Interview

B.

Bulletin

New Zealand's leading

gallery magazine

Latest Issue

B.21601 Jun 2024

Contributors

Interview

Texture of the Time

John Miller (Ngāpuhi) is a special figure in Aotearoa, having photographed protests and important events throughout the country from 1967 right up until the present moment. His work covers everything from the 1960s and 1970s anti-Vietnam war and anti-nuclear protests to the 1975 Māori Land March, 1977–78 Bastion Point occupation and 1981 Springbok Tour protests, as well as many more examples of civilian dissent. John uses the camera as a witness, capturing moments of collective voice in action, and he also honours the people who have led the charge for changes in thinking and our society. Looking at his work is like walking through our history backwards into the future. Curator Melanie Oliver sat down with activist John Minto and photographer Conor Clarke (Ngāi Tahu) to talk about John Miller’s work.

Interview

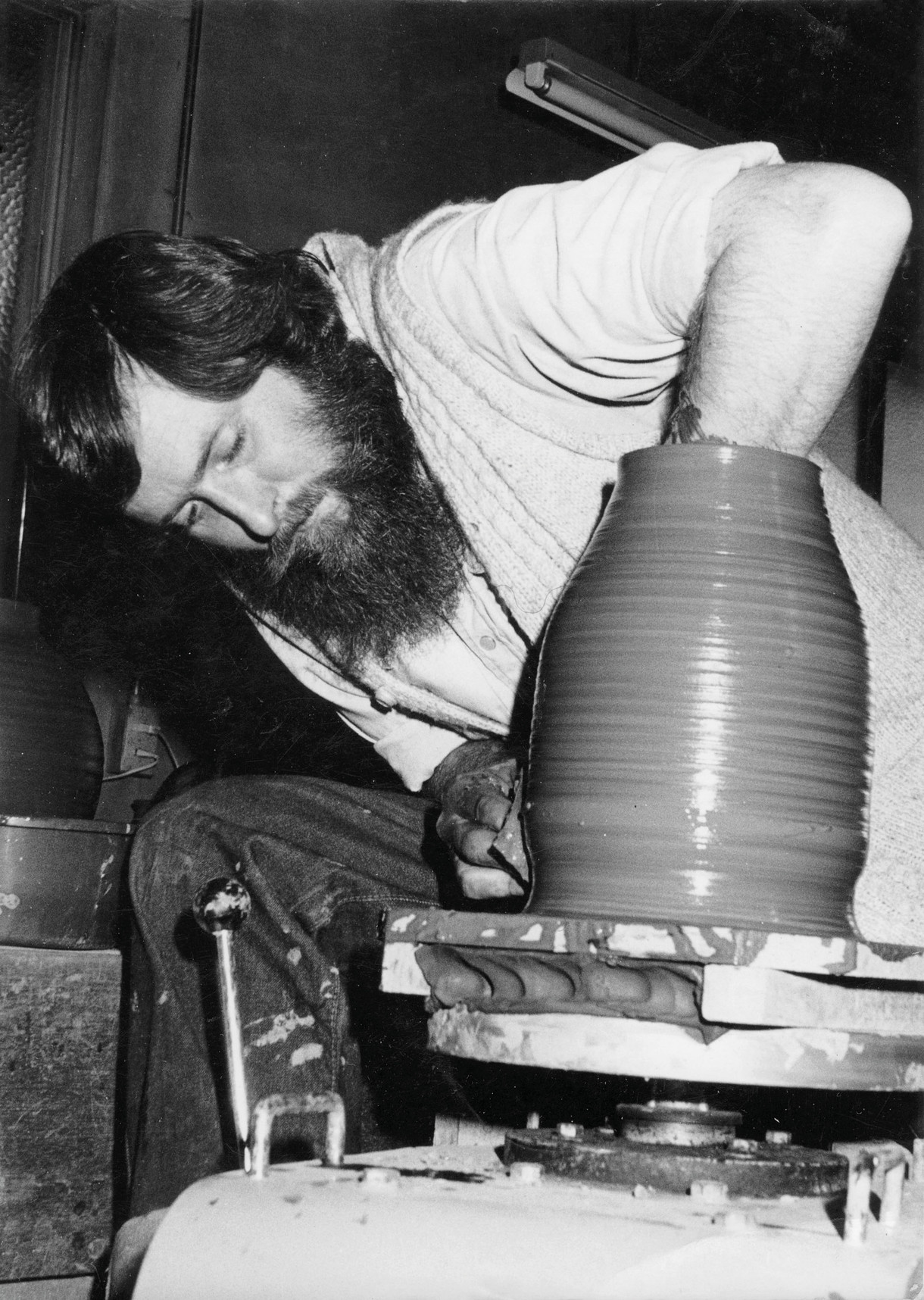

A Passion for Clay and Pots

In recent months, retired potter and former president of the Canterbury Potters’ Association, Rex Valentine – a man passionate about clay – and art consultant Grant Banbury have been working behind-the-scenes in the Gallery alongside registration, curatorial and conservation staff. They’ve been assisting with an audit of a part of the collection that we’re excited to be working with more – the Gallery’s ceramics holdings.

