects made of cloth, which have included shirts, tarpaulins, flags, pockets, surf sails, trousers, quilts, ties, bags, ironing boards, upholstery, parachutes, aprons and even handkerchiefs. Her technique involves cutting away to remove everything but the bones – the essential, strengthened lines of stitching. In effect drawing by subtraction, this is also drawing in the sense of rendering three-dimensional objects two-dimensional.

Born in 1938, Pip Culbert is a British artist based in France, who graduated from the Royal College of Art in London in the early 1960s. She has shown extensively in solo and group shows internationally, first exhibiting in New Zealand in 1993.