Here Banbury and Valentine discuss the latter’s own production and involvement in pottery circles in Canterbury from the late 1960s to the 1980s; his time spent in studying pottery in Japan, and his involvement with pottery acquisitions during Brian Muir’s directorship of the Robert McDougall Art Gallery. The edited extracts that follow are from an interview recorded at Valentine’s home in Christchurch on 10 April 2021.

Interview

Ka pai e whanaunga

Nathan Pōhio: We’re going to do this whānau styles.

Areta Wilkinson: Totally. We’re going to indigenise the interview process.

NP: Tēnā koe Areta, ngā mihi nui. Your project Moa-Hunter Fashions is primarily concerned with, or comes from, thinking around whakapapa and geological history, so let’s start by talking about that, and how it pertains to what you’re doing in the exhibition.

Interview

Take the ‘A’ Train

Peter Vangioni: It’s late June, and you haven’t been outside for 16 weeks? Is that right? How are you and Barbara coping with the shelter in place order and are you able to work under these conditions?

Max Gimblett: Well, I’ve been out to put the garbage out twice a week—I cross the pavement and come back to the door. Some people are out there walking with their masks. Barbara is super cautious, you know because of our age, we can’t even come close to anybody. But we are doing very well in this lockdown, and have no plans to leave the loft.

Interview

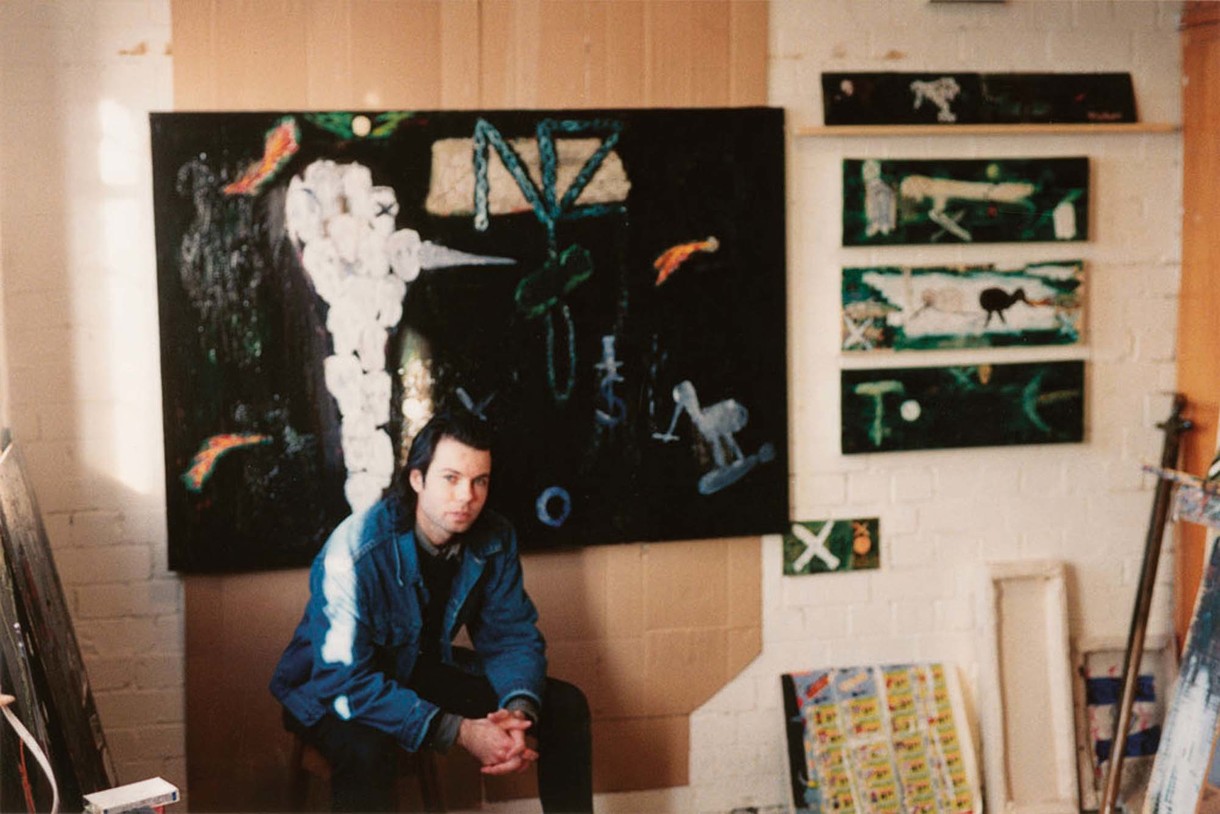

Driving Without a Licence

Peter Robinson: I may be wrong about this, but I believe that we were the last generation to experience the primacy of painting at art school. What I mean by this is that when we were at Ilam, students had to compete to get into departments. As crazy as it sounds now, there was a very clear hierarchy: painting was the most popular discipline and afforded the most esteem, sculpture second, then film, print, design and photography somewhere down the line. Can you remember why you ended up choosing sculpture? And furthermore why you ended up being a painter? Do you think your training as a sculptor affected the way you think about or approach painting that is different to someone who was trained formally as a painter?

Interview

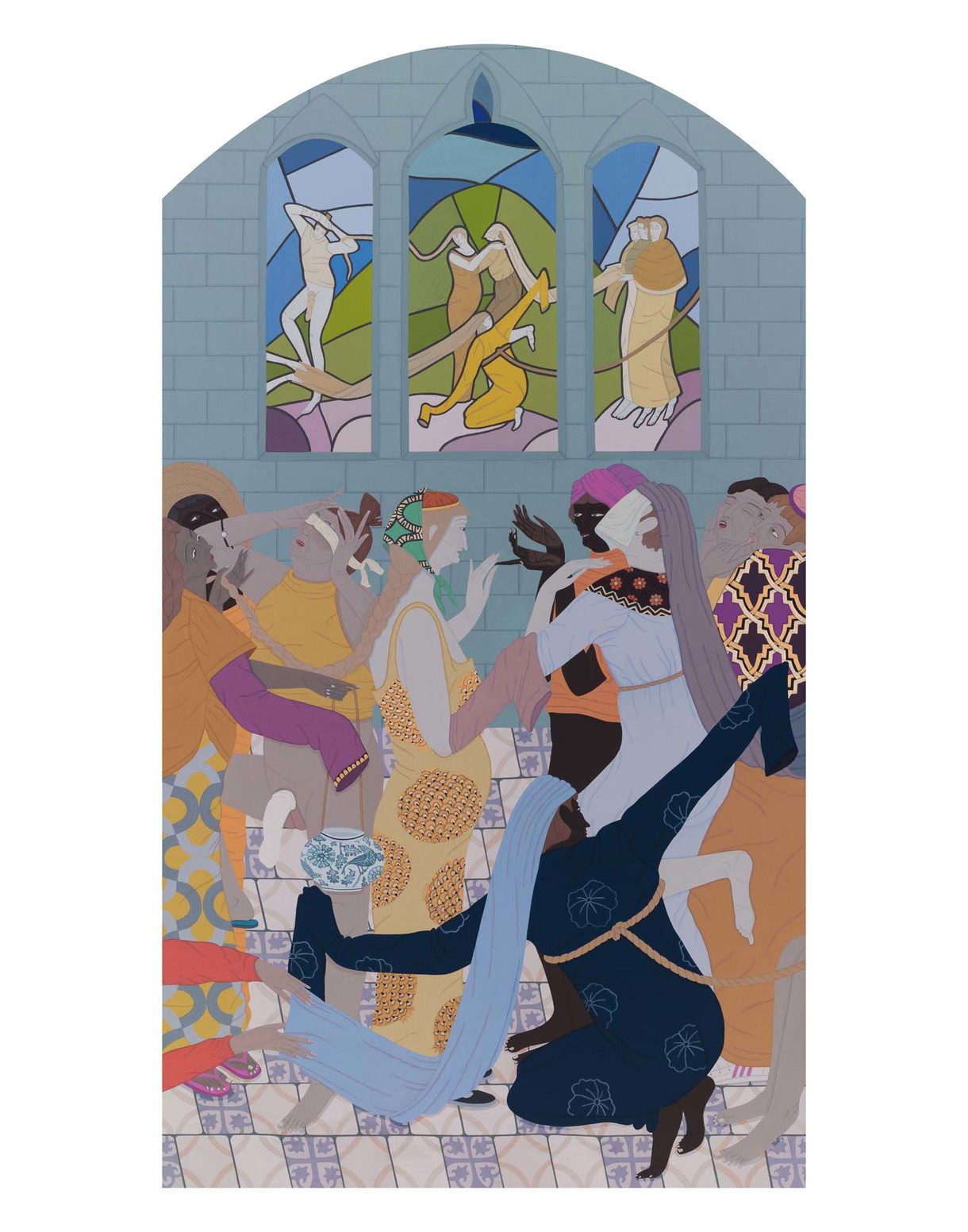

Observing Rituals

Kushana Bush is a Dunedin-based artist, whose meticulously detailed and stage-like worlds blend religious themes with secular narratives, often manifesting in ritualistic violence. Her paintings examine what spirituality, ritual and community might mean in a contemporary world. She spoke with Balamohan Shingade of ST PAUL St Gallery in February

Interview

In The Studio

Paul Moorhouse: We are standing in front of a full-size cartoon for Cosmos, the new wall painting that will be installed at Christchurch Art Gallery. How does the cartoon relate to the final wall painting?

Bridget Riley: The cartoon is painted in gouache on paper, but it gives me a good idea of the full-scale image that will be recreated on the wall in Christchurch. I have also made a smaller painting in acrylic directly onto the wall here in the studio. This is complete in itself, and provides the information I need to give me confidence in the appearance of the discs when the larger image is created on the gallery wall.

Interview

Sideslip

Sydow: Tomorrow Never Knows recently opened at Gallery and the exhibition’s curator, Peter Vangioni, took the opportunity to interview UK-based sculptor Stephen Furlonger. Furlonger was a contemporary of Carl Sydow and mutual friend and fellow sculptor John Panting, both at art school in Christchurch and in London during the heady days of the mid 1960s. His path as an artist during the late 1950s and 1960s in many ways mirrored that of Sydow and Panting.

Interview

A Torch and a Light

Shannon Te Ao is an artist of Ngāti Tūwharetoa descent. In 2016 Te Ao won the Walters Prize for his works, two shoots that stretch far out (2013–14) and okea ururoatia (never say die) (2016). Working in video and other performative practices Te Ao investigates the implications of various social and linguistic modes. Assistant curator Nathan Pohio, himself a nominee for the 2016 Walters Prize, discussed working practice with Te Ao in December 2016.

Interview

Not Quite Human

Lara Strongman: The title of your new work for the Gallery is Quasi. Why did you call it that?

Ronnie van Hout: Initially it was a working title. Because the work would be outside the Gallery, on the roof, I was thinking of Quasimodo, from Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. I was coming out of a show and research around the idea of the freak, the outsider and things that are rejected—thinking about how even things that are rejected have a relationship to whatever they’ve been rejected by. And I called it Quasi, because it’s a human form that’s not quite human as well. The idea of something that resembles a human but is not quite human